This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

One night last month I stood in aisle 31B of my neighborhood grocery store in Dallas, trying to look invisible. I mean, this was 31B—a no-man’s-aisle full of tampons, contraceptive foam, and feminine napkins. I had been on 31B only once before in my life, on an errand of mercy for a girlfriend who waited at home, watching Moonlighting with a heating pad clutched to her abdomen.

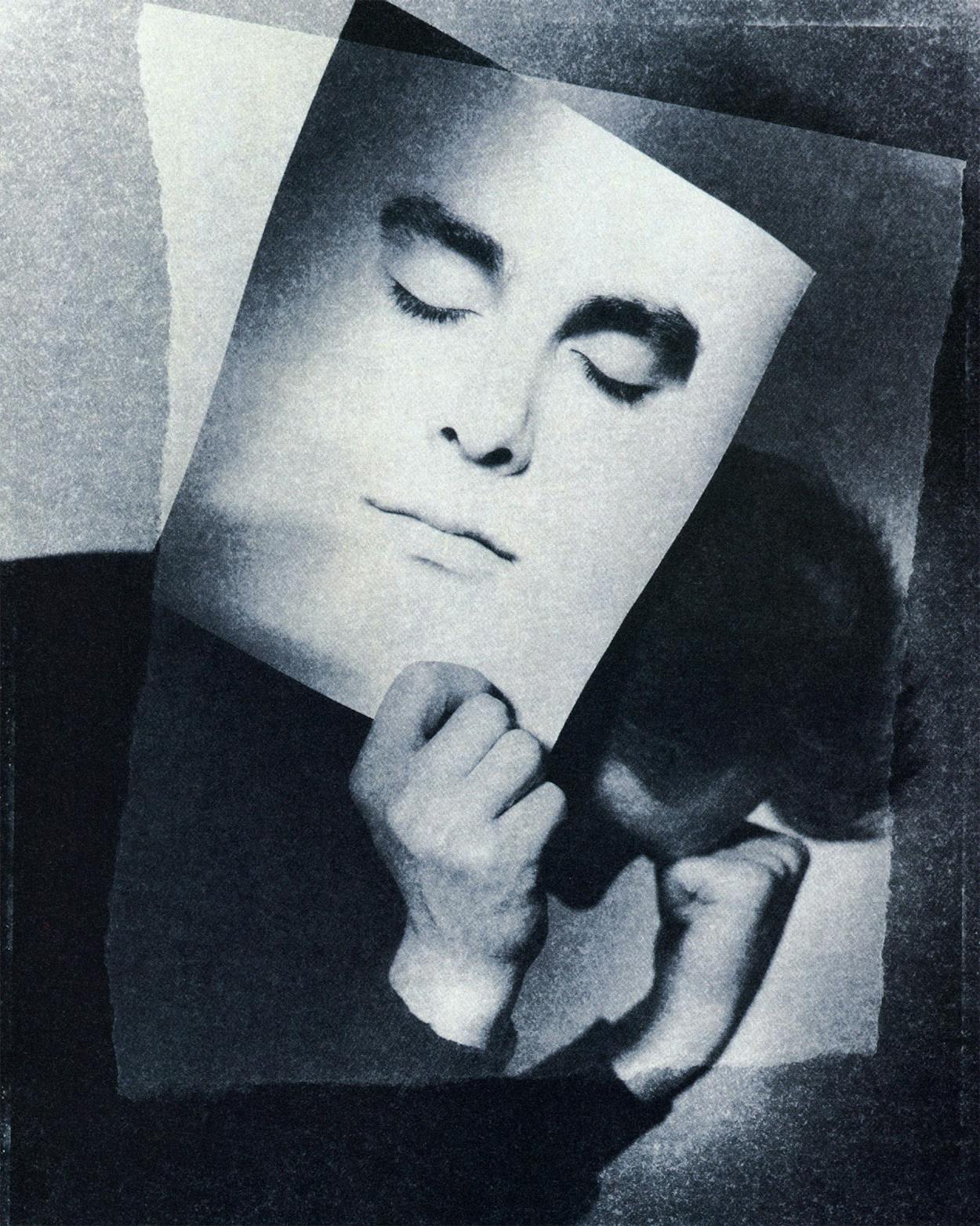

But this time I was there on my own, a few paces to the left of the tampons, staring nervously at racks and racks of condoms. I had just returned from a month-long trip around the country, writing about heterosexuality and AIDS for Playboy magazine, and I had developed a certain calm, quiet terror.

