This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

By the time you read this, I suspect—indeed, I hope—that relations between the United States and China will have taken a turn for the worse. Officials at the State Department will no doubt blame the chill emanating from Beijing on the usual suspects: diplomatic snubs, Hillary Clinton’s visit to the United Nations international women’s conference, and tensions over Taiwan. They will be wrong. I have reason to believe that the culprits will be two women from Central Texas, Mildred Boyce Breed and Tobi Deutsch Sokolow, and that the cause of the conflict will not be human rights, international trade, or other such ephemera, but something that really matters—the world championship of contract bridge.

Perhaps you are thinking that no one but a bridge player could have such a strange sense of values. All right, I confess: I’m a bridge nut. More to the point, however, so is Deng Xiaoping, the most powerful figure in the Chinese government. He’s no mullet, either. Deng is said to be worthy of the serious bridge player’s highest accolade: “He can play.” It was Deng, now 91 and ailing, who wanted the world championship played in Beijing, and it is Deng who is placing his best hope for a title—two are at stake, the Bermuda Bowl for open teams, usually all-male, and the Venice Cup for women—on the Chinese women’s team.

Sorry, Deng, but when play begins in mid-October, I’m betting on the American team that includes Mildred and Tobi. I’ve played with both of them and I’ve played against them—and I don’t know which is worse. Either way, I’m scared to death—they can play.

What’s more, they can play under pressure. High-level bridge is a rigorous test of talent, physical stamina, and mental stability. You play day after day from late in the morning until midnight. After a while your enemy becomes not your opponents at the table but yourself. Your weaknesses assault you. Your concentration wavers. You can’t remember whether your partner played the four of clubs or the five. The opponents make a spectacular play, and your discipline slips. You find yourself thinking about the last hand instead of this one. You lose faith in your own instincts. Voices whisper to you out of your soul, sending messages: Be aggressive, be conservative, play a heart. Only you don’t know whether to trust them.

The format adds to the pressure. World championship competition takes place between teams composed of two partnerships playing in two different rooms for two weeks. If, say, America is playing China, Mildred and Tobi will play a deal against one Chinese pair, and their teammates will play it against the other. Then, in the other room, the cards will be switched so that the Chinese pair in the other room will hold the same cards that Mildred and Tobi had. This provides an exact, and exacting, comparison. The luck of who gets better cards is eliminated. You play deal after deal under the pressure of knowing that an opponent of world class will be holding your cards in another room; if you make a blunder, you are certain to lose points on the deal. Last summer I played twelve deals—about an hour and a half’s worth—in a match against a team led by Bob Hamman of Dallas, who is regarded as the best player in the world. I made no errors, but I was a nervous wreck by the time we finished. How Mildred and Tobi manage to play in top form for two weeks I can’t imagine.

You would think that players who can endure this kind of intensity must be very well attuned to each other. Not Mildred and Tobi. They are the Gilbert and Sullivan of women’s bridge, a pair so different outside of their common interest that they can hardly bear to eat a meal together, yet so talented at their specialty that they can’t stay apart. “I’ve had more breakups with Mildred than with my first husband,” Tobi says. “The good thing is that there isn’t anything that at one time or another we haven’t already said to each other.”

Their partnership began in 1992, when Tobi was invited to join a team that had qualified for the trials to select the United States’ representative to the World Bridge Olympiad in Salsomaggiore, Italy. For her partner she picked Mildred, whose regular partner had decided to retire from high-level competition. Although they had never played together, their team won the trials. But the team finished a disappointing ninth in Italy, and Mildred and Tobi fought over everything from travel arrangements to whether they should complain to their captain that their partnership deserved more playing time. (Tobi wanted to; Mildred didn’t.) The partnership was off. It was on again for the 1994 world championship—they finished third in the women’s teams and led the women’s pairs until the final four deals—but they quarreled so much that they vowed to break up again, after one more tournament. They won it, of course. Somewhat to their mutual chagrin, they have decided that they are destined to be partners.

The one thing they share is a total absorption in bridge. I once asked Tobi when she and her husband, University of Texas at Austin law professor David Sokolow, had gotten married; she thought for a moment and said, “It was the year that the nationals were in Fort Worth.” Mildred still glowers at an insult more than thirty years old, when she was a teenager learning the game from her father. During a session at the Austin bridge studio, the pattern of play called for them to bypass a table where a pair of older women were waiting for opponents to arrive. As Mildred moved ahead, she heard one of the women lament, “It’s too bad we don’t get to play them. They’re easy.”

