This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

About midnight on January 13, Iris Siff, 58, a woman who often worked late on her job as managing director of Houston’s Alley Theatre, was robbed and strangled in her office. The following day, the police took into custody Robert Taylor, 30, an employee of Security Guard Services, Inc., who was on duty at the Alley at the approximate time of Mrs. Siff’s death. Investigators said that a note found near her body matched samples of Taylor’s handwriting, and reporters turned up the information that the security guard was an ex-convict. In September, after serving forty months of a prison term, Robert Taylor had been paroled in Ohio.

Taylor was not charged in the killing of Mrs. Siff. After holding him for four days, the police let him go. A tipster had given them another suspect: Clifford X. Phillips, 47. Police detectives traced him to California and in mid-February arrested him there. He was returned to Houston and indicted for murder.

In a confession to the press, Phillips said that on the night he killed Mrs. Siff, he had entered the Alley through an unlocked door, although he had a key. From old news accounts and perhaps from leaks in the criminal records system, reporters learned that Phillips, like Taylor, had a busy criminal past. He had been in and out of jail since 1952 and in 1970 had been imprisoned in New York for the killing of his three-year-old son. After leaving prison, Phillips hunted for work as a house painter, but in October he, like Taylor, had come knocking where jobs were plentiful: in the private security industry in Houston. Clifford X. Phillips was Robert Taylor’s predecessor at the guard post in the Alley Theatre.

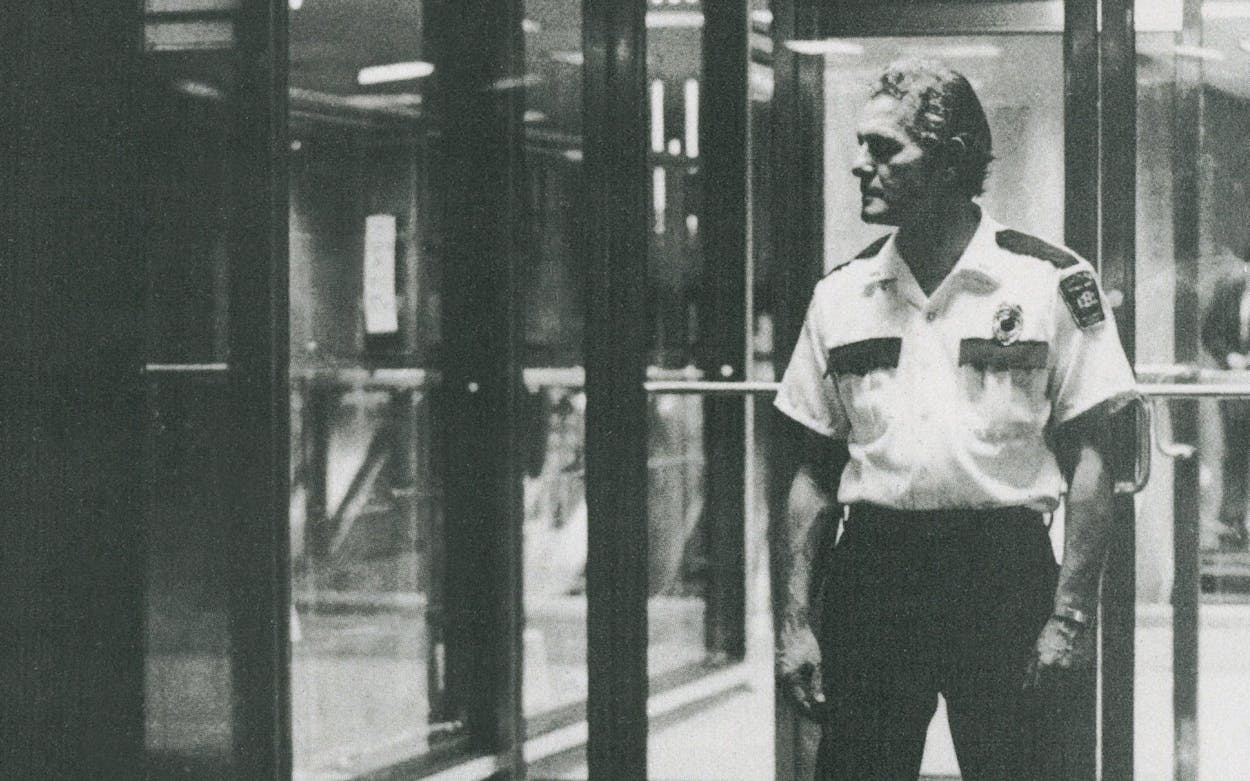

News about the criminal records of Taylor and Phillips rattled and worried apartment tenants and office workers, who trust in the guards hired to sit in building foyers. Almost everyone in Houston lives a part of his life under the presumed protection of private security services. Office buildings, apartment complexes, residential neighborhoods, and factories are all patrolled by private guards. Guards are on duty at some schools and churches and at most events that draw a crowd: dances, carnivals, even weddings and funerals. The confidence placed in security guards is based largely on respect for uniforms and is often unwarranted. While most guards are well-intentioned men whose chief aim is to earn an honest living, Houston police files are spotted with reports about guards who put on uniforms in bad faith. Last November, for example, Houston policeman Monte R. Fogle wrestled with a chain-wielding intruder at a Houston industrial site. After a chase, other policemen arrested the suspect, who had escaped his grasp: a security guard, in uniform. That same month, M. A. Linn, an Intercontinental Airport policeman, detained a man who attempted to board a flight while carrying a pistol, a nightstick, a can of chemical Mace, and a supply of ammunition. Linn’s suspect was a uniformed guard, too. In March, guard Lang Dac Nguyen of Houston was charged with arson; investigators say he set fire to the building he was guarding.

These stories—and others could be told—are illustrative of a grave and dangerous problem in Texas: our guard services do not know who they are hiring to protect us. It is all too easy for a man with a criminal past to find work as a guard, and the profession—if it can be called that—is attractive to crooks, because it gives them a chance to exploit positions of trust. On a guard job, a felon can learn where the unlocked doors and unwatched treasures are and how to foil the security systems designed to protect us and our valuables.

Early in February I went to Houston to test hiring and training practices in the private security industry, by applying for security guard jobs under paper-thin pretenses. My objective was simple: to get employment offers from companies across the industry. Over the course of three weeks I applied for work at eleven companies, always telling the sort of lies that a felon might tell. One turned me away when, as a test, I said that I didn’t have a driver’s license. Of the other ten, six cleared me for hiring, and I never heard from the rest. Four issued me uniforms with orders to report for work, and I actually worked for two. Nobody discovered that I was lying. Nobody turned me down for a job. Nowhere did I find hiring safeguards sufficient to keep a Robert Taylor or a Clifford X. Phillips from wearing a badge of trust.

On the Friday morning of the week I arrived in the city, after looking over twenty or thirty ads for guards in the morning editions of the Post and the Chronicle, I decided to apply at a company located in the Westpark district in West Houston. I chose Majors Security Services as my target for the commonest of reasons: it was near the apartment where I was staying. Its office, on Rampart, was in a complex of low, flat-roofed buildings designed like a self-storage center, with an overhead door to serve each tenant. Several of these cubicles were home to small tax, consulting, and research firms. I found the office I was looking for next door to a Chinese wholesale grocery. Majors Security may not be the pride of the industry, but its clients include Saks Fifth Avenue, and a plaque behind the receptionist’s desk said that several years ago the owner had won an award.

The receptionist gave me an application and I sat down to fill it out. The form was fairly standard, asking name, age, place of birth, and other identifying questions. There were the usual questions about arrest and employment records and, at the bottom, a place for signing an oath. The oath said that I had never been convicted of a crime of moral turpitude. I once went to law classes for a year, and I still don’t know what a crime of moral turpitude is. I signed the oath anyway.

My answers to questions asked on the form were a mixture of lies and truth. I used my real name, age, and place of birth but claimed to have been arrested only once, for drunken disorderliness. That is not true. I have a jail record some dozen arrests long—I was a civil rights and antiwar agitator during the sixties—but I’ve never been jailed for drunkenness. I lied about my employment record, address, personal references, and numerous other things. I posed as a West Texas welder who had recently moved to Houston to forget a divorce. The principle that guided me in filling out the application was one a convict would use: tell the truth if you can, but lie as necessary to get the job.

When I turned in the application, the receptionist, after consulting with a short-haired woman in the rear of the office, told me to return for an interview on Monday. I showed up at midmorning, and at about eleven o’clock the short-haired woman called me to her desk. She examined my driver’s license and asked if I was in the habit of drinking while at work. I told her that I didn’t drink at all. She asked if I smoked pot, and when I said no, she told me that I could be hired if I could pass a lie detector test.

I hadn’t expected anything like that, and the prospect put me on edge. If the test stuck to the questions of drug and alcohol use, I might pass it, I figured, but if I were questioned about my background, there was no way I could tell the truth. There was no turning back, either. The woman was already on the phone, making an appointment for me to be examined that afternoon at one of Houston’s thirty private lie detector or polygraph agencies. (For more about lie detectors, see “The Box,” by Jim Atkinson.)

The lie detector service, Donald A. Cole & Associates, was located in a modern, quiet office building on Richmond near Greenway Plaza. No sooner had I entered the waiting room than a secretary warned me that smoking was forbidden in the office.

I gave my name and sat down. Shortly, a nondescript man in a brown suit called me back to his inner office. He sat down behind his very uncluttered desk, placing a form in front of him. In a neutral voice, he began asking me questions. Most were of the same sort asked on my job application for Majors, but there were new ones, like “Have you ever filed suit for a job injury?” “Have you ever stolen from an employer?” and “Have you ever lied to an employer?” In effect, I had to add new lies to the ones I had told Majors, though the new ones were whiter, in my book. For example, I told him that I had never lied to an employer, but I am 36, I’ve worked all my life, and I’m quite sure that I have lied to employers, though I can’t remember when or about what. As I answered the questions, my examiner made notations on his form.

To his left sat a clean ashtray. I was nervous and was tempted to calm myself with a cigarette. After thinking a moment, however, I decided not to. In the clean, scientifically neutral atmosphere of his office, I told myself, the ashtray was probably a trap: whoever smoked during interrogation would probably come under suspicion. I suppressed the nicotine urge and kept on lying.

After questioning me for ten to fifteen minutes, the examiner led me to a completely unadorned room, furnished with only a desk and a chair that was turned toward a blank wall. He quickly seated me, telling me to look straight ahead, not at the polygraph machine on the desk or at him. Standing at my back he placed a piece of plastic tubing around my chest to measure respiration. Then he fastened a blood pressure cuff onto my left arm and connected two or three metal sensors to the fingers of my right hand, to measure perspiration. He told me not to move, to breathe calmly, and to answer his questions with a simple yes or no.

After a few seconds, the grilling began. First he asked questions like “Are you thirty-six years old?” and “Were you born in Oklahoma?” I truthfully answered yes to these. In the same steady, neutral voice, he then asked, “Did you tell the truth about your employment history?” and “Did you tell the truth about your arrest record?” I lied on these, as any convict would have. His last question, I believe, was “Have you ever lied to an employer?” I said no.

He shut off the machine and began making preparations of some sort; I couldn’t tell exactly what. He asked me what I had meant when I told him that I had never lied to an employer, “It’s like I said during the interview,” I insisted. “I’m old enough that I’m sure I’ve lied about somebody being sick, or somebody being late to work, or something like that. I don’t know exactly what I’ve lied about, but I put down on the form that I had never lied, because I’ve never lied about anything important.”

He told me to keep my eyes to the wall and, after a moment, turned on his machine and began asking questions again. His first queries, I believe, were the same ones about my name, age, and birthplace. His last, I think, was “Is it true what you told me a minute ago about never having lied to an employer?”

“Not about anything important,” I replied, hoping to throw his machine off by not responding with a simple yes or no. The examiner did not protest my answer, and he promptly shut off his polygraph. He told me to rise, and he ushered me out of the room, shaking my hand and wishing me good luck as he did. He said that if I would call the security company in an hour, I would be told the outcome of the test. When I did I was told that I had a job, beginning the next day.

The company issued me a brown and tan uniform that looked like something a bullring cop might wear. Though it is illegal for a guard to carry a pistol until he has been trained and licensed, he can use a shotgun or rifle in his work, and on my first job, as a night guard at the A. J. Foyt Chevrolet dealership, I was given a shotgun. The work was lonely, cold, and boring; I quit after one night. In an effort to keep me, the company offered new assignments, which I took. I spent one day at Saks Fifth Avenue, watching shoppers and wrangling with discourteous parking space competitors, then went on guard at an office building on Main, where I stayed for several days before quitting for good.

After my success with the first company, I decided to up the ante on the job-hunting game. I began seeking jobs under a false identity. I didn’t think it would be easy to lie to a professional polygrapher about things as fundamental as name, age, and place of birth. A friend had advised me that criminals sometimes prepare themselves to “beat the box” by taking tranquilizers before exams. I decided to try the trick myself. An hour before my second polygraph interrogation, for Southwestern Security Systems, I took an ordinary tablet of Valium.

