This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It’s been a long time since Texas had a governor it liked. The only one to retire undefeated in the last 34 years was John Connally. Bill Clements, in his comeback term, belongs in the maligned majority. His involvement in the SMU football scandal stripped him of the ability to lead at the start of his tenure. His political infirmities have left the state adrift at a time when it has to overhaul its public schools and its judiciary.

But the start of a new campaign season inevitably restores optimism: On March 13, primary election day, Texans start the process of picking Clements’ successor. Here are the strengths and weaknesses, plans and prospects of the major candidates. Maybe this time we’ll find somebody worth keeping around.

The Republicans

“American conservatives are caught in the web of their careless anti-government rhetoric,” conservative columnist George Will wrote at the beginning of the Reagan presidency. “They are partially immobilized by their uneasy consciences about government power.” Will described exactly the dilemma of Texas Republicans in the eighties. On the verge of becoming a majority, they still behave like a perennial opposition: inclined to criticize government rather than use it, even on issues as broad-based as education. This anti-government tide ran so deep that aspiring Republican politicians seldom challenged it. But the 1990 primary, with the most diverse field in the party’s history, presents Republican voters with a rare opportunity to choose between opposing views of government. A runoff between Clayton Williams and Tom Luce, for instance, would be a struggle for the soul of the Republican party.

