This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

During the early spring of 1980 Michael Eugene Harper, age 21, decided that he was old enough to strike out on his own. He loaded his belongings onto his motorcycle, turned his back on his parents in middle-class Nederland, and rode off to start a new life.

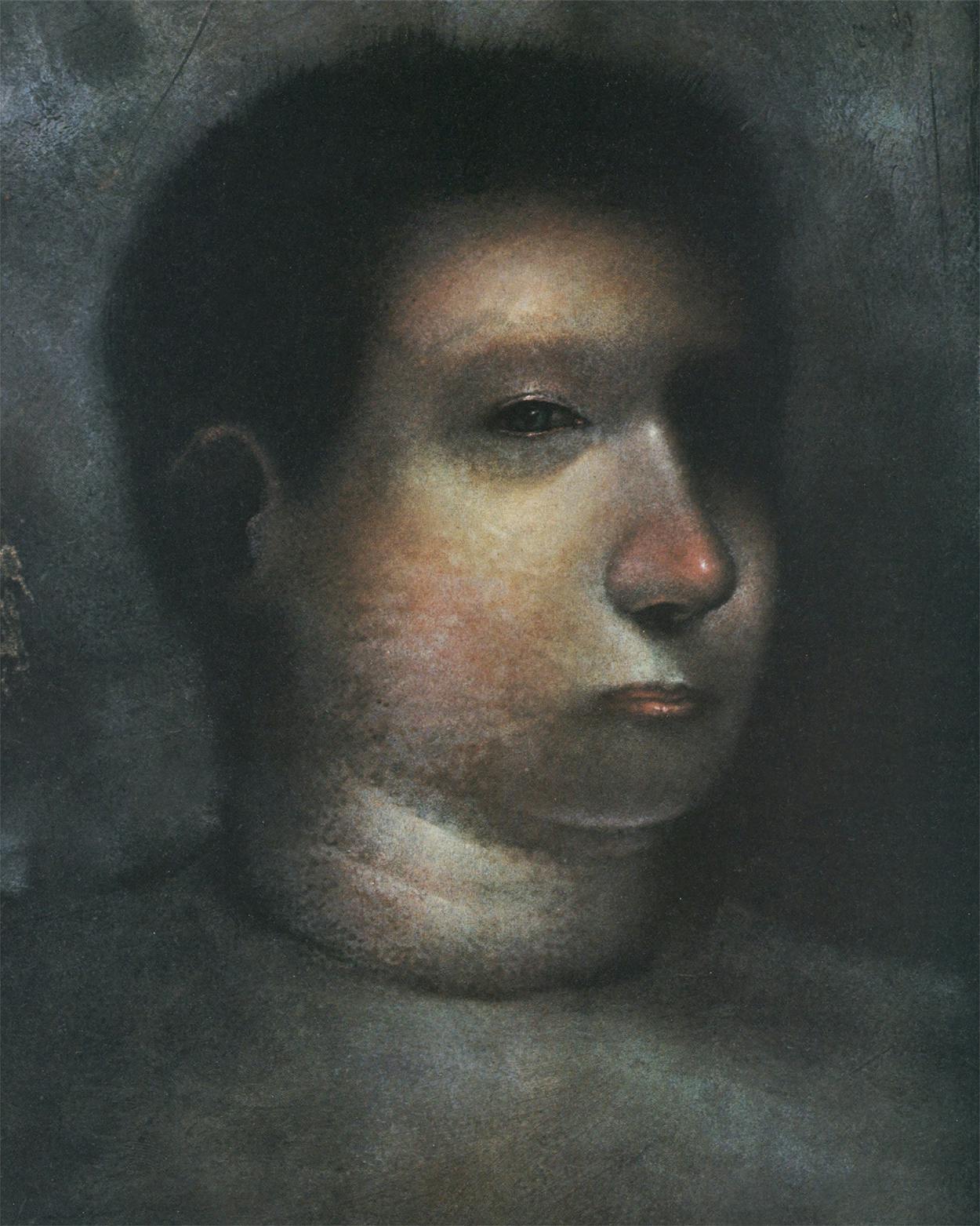

Mikey, as his family and friends called him, was a big, beefy boy with deep-set green eyes and short, curly blond hair, a cherub with peach fuzz and blue jogging shoes. He stood six feet tall and weighed 220 pounds, and his thighs were so huge that he had trouble finding jeans that fit him. Mikey’s girth was mostly muscle; he could pick up an engine block and carry it to wherever you wanted it to go. Physically, Mikey was overendowed, but mentally he was missing something. Nobody knew exactly what it was. He could remember names and dates—all sorts of erudite information—but he didn’t have whatever it takes to get along in the world. Maybe it was common sense that he lacked. He had a high school diploma he’d earned in a program for vocational students, but he was mustered out of the Army three months after he joined. He had been admitted to the state mental hospital at Rusk, but after a period of observation he was discharged. In the years since his graduation from high school, Mikey had lived with his parents and his grandparents but hadn’t been able to get along with anybody. Mikey thought that by becoming independent of his parents, he could do what he had always dreamed of doing, be what he had always wanted to be.

He had packed all the gear he thought he needed onto a rack on his motorcycle. There were things that any young bachelor setting out on his own would want—clothing, cooking utensils, a radio, bedding—but then Mikey had stuffed all the gadgets that he thought he couldn’t do without into an olive-drab Army pack. One of them was a battery-powered blood pressure gauge. Mikey didn’t have high blood pressure. He carried the gauge because it stood for something important. It could save lives, which was what Mikey wanted to do. As most people do, Mikey had romantic ideas about himself.