Many great bridge partnerships are also friendships, but Mildred and Tobi are far too different to be good friends. Were it not for bridge, their paths would never cross. Although both are married to bridge players and lived in Austin until Mildred and her husband moved to Waco in September, months would pass between their encounters. They don’t socialize, they don’t play bridge together except in big tournaments, and they don’t even chat about the game over the telephone. When they played in the trials last July to select the two teams that would represent the United States in China, they hadn’t discussed or played cards since January. “We played the best bridge we’d ever played,” says Mildred, “so why change now?”

Mildred, 47, grew up a country girl, straightforward and unsophisticated, in a wooded neighborhood outside of Austin. Tobi, 53, grew up a city girl, wily and worldwise, in a Cleveland suburb. These backgrounds do not foster partnership harmony. Tobi went to graduate school in social work; when she’s upset about bridge, she wants to talk about her feelings. Mildred worked in her family’s structural steel business; when she’s upset, she wants to scream. Mildred is Texas-friendly and polite to the little old ladies—LOLs, in bridge parlance—who are the backbone of any local bridge club. Tobi is Yankee-aloof and does not acknowledge their existence. She is occasionally referred to as “Her Tobiness.”

Nowhere are they more opposite than in their attitudes about travel: Tobi loves it; Mildred prefers to stay home. Since an international tournament has yet to be played in Austin, this has created a problem. After they returned from Salsomaggiore, I asked them if they got to see much of the country.

Tobi: “We went sight-seeing all over Italy.”

Mildred: “I’ll never do that again.”

Tobi: “If she does, it will never be with me.”

Mildred became the first person in the history of Western civilization to go to Italy and hate the food. “I lost fourteen pounds,” she recalls. “I had to survive on bread and butter. Sometimes I got lucky and pizza was on the menu. In Portofino I took a chance and ordered lasagne al pesto. At least I’d heard of it. The waiter brought out three wet noodles with drizzly green stuff on top. I said, ‘No, signore, mi lasange.’ He said, ‘Si, lasange.’ I nearly broke into tears.”

In China they plan to stay in separate rooms, as they did in Italy. Tobi wants to explore Beijing when she’s not playing. Mildred wants to explore her hotel, mainly in the hope of finding something edible. She says that she has heard that Western food is available in the neighborhood. I don’t think she means European. I think she means steak. Tobi’s suggestion to Mildred before their departure was, “Take two outfits and pack the rest of your suitcase with junk food.”