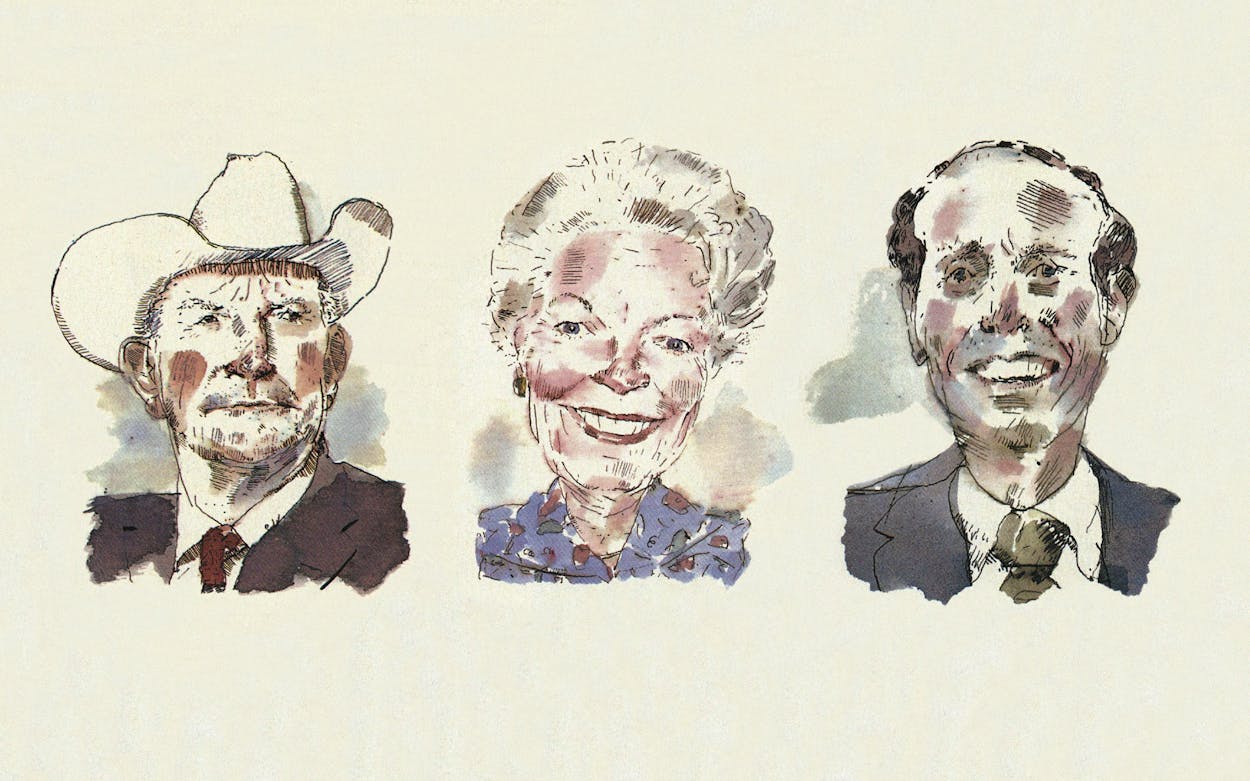

Kent Hance

47, Railroad Commissioner, Lubbock

Strength: Record

Weakness: Money, poorly defined image, no political base

Strategy: Exploit record as Reagan conservative

Prospect: Second or, more likely, third

What’s wrong with Kent Hance? He’s smart, he’s likable, he has a record as a state senator and U.S. congressman that should appeal to Republican voters—but he’s going nowhere. Hance’s weakness was evident after George W. Bush opted out of the governor’s race last summer. At the time, polls showed that the president’s son was the first choice of 26 percent of GOP voters, while Hance had around 20 percent. Ominously, Hance didn’t benefit much from Bush’s withdrawal: He remained stuck in the low 20’s while Bush’s supporters drifted into the undecided column. In retrospect, Hance should have gone on TV to woo the undecideds; instead, Clayton Williams seized the initiative. Now Hance is locked in a battle with Tom Luce to see who will face Williams in a runoff.

Missed opportunities are nothing new for Hance. He might well be governor today had he remained a Democrat and challenged Mark White in 1986. He has run statewide in each of the last three elections—for U.S. senator as a Democrat in 1984, for governor as a Republican in 1986, and, in his only victory, for railroad commissioner in 1988. Yet Hance remains a cipher to the electorate. He has run such undistinguished races that voters still have little sense of what he stands for, what he has achieved, or even who he is. Hance has a history of late-closing demagogic one-issue campaigns (opposing illegal immigration in 1984, fighting OPEC in 1988) that gain him momentary publicity but leave no lasting impression except opportunism.

Hance’s strategic solution to his lack of a clear image has been to court the ideological right as a political base. A moderate conservative for most of his career, he has the strictest anti-abortion, anti-tax positions in the race. To turn these positions into votes, he needs high-impact TV spots based on his record—perhaps his sponsorship of Ronald Reagan’s income-tax cut in Congress or his anti-OPEC crusade. But Hance doesn’t have the personal wealth of Clayton Williams or the big-money backers of Tom Luce to guarantee funding for an extended media campaign. With just $1 million on hand, he must raise another million or two—no easy chore in these times. A slip in the polls could destroy his viability with donors and force him into another late-closing demagogic one-issue campaign.

Tom Luce

49, Attorney, Dallas

Strength: Dallas base, GOP establishment connections

Weakness: Name ID, GOP establishment connections

Strategy: Win big in Dallas County

Prospect: Well positioned to make the runoff

In a party that is conservative, anti-government, and increasingly populist, Tom Luce is running as a nonideological, interventionist, establishment candidate. A Democratic consultant says that Luce has “targeted the smart vote”—something no successful gubernatorial candidate has done since John Connally. Luce’s tactics are not as daring as they might seem. The inability of Kent Hance and Jack Rains to attract the former supporters of George W. Bush indicates that a constituency is out there for the right person. Why not Luce, a name partner of one of the state’s big law firms, whose most prominent personal client is H. Ross Perot?

Because Luce entered the race late and had virtually no name ID, he had to get on television quickly and purposefully. Fortunately for him, money for a media campaign is not a problem: He has the backing of longtime Perot colleague Mort Meyerson, wealthy oilmen Ray Hunt and Peter O’Donnell, and investor Richard Rainwater. His initial TV venture wasn’t a play-safe get-to-know-me spot but a high-risk straddle-the-fence approach to abortion. Luce said that he was personally opposed to abortion but didn’t feel that government should interfere. The gambit worked. His stand alienated the extremes—right-to-lifers (who weren’t in his camp anyway) and staunch feminists (who vote mostly Democratic)—but appealed to the constituency Luce is trying to reach, the middle majority that has emerged after the Supreme Court’s Webster decision.

The continuing problem for Tom Luce will be how to reach and mobilize his establishment constituency. He is making the rounds of downtown office buildings in the big cities, a likely habitat of potential Luce voters, but the day when Republican primaries can be won by personal contact and word of mouth are long gone. TV is the name of the game. Luce, however, is the hardest kind of candidate to sell on a mass medium—someone to look up to, not someone to feel empathy with. To beat Hance for second place, he will require a large margin in Dallas and the young-professional vote from Houston and San Antonio. If he can reach a runoff, his race against Clayton Williams would divide the party into its BMW and pickup-truck wings.

Jack Rains

52, Former Secretary of State, Houston

Strength: Potential Houston base, skill in debate

Weakness: Money, name ID, antagonistic image, media hostility

Strategy: Sweep Houston

Prospect: Pray for a miracle

Almost everybody counts Rains out. Although he started running for governor three years ago, when Bill Clements made him Secretary of State, his confrontational style kept him from exploiting the potential of his office. He is the most articulate and knowledgeable Republican in a debate, but he doesn’t have the knack, so essential in politics today, of leaving people with a warm feeling.

As Secretary of State, Rains was in a position to curry favor with Republican legislators who could help him in their districts. Instead, he bullied them. In 1987, after Clements yielded to pressure and dropped his opposition to a tax increase, Rains buttonholed Republican lawmakers and tried to undermine the deal his boss had made. Not surprisingly, he found himself excluded from Clements’ inner circle. The most partisan of the Republican candidates, Rains would propose kamikaze strategies to outnumbered Republican legislators, accompanied by comments like “Pull the pin and roll it under the Democrats’ chair and let it explode.”

Rains had planned to win the nomination by combining Houston votes with a statewide Aggie network, assembled through chicken-circuit appearances before local alumni groups. But disaster struck with the emergence of Clayton Williams, who had a superior claim to Aggie loyalties—the campus home of the Association of Former Students is named the Clayton W. Williams, Jr. Alumni Center. Rains also hoped to make himself the state’s chief spokesman for economic development, but that didn’t work either. Finally, Rains tried to ride the wave of reaction to the Supreme Court’s abortion decision by opposing any further restrictions, but Luce outshined him by taking a similar stand on television. Meanwhile, Rains got caught making a contribution to a right-to-life group, causing Hance to label him “Jack the Flipper.” About the only option Rains has left is to concentrate his media campaign in the Houston market and hope that a root-for-the-home-team appeal can see him through.

Clayton Williams

58, Businessman, Midland

Strength: Money, image as archetypal Texan, Aggie network

Weakness: Knowledge of issues and government, possible gender gap

Strategy: Avoid gaffes, duck debates, spend whatever it takes to win

Prospect: The betting favorite

The remarkable rise of Clayton Williams testifies once again to the enormous power of television—and money—in politics. In one round of commercials he transformed himself from a long-shot challenger to the GOP frontrunner. Even strategists for Williams’ rivals concede that he has already locked up a spot in the runoff.

Pros in both parties say that Williams’ TV spots are the best ever to appear in a Texas governor’s race. Here’s why they were so effective: (1) Quality. Williams put up the bucks for good lighting, good cinematography, and film instead of videotape to provide realism. (2) The right issue. The drug problem pushed Republican voters’ buttons on education, family, crime, and race. (3) Texas imagery. The reference to teaching prisoners “the joy of bustin’ rocks” was pure genius. (4) Efficiency. Williams’ early start gave him a monopoly on voters’ attention. Instead of needing one set of commercials to build awareness and another to build support, he achieved both objectives in a single media campaign.

Williams has become what every candidate aspires to be: a personality figure. He has severely damaged the strategies of his three rivals, winning rural voters from Kent Hance, the Aggie network from Jack Rains, and undecided former supporters of George W. Bush before Tom Luce could compete for them. But he is not invulnerable. Williams knows next to nothing about state government. He is susceptible to gaffes. In a meeting with Bill Clements he asked if being governor was a full-time job and didn’t seem pleased when Clements responded that it was. In a runoff his voters are not as likely to show up as Luce’s or Hance’s. His drawbacks notwithstanding, Williams is the kind of candidate who wins elections in this state: an outsider, a nonpolitician, a rough-hewn real Texan.

The Democrats

There’s only one question in the Democratic primary: Can anyone beat Ann Richards? There’s only one reasonable answer: No. But reason doesn’t necessarily prevail in politics, especially when money is on the other side. With Jim Mattox certain to outspend Richards and Mark White likely to, the primary will be a case study of the power—and limitations—of money in politics.

Jim Mattox

46, Attorney General, Dallas

Strength: Money, record, toughness, organization

Weakness: Reputation

Strategy: Soften his image, outspend his rivals, contrast his record with theirs

Prospect: A dogfight with Mark White for second place

Can money and TV do for Jim Mattox what they have done for Clayton Williams? It is hard to believe that the answer is yes. Williams needed only to forge an image for himself; Mattox has to undo the one he’s got. He has been indicted and tried for commercial bribery, a felony; he beat the rap. His associates have included South Texas rancher Clinton Manges, a convicted felon; Galveston financier Shearn Moody, Jr., who is doing federal time right now; and I-30 condo scandal figure Danny Faulkner, who escaped a racketeering charge with a mistrial. Mattox’s heavy-handed fundraising tactics have passed into political legend. That all this controversy has taken its toll is evident from his low standing in early polls—the choice of fewer than 20 percent of the voters.

The glimmer of hope for Mattox is that, considering his past, his unfavorable rating among Democrats is not that high—at around 23 percent, it is well below Mark White’s. The pros interpret this to mean that Mattox’s record and feisty populist personality appeal to regular Democratic primary voters; he has sued, among others, insurance companies, airlines, automobile manufacturers, and the Dallas Morning News. He has spent eight years using the power of his office to build an organization—the latest example coming when he delighted minority activists by settling, rather than appealing, a federal court ruling that requires state judges in populous counties to be elected from single-member districts.

Mattox has at least $3 million to spend on TV—double or triple the resources of his opponents. He can try to turn his combativeness into a strength, using his record to show that he can fight for Texas. If he can make populism the litmus test, instead of character, he can point to a better record than White or Richards. He not only must beat out White but also must peel enough votes away from Richards to force her into a runoff—a roll-the-dice contest in which the ability to generate turnout will be as important as image. It’s a long shot, to be sure, but $3 million goes a long way.

Ann Richards

56, State Treasurer, Austin

Strength: Superstar image, wit, media favoritism, fanatically loyal political base

Weakness: Money, no record or stand on issues

Strategy: Emphasize ethics, character, vision

Prospect: Only question is whether she can avoid a runoff

Why is Ann Richards such a strong favorite? Listen to these numbers: Women make up 54 percent of the Democratic primary vote, and three out of four Democratic women favor Ann Richards. Put them together, and she starts with 40.5 percent of the vote before any man has cast a ballot. If just 21 percent of male voters support her, she still wins the primary without a runoff.

Like Clayton Williams, Richards is a personality figure. To her constituency she is “Ann,” just as Williams is “Claytie” to his. Her strategy is to reinforce the good feelings people have about her—and at the same time reinforce the bad feelings people have about her opponents. She doesn’t have to attack them directly, just talk about ethics and character as necessary elements of leadership.

Voters can be induced to change their minds. But Richards’ record doesn’t give Mattox or White much to shoot at (her “Poor George” keynote address might come back to haunt her against a Republican). She ran the Treasury Department without a glitch. Her only personal liability is that she is a long-sober recovering alcoholic, but when Jim Mattox tried to raise that issue last fall, the attempt boomeranged. Her biggest political liability is a lack of money. With $2 million to spend on TV, Richards would be odds-on to win without a runoff, but she’ll actually spend around $1 million.

If there is a chink in her armor, it is that she is not as knowledgeable about issues as her rivals. Mattox made her look soft on crime last spring when both of them testified at a legislative hearing. Her critics say that she is running a totally superficial campaign. But they miss the point. Her message is subliminal, not substantive, and that is what modern politics is all about.

Mark White

49, Former Governor, Houston

Strength: Achievements as governor

Weakness: Personal performance as governor, money

Strategy: Recast his image as bold and courageous, reestablish ties with minorities

Prospect: The last hurrah

Last fall Mark White was a guest on a San Antonio radio talk show, touting his record on education reform, when a retired teacher called in to ask why he had supported competency tests for teachers. Some politicians might have answered that quality education requires quality teachers. Others might have pointed out that they had raised teachers’ salaries substantially, and taxpayers had the right to insist that only competent teachers be rewarded. Mark White said, in effect, “Don’t blame me—that was the Legislature’s idea.”

In other words, he’s the same old Mark White: taking all the credit, dodging all the blame, preaching instead of teaching, setting his course by what the polls say is popular rather than by what he believes in. That’s why his negatives remain high: Three years after he lost his rematch with Bill Clements, 27 percent of the primary voters say that their impression of him is still unfavorable.

White has just about every problem a politician can have: no base (the rural conservative Democrats who were the backbone of his successful 1982 race are the biggest enemies of education reform), not enough money (the developers and bankers who were the core of his financial support are broke), and those high negatives. So what’s the use? Well, he has a history of running strongly as a challenger. He’ll attract business-oriented contributors like Fort Worth attorney Tom Schieffer, who see White as their only opportunity to get on the front row. And he does have a point that positive things happened on his watch, like a state water plan and an indigent-health-care package in addition to the education reforms—if he can persuade anybody to listen. So his media strategy is to get voters’ attention by focusing on what kind of governor Texas should have (“Sam Houston said, ‘Do right and risk the consequences.’ Tough talk from a man who put Texas first. We once had a governor like that . . .”) and wait until the last moment to reveal who fits the bill: Surprise! Mark White! If only he were running against Bill Clements, it might work.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Bill Clements

- Ann Richards

- Austin