Unfortunately, Mikey had overpacked. The bundle he tied to his motorcycle was so big that it broke the luggage rack. Less than ten miles from home, Mikey came to rest in the slums along Port Arthur’s Sabine-Neches Canal. The area had been in decline since World War II, when employees at the Gulf and Texaco refineries, the mainstream of the city’s working class, began moving north to suburbs like Nederland. From the ship channel on the south to beyond Gulfway Drive, fifteen blocks north, and from the refineries on the West Side to Ninth Avenue, fifty blocks east, Port Arthur was a ruin. Neglected and abandoned two-bedroom houses slumped shoulder to shoulder, clad alike in chipping paint and curling shingles, tatters of the past. The slums of Port Arthur were a refuge for black people trapped by bitter, lingering prejudice and for blacks and whites whose lives had been ill-spent or disfigured by misfortune. It was the kind of place where you would live if you had no place to go except the house your parents bought when you were born.

Had Mikey gone anywhere else, he would not have been tolerated. He was too boisterous and self-confident for the role ordinarily assigned to people with limitations, nor could he assume the responsibilities incumbent on adults in a competitive society. But the slums understood Mikey. He was like his surroundings.

In the slums, when you go to buy or rent a house, you don’t consider what you would like to have, but you look at what is there, what hasn’t been ruined, and what use you can still wring from it. Or you look for the right price. In the slums your house, your car, your washing machine, and, as likely as not, your spouse and the children in your care have already been abused and battered by someone else. You accept them because you can refurbish or revitalize them or because you know that they can withstand the neglect and maltreatment that your own resentment will wreak. Mikey was an appropriate fixture for the slums because, despite his shortcomings, he was cheerful and sturdy enough to endure rough handling. And perhaps most important of all, like the welfare check that comes in the mail once a month or the silver coin found beneath a rotten plank in the flooring, his companionship was free. Nobody had to earn it.

Mikey’s story tells us something about ourselves and how we take care of our own. Most of us—if we haven’t come from too privileged a world—knew someone like Mikey when we were children, before we started climbing our own ladders. Most of us have forgotten about our own Mikeys and have no idea what happened to them, just as we tend to ignore the extensive layer of society that they inhabit. We go on our way, forgetting that this other world exists.

The people who knew Mikey say that in the first months of that first summer he would park his Honda at night beneath the breezeway at the Baptist church on the city’s black West Side. He’d strap his sleeping gear onto his back, climb up the breezewav, and walk to the chapel’s roof, where he slept. The perch was cool, and it gave him a view of the refineries just to the west. Mikey suspected that saboteurs prowled the dark recesses and fence lines of the refineries, and with a set of binoculars he carried in his Army pack, he kept watch for them.

It wasn’t until August that Mikey found a regular place to stay. One night he was riding his Honda in the slums when he saw the flash of a red beacon in his rearview mirror. He looked around and saw a patrol car coming toward him from a distance and gaining speed. Mikey decided to lead a chase. Whipping and weaving through traffic, he made it to the intersection of Gulfway Drive and Ninth Avenue and noticed an abandoned hamburger stand one block farther north on Ninth. The stand was dark and deserted. Mikey doused the Honda’s lights and came to a stop behind it. The policeman pursuing him didn’t notice the maneuver and drove on by. Mikey pushed his motorcycle inside the stand to wait awhile. The place was empty, roomy, and relatively clean. Mikey stayed for the night, and then he stayed for months.

The area surrounding the hamburger stand became Mikey’s range, or his jurisdiction, as he called it. It was a terrible little turf about twenty blocks square. It ran from his redoubt at the hamburger stand one block south to Gulfway Drive, eight blocks west on Gulfway to Memorial Boulevard, then north four blocks to a place where railroad tracks passed over an intersection of storm sewer tunnels. It was an area of second-rate commerce, frequented by the honest and not-so-honest poor, a junction where thieves, prostitutes, bikers, and dope dealers met night and day. It was the front porch of Port Arthur’s slums.

Every afternoon, after sleeping most of the morning, Mikey walked from the hamburger stand to Gulfway Drive. Gulfway gave Mikey sustenance. The eight blocks from Ninth Avenue to Memorial Boulevard were lined with garages, auto parts shops, mom-and-pop stores. The Port Arthur Honda shop was located between Fourth and Fifth avenues, and Gene Davis, the shop’s owner, sometimes paid Mikey to run errands and do odd jobs. Mikey survived by doing the chores that came his way from Gulfway’s merchants. On the strip between Sixth and Seventh avenues was a pawnshop where Mikey browsed for guns, badges, and other police paraphernalia. Across the street was the Village Theatre. When Mikey had money in his pocket, he’d go and watch all three features.

Late every evening, after everyone had gone home, Mikey patrolled the length of Gulfway from Ninth to Memorial. Dressed like a security guard, he had a wooden nightstick and a walkie-talkie strapped to his belt, and he carried a long, six-battery flashlight. He checked the front doors, back doors, and windows of businesses on the strip. If a door was unlocked or if a window was open even a crack, if drapes on a showroom were drawn or if he heard voices in the alley, Mikey called the police from one of the pay phones on Gulfway. He usually reported his observations as signs of a burglary in progress. Then he would stick around until the police checked the premises and thanked him, with increasing annoyance. Then Mikey would continue on down the street until he came to Memorial, where he’d turn and go one block north to the Tonga Club, a sprawling, low-roofed topless bar.