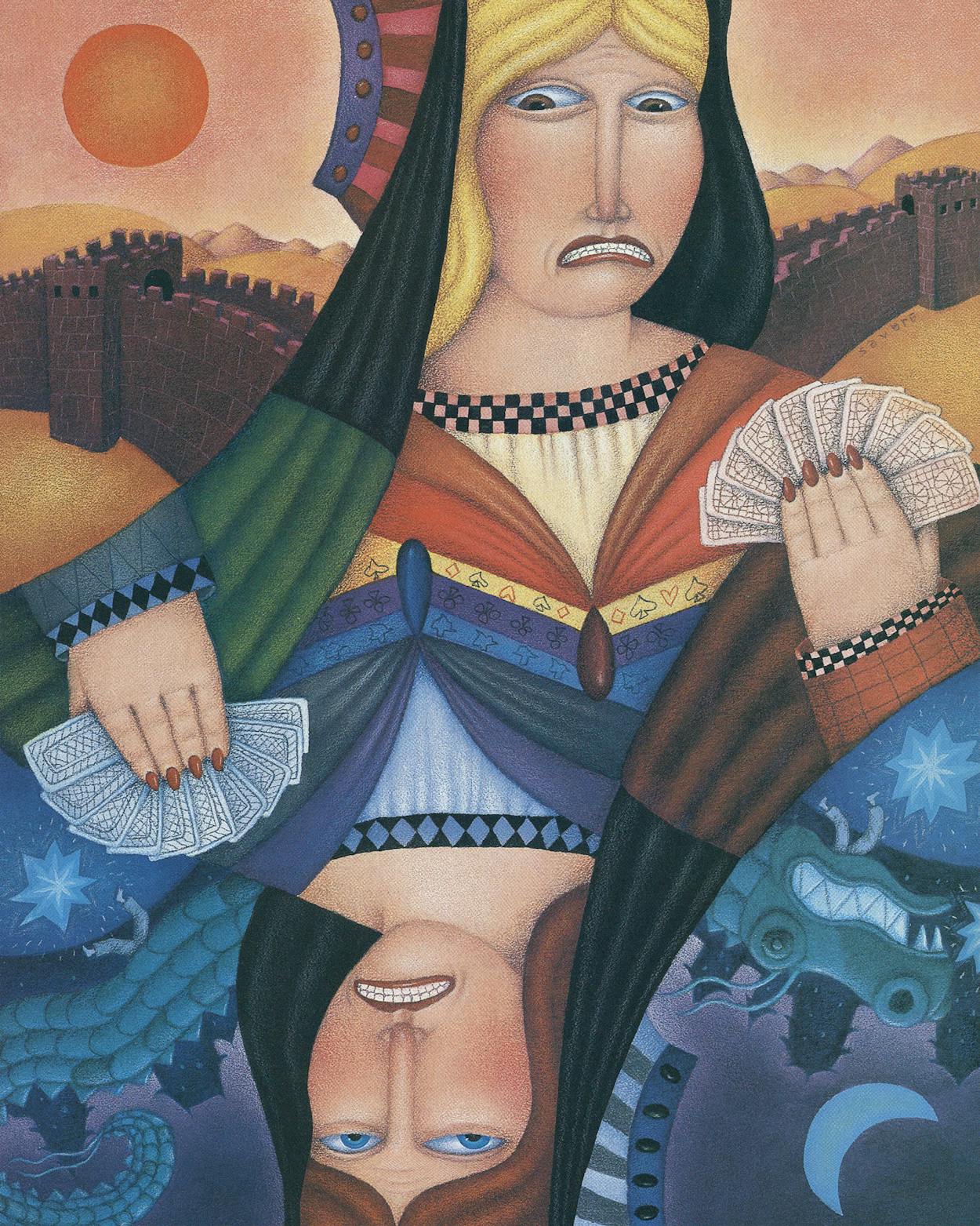

It may seem impossible for two such different people to play well together, but the one place that they mesh is at the bridge table. Each has the same philosophy about how to win: Never let the opponents do something they want to do; make them do what you want them to do. Their body language sends intimidating signals to the opposition. Tobi plays stone-faced and with serene confidence, conveying the message: “I cannot possibly lose.” Mildred sits forward, ready to pounce, frowning, biting her lip, chewing on a finger, conveying the message: “You cannot possibly win.” Her presence is overwhelming, even for a partner. Before my last tournament game with Mildred, in late September, Tobi offered me some advice: “Don’t look at her, ever.” I avoided making eye contact the entire night, and it worked. I made a misjudgment or two, but not seeing the shock or distress on her face, I didn’t fall apart, and we won. Fortunately for Tobi, international bridge is played with a screen placed diagonally across the table that makes it impossible to see your partner. The idea is to prevent cheating—scandals wracked international bridge before screens were deployed in the eighties—but for Mildred and Tobi, they prevent personality conflicts. “Behind screens,” Tobi says, “I’d put us up against any pair in the world, men or women. Take away the screens, and we’d have a hard time winning the Wednesday night club game.”

I wish I could watch the championship. International bridge is a terrific spectator sport; you can sit right behind the world’s greatest players and decide what you would do with their cards. I would kibitz Mildred, because she would have the tougher decisions; Tobi has a flair for doing the unexpected. If Mildred and Tobi had a big lead, I’d scout some of the other fifteen national teams in the tournament—especially the German, English, or Chinese teams, or the other United States team. I’d also try to find someone who could point out something on the hotel restaurant’s Chinese menu that Mildred might eat, like pepper steak. I’d go sight-seeing with Tobi. And when play was over for the day, and the screens had come down, I’d make sure Mildred and Tobi went their separate ways. The results of the 1995 world championships are available on the Internet at this address: (http://www.cs.vu.nl/~sater/bridge/bridge-on-the-web.html).

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics