Crisis reporting made Dan Rather. From Hurricane Carla in 1961 (during which he strapped himself to a tree in Galveston and filed reports for Houston’s CBS affiliate) to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Vietnam, Watergate, the Challenger explosion, and the Gulf War, the seventy-year-old Wharton native has made a career of being in the literal center of headline-making news. The events of September 11, 2001, were no different. Anchoring CBS’s commercial-free coverage of the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., Rather demonstrated the mix of tough-guy poise and naked humanity that has made him a fixture of American broadcast journalism for nearly half a century.

Three weeks later Rather talked to me by phone about thinking he had seen it all, only to find out that the unthinkable was at hand. EVAN SMITH

I WAS AT HOME ON THE MORNING OF SEPTEMBER 11. I had just stepped out of the shower when a bulletin came over the radio: There was smoke coming out of the World Trade Center, and there were reports that a plane had hit one of the towers. I walked out onto my balcony, and I could see the smoke myself. Then Andrew Heyward, the president of CBS News, called to say I’d better hotfoot it to the office.

I did think pretty seriously—for, like, fifteen seconds—about going to the scene, calling in on my cell phone, and saying, “I’m down here.” I’ve always considered myself a reporter-anchor, not an anchor-reporter. I have a discussion with myself fairly regularly about which one should prevail. On September 11 I said to myself, “I’ve spent my whole life preparing for a day like this. God, what can I do? This is what I can do. This is a day I can anchor, a day I can bring my experience to bear.”

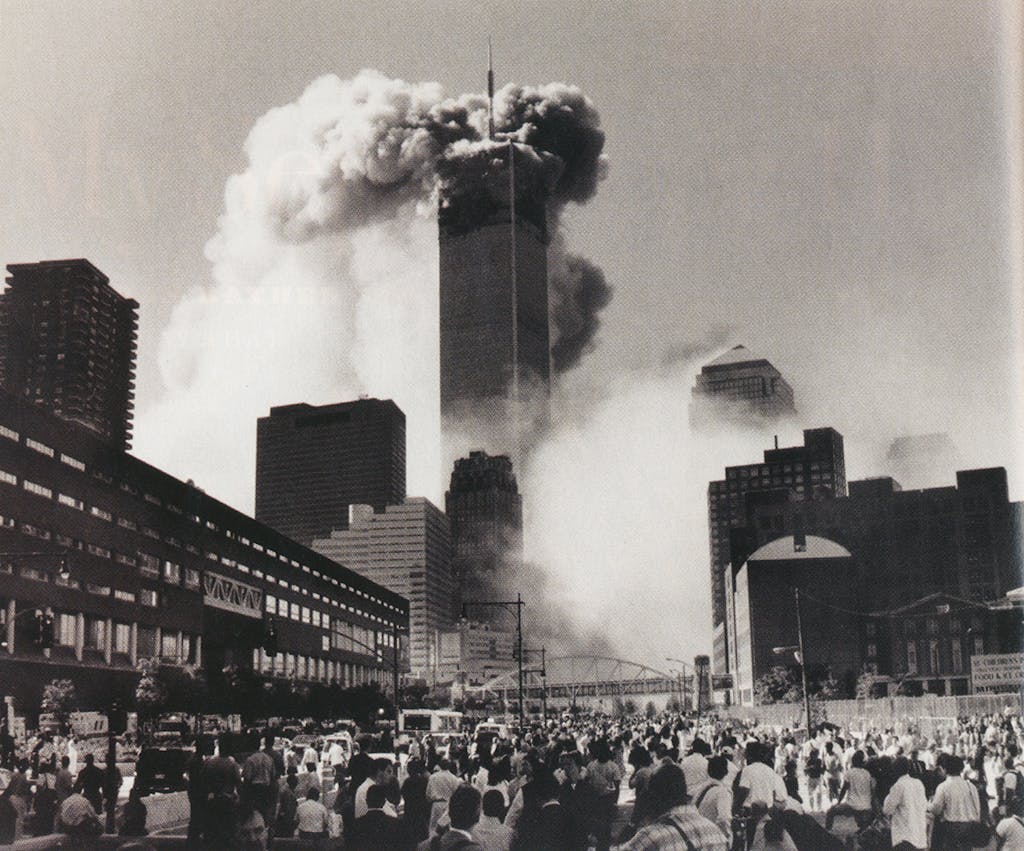

I live about fifteen minutes from our broadcast center, which is in Hell’s Kitchen, between Tenth and Eleventh avenues. While I was in the car, word came in that a second plane had hit the towers, which was inconceivable to me. Obviously it was an attack of some kind. At Eleventh Avenue I hopped out and took a look downtown. It was an incredible sight—”incredible” has to be the most overworked word in every journalist’s vocabulary, but there’s no other way to describe it. Huge billows of smoke were pouring out of both buildings. There were flames. Traffic was stopped and beginning to back up. I could see people far down the street running toward me.