One day that summer, temptation got the best of Mikey. He tried to shoplift a $2 cigarette lighter from a West Side grocery and ended up in a cell at the city jail. Late that night he heard the door of another cell clang shut. Mikey peeked out the window in the door of his cell, and from across the hall a tall, slender brunette smiled back. Mikey’s jailmate was Lisa Jackson, a young dancer at the Tonga and the sort of woman who believed that turquoise jewelry and tattoos made her pretty. She had dropped out of school to go to Michigan “because that’s the way the truck driver was headed,” then returned home briefly before traveling on the carnival circuit, where with the aid of strobe lights and mechanical rigging, she had transformed herself each night into the Gorilla Girl. Lisa was in jail for drunkenness. Whenever she came to the window of her cell, a clowning Mikey greeted her through the glass of the opposite cell. Their flirtation lasted only a few hours, but after Mikey was released, he began showing up at the Tonga to court her.

The regulars at the Tonga—mostly bikers, dope dealers, and refinery workers—treated Mikey as a buffoon. With his peach fuzz and guard getup, he looked the part. Lisa was an old hand at keeping unwanted suitors at bay, and she had qualms about encouraging Mikey, who would never buy drinks for her anyway. But Mikey wanted to do more than court Lisa. He wanted to save her from the dangers of her world, and Lisa couldn’t stop him from trying. When she left the club at closing time each night, Mikey followed her to the corner of Gulfway and Memorial, two blocks from her home in the slums. From the corner he watched to make sure that she entered her house unharmed. Then he’d have a late-night burger at a cafe, or, if he was penniless, go straight east on Gulfway, checking doors and windows as he went. At the corner of Ninth Avenue he turned north and walked to St. Mary Hospital, across the street from the hamburger stand. Mikey had taken it upon himself to patrol the hospital parking lot, keeping an eye out for the rapists and muggers that he imagined lurked there. Not until sunup did Mikey lie down on his bedroll at the hamburger stand.

After finishing his rounds one afternoon, Mikey decided to scout the stretch of Gulfway that lay west of Memorial Boulevard, the salt-and-pepper slum where Lisa Jackson lived. As Mikey walked the street, he spotted a yellow frame house in a state of neglect just across from Lisa’s place. Sheets of plywood had been nailed over the windows. He went to the door and knocked. No one answered. He turned the doorknob, then shoved on the door. It gave way. Mikey stepped inside. There was no furniture there, no sign of habitation. Mikey decided to move in. To guard against the discovery of his presence by landlord’s agents and casual passersby, he left his Honda—which rarely ran anymore—with relatives in Nederland, then stacked his belongings and laid out his bedroll in the attic of the abandoned house. Mikey called the place the Penthouse.

Now a neighbor, Mikey began making afternoon calls on Lisa, who lived with her grandparents. Sometimes she agreed to talk to him, if only because he was someone close to her own age. “My grandparents didn’t like him,” she recalls. “They thought he was weird.” But Lisa’s opinion of Mikey softened during those months. She says he didn’t brag about guns he’d owned or lie to her about imaginary feats of heroism or make sexually leading comments. He treated her like a lady, never cursing in her presence, never berating her for the life she led. “Mikey told me I was wild,” Lisa says, “but he didn’t preach or anything. He said he wanted to protect me.” In exchange for the politeness and self-effacing attention Mikey showed her, Lisa sometimes took meals to his place, and once or twice she invited him to her house for supper.

Lisa didn’t know it, but Mikey spent most of his early-morning hours at home—watching her. He didn’t patrol the parking lot at St. Mary Hospital as much anymore. Instead, when he came home from the Tonga, he climbed into the Penthouse and focused his binoculars on the house across the street. He had been living in the Penthouse for several weeks when Lisa came home from work one fall night, spent a few minutes in her house, and then headed east on foot for a convenience store just across Memorial. Mikey saw her leave and crawled down from his lookout to follow her. Lisa heard his footsteps as he crossed Gulfway, and she looked behind her. She saw Mikey but did not acknowledge him.

“Hey, Lisa, stop!” Mikey hollered. “Lisa, it’s me—Mikey.” Lisa ignored him. “Lisa, you’ve been drinking,” he continued. She kept walking, a little stagger in her step. “How much have you had to drink?” Mikey shouted. Lisa stopped, turned in her tracks, and told Mikey that she’d had plenty enough to drink, thank you, and that she wanted to be left alone.

“You’re drunk, and you shouldn’t be out here,” Mikey said threateningly. Lisa said nothing. “I can arrest you for public intoxication,” Mikey said, snatching a pair of handcuffs from his belt.

Lisa saw the handcuffs and didn’t know whether Mikey was kidding or not. She turned and ran as fast as she could until Mikey was off her trail.

People with limitations raise conflicting emotions in us—honest compassion and unsettling contempt. Their incompetence, whatever its extent or cause, excites our sense of survival, for we are a people who prize self-reliance and despise dependency. We have resolved that paradox by removing the needy from us. Big institutions care for our feeble, insane, and severely handicapped; blind men no longer sell pencils on sidewalks. The weak and impaired are no longer much in our working lives, and we do not invite them into our leisure time. They couldn’t cope, we say. And we are right; if they were always with us, we’d have to slow our pace to help them along. Our virtue is also our vice—we are so industrious and ambitious that we are always scaling new heights, leaving the less fit behind.

Outsiders who need help are most often thrown upon the mercy of other outsiders—people on the periphery, those who are least able to give help. In Mikey’s case, the person who offered help was Artie Hebert, a habitué of the Honda shop and a resident of Gulfway Drive.