I tried to relax, to close my eyes to the horrors that lay before me. I scanned the brands for a plain, simple, no-nonsense box, one the checkout girl wouldn’t recognize. Fourex Natural Skins were the most unobtrusive-looking, but the sheep on the box disturbed me. Just above them were Excita Extra Ultra-Ribbed with Spermicidal Lubricant and Reservoir End (Extra Pleasure for Both Partners). All the others had pictures of stunning couples embracing on beaches, kissing and laughing in golden sunsets. “Why are they smiling?” I wondered.

I wasn’t. I felt a sudden rush of anger. What the hell was I doing on aisle 31B? Why should I, a nice little North Dallas WASP boy, have to buy a box of rubbers? That was the kind of thing my dad and his friends had to do back in World War II. Those were things you used to carry in your wallet when you were sixteen and throw away your first week in college. What forces of nature and man had caused me to load a cart with Ragu, Bounty paper towels, and peanut butter merely to cover my purchase of a dozen Sheiks? I stood there on aisle 3IB, and my anger grew. I know AIDS is a serious national issue, something that demands responsibility and caution from everyone. On a rational level, I can accept that. But on another level, I was steamed.

I didn’t want to buy any damn condoms.

I guess that, like a lot of people, I had been pushed too far. Ever since 1980, it’s as if some ominous conspiracy has tried to make Americans behave, to homogenize our actions and morals, to make sure nobody has fun anymore. You can’t have sugar in your gum, caffeine in your cola, or salt on your steak. You can’t have a beer without thinking of Mothers Against Drunk Drivers. You can’t have a beer at all if you’re under 21, as the minimum drinking age rises across the country. You can’t smoke a joint, because the president has declared a national war on drugs—every night on TV, a newly dried-out football star says, “Just say no.” You can’t get a job without someone testing your urine or run for office without getting a “moral report card.” You can’t buy Playboy at 7-Eleven or ride a motorcycle without a helmet. You can’t smoke anywhere. a no-drinking-while-driving bill just cleared the Texas Legislature, so you can’t tip back a cold one on the way home from work. The Federal Communications Commission ruled in April that radio deejays can’t do blue material, even if they steer clear of profanity. You can’t join the armed forces without submitting to an AIDS test, and if you test positive, you can’t get in. You can’t make a buck—much less a fortune—off an oil well or most any other business in Texas these days. Hell, you can’t even drive without wearing a seat belt in the eighties. And on top of all that, you can’t have sex with strangers, because it might end up killing you. This is why, that night on aisle 31B, I felt trapped. But I bought the condoms anyway, hiding them beneath my Tostitos, blushing when the checker had to run the Sheiks back and forth, back and forth, over the scanner before it beeped and I could flee.

To understand why I’m so mixed up and bitter, you have to understand my generation. Many of us feel cheated for having missed the sixties, when things were jumping, alive, bursting in all directions instead of meekly forming one line. When we graduated from high school in 1975, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison were all dead, and so was their era of rock and roll. We came of age after Vietnam and before Reagan—we were the last, gasping breath of the baby boomers. Our older brothers and sisters had been in the thick of the sixties—they were sent home from high school for wearing moratorium arm bands, they bought the White Album when it first came out, and they were tear-gassed at the University of Texas at Austin. They helped fight for and win the Sexual Revolution and made great gains in the women’s movement and the struggle for civil rights. The history was still beating up dust, still echoing in the streets of Chicago and Watts.

But by the time my friends and I went to college, we accepted those freedoms, that way of life, as if it were the way things had always been. That was how fast the sixties changed America. At that time it seemed like everything in our culture was based on the word “yes”: Yes, you can have all the sex you want—that’s what the Pill is for. Yes, you kids can live together without getting married—your parents will even help hang the drapes. Yes, you can read Hustler or see Wanda Whips Wall Street—the Constitution guarantees it. Yes, Yes, Yes—it’s a free country. Have a good time; enjoy yourself. But we’re in a different decade today, and it’s based on a different word. If the seventies were the Me Decade, then maybe we’ve just hit the No Decade.

Today I talk to college kids in Dallas clubs and feel relieved that at least I wasn’t in the class of 1986. They’re coming of age in the No Decade, surrounded by limitations and shrinking possibilities, being told what not to do at every turn. The New York Times Magazine recently dubbed them the Unromantic Generation: they’re so damn serious, so obsessed with planning, with their careers, with staying on track, that they have no time for anything fun.

I describe to them what it was like to be at UT-Austin in the mid-seventies, and they can’t believe it; it sounds like ancient history to them. Those were loose, free, thrilling times, I tell them. Most of my best friends—Rich, Lee, Peggy, Jack, Monika, and Jess—grew to adulthood between classes and parties in that great ex-hippie town of hills, lakes, and barefoot girls. It was the perfect college life. There were radio-TV-film classes in which students turned in erotic films as term projects: artsy, soft-focused shorts starring friends from Jester dormitory. There were trips to the country for cactus buds and psilocybin mushrooms, sandaled walks around campus, and communal life in co-ops, where everyone shared the chores and eventually slept with everyone else. There were steamy affairs with stained glass artists, punk band drummers, and clear-faced clerks in health food stores who sunbathed topless at Barton Springs. There was dancing to reggae at the Armadillo on hot Saturday nights and summertime skinny-dipping at Hippie Hollow.

That was the way we lived ten years ago, and I think we were typical of our generation. We indulged in party drugs and friendly sex—we might swallow a Quaalude and go to a pajama party, where we’d nurse a beer through the night and look for a 24-hour romance. But it didn’t mean we were drug-crazed sexual deviates. We turned out all right, became doctors and journalists and teachers, cable TV subscribers, even moms and dads.

I guess the last year things were that free was 1979. I was a rock and roll critic for the Dallas Times Herald then, and most of my UT pals had moved back to Big D. We lived in a ragtag, ethnically rich neighborhood around Lower Greenville Avenue, amid Mexican movie houses and bohemian bars, a kind of mini-Austin. We settled into our twenties, some of us having strings of two-week affairs, others living with lovers in a few spare rented rooms. We worked hard and played hard in our little chunk of Dallas, miles from the condos and singles apartment villages that sprawled to the north. North Dallas weirded us out—people our age were turning preppy up there. But under the skin we were all the same. We were young and hot-blooded, and we didn’t have to fight for our right to party. We smoked grass on our porches at twilight, with cats maneuvering between our legs, and we flirted with people at parties, at Bar Tejas, after Casablanca at the Granada Theatre.

But while my friends and I were wrapped up in ourselves, having a blast, the country around us was restless and troubled. On a deep level something was terribly wrong—too much had changed since the early sixties. Back in those days, America seemed like a simpler place. There were absolutes, things everyone could count on: Mom was in the kitchen, Dad was in charge, and Father Knows Best was a prime-time show. The sixties began with June Cleaver doing dishes in a cocktail dress and pearls; they ended with Jane Fonda in Hanoi. That’s a long way to go in ten years, and it sent the country reeling, anchorless and lost, for the ten years that followed. By 1979 we were living in a world as dark as anything Yeats had imagined. Things were falling apart, the center wasn’t holding, anarchy had been loosed upon the land. It was a world of moral relativism, a maelstrom of hard-core porn and pregnant teens, of crazed terrorists and sixth-grade dopers, of heavy metal and meaningless sex. People were floundering; they were living in a time when there was no right and no wrong, and they had lost the ability to show self-restraint, to rein things in. Jimmy Carter presided over all this confusion and to his lasting regret labeled it a national malaise.