When I got upstairs, we knew very little of what had happened. Andrew and I discussed what our plan was for covering the story. Our morning show [The Early Show] was staying on the air live. There was some suggestion that until we knew more, maybe we shouldn’t plan to go into total special-events coverage. Somewhere in that period, there was a report that the Pentagon had been hit. Things began to tumbleweed. Very quickly Andrew Heyward and I and Al Ortiz, our executive producer for special events, decided to get on and stay on.

MY FIRST THOUGHTS WERE, “THIS IS ALL SO UNBELIEVABLE. We have to double- and triple-check it. Can it be true? Are we absolutely sure a second plane hit?” The job in circumstances like these is to lead. In any journalistic enterprise, that means being as accurate as you can be. We have a credo at CBS, whether you believe it or not, that says: “I’d rather be last than wrong.” Then again, when you get into this kind of coverage, you have a deadline every nanosecond. There are going to be mistakes. The most responsible thing you can do is keep them to a minimum.

In my experience, the first thing you hear is likely to be wrong. Once you’re on the air, you envision a neon sign in front of you that says, “Check it out.” I feel very strongly that with this kind of coverage, you need to level with the audience—underscore it, italicize it—that we think something is true though we’re not absolutely certain. And you have to explain who your sources are. For example, the story about a car bomb going off at the State Department. The source for that, I happen to know, was a high official of the government, not just someone passing by. We questioned it, reported it, and as soon as it became clear it was wrong, we said so on the air. I don’t think this is entirely bad, by the way. More than at any other time, in a calamity the public sees the process of newsgathering. They can see the conditions under which we work.

Each of the first four days, I was on the air sixteen hours running. I’m not complaining. This is not about me; this is about the families, 13,000 at a minimum, that have lost loved ones or have otherwise gone through this. But I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t taxing—of course it was. On a story like this, I try to get zoned. I laser-beam focus so completely on what I want to do that everything else—eating, going to the bathroom—becomes not just secondary but irrelevant.

I knew from going through long periods on the air before—following the Challenger explosion, for instance—that this wasn’t going to be one day but day after day. Early on I remember saying to myself, “You have to pace yourself.” Keeping your energy up is not hard in a situation like this, but I did rely on something I call “zoom juice,” a heavy protein mixture that’s whipped up in a blender. Frankly I don’t know what’s in the damn stuff—someone on my staff makes it—but it’s good for a few reasons: It gives you a burst of energy, you can gulp it down quickly, and it’s liquid, so you’re not chewing when you come back on the air.

That first day, I got home at five-fifteen in the morning. I know from past experience that you can’t just have a glass of milk and go to bed. There’s always a long glide down. This time, there was no glide down. My head was so full. I had to be back at the office at nine the next morning. I tried to read for a while, something completely different. I read the Bible. Frequently that will take my mind off things. It didn’t. Then I picked up whatever I could find. I tried to read Richard Reeves’s new book about Richard Nixon. I got through three sentences. I ate, paced, tried to sleep. Sleep wouldn’t come.

I LIKE THIS WORK; IT’S IN MY DNA. When a big story breaks—close at hand, like Hurricane Carla, or far away, like the Vietnam War—my reaction is always primordial: Gotta go, gotta be part of it. I’m a strong walk-the-ground person, and I like to be able to contribute.

In particular, I love to do work that’s important, that’s about something more than yourself. I spent a long time on the police beat at 61 Riesner Street in Houston. After one hundred Saturday nights, you begin to question how important your work is. But when you have a story on the scale of a great hurricane or civil rights, and you get to perform a public service, that’s journalism at its best.

This was journalism at its best, but it was different from anything we’ve seen before. The Kennedy assassination comes closest as an analogy, but unlike today, when nearly everyone has at least one TV, not everyone had one back then. And even for people who had one, there were at most three places to turn for news. More likely there were two. ABC News was not fully formed, so really it was just CBS and NBC. Also, everyone is on the air today for virtually 24 hours. During the Kennedy assassination, stations went off the air at eleven or eleven-thirty at night, and the coverage didn’t go all day and all night. That’s an immense difference. The way newsrooms operate is different too. Back then cigarettes were burned into the rug and there was the faint smell of whiskey; you were in the valley of broken dreams.

One way in which then and now are more or less the same is that despite the many channels covering the news on September 11, we ignored what everyone else was doing. Only this story would have me saying that I did not once think about the competition. Generally you do: “What are ‘the biscuits’ doing?” (That’s how we refer to NBC around here—as “the biscuits.” I won’t say why, and I won’t tell you how we refer to ABC, except to say that it’s a Disney character.) I did tell myself, however, that when all this is over, I hope it’s said that we were the most accurate and that we were good at our jobs. Every reporter’s prayer, or at least this reporter’s prayer, is: “Lord, if you can see your way clear, give me the big story. And by the way, if you do, please let me be at or near my best on it.” A version of that I did think about.