Artie, 38 years old, was a lean, nervous redhead whose slinky polyester shirts seemed always too long and whose jeans seemed always too short. His face was rough and ready and came to a sharp point at the chin. When Artie smiled, you could see the decay of his teeth. Though he did not always look or act the part, he was a veteran of Port Arthur’s streets, a savant of its slums. He had been on felony probation while still a teenager, and during the sixties he had worn the patch of the Bandidos motorcycle gang. He had raced stock cars and worked as an electrician, a dogcatcher, and a plumber. Like Lisa Jackson, Artie had been on the carnival circuit, only he had stayed longer and prospered for a time as the operator of a food concession. Like Mikey, Artie was an outsider to mainstream society, but for the opposite reason. Mikey’s inordinate and unreal ambitions kept him from being accepted, but Artie chose not to fit in because he had no ambition at all. Artie was a man who lived level to the ground, a man for whom life was not a ladder of events but a series of absurd moments. Mikey’s antics were a sideshow in the circus of Artie’s life.

Artie’s relationship to Mikey was acted out in the argot of motorcycle gangs. Mikey called himself Artie’s “prospect,” a pledge or apprentice. Artie called himself Mikey’s “sponsor,” or master. According to the tradition not only among bikers but also in college fraternities, military orders, and other crucibles of male brotherhood, Mikey was subject to Artie’s arbitrary control.

A few days after Artie and Mikey met in the Honda shop, Mikey’s humiliation began. He had visited his parents in Nederland, and at his mother’s insistence he had showered, shaved the peach fuzz from his face, and put on a pair of dress pants she had bought for him. When he went by the Honda shop that afternoon, he was wearing the new pants and, because it was rainy, a pair of rubber fireman’s boots that he treasured. Artie was at the shop when Mikey came in.

“Say, what are you doing wearing rubber boots?” Artie demanded. Mikey explained that it was muddy outdoors. “Don’t you know that prospects don’t wear rubber boots?” Artie teased. Mikey denied knowing any such thing.

Just to make sure Mikey learned, Artie ordered him to crawl around the perimeter of the building in the mud and rain while shouting, “Prospects don’t wear rubber boots.”

Without a murmur, Mikey went outside, lowered himself to his knees, and began crawling. The men from the Honda shop cheered him on, and Artie kept watch to see that Mikey crawled like a baby in diapers, on his hands and knees. When Mikey had completed one circuit of the building, he rose halfway to his feet—but Artie told him to get down again. Mikey made another round, then another, crawling and shouting in the rain. Only after there were holes in his pants and his knees were bloody did his sponsor relent, convinced that Mikey would remember the ad hoc dress code for prospects.

Mikey endured the hazing not only because he needed a mentor but also because he planned to use his sponsor for a front. Artie was a trusted figure among Port Arthur bikers, and Mikey wanted to be privy to their secrets. He wanted to find out who was selling drugs to girls at the Tonga and how big the drug traffic was. Artie knew those things, although he minded his own business and said little about what he knew. Mikey wanted Artie to talk. Then, Mikey figured, he could crack the drug rings and pass his information on to the police. He would be able to tell Lisa that he was the hero who had saved her from yet another peril.

By New Year’s Eve, 1980, when the Gulfway Cycles shop threw a party, Mikey was well known to bikers and the police. The shop was across the street from Mikey’s place and next door to Lisa Jackson’s house. Unlike the Honda shop, it was a hangout for bikers who Mikey believed were dealing in dope. Mikey had alienated the shop’s owners, who were friends of Artie’s, with his inane talk and constant loitering. He had also been seen flagging down police cars on Gulfway and sitting on the curb, talking too long with the cops. The information Mikey gave the police wasn’t worth much to them, patrolman Milton Levy recalls, but it had been enough to rouse the ill will of dope dealers and their friends. Levy had been called to Gulfway Cycles one afternoon a few weeks before the party to rescue Mikey after some Bandidos had made threats. Levy told Mikey then that he should stay away from bikers and the Gulfway shop, but Mikey kept playing cat-and-mouse games. He hadn’t been invited to the New Year’s party, but he showed up that afternoon, and hung around, saying that he had come only to see his sponsor, Artie Hebert. Bikers in the crowd taunted Mikey to take a drink, but he steadfastly refused, even after a ninety-pound woman downed a glass of whiskey as a challenge. That’s when Artie stepped in.

“Now, Mikey, don’t you shame your sponsor,” artie teased. “If that little girl can drink that much whiskey, so can you.”

“I know you’re my sponsor, but you know I don’t drink,” Mikey protested.

“Are you going to make me the laughingstock of all these people?” Artie insisted, gesturing toward the throng.

Mikey took the drink and then, goaded by his sponsor and the onlookers, he took another and another. Before long he turned silly and smart-alecky. When he began to make wisecracks about a couple of Bandidos, Artie hauled him over to a doorway at the side of the shop and away from the crowd. “Now, prospect,” Artie admonished, “I want you to sit down right here, and I don’t want you to move unless I tell you to.” Mikey dropped to the concrete, chastised and limp.

The side door, about six feet wide, was used to bring motorcycles into the shop for repair. At closing time each day, someone from the shop went outside to ride the motorcycles into the garage for safekeeping. That New Year’s Eve the task fell to Louis Marceaux, one of the shop’s owners. He mounted a bike and rode it to the doorway, where Mikey’s outstretched legs were blocking the entrance. Louis ordered Mikey to move.

