This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I can’t talk about it, bruddah,” Huey Meaux said to me. The man who was once the single most important figure in popular music in Texas was sitting on an aluminum stool in the squalid fifth-floor visiting room of the Harris County jail. This was his first interview since he was arrested—charged with child pornography, having sex with minors, and cocaine possession—and then recaptured after jumping bail and spending a month on the lam.

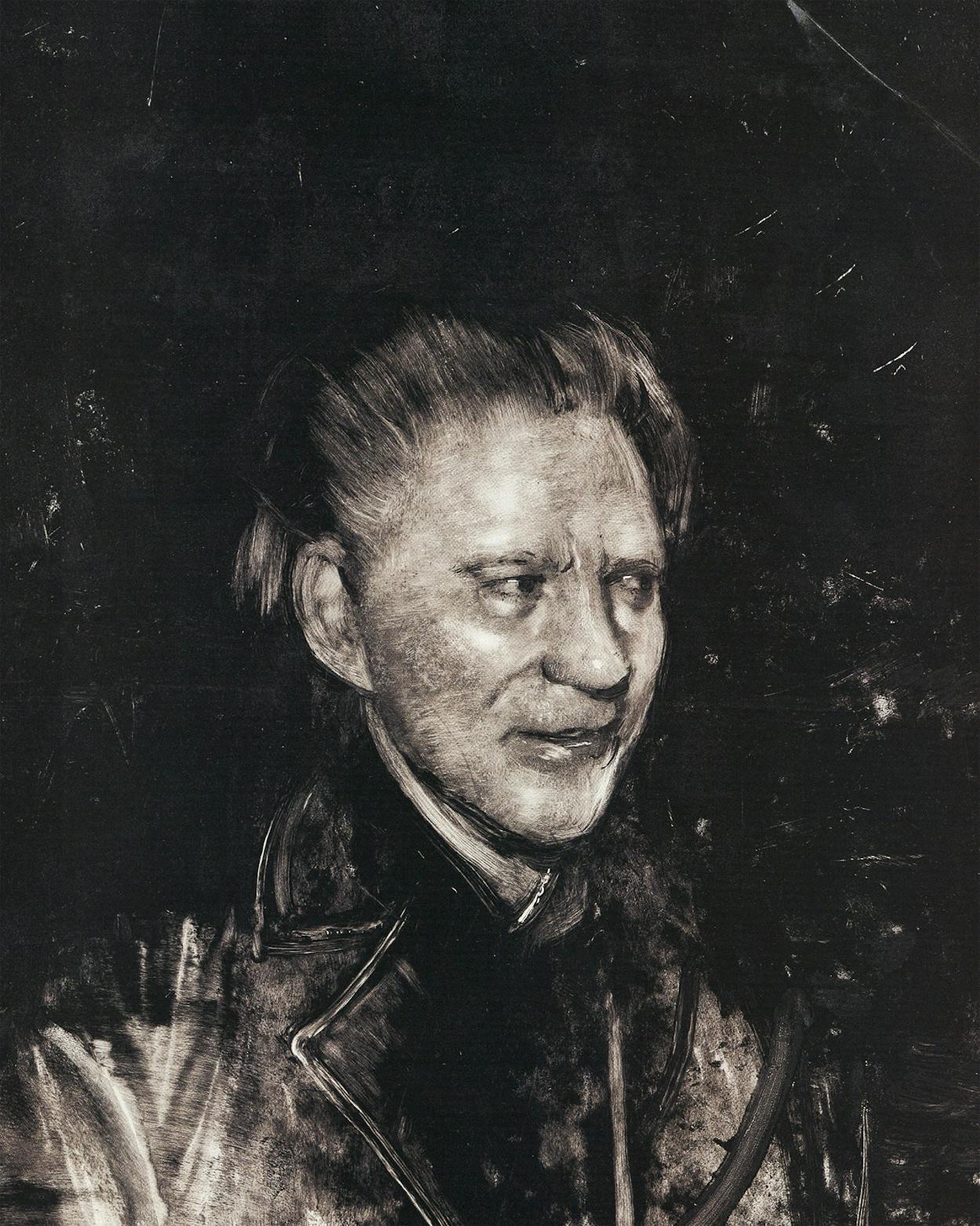

The 67-year-old Meaux winked at me and gestured at the round metal speakerphone as if it were bugged. “I just can’t say anything right now, bruddah,” he said. His voice was subdued, though still laced with a thick Cajun accent. But the fear in his eyes, the tentative glances, the snow-white hair and eyebrows (which he used to dye dark brown), the scraggly beard—this was not the colorful, larger-than-life producer of dozens of Top Ten hits I had known for 22 years. This was the Huey Purvis Meaux I’d been reading about in the newspapers and had seen on television. The one with the sordid double life he had hidden from almost everyone.