Nobody wanted to hear that. Once the president had confirmed our darkest fears, he was history. America needed someone who would say, “Don’t worry, it’s all right, things are fine,” a relic of the days of Ike, someone who could represent what we felt we had lost. We found that someone in Ronald Reagan. Voting for Reagan was like voting no to the country we had become, like voting no to where the sixties and the seventies had taken us.

To some, Reagan’s landslide defeat of Jimmy Carter in 1980 was a joke. We had put an actor in the Oval Office—a co-star to a chimp! Reagan was a perfectly uncynical, uncomplicated man who couldn’t be accused of being an intellectual—he saw things in black and white, and he was relentlessly optimistic. So we embraced him. Something about Reagan reassured people that there really was a right and a wrong. He said it, he believed it, and we believed him. Reagan would give us back the absolutes that had been missing since the end of Camelot in 1963.

And so the No Decade was born. Since people could no longer rely on themselves for moral certainty and self-control, substitutions were made. Bureaucracy, legislation, and reforms began setting the limits that had disappeared, redrawing the lines that had faded to gray.

In December 1980, before Reagan even took office, the symbol of the new decade hit newspapers across the country. Newsweek had run a story about teenage sexuality that upset a 65-year-old Denver grandmother named Barbara Aiton. A member of the Pro-Life Commission of the Catholic Archdiocese in Denver, she sprang into action, printing up five hundred buttons that simply said “NO.” They were distributed to teenagers, and Aiton was interviewed by the Associated Press. Her story was mentioned in a Dear abby column, and within weeks 8000 chaste teens were wearing “NO” buttons on their chests, and 16,000 more buttons were on order.

There were other sudden changes. TV evangelists whom my pals and I had once laughed at over late-night popcorn suddenly became nationally respected ideologues. Jerry Falwell and his Moral Majority, Pat Robertson, Jimmy Swaggart, and Oral Roberts wanted moral fiber back in the American diet. They wanted women back in the homes raising kids, state-sponsored prayer back in the schools, and gays back in the closet. They wanted smutty magazines like Playboy and Penthouse banned from the marketplace. Amazingly, they faced little outspoken opposition, unless you counted Larry Flynt and Bob Guccione. It seemed as if the only people involved in a movement in the eighties—the only people with commitment—were those on the fundamentalist far right.

And it seemed as if all they were waiting for was a sign.

On August 2, 1982, at supermarkets, bookstores, and 7-Elevens across America, that sign appeared: a cover story in Time magazine with a screaming, blood-red headline that read, “Herpes: Today’s Scarlet Letter.”

Herpes had been around for thousands of years and had been identified as sexually transmissible as far back as the late sixties. But in the summer of 1982 it was a trendy topic. It had been in the news for months, slowly creeping toward page one, and when it appeared on the cover of Time it caused a national panic.

The herpes simplex virus, the magazine reported, was a recurrent skin disease that caused cold sores on the mouth and small, blisterlike eruptions on the genitals. The outbreaks healed in about a week, only to break out again later. Some people had herpes once and never again; a few had outbreaks as often as once a month. From a medical viewpoint, it was a relatively harmless disease except during childbirth. Reduced to simple terms, genital herpes was just a cold sore in the wrong place. But in other terms, it was a sex disease that would never go away.

That was how it was presented in the Time story. Herpes horror stories were told: a pregnant housewife wanted to cut away her skin when she learned her herpes might be passed to her baby in childbirth if the virus was active; one man caught it on the only one-night stand of his life; a cab driver was so terrified of giving it to someone that he had become celibate; coworkers of a woman who had herpes circulated a petition to ban her from the office.