“My sponsor told me to sit right here, and I ain’t moving until he says,” Mikey blurted out.

Louis edged forward on the bike until its front wheel touched Mikey’s thigh. Mikey refused to budge. Louis gunned the bike a little, and it moved forward, pushing Mikey’s legs in front of it. But Mikey wouldn’t get up. “I’m warning you, I’ll ride right over you,” Louis repeated. Mikey wouldn’t move.

Louis twisted the accelerator grip, harder this time. The motorcycle, which weighed more than five hundred pounds, rolled over Mikey’s thighs. Mikey winced and bent forward a little but did not move. Artie, who had heard the commotion, went to the door and told Mikey to get up. Mikey tried to stand, but he couldn’t—he was drunk or injured or both. Artie and another celebrant stretched Mikey’s arms over their shoulders and, like two men helping a player off the gridiron, carried Mikey to his house. They laid him in a corner of a downstairs room, where he vomited and then passed out.

Mikey recovered and returned to his old haunt, where he was hazed and taunted as before. To keep him out of work’s way, the Honda shop mechanics painted a white line across the garage floor and told him not to cross it. But he did. They then built a cage from a motorcycle crate, placed a sturdy box inside as a chair, and told Mikey to take a seat. He did. The mechanics tied the crate’s latticework door shut. Mikey didn’t complain. He enjoyed being their prisoner. During the weeks that the cage was in the shop, Mikey sometimes got in on his own, without having to be told that he belonged there.

Early one afternoon on a day when Mikey had made a nuisance of himself, Artie and the Honda mechanics decided to give him a little scare. “We kept telling him that he was so dumb, he ought to be punished for it,” Artie recalls. Mikey said that he agreed with their evaluation. They made a noose and dropped it around Mikey’s neck. He didn’t object. Artie and the mechanics led Mikey to a tree on the shop’s unpaved parking lot. One of them threw the free end of the rope over a stout branch, and the others hoisted Mikey upward. “He didn’t fight at all,” Artie says, “until we got him to where he couldn’t touch the ground with his tiptoes. Then he began to kick a little.” When Mikey’s lips began turning blue, his tormentors cut the rope. Mikey got up from the ground, loosened the noose that still encircled his neck, and broke into a smile.

By the late spring of 1981 Artie and the men at the Honda shop were tiring of Mikey’s childishness. They lectured him about the need to bathe, they carped about the hamburgers and pocket change they had doled out to him for months, and they told him to get a job. Mikey didn’t take them seriously until Artie laid down a new rule: before he could complete his term as a prospect, Mikey would have to buy a motorcycle for his sponsor. The requirement left Mikey no choice. He had to go to work. Though they cloaked it in the guise of hazing, Artie and the Honda mechanics had decided to form a new relationship with Mikey. They were going to help him grow up.

They found one dishwashing job for Mikey, then another, at eateries on Gulfway. Mikey didn’t last a month at either place. They got him a third job as a janitor at a discount house just east of Ninth Avenue. He decided to keep the job when he discovered that by hiding in a rest room at closing time, he could stay in the store all night. The discount house had running water, heat, and air conditioning—conveniences Mikey didn’t have in the Penthouse. One night he prepared a junk food buffet on the manager’s desk, then took a nap on the manager’s couch. When he awoke, the manager was standing over him. Mikey was fired on the spot.

Late that summer artie found Mikey the kind of job he’d always wanted. Artie’s wife, Karleen, worked at the Port Arthur Plumbing Company, which had been burglarized by a thief who took items valuable only to a plumber. Karleen thought the burglar might return, perhaps when he started a new plumbing project, and she hired Mikey as a watchman. To make his nights more comfortable, she and Artie provided Mikey with a bed, a coffeepot, and a portable television set. Karleen paid him $5 a night plus supper.

Every evening for more than a month Artie drove Mikey to work and let him into the shop. As Artie was leaving one night, he noticed an American Cancer Society donation can on the customer service counter. It contained a $1 bill and some change. The following morning Karleen telephoned Artie from the shop. Mikey was still there, loitering and getting in the way. She wanted Artie to make Mikey leave. “By the way,” Karleen asked, “wasn’t there a dollar in the Cancer Society can last night?” The dollar had disappeared.

Artie was furious. He had thought better of Mikey than that, and he thought that Mikey owed him more respect. He drove to the plumbing shop, pulled a twelve-gauge shotgun from behind the seat of his pickup, and went inside. Mikey, who was standing by the counter near the front door, began backing up. Artie backed him all the way into the workshop at the rear of the building.

“Mikey, is it worth a dollar?” artie shouted.

“What are you talking about?” Mikey whined.

Artie swung the shotgun butt at Mikey’s face. It struck him on the chin, knocking him backward and opening a gash that took weeks to heal.

Mikey’s career as a watchman and prospect was over.

At that point Mikey’s chances of finding a place where he belonged looked bleak. Knocked loose from Artie and his job at the plumbing shop, he spent most of his time patrolling the city’s storm sewers. Wearing his fireman’s boots and carrying his policeman’s flashlight, he entered the tunnels every night at a junction beneath Memorial and walked for hours, shooting at rats with his .22 rifle and poking around in the detritus, looking for stolen goods and contraband.

Mikey wasn’t entirely dejected by the turn his life had taken, nor had he failed to learn from his troubles. He had learned, for example, that he got along much better when he had a job. He soon found a new one—guarding the parking lot at the Tonga.