This test, in a building like the first, with an examiner who used a similar procedure, involved questions that were a bit tougher (and probably intended to smoke out union organizers). “Were you planted on this job?” the examiner asked me. I said no, I wasn’t. “Have you stated your real reasons for wanting this job? Are you satisfied with the wages you have been offered?” I sat and lied and, thanks to the Valium, was not unnerved. I passed. The company offered me a job at a savings and loan office, but I balked when I was told that deductions would be made from my salary to pay for my uniforms.

By the time I took my third exam, I was emboldened and pushing my luck. I wanted to see if polygraph tests were any good at all as a hiring tool. I decided not to protect myself with relaxants and to use a new, more stringent standard for formulating answers: if you can possibly lie about anything, do. The exam, for a job with the Wackenhut Corporation (the third-largest security company in the nation), was held at the offices of Ernie Hulsey & Associates, a firm employing about a half-dozen polygraphers and located in a building on the Southwest Freeway near Bellaire. My examiner was a feisty thirty-year-old in a dark three-piece business suit, not a sedate, low-key character like my previous inquisitors. Instead of discouraging me from viewing his apparatus, this examiner began by showing it to me.

A polygraph machine is a device about the size of a stereo tuner with wires and cords leading out from it. Like an electrocardiograph, it has a series of needles that make markings on a roll of graph paper. The other machines I’d glimpsed were portable affairs in metal boxes, but the one shown to me for the third exam was permanently mounted into the desk of the interrogation room. My examiner gave me an animated little lecture on its operation—a talk calculated, no doubt, to arouse my anxiety.

“If you’ll think back to when you were a little boy,” he said, “you can probably remember that sometime your mother asked you a question about something you had done, and you lied. You were afraid when you lied, because you knew that if you got caught, you’d be punished. Well, this machine works the same way. Although nothing can perhaps approach the level of fear you felt as a child for your mother, there will always be a discomfort and a trace of fear when you lie. And this machine,” he said, sweeping his hand over it, “will tell us when you are nervous because you are lying.” The lecture kindled a little dread in my heart.

The examiner began the familiar questions. Because I was determined to tell grand lies, and because I’d already told them on the form his office had given me, I answered yes to queries like “Are you thirty-four years old?” and “Were you born in Texas?” I maintained my lies about my employment and arrest record—this time I claimed no arrests at all. The examiner asked me perhaps ten questions, the usual number, and then stopped his machine, letting off the pressure on the arm cuff as he did so. In plain view, he changed the roll of paper in his machine and added ink to one of its vials. After completing his tasks, he puffed up the cuff again and repeated the questions, as polygraphers always do. I lied again.

At the end of the exam, which took about fifty minutes, he laid out in front of him the two paper tapes. With a felt-tip pin, he made marks of them, charting their high and low points, writing numbers and letters below. The procedure appeared very scientific to me. I looked at the machine, which seemed formidable, and at my examiner, who seemed to be intent on his markings. Then I looked at the charts, which didn’t appear identical to me. I decided that I had probably flunked this, my third and toughest test. The suspense got the better of me. “Did I pass?” I asked him, unable to contain myself.

“Well, yes, you did,” he remarked after a pause. “Why do you ask—did you lie?”

Preemployment polygraph testing may not detect anything, and it is an expensive procedure, usually billed to the guard company at $30 to $100 an exam. Not all guard companies in Houston require it. Hiring standards at most firms are minimal, expressed by the litany I heard one afternoon in an interviewing office: “Are you eighteen, a citizen, do you have a car, a telephone, a clear police record, and a pair of black shoes?” And if my experience is typical, most security companies in Houston make no attempt to verify the information applicants give them.

To test the notion that some security companies are as good as their names, I applied at the Houston office of Pinkerton’s, the company whose name is legend and to which the Alley Theatre turned for protection after the killing of Mrs. Siff. Allan Pinkerton, the firm’s founder, was chief intelligence officer to Abe Lincoln and the Union Army; more venerable credentials don’t exist. The receptionist at the Houston office told me that before I could be hired, she would have to verify my background claims. She said I’d hear from her on the following Tuesday.

As she had promised she did make a call, to the last employer listed on my form. I claimed to have worked for a small West Texas implement company owned and run by an old friend (who knew I was using his name) and his brother (who knew nothing of my shenanigans). When the receptionist called, the brother answered. He said that I had never worked at the shop but promised to check with his brother, my friend and coconspirator. The receptionist left her number, and two or three hours later my friend called to say that yes, he knew me well, and yes, I was a great fellow.

Early Tuesday morning, the Pinkerton agency called the home telephone number I had listed on my application, a number that rings in Texas Monthly’s Houston office. “Texas Monthly,” a colleague answered. The voice on the other end of the line asked for me. “You must have a wrong number,” my colleague advised, now alert to his mistake. In a few minutes the phone rang again. This time he answered with a simple “Hello.” He told the caller I wasn’t in and took a message: I should call Pinkerton’s as soon as possible. Half an hour later I called and was summoned to the office to suit out in guard clothes. The next day someone from the agency telephoned to give me an assignment. Once again, a colleague answered, “Texas Monthly,” and once again, the farce was replayed. Pinkerton’s did not catch on to my act.

Pinkerton’s was careless with my application in other ways. For example, I listed Texas Monthly’s office as my home address, a location some ten blocks from the Pinkerton office. A simple city directory check of the address would have told the world’s oldest detective firm that I was spying on it. But the Pinkerton agency’s caution was unparalleled. The company made one phone call to check on my claims about previous employment; none of the other firms made any. My hiring by Pinkerton’s, however, may have been a Pyrrhic victory. I was put into a training slot; for thirty days, the company continues to make inquiries into the backgrounds of new employees.

The private security industry is booming in Texas. Statewide population and crime are increasing faster than municipal police forces. In Houston, the growth of the city police corps has just barely kept up with the area’s population increase in the last decade, and the crime rate has soared. In 1976 there were some 250 security contractors in Houston. Today there are twice as many. In 1973 the Labor Department counted 388 guards on payrolls in Houston. Today there are 10,000. Ten years ago Houston’s police officers outnumbered private guards by a ratio of more than four to one. Today there are three security guards for every cop.

In the days of one-story Texas, homes and offices faced onto public streets and backed onto public alleyways. Police officers on traffic patrol kept an eye out for comings, goings, and suspicious circumstances. Today, our cities are pocked with towering offices, apartment buildings, and shopping malls, huge expanses of private property that extend beyond the scope of the passing patrolman’s eye—and sometimes his orders. In these areas, comings, goings, and suspicious circumstances are not the concern of municipal authorities until after crimes are reported; the status of a policeman on private property is ordinarily that of invited guest. Private security guards are the first, and sometimes the only, agents of order.

They are not peace officers: they have only citizen’s arrest authority. Though citizen’s powers can be potent—in Texas, anybody can arrest someone he sees committing a felony or “an offense against the public peace”—few guards are aware of their powers. The law sets no educational or training requirements for ordinary guards, and if my experience is indicative, even the best companies give new employees only cursory orientations.

Of the companies that hired me, only Pinkerton’s provided any classroom training for newcomers. According to that company’s rule books, new employees are to be given four hours of instruction, to sign forms saying the instruction lasted four hours, and to be paid for attendance. The training session I went to lasted only ninety minutes, though I was paid for four hours. The instructor, a Pinkerton’s executive who has since left the company, explained work rules, vacation and promotion policies, and the importance of fire prevention. After his very professional lecture, he gave me my first order: to trim my moustache and get rid of my cowboy boots. My appearance, he said, was unprofessional.

Guard training programs are rare because training increases cost. In many cases the people who contract for guards don’t really care about the quality of guard services because they aren’t the people who are to be protected. Many plant, building, and mall managers pick guard companies with only cost considerations in mind. “I hire guards as an excuse,” one Houston property manager told me. “If something should happen to one of my tenants, like a rape or a burglary, I could be liable unless I provide security. So, like everybody else, I hire the cheapest guards I can find.” Generally speaking, penny-pinching clients get what they pay for: scarecrow cops.

There is, however, an elite of security guards: the corps of commissioned officers. They represent only a sixth of the total guard force. Commissioned officers are graduates of a state-approved course on criminal law and pistol handling. Twenty-some schools in Houston, most of them in-house company operations, train security guards for commissioning. During my time in the city, I attended one of these schools with twenty other guards. I found that though schooling gave us a better understanding of our jobs, it did not make us into the competent guards some clients expect to hire.