Time said that as many as 20 million Americans had genital herpes that summer and that as many as half a million more might get it within a year. The story was summed up in perfect No Decade style: “Perhaps not so unhappily, [herpes] may be a prime mover in helping to bring to a close an era of mindless promiscuity. The monogamous now have one more reason to remain so. For all the distress it has brought, the troublesome little bug may inadvertently be ushering in a period in which sex is linked more firmly to commitment and trust.”

Across the country, people read the Time story and panicked. The 20 million people with genital herpes suddenly felt like lepers. There was even talk of tattooing the letter “H” onto their foreheads. Few people stopped to ask, “What’s all the fuss about?” Those who did, writing in the New Republic and the Nation, accused Time of fanning the herpes scare, of pressing forward a national agenda to crack the whip and make folks behave, no matter what the cost.

Naturally, the Moral Majority saw herpes as a gift from heaven. Sermon after sermon, in nearly every church and denomination across the country, included references to herpes as God’s answer to our country’s recent sexual debauchery. The good Lord was putting an end to the Sexual Revolution, trying to instill morals back into the American way.

Did it work? all I know is that my friends and I were terrified—it was all we talked about that summer: “You shouldn’t go out with him. I’ve heard he has herpes.” “You slept with that girl from the party? You’re crazy! Weren’t you afraid she might have herpes?” We discussed not-so-subtle ways of asking dates whether they had it. “Do you have herpes?” was suggested as an icebreaker.

“I don’t have to worry about it,” my friend Lee would gloat, nodding toward his house, where he lived with his girlfriend of two years. “But you guys,” he shook his head. “You guys are in trouble.”

Herpes didn’t really end the Sexual Revolution. But it did put a germ of doubt, of hesitation, in most people’s minds, one that hadn’t been there since the early sixties. For the first time since the Pill was discovered, having sex wasn’t worry-free.

That summer, when herpes was being called the plague of the eighties, I came home one day with a sack of groceries, and—I remember this very clearly—I turned on All Things Considered, a news program on National Public Radio, and started putting away my frozen pizzas. I had tuned in on a story about an immune disease that made people unable to fight off simple illnesses like colds or the flu. They invariably ended up getting cancer or pneumonia and dying. The odd twist to this disease was that it affected only homosexuals and Haitians. That’s weird, I thought. But at least it wasn’t something I had to worry about.

It’s funny, but back in ’84 and ’85, I still clung to the belief that the eighties were great. Even though it was a decade of IRAs and condo time-sharing, of Saab Turbos and imported water, I had decided to be different. I focused on one of the few groups that hadn’t fallen in line, that didn’t own suits or do aerobics: the kids in the cool scene in Dallas, who hung out every night at Tango, On the Air, the Starck Club, and Club Clearview. I had cut myself off from how people were really living and thought I was in a time of glitzy, post-punk excess. In my world, girls in rubber dresses danced to British new wave, their lips painted white, their hair a dazzling wreck of mousse. Guys wore baggy trousers and black leather jackets; they wore flattops or long, wild locks. These were cool kids, and they were like my extended family. We danced to the Cure, New Order, the Clash. We puffed clove cigarettes and did flaming shots at the bar. In the daytime—which most of us disliked—you could be anything. You could be poor, rich, sixteen, stupid, brilliant, portly, plain, on the run from the law. But nothing stopped you from being hip and in the scene on eighties’ nights.

The summer of 1985 was the last time I held onto my delusions, and they were at their richest, their most deluding. That summer we were all on Ecstasy. CBS News called Dallas “the Ecstasy capital of America,” and it was true: at the Starck Club on Saturday nights it seemed as if a thousand people were on the then legal designer drug. You could buy an aspirinlike tablet of X for $10 or $15 and be in a delirious mood for hours. Everyone loved everyone else on X; it was like the free-love sixties or those laid-back days in Austin. Sex was great on X, and it was bountiful. For a short time the eighties seemed like the time to be alive, the most partying decade since the Roaring Twenties.