A few days after Mikey was hired, Lisa Jackson invited him to accompany her on a day trip to Louisiana. Mikey thought he was in heaven. He was a guard, and maybe he had a girlfriend too. The two had been on the road for less than half an hour, Lisa says, when Mikey propositioned her. She refused. Almost as if to make a joke of his discomfort, Mikey reached for the straight razor that Lisa carried in her car for self-protection. He held the blade menacingly between his fingers. Lisa says, “He told me that if I didn’t sleep with him, he’d cut me.” She decided that she’d had enough of Mikey’s jokes. She halted the car, took the razor from him, gave him a scolding, and told him to get out. He hitchhiked home.

Mikey kept working at the Tonga, but the job wasn’t the same after that. Lisa was cool to him. She discouraged his afternoon visits, and perhaps because he knew that there was nothing to gain, he quit following her home at night. When the Tonga closed, he’d prowl the storm sewers, then surface at an all-night convenience store on Gulfway, where he’d stand around in his guard getup as if he were on duty there.

One night there was a serious traffic accident on Memorial right in front of the Tonga. One of the passersby who stopped to lend a hand was Glen Cory, a fireman Mikey knew from Nederland. As the wreckage was being hauled away, Mikey and Cory discussed old times, and Cory offered to rent Mikey a mother-in-law room in his house just outside the slums.

Glen Cory was a good-sized man in his early thirties, as strong and stout as Mikey. He and his wife, Annette, were evangelical Christians who felt it was their duty to be patient and compassionate. On his days off, Glen took Mikey sailing, counseled him on the importance of orderly personal habits, and tried to convince him that guns and badges don’t make a man a hero. Annette sometimes let Mikey baby-sit for the couple’s preschool twins, but only for five or ten minutes at a time. “Mikey behaved about like the kids,” Glen says. Mikey played with his paraphernalia in his room and once let his .38 pistol discharge inside the house. Glen says he had to keep a close eye on Mikey’s room, where the water heater was located, “because the way he kept the place would have created a fire hazard.”

In many ways Mikey had found the ideal place to live. The Corys liked him. They were good people, eager to help; yet, regardless of their concern, the experience of living with them spoke less directly to Mikey than his time with Artie had. Mikey needed a world where there were heroes and villains, where the distinctions were black and white. He needed extremes, and, therefore, he was drawn to extreme situations. Not long after he moved in with the Corys, Mikey took a job as a bouncer at the Mark VI Showcase, Port Arthur’s biggest, most dangerous black nightclub. Most people who knew Mikey said he was as good as dead.

The Mark VI was located just north of Port Arthur’s decrepit downtown, where even at noon, drivers handed money through car windows to characters whose offices were the sidewalks, and women in tank tops waved at strangers and rode away with them in their cars. The Mark VI was housed in a big, flat-roofed, windowless building. Each time dance styles changed radically or violence inside the building drove patrons away, the club changed its name and sometimes its management and decor as well. The owner of the property, Johnny Hargrove, maintained that only three murders took place there; policemen put the number at six. The place was so notorious that when it reopened as the Mark VI, security companies and off-duty patrolmen refused to hire on for guard duty. Mikey’s acquaintances at the police department warned him not to take the job, but he was unimpressed.

Inside the Mark VI there were nearly a hundred blipping strobe lights on the ceiling, and four spinning glass balls reflected beams of red, blue, yellow, and green onto the peach-colored walls and the crowds of dancing customers below. The club’s sound system was potent enough to make clothing flutter and costly enough that foiling burglars became a preoccupation of the management. More than a thousand people packed the place on weekend nights.

His first night on the job, Mikey showed up with a pistol, but the club’s owner wouldn’t let him carry it. Mikey walked a beat of the rest rooms to make sure that nobody sneaked off to smoke a joint, and he surveilled the disco, hoping to spot patrons who had brought liquor into the club in violation of the law. When he collared an offender, he called the police. “Mikey wanted to send people to prison for bringing in a half-pint bottle,” Hargrove said. His boyish overreactions earned him the nicknames “Bulldog” and “Deputy Dog.” The other guards, two black women, grew tired of apologizing for Mikey’s antics to their friends in the community. A lot of people said Mikey brought too much enthusiasm to his job.

But Mikey also brought an almost contagious sense of mission to the block. He believed that keeping order was important, and he persisted. He stood just outside the Mark VI every night, demanding identification from patrons who looked too young to drink, and when it wasn’t forthcoming, he stood in the doorway, barring their entry. The police couldn’t keep winos and dope dealers off the grounds, but Mikey learned to persuade them to move across the street. When fights broke out, Mikey wouldn’t step in on his own, but he developed a knack for dispersing quarreling patrons before knives flashed or fists flew. Mikey was able to keep order, perhaps because he had something going for him that was rare on Seventh Street. He was naive enough to believe that there could be peace there. His attitude surprised people and won their sympathy and cooperation. Not many men, especially white men, would have risked themselves to do what Mikey did. He was still in good standing at the Mark VI and on the block when in late 1981, following an incident in which a customer was killed, the club at Seventh and San Antonio again closed its doors.

Mikey seemed to have that innocent kind of luck that would allow him to survive in spite of himself. Before long, he was at work again, this time as a helper at Serv-Tech Specialists, a hydroblasting firm. Hydroblasting is an industrial cleaning process that uses bigger, more complex versions of the equipment found in coin-operated car washes. Typically, three men work on a rig: one at a pump, one at a foot control, and one at a lance that is like a car-wash wand. To start or stop blasting, the lance operator signals the man at the foot control. By depressing a pedal, the control operator starts the flow of water and keeps it going. By releasing his foot, he stops it. For a few seconds after the flow is halted, water spews out a relief valve at the side of the control mechanism, sometimes with enough force to do damage. Hydroblasting requires cooperation, stamina, and, most of all, alert caution. Car-wash wands deliver about a thousand pounds of pressure, enough to break the skin at most, but the stream from a hydroblasting rig can cut a man in half.

Mikey had been working for Serv-Tech about two months when, on the afternoon of Wednesday, February 10, 1982, he showed up for work at a Mobil Chemical plant in Beaumont, wearing his rubber fireman’s boots. Serv-Tech was clearing the lines of a coke reactor unit at the refinery. The three men in Mikey’s crew worked through the evening and all that night, which was clear and cold. They were still on the job at sunup, about six o’clock, when Mikey, untired despite the long hours, climbed onto a platform to take his turn at the foot control. He had been holding down the control pedal with his right foot for about half an hour and had shifted to a comfortable standing position, when the lance operator, working above him, signaled him to stop the flow. Mikey released his right foot from the control pedal, and a blast of water from the relief valve struck his left foot just below the ankle. He dropped limply to the platform, legs outstretched in front of him. He was in pain. He yelled for help. The lance operator climbed down to aid him, took one look at Mikey’s foot, and fainted. Mikey’s foot was shot full of water. It and the fireman’s boot had ballooned to five times their normal size.

Later, when he filed a lawsuit in Beaumont’s 172nd District Court, there was controversy over whether the relief valve should have been, or was, connected to a baffle, but even Mikey admitted that he had placed his foot in a spot where he knew it didn’t belong.

The doctors couldn’t save Mikey’s foot. His left leg was amputated about six inches below the knee. When Mikey left Baptist Hospital in Beaumont about a month after the accident, he did not return to the Cory house. Instead, he spent the next months recuperating at his parents’ home. He was fitted with a flesh-colored fiberglass prosthesis, and he learned to walk with it. He also collected a workers’ compensation award for $17,000. In July he returned to the streets of Port Arthur, cheerful and flush.

Mikey was rich, or at least he felt like he was. He didn’t have to endure other people’s abuse anymore, and he didn’t have to listen to their advice either. He could indulge his fantasies and did. He stopped at Lisa Jackson’s house to tell her that his lawsuit would soon make him a millionaire in need of a wife, but she ignored his suggestion. He bought a new Ford Escort, fire-engine red, and equipped it with a police scanner and an amber flashing light. He bought the authoritarian paraphernalia he had eyed for so long: a set of shackles, a .357-caliber pistol, a riot gun, and two semiautomatic rifles. He even held himself out as a bounty hunter, canvassing the area’s bail bondsmen for clients. There was an error on his business card—it read, “Bell Retriever,” not “Bail Retriever”—but Mikey was undaunted. He made rounds with the card anyway.

Mikey’s money didn’t last long. By mid-August his savings had dwindled to $320. To make ends meet, instead of going back to Glen Cory’s house (the Corys had a new tenant) he moved into the home of Lex Faulk, a former bouncer at the Tonga Club. Faulk, age 38, was a blue-eyed, gruff-voiced, potbellied man who, like Mikey, had a handicap. Polio had afflicted Faulk in childhood, and he wore a steel brace on his right leg and a thick-soled shoe underneath. He swayed from side to side when he walked, but his chest was broad and his arms were thick and tough, and he wasn’t afraid to brag that he had never hit a man who didn’t fall. As a biker—Faulk rode a three-wheeled rig with an outlaw club from Houston—and as a bouncer, he had struck more than his share of men.

He lived in a two-story house on Twenty-sixth Street near the corner of Gulfway and Memorial. His son, Jimmy, a high school junior, lived in a travel trailer in the back yard. Nancy Denton, a svelte 28-year-old blonde who had been a waitress at the Tonga, shared a downstairs bedroom with a pet python. Other people sometimes lived at Lex’s house too, usually upstairs: topless dancers, bartenders, bouncers, and an occasional biker.

Like Artie before him, Lex took a paternal interest in Mikey. He bought tires for Mikey’s car, told him to bathe, and made him do household chores. When he discovered that Mikey was putting oil in the Escort’s radiator, Lex tried to teach him the basics of automotive upkeep. Lex and Nancy provided Mikey with meals, loaned him spending money, and let him sleep upstairs. In effect, they adopted him, partly out of pity, partly for friendship’s sake, and partly because they believed that they would recoup any funds they spent to support him. Mikey’s lawsuit was in the hands of a well-known attorney, and besides that, when Nancy had worked as a barmaid, she had met an insurance investigator who told her that Mikey’s claim was sure to pay a bundle.

If Lex and Nancy were like parents to Mikey, Jimmy was like a brother. The two young men spent whole nights together, cruising in Mikey’s car. A couple of times they drove across the border to Cameron or Lake Charles, and on Christmas Day, 1982, they ran down to Galveston just for the ride. Mikey liked to patrol parking lots and to go target shooting on Pleasure Island, but Jimmy grew reluctant after Mikey rushed to the site of a downtown burglary one summer night, only to be mistaken for the driver of a getaway car. “When that cop poked that shotgun through the window on my side of the car,” Jimmy says, “I knew I wasn’t going patrolling with Mikey anymore.” The next spring the Escort was searched, and Mikey was arrested for carrying a dagger. After that, Jimmy refused to get in the car when Mikey was armed.