The most critical failure of the schools is in firearms training. The schools were set up to enable guards to carry handguns, yet their students are given only a day’s worth of revolver instruction and to qualify for duty must fire only thirty rounds at a motionless, man-size target fifty feet away. What the schools teach amounts to pistol safety, not marksmanship, which like any manual or athletic skill requires long and frequent practice. A commissioned guard is not likely to abuse or play with his pistol, because the schools impart an awareness of danger, but neither is he likely to defend himself or his client very well. Armed self-defense is probably vital to anyone who works in uniform; last December two unarmed Houston guards were shot to death on their jobs at an industrial site.

Commissioning does not ensure that guards are competent to make arrests, either. Most companies give their commission candidates the minimum instruction required by law: thirty classroom hours. By contrast, municipal police officers in Texas must receive 320 classroom hours of training, and in Houston, local authorities have doubled that requirement.

The illusion of authority is the stock-in-trade of guard companies. That is why guards are dressed not in industrial uniforms but in law enforcement look-alike outfits. Uniforms have a psychological effect, and to test how people respond to someone who looks like a cop, I wandered about Houston and Austin in a uniform I put together for a guard company that existed only in my imagination. My getup included a pistol holstered to a patent leather gun belt, a garrison cap, and metal badges, all purchased from retail suppliers. (Uniform regalia of all kinds is freely sold to the public. From one supplier I even bought a billfold badge made for Austin police patrolmen.) Though it is against the law for guards to carry handguns unless they are on duty or on their way to or from work, I paid a ticket at a police station, bought a money order in a bank, and had supper in a bar in full uniform. No one said anything about my pistol. (Had anyone taken it from me, he would have found that it was as much a dummy as my security company.) The privileges accorded me while in uniform included—oh, dream of dreams!—free admission to a freak show at a carnival in the Astrodome. My conclusion from these rovings in costume was that so long as lawmen are respected or feared, uniforms and badges will elicit deference. The trouble is, criminals already know this. Over the past two years, the Houston Police Department has received some twenty rape complaints in which the victims, mainly juveniles, say that they were attacked by men wearing what looked like police uniforms; two of the complaints resulted in arrests, both of security guards who had gained the confidence of their alleged victims by looking like cops.

Responsibility for the quality of guard services falls on the shoulders of both private security firms and the state government. It is they who must see that our guards are not criminals in sheep’s clothing. Security company operators say that they would check on the conviction records of guards and applicants were their hands not tied by the federal Privacy Act of 1974. The complaint is justified. By making it illegal for private companies and individuals to tap computerized crime information files, privacy legislation has made it nearly impossible for employers to check out the people they hire. The Privacy Act and parallel state regulations have put our judicial theory at odds with its practice. Crimes are in theory committed not against the police but against the people, the citizenry. Criminals are tried, sentenced, and imprisoned not in the name of the police but in the name of the people. Yet since the passage of the Privacy Act, the people no longer have access to centralized public records of crimes committed against them. Only police agencies do.

Arrest and conviction records are entered into the National Crime Information Center’s computerized data bank. The Privacy Act prohibits public release of NCIC reports, though it does not close off all access to criminal records. Reporters, employers, and nosy neighbors—the people—cannot tap the NCIC system, but courthouse records remain open to all lookers. The trouble is, no employer can afford to check the records in all the nation’s courthouses to determine if an applicant has been convicted of some crime, somewhere, sometime. For all practical purposes, a person’s record is today a secret known only to him and to the police.

There is one exemption, a crack in privacy law regulations through which Texas security companies can attempt to get a glimpse of the past deeds of their employees. A guard can carry a pistol only after having been commissioned by the Texas Board of Private Investigators and Private Security Agencies (PIPSA). Commissioning requires, in addition to the schooling already mentioned, a check by PIPSA of computerized crime files. The check costs $15. One inadequacy in this procedure, however, is the incompleteness of the NCIC crime files—entry of data is voluntary and only eight states (Texas is one) contribute to the system. If in its search PIPSA does discover that the employee has been arrested, all it can do is notify the employee and the employer of the date and place of arrest and ask for an explanation. Even if the employee was arrested for murder, PIPSA cannot reveal the charge.

The PIPSA records checks can be run even on guards whom companies don’t plan to arm, and the check would be widely used, perhaps, if it were practical. Even PIPSA’s “expedited criminal history check,” which costs an extra $4, takes two to four weeks to procure, and because of the Privacy Act, PIPSA can run checks only on people who have already been hired as guards, not on job applicants. This means that checks are run after guards are already on their jobs, in uniform—if companies choose to run them at all. For reasons endemic to the industry, security firms can’t expect that guards will still be on the payroll two to four weeks after hiring, when PIPSA reports come through.

Federal and Texas experts estimate the turnover in the private security industry at about 200 per cent annually. The most promising young recruits who put on security guard uniforms do not keep them for long because wages in the industry are low and benefits almost nonexistent. One reason is that the security industry is divided into competing sectors—one public, one private—and the public sector’s costs are subsidized by the taxpayers. Most of Houston’s 3200 uniformed police officers moonlight as guards while wearing their cloak of office, and so do most of Harris County’s 1200 deputy and reserve constables. These guards are recruited, uniformed, equipped, and sometimes dispatched at taxpayers’ expense, and they are far better trained than private guards. Competition from the police forces sets a ceiling on fees for security services. At present, the wage scale for off-duty Houston policemen begins at $13 an hour; for the constabulary, at $10 to $12 an hour. To ensure a clientele for itself, the private security industry must underbid its subsidized competitors. It does: the going rate for guard service in Houston is $7 to $9 an hour.

Companies in turn pay their guards starting wages of $4.50 to $5.50 an hour, and there is little chance for salary advancement. As a group, guards earn about a dollar an hour more than janitors do, and neither group is paid what can be called a living wage. Older, infirm, and immigrant men become janitors in Houston. Young men whose educational backgrounds are weak become guards, and they usually upgrade their occupations when the opportunity presents itself. Reducing the size of the labor pool by raising job qualifications would cause wages to rise, but currently the private industry has no reason to make that move.

PIPSA does not have authority to set wages for the industry, nor can it speed up its criminal records check without approval and funding from the Legislature. In security affairs, the Legislature has acted as the handmaiden of private companies. It created PIPSA in 1969 at the request of security chain operators, who wanted a statewide licensing procedure to replace the patchwork of local ordinances then in effect. From its birth until 1975, PIPSA did little more than charter private firms and take complaints against them. But in that year it was given a new power—again at the industry’s request. The penal code that had gone into effect a year earlier made pistol packing an offense for most purposes, and security guards—even armored car drivers—had not been exempted from the new code’s prohibitions. The industry asked for and got a law enabling PIPSA to commission guards to carry handguns.

PIPSA’s records clearance is slow, despite crime records computerization, because the agency is underequipped: it does not have its own terminals. It shifts its work onto the Department of Public Safety. PIPSA is also understaffed. It has 23 employees, who are charged with keeping tabs on 2000 companies and 15,000 commissioned guards across the state. It has only two investigators in Houston. PIPSA has another problem, too: it has no authority over the state’s 90,000 noncommissioned guards. No law requires guards who do not carry pistols to be registered with PIPSA.

New guard outrages may continue to be reported in our newspapers every week, but there will be fewer of them if—and only if—our Legislature will reform the security industry. It can do so in several ways.

Guard companies should be required to verify applicants’ employment references and to obtain PIPSA clearances on all employees. PIPSA—currently a board for the regulation of a business, not an agency with policing powers—should become an arm of the Department of Public Safety, because the DPS, as a law enforcement agency, is allowed to run computer checks on the criminal records of job applicants. Or PIPSA should be granted the funds and staffing necessary to speed up its processing of clearance requests; the expense could be recouped from licensing and commissioning fees. The Legislature should either prohibit police moonlighting or, to give the private security industry room for both profits and improvement, set higher minimum rates for off-duty work by lawmen in uniform. To make it more difficult for guards to pose as lawmen or to be mistaken for real cops, guards should be required to replace their metal badges with cloth patches.

These or similar proposals are not new. In 1976 the now defunct federal Law Enforcement Assistance Administration issued a thorough, 580-page study of the security industry nationwide, citing the dangers of the situation that exists today. The LEAA’s proposals are known throughout the industry, and no doubt in our Legislature as well: during its last two sessions, bills that would have implemented them died in committee.

Improvements in private security systems will not be free. Weeding out criminals from security agencies will increase the cost of guard services by $1 to $2 an hour. The expense will be passed on to consumers—the you and me who want protection. I believe that we are ready, and have always been ready, to pay for reliable security; few other services are worth as much to our peace of mind. Had the Legislature voted to require the screening of all guards when the proposal was first made, we would all be working, shopping, and sleeping with a greater sense of tranquility—and Iris Siff would be with us today.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Houston

- Austin