But the morning after X, blood pumps through your body like Karo syrup, and your brain feels like a bag of gravel. You’re sullen, tense, anxious. You want to lie down, even if you’re supposed to be at work, even if you’re supposed to be the best man at someone’s wedding. I would feel that way and think it was just a designer hangover. But it was actually reality setting in. One cold X hangover day I came to grips with the truth. I wasn’t living the eighties life—I was trying to escape from it. So I swore off X, cut down on drinking, and even began staying home a few nights a week.

I did this, and something occurred to me: by swearing off X, I was saying no to myself. Everyone rebels, everyone has to learn to grow up. There’s a time when you slow down your partying and start to strive in your career, when you settle into a monogamous relationship, maybe get married and have kids. And in each stage of the process, you grow a little, you gain a certain strength and character. That may be the worst thing about the No Decade. It denies people all those stages of growth and change. When simply forced on the masses, rules can’t possibly mean as much. Being told what to do at every turn robs us of our right to choose—to decide when we want to say no for ourselves.

Before last winter, few heterosexuals had worried about AIDS. But then came the controversy over condom ads on TV, dire warnings from the surgeon general that AIDS was a threat to everyone, and another cover story in Time. But now, no one accused the magazine of blowing things out of proportion. If anything, people wondered why they hadn’t been warned before.

“The Big Chill—How Heterosexuals Are Coping With AIDS” hit the newsstands February 16, 1987. Inside was the grim latest news. Heterosexual infection accounted for nearly 4 per cent of the AIDS cases in the country, a figure expected to rise to 5.3 per cent by 1991. That was only the number of heterosexuals who had developed the disease, which has an incubation period of six months to several years. The number of straights carrying the virus could only be estimated. More than one million Americans were thought to be carriers, and more than 90 per cent of them didn’t know it. This was not a disease that caused a little cold sore and went away. This was a disease that killed you.

According to Time, 85 per cent of the callers reaching an Atlanta AIDS hotline were heterosexuals, and 40 per cent of calls to a similar hotline in Chicago were from frightened women. “Most say, ‘I had too much to drink, and I went home with this guy,’” said the Chicago hotline’s director, Mary Fleming. “I hear stark terror in heterosexual women, who are deciding to be celibate.”

This is what led me to aisle 31B of my grocery store that night. The guys and I feel awkward and uneasy about the whole thing; we’ve never had to be responsible about sex. The Pill let us off scot-free. In the old days—say, 1982—we’d careen around town in a 1966 turquoise Tempest, getting royally stewed and talking about women. But now, in 1987, our boys’ nights out are relatively somber, almost funereal. We agree to meet someplace, and we arrive separately, strapped in our cars by seat belts. By our second drink we think compulsively, “Let’s see, was that my second or third? It’s just been thirty minutes. . . . Better eat some fries or something to keep that old blood alcohol below point ten.” More than likely, we go to only one bar. And instead of salivating over the luscious brunet at the bar, we’re more likely to dive into desperate AIDS talks, much the same as our herpes talks of five years ago. Someone might say, “Have y’all ever slept with a girl who’s been with a bisexual?”

Everyone grips the table, stares into space, reels their memories back across their twenties, into their late teens. Bells ring: “Oh no! That girl Denise, in the dance department at SMU! She always went out with—gulp—ballet dancers!” Or “Remember Sally? You know that guy she broke up with to go out with me, the one with the blow-dried hair and the real fresh breath? You don’t think . . . no. No!”

Suddenly, the bill has arrived. Men and women are equal partners, and we have to do the right thing. But what is it? The idea of safe sex, of monogamy, of rejecting casual encounters, goes against our very grain. How are you supposed to brag in the locker room in 1987? “Hey guys, guess what happened to me last night? I met this hot blond babe and got her to my place, and as soon as she’s inside, she strips to the skin.” “Wow . . . what did you do?” “I told her to put her clothes back on. I looked at her and said, ‘Just say no, Trixie, just say no!’” Is that what it takes, to be a he-man in the No Decade? Will this be the new machismo?