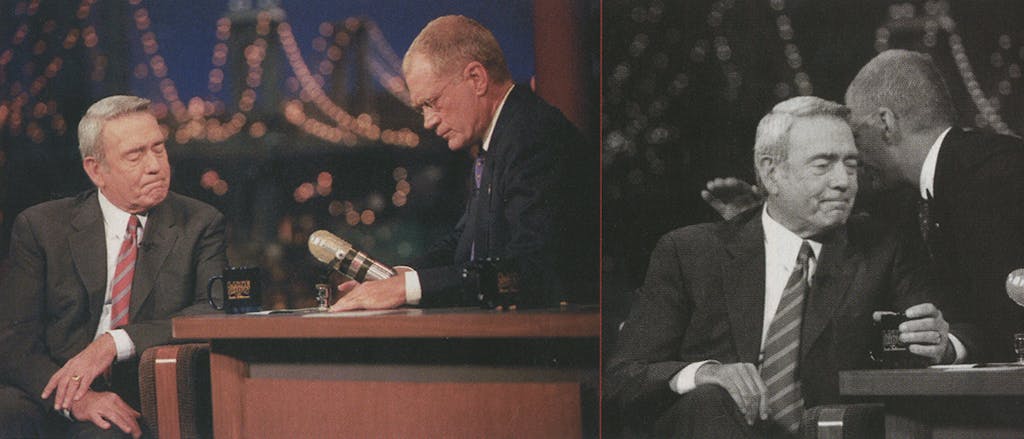

Very much on my mind through all this, though, was the idea that this isn’t about me. Being on television is like breathing NASA-grade rocket fuel for the ego. You have to be careful not to make yourself the center of anything. I have no regrets about getting emotional on the David Letterman show—I’m a human being, an American, and the leader, along with my wife, of a family—but this has not been nearly as hard for me as it has been for the firemen and the rescue workers digging up body parts.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? I think we need almost all of our resources devoted to this story, and I’ve argued that we need more. I’ve pointed out how wars are won—with firepower and staying power. Well, with respect to journalism, our firepower is people in the field who think smart, think quick, think creatively. That’s easy, relatively speaking. Staying power is increasingly difficult on any story because there’s a widespread theory in journalism that the public’s attention span is shorter now, particularly that of young people. I don’t agree with that, which runs the risk of getting me marked as yesterday’s man.

Television has difficulty with depth. It can take you right to ground zero—it has a great sense of immediacy—but we constantly have to strive to give such pictures and such stories as much depth as we can. This is not a failure of information; it’s a failure of imagination. Here at CBS we have experienced people. Our first line of correspondents are without question the most experienced in broadcast journalism. We need to leverage that experience. That’s what real leadership is about.

The problem is not with our corporate ownership, by the way. I don’t carry water for anyone, but let me tell you, we’ve gotten everything we’ve asked for on this one—total support. I’d give our corporate parents an A+. An example: There was a time, when we were on all day, with no commercials and no advertising revenue, that people began to say, “We need to get back to something approaching normalcy.” Eventually we did, but we were the last to go back to regular programming.

But I also know that we operate in a world of harsh reality, part of which is that the price and quantity of broadcast advertising was down before September 11. With the economy taking a massive hit, part of our harsh reality is how long is it going to be before we don’t get everything we want? We’re now past the first days of absolute crisis, and already we’re careful what we ask for. Personally, I’d like to have something on the air every night for an hour in prime time reporting on the war. Right now we’re on only three nights a week [60 Minutes on Sunday, 60 Minutes II on Wednesday, and 48 Hours on Friday]. Yes, we’re all about stockholder value, but having a strong news division with a reputation for integrity is great for stockholder value. Performing a public service is great for stockholder value.

WHEN ARI FLEISCHER, THE PRESIDENT’S SPOKESMAN, said a few weeks after the attack that Americans have to watch what they say in these difficult times, it was a mistake. I think Ari overall has done a great job under pressure, but he never should have said that. I haven’t talked to him about it directly, but I’m convinced he knows it was a mistake; that’s why they edited it out of the official White House transcript. I won’t say it’s minor when the spokesman for the president says something like that—it resonates and reverberates, and I hope it isn’t repeated—but I’d like to give him the benefit of the doubt.

The line dividing what’s appropriate for a journalist or any of us to say moves from time to time. I’m not sure I could defend this in a post-graduate seminar, but in the first stages of this national emergency, I was willing and in some ways am still willing to give more of a pass to the official government spokesmen than one would otherwise do. As time goes on, we’re still in a national emergency, and we stretch out for the long haul—but it’s more important than ever that you stand up, look them in the eye, and ask the toughest question you can think of. That’s my definition of patriotism in these circumstances. It can get uncomfortable. You have to face the furnace and take the heat. Nobody does it with perfection, but you keep telling yourself, “This is what I have to do.” I’m aware of what went on in Texas City and other towns and cities when journalists wrote stories or editorials critical of the president and got hate mail or were officially reprimanded. I’m here to argue that that’s not in the American tradition. We’re all taught a saying no later than the seventh grade: “I disagree with what you say, but I defend to the death your right to say it.”

That’s the larger point to be taken from all this. Those of us in journalism have to remind ourselves that part of patriotism is continuing to ask the tough questions. I’ve never subscribed to the idea that journalists should be cynical, but they should be skeptical. There’s a great and important difference between cynicism and skepticism. As they say, “You trust your mother, but you cut the cards.”