In June 1983 Lex began preparations to open a club called the Pink Panther at 440 Procter, an address that had been home to jewelry stores for more than fifty years but during the past decade had harbored several bars. The Moulin Rouge, the Blue Dolphine, and the Torch Lounge had led brief, unhappy lives there. The block wasn’t a busy one. The Pink Panther’s neighbors were a newsstand, a defunct liquor store, a defunct loan company, a Goodwill outpost, and a shop whose only sign read, “Jesus the Cornerstone.” The only strong survivors on the street were a seamen’s bar and a Walgreen’s drugstore.

When Lex opened the Pink Panther in July, Mikey went to work for him. Each night Mikey came in shortly before closing time to earn $5 for sweeping the club. Sometimes he also sold his services as an unchartered taxi driver; for $5 he would drive people home. He gave free rides to Bernadette Smith, a Pink Panther topless dancer.

Bernadette was a young woman with brown shoulder-length hair and freckled, strawberry cheeks. She looked like she belonged on the label of a raisin box, not in a topless bar. She had a quiet, childlike voice, an aura of natural innocence, a demure style of dress. She also had an estranged husband and two children. When Mikey drove Bernadette home, they sometimes stopped at all-night cafes and doughnut shops, where Bernadette would talk for hours about her marital traumas. Like Lisa Jackson, she didn’t notice that Mikey didn’t bathe as often as he should, nor was she repelled by his size, even though he had gained nearly eighty pounds—he now weighed about three hundred pounds. She insists that Mikey treated her like a lady. In his expansive moods, he told her that someday soon, when his lawsuit made him rich, he wanted to send her on a trip around the world. Before the trip ended, he promised, he would fly to Paris or Las Vegas or Miami to meet her for breakfast. Bernadette was entertained by Mikey’s fantasies of wealth, but she says that she never looked beyond the immediate friendship that bound them, a friendship as public as a coffee-shop table.

Early in August Mikey told Bernadette and Lex and everyone else that his attorneys had rejected a $1 million out-of-court settlement of his suit. He said they were going to hold out for $8 million. Most of Mikey’s friends didn’t believe him, but some decided to protect their interests anyway. Lex was one of them. He drew up—and Mikey signed—a promissory note for $6100, which was supposed to cover the expenses that had come Faulk’s way during the year that Mikey had been in his keep.

On the afternoon of Friday, September 2, Mikey stopped at the Honda shop to ask for a favor that had become routine over the past months. The shoe at the base of his prosthesis had loosened, and its foot had turned askew. Mikey had never bought the tool—a metric hex wrench—needed to tighten it. After one of the mechanics had done the job, Mikey told his old friends that a settlement of his suit was in the offing. The settlement, he said, would give him nearly $3 million in cash.

Mikey went from the Honda shop to the Pink Panther. Lex sent him back out to buy soft drinks, and after delivering them, Mikey left again. He returned about closing time to sweep the club and drive Bernadette home. As he drove down a divided highway, a car approached at high speed, heading east in the westbound lane. The car came to a crossover, moved to the proper side of the highway, and barreled eastward, still weaving. Mikey pulled his amber light from underneath the car seat, set its magnetic base on the roof of the Escort, wheeled around, and gave chase. The errant auto drove onto the shoulder and stopped. Mikey pulled up behind it, stepped out from under the amber flashing light, and walked to the door of the halted vehicle. Its driver was drunk, but after receiving a tongue-lashing from Mikey, he agreed to let his wife drive. Mikey returned to the Escort, proud to have abated a public danger. He felt good; he had been a hero and had helped save lives.

He drove Bernadette to an all-night diner where two dozen John Wayne portraits hung. He told her about the big settlement that was coming to him and, over an order of french fries, asked her to be his wife. She didn’t answer his proposal, but when he asked if she would let him drive her home the following night, Bernadette agreed. Mikey was bold that night. Never before had he asked her to promise him anything in the future.

After taking her home, he went to Lex’s house. Jimmy was in the kitchen of the travel trailer, still awake. Mikey was ebullient. He told Jimmy that he had a fortune coming, and not only that—he had a date the following night with Bernadette. Mikey asked him to spend the rest of the night celebrating, riding around in the Escort. Jimmy said he’d go. Mikey went up to his room. It was dark upstairs. Without switching on the lights, Mikey picked up the .357 Colt Python from his bed. The pistol was sheathed in a leather shoulder holster and was fully loaded with bullets that Mikey had modified by sawing off their rounded heads to increase their deadliness.

He yanked the gun from its holster and flipped open its revolving cylinder, exposing the bullets inside. All modern revolvers, including Mikey’s six-shot .357, have an ejector mechanism that makes unloading nearly automatic. But Mikey never used it. Like a movie cowboy, Mikey always held the gun pointed upward a little, then tapped it with his hand, causing the bullets to fall out. That night he stood over a nightstand in his darkened room, tapped the gun, and let its bullets fall. Mikey didn’t count them. Only five had fallen to the nightstand. One remained in the gun.

Mikey returned to the kitchen of the travel trailer, where Jimmy was waiting. He saw the pistol in Mikey’s hand. “Mikey, what do you want to bring that gun for?” he protested.

“Don’t worry. It’s not loaded,” Mikey assured him, raising its barrel to his temple.

Mikey pulled the trigger.

The gun snapped on an empty chamber.

“Mikey, don’t do that! People get hurt playing with . . . ,” Jimmy was saying.

But Mikey had pulled the trigger again.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Port Arthur