Women seem to feel less ambiguous about it. Evidence shows that men are much more likely to give women AIDS than vice versa, so women heterosexuals are those who are really most at risk. My women friends are very concerned, very scared. When the Dallas Times Herald published a six-week study called “Sex in the ’80s: Coping With the AIDS Scare” in its March 29 Sunday edition, one of my friends talked to me about it, waving the front page as if it bore the news of her best friend’s death.

“Did you read this?” she wailed. “It has these safe-sex guidelines—it says to use Saran Wrap for oral sex. It says you shouldn’t brush your teeth before sex because it can make microscopic cuts in your mouth. But that’s the one time everybody brushes their teeth. Condoms, sheets of latex, rubber gloves, spurting tubes of nonoxynol-9 . . . guys aren’t going to do all that.”

Another friend of mine—let’s call him Dan—was the first guy in my gang to face facts. His girlfriend read a cover story in the February Atlantic called “Heterosexuals and AIDS: The Second Stage of the Epidemic” and called him at work, flipping out.

“We’ve got to use condoms from now on!” she screamed.

“Huh?”

“Condoms, condoms! They’re the only thing that can stop you from getting AIDS.”

Dan and his girlfriend had been monogamous for nearly a year, but she was worried about the legions of young women he had entertained for six years before that. Any one of them could have harbored the deadly virus, and using a condom was the only way she could be sure she was safe from Dan—if he hadn’t infected her already.

“What about you?” Dan shot back.

“What about all the guys you’ve dated?”

“If you’re going to insult me,” she said, “I can hang up the phone right now.”

Things have been going downhill for a long time, but now life in America is taking on the quality of a Fellini film. How are we supposed to live in times like these? I wonder what famous romantics would do if they lived in the eighties. Can you imagine Marc Antony grilling Cleopatra about her sexual history? Or Elizabeth Barrett Browning asking Robert to use a Sheik? King Edward abdicated the throne of England for the woman he loved, causing the greatest romantic scandal of the twentieth century. Can you picture him winding Saran Wrap around Wallis Simpson the night they first made love?

Many people are trying to find something good in AIDS. They say it’s bringing back romance, putting an end to casual sex, setting America back on the moral track. But they’re ignoring that it is part of a larger picture. Throughout the eighties there have been more and more encroachments on our social freedoms, our civil liberties. Why haven’t people protested? Why does no one charge the barricades? Even liberals merely grouse and complain when magazines are yanked from the convenience-store shelves and when congressmen’s wives argue for the censorship of rock and roll. They complain, and then they accept it all. I think it’s because, deep down, maybe we wanted a No Decade to happen. In an uncertain world, being told what to do can be comforting. It’s like having a strict father. We may complain, but we rely on him to make sure we don’t go too far, that we don’t go wrong, that we’re safe. But this year, for the first time since 1980, cracks have begun to appear in the No Decade’s fragile foundation. From Irangate in the Reagan administration to reports of wife-swapping and call girls at the PTL ministries, the institutions that have led us down a righteous moral path are crumbling.

Today I walk through the dark, echoing streets of the warehouse district of Deep Ellum at night, watching people pass me from Club DaDa toward the Prophet, kids who laugh and hope there’s more fun around the corner. But it’s hard for me to find much joy in it. I stand on Main Street, the quiet block between the bar-dotted blocks of Elm and Commerce, and I can hear the competing sounds of bands, the tinkle of distant, breaking bottles, the giggle of girls smoking grass in a parked car. Once I would have been thrilled by the action, by all that possibility, by the fact that at 1 a.m. the night was still young. But I’ve been to New York and L.A. lately, and I know what’s coming: that chill dread, the fear of AIDS. I detect a collective feeling of resignation and defeat spreading across the singles scenes of Texas. And I sense that things are never going to be the same again.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads