The traditional way to prepare Texas barbecue is in a pit, the more smoke-infused and grease-encrusted the better. The word “pit” harks back to the days when meats were cooked over smoldering coals in an earthen pit or trench, especially for large gatherings. Nowadays, such buried ovens are extremely rare, but the word lingers on.

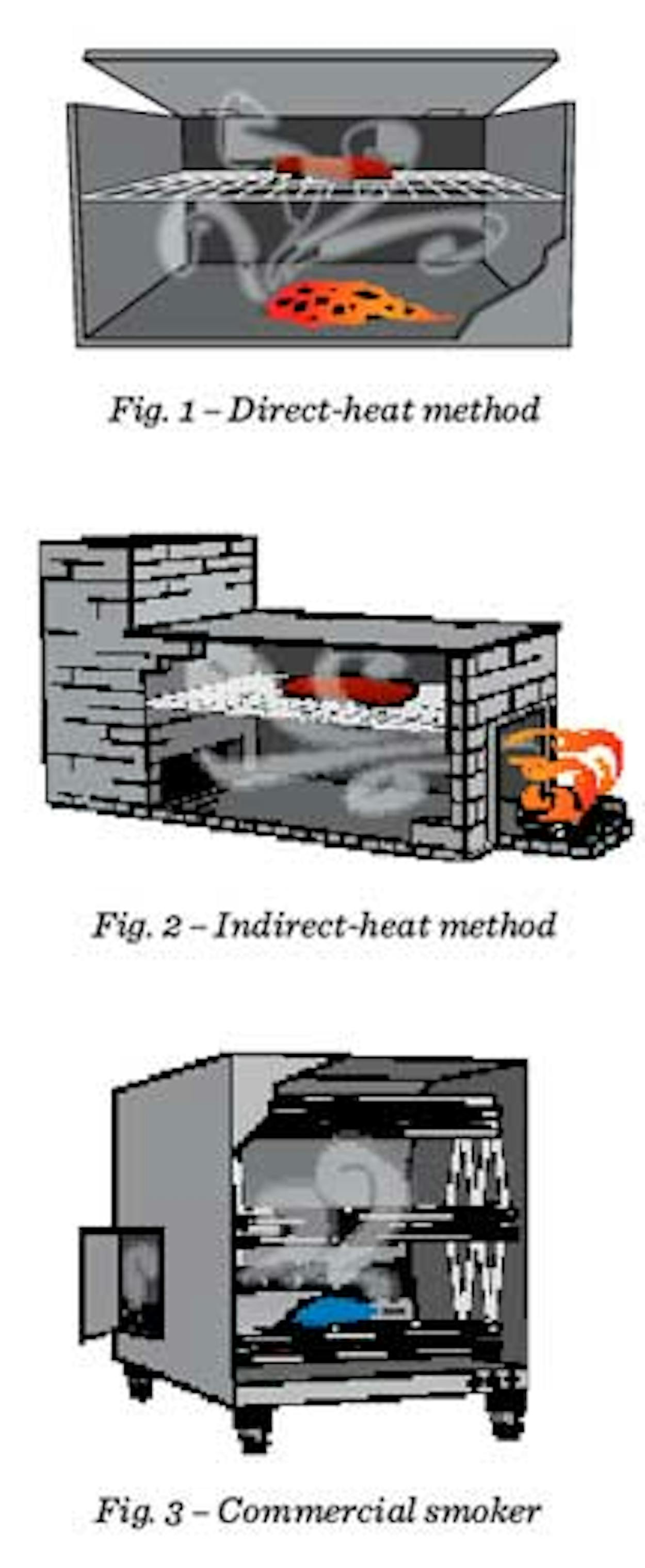

Pits can be divided into three types. The first is a massive brick or metal box with stationary racks set a couple or more feet over the wood or coals. This is the direct-heat method (fig. 1), also known as cowboy style. Cooper’s in Llano is well-known for this method. As the meat slow-roasts, juices and fat drip down and flare up, creating a delicious smoky char. The danger is that the meat can overcook and dry out quickly.

The second type consists of a container, usually made of brick, with a wood fire or coals at one end and racks at the other. It might be likened to a short chimney laid on its side. Hot smoke is drawn over and around the meat. This is the widely used indirect-heat method (fig. 2). It produces deep smoky flavor but can be unpredictable. Slight changes in the size of the meat, diameter of the wood logs, even the outdoor temperature, can throw off the results. Smitty’s and Kreuz, in Lockhart, famously practice this style, as does our favorite joint this time around, Snow’s, in Lexington.

The third type makes barbecue purists cringe: the commercial smoker (fig. 3). Basically, it is a big, tall stainless-steel rotisserie oven with slowly rotating meat racks. In some instances, wood is still the primary heat source, with gas or electricity as a backup or igniter, but many cook exclusively with gas or electricity, getting their flavor from an interior “wood box” that introduces smoke into the pit. While the meat that comes out of these devices is often tender and juicy, we have yet to find one that can truly impregnate a brisket with that rich, seasoned smokiness the old-style pits deliver. Lamberts Downtown Barbecue, in Austin, and Wild Blue B.B.Q., in Los Fresnos, use commercial smokers.

Is Texas barbecue at a crossroads, pit-wise? Maybe. Old-school barbecuing takes skill, dedication, and somebody who’s willing to feed the fire at three o’clock in the morning. That’s why commercial smokers are gaining ground. Not only do they eliminate the night shift, but they require less experience to calibrate the delicate balance between time, temperature, and meat. Still, the gastro-aesthetic question remains: When you’ve driven forty miles out in the country for a brisket-and-rib plate on a Saturday morning, what do you want to see—the blue gas flames of a brand-new smoker or the glowing red embers of an ancient brick pit?