“If I’d known you were coming by, I would’ve cleaned up,” he said, scratching his chin and cracking a slight smile.

I tried small talk. Had he heard any young talent in the joint?

“No, man, they’ve got me locked up in solitary under protective custody,” he replied. It was for his own safety. No one likes a child pornographer, even in jail.

Solitary was rough. “No TV, no books, no nothing, except a Bible. I’m studying the Bible. I figure it’s something I could learn a few things about.” They all come around sooner or later, I thought.

When I mentioned his son, Ben, who had first alerted the Houston police to his father’s drug use and sexual activities, Meaux shook his head. “I can’t even say his name.”

He looked and acted so pathetic that I hardly recognized him. He slowly began rising from the stool. “Time’s about up and I don’t want to give them a reason to come down on me,” he said. “Come see me when I get to Huntsville.”

If I wanted to find out what happened to Huey P. Meaux, I’d have to look somewhere else.

Huey’s Playroom

The man who called himself the Crazy Cajun was vulgar, brash, and always outrageous. His “thing,” he was quick to let anyone around him know, was “young chicks.” The drugs the police found in his office weren’t a surprise; he was no stranger to illicit substances. But in the world of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, his roguish behavior only enhanced his legend as a musical wizard—the man behind more hits made in Texas and Louisiana in the last half of the twentieth century than anyone else. It was quite an accomplishment for a former barber from Winnie, Texas, who made the transition from “cutting hair to cutting hits,” as he used to tell me, with little education or musical training. But he had a gift for matching a voice with a song and for selling the finished product. Many times I sat and listened to him tell a few hours’ worth of tales about working with Doug Sahm, Lightnin’ Hopkins, George Jones, Clifton Chenier, T-Bone Walker, Dr. John, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Freddy Fender, and Jerry Lee Lewis, and I always came away convinced he was a bigger star than any of them.

But kiddie porn? Had Meaux crossed the line from rake to monster behind the immunity of stardom? Meaux’s arrest and the events that followed made for the most sensational crime story of the year in Houston, and his image was splashed on the front page and all over the nightly news. Two friends—who were also Huey’s friends—and I tried to sort it out. No one had any idea. Or did we? Huey was up-front about his hedonism, but had we unwittingly encouraged or overlooked behavior that was clearly against the law and damaging to his victims? We’d laughed over the memory of Huey introducing a young girl on his arm as his niece, only to have to ask her to “tell them your name, cher.” But I also remember that as far back as 1978, Huey had taken photographs of his longtime live-in girlfriend’s eight- and nine-year-old daughters playing naked in the oversized bathtub in their home. After he took the film in to be processed, the developer notified the police, who came to the house and talked with the children’s mother. Meaux brushed off the incident, saying there was nothing malicious about the photos. Now I wonder.

Not coincidentally, the door to Meaux’s secret life was flung open by one of those girls in the bathtub, Shannon McDowell Brasher, now 26. In mid-January, Brasher told Houston police officers that Meaux had sexually abused her from the time she was 9 until she was 25. Many of those episodes, she said, were videotaped, and she knew where the police could find the tapes. “When she said, ‘My dad owns a recording studio,’ I knew right away who she was talking about,” said Officer Dwayne Wright of the Juvenile Sex Crimes unit of the Houston Police Department. Almost five months earlier, Wright had heard a similar complaint lodged by Ben Meaux, Huey’s 15-year-old adopted son. Ben had said that his father was messed up on cocaine and had been fooling around with girls who were Ben’s age. Ben promised Wright he would bring him a videotape with the incriminating evidence, but he never returned. Wright, a fourteen-year veteran of the police department, guessed that Ben got cold feet, as often happens, and the case was placed in the inactive file until Brasher made her complaint (her lawyers insist that though she and Ben grew up together, she didn’t know he had already gone to the authorities). Shannon’s sister, 24-year-old Stacy McDowell, told the police that she had been abused by Huey until the age of 12, when her mother and Huey split up. With her corroboration of Shannon’s story, Wright got a search warrant for Sugar Hill Recording Studios and an arrest warrant to be used if incriminating evidence was found.

Police officers detained Meaux on the morning of January 26, pulling him over as he was driving away from his house in a 1984 Mercedes. Wright told him that he had a warrant to search Sugar Hill for child pornography and cocaine.

“I don’t own the place,” Huey replied before going silent for the rest of the drive to the studio in southeast Houston behind Produce Row. Leaving a shaking Meaux handcuffed in the back seat of a police cruiser, ten officers from the southeast narcotics unit burst into the Sugar Hill complex, where Meaux leased office space, and put guns to the heads of studio engineers, musicians, and hangers-on.

“We scared them to death,” Wright admitted.

That was putting it mildly. Record producer David Thompson arrived at Sugar Hill fifteen minutes late for a recording session. “I was in a rush and noticed the parking lot was full of cars,” Thompson said. “One was a police car. I thought Joe Pyland, the cop who used to work the beat, might have dropped in. As I walked past the police car, I heard someone.”

“Hey, bruddah Dave!”

Thompson saw a visibly frightened Meaux in the patrol car.

“What’s the deal?” Thompson asked him.

“Awww, they busted me, man.”

“What for?” Thompson asked.

“Aw, that porno stuff,” Meaux said.

“What?” Thompson asked again.

“That porno stuff.”

They were interrupted by a uniformed officer, who frisked Thompson and escorted him into the lobby, where chief engineer Andy Bradley and other studio personnel had been sequestered. Bradley told Thompson he didn’t know what was going on.

Then an officer came into the room. “We found it,” she said. “Drugs and child pornography. Thousands of pictures of child pornography.” The evidence was so disgusting that she said, “If I was the mother of one of those children, I’d skip the trial process.” Then she looked at the group detained in the lobby and derisively spat out, “And none of you knew what was going on.”

It was true. They didn’t. Huey carried on his depraved activities in an interior room of his office, hidden behind double doors. Shannon Brasher, however, knew the layout of his playroom all too well. “She told us what we’d find,” Wright said. “The painting of the señorita, the mirrors on the wall, hundreds and hundreds of photos, a doctor’s examining table with gynecological stirrups, an icebox, two small gray safes, magazines, and videos stacked on the shelves. The whole place looked as if it had been ransacked. He had telephone notes from 1984 on his desk, which later proved to be useful to us. There was cocaine on the floor and the doctor’s examining table. Most of it was on a plate with a rolled up ten-dollar bill and razor blade.” A box in one of the safes had small packages of cheap jewelry. The other safe had eight audio cassettes. There were approximately 10,000 photographs of all kinds—at least 1,500 of them were pornographic.

“He had cataloged the photos with dates and everything,” Wright said. “We went through photos and found girls who we later learned were twelve to sixteen years old, and others seventeen to twenty-one. We found thirteen rolls of undeveloped film in a bag. There were kids eight, nine, ten years old.”

Wright went out to the police car and informed Meaux that he was under arrest. “I told him some of the girls were under seventeen years of age.”

“Some might be, some may not,” Meaux said.

Meaux was charged with possession of child pornography and possession of a controlled substance (fifteen grams of cocaine). Thanks to Huey’s filing system, Shannon was able to identify one young girl who was willing to testify that Meaux had sexually assaulted her. After several other victims were contacted in the days following his arrest, he was charged with two counts of sexual assault of a minor. In the two years the forty-year-old Wright had been working juvenile sex crimes at the Houston Police Department—averaging 325 juvenile sex-crime cases a year—this was the biggest he had seen. “It’s the old ‘drugs, sex, and rock and roll.’ That’s what you’ve got here,” Wright told me. “But there’s another thing that motivates me: the girl who came forward. I saw her in a video and thought she was lost. Huey didn’t want to listen to her. He just wanted her to take her clothes off. Then I met her. She’s got her life together. To see that someone can come away from him motivates me, because wherever he goes, he’s going to do that again.”

A few days after the additional charges were made, a team of attorneys including high-profile criminal defense lawyer Dick DeGuerin and plaintiff’s attorney Percy “Wayne” Isgitt filed a $10 million civil suit against Meaux on behalf of Brasher, accusing him of sexually abusing her as a child. Brasher may yet be added to the criminal case because some of the alleged assaults against her occurred when she was sixteen—still within the statute of limitations for the sexual assault of a minor. Then a divorce suit was filed by Hilda Meaux, Huey’s wife of 42 years, a woman I had never heard of. On top of all that was a guardianship battle for Ben Meaux.

Facing the possibility of a long prison sentence and losing all his money, Meaux failed to show up the week after his arrest to be fitted for an electronic monitor. He had skipped town in the company of a shadowy associate named Jim Davis, forfeiting $130,000 in bail bonds. Davis and Huey had met in federal prison years ago. “Jim was the butcher in ‘college,’ ” Huey had told others, “he always got me the best cuts of meat.” Davis had shown up last fall. By the time of Meaux’s arrest, he was living with him and representing himself as Meaux’s business adviser.

Bounty hunters knew that wherever Davis was, Huey was likely to be close by. They trailed Davis from Las Vegas to Dallas and then to El Paso and Juárez, Mexico. By then, they had picked up Meaux’s scent in Juárez, and by tracing Meaux’s credit card billings, they were monitoring his and Davis’ movements to different hotels around the city. When Davis came across the border into El Paso, FBI agents involved in the search confronted him with the prospect of doing time for aiding and abetting a fugitive. Davis told them Meaux was camped out in a suite at the Juárez Holiday Inn. Twenty-nine days after he’d fled, Meaux was apprehended without incident. One of the bounty hunters told me that Huey’s bags were packed as if he had been preparing to move again.

The one revealing statement Meaux offered me when I spoke with him in jail came when I asked him if I should talk to Jim Davis.

“If you can find him, bruddah,” he said. “They tell me he was the one who gave me up, but I don’t believe he snitched on me.” In this instance, though, the Crazy Cajun was mistaken.

Cutting Hits

I met Huey in the early seventies after I had moved back home to write about Texas music. Naturally Huey became an invaluable resource. We spent a lot of time together over the years, and I wrote several articles about him, glorifying his seat-of-the-pants hustling, his wit, and his astute observations on the music business. He was one of the last links to the time when records were sold out of the trunks of cars and music was popular because it sounded good, not because it fit a marketing niche. But after his arrest, it became clear to me that there was much about the man I didn’t know. I felt like I should have known who Jim Davis was, that a Hilda Meaux really did exist. I was surprised to hear Huey described as a cocaine addict. And, of course, I was stunned by the revelations of his perversion. He once showed me a hard-core porno tape. And he never hid the fact that in the late sixties he spent three years in prison for conspiracy to violate the Mann Act (also known as the white slave traffic act)—specifically, for transporting an underage female across state lines to a disc jockey convention in Nashville. He had always maintained that he didn’t know the girl was a minor but admitted she was taken along to entertain the deejays with sexual favors—“a favor for a favor” was his business credo. Meaux said that the whole episode was a setup and that he took the fall because he wouldn’t incriminate others in the record “bidness,” as he called it. Meaux always spoke with pride about his pardon by President Jimmy Carter in 1977, though in retrospect it probably only encouraged him to resume the behavior that led to his arrest.

Huey Meaux grew up outside of Kaplan, Louisiana, a small community surrounded by rice fields near Lafayette. His parents and siblings were poor sharecroppers who spoke mainly Cajun French, worked hard in the fields all week, and played harder on Saturday night, when Creoles and Cajuns would push back the furniture in a house, get roaring drunk, and dance to a band all night long.

“Back in them days, my dad worked for the man—picked cotton, hoed, grew rice, shucked it, and harvested it,” he told me one time. “We had four shotgun houses, two black families, two white families. Music was a release. If somebody didn’t get cut up and beat the shit out of someone, the dance was considered bad. I was raised that way.”

He moved with his family to Winnie at the age of twelve, part of the Cajun migration west across the Sabine River to greener rice fields and better jobs. His father, Stanislaus Meaux (known to all as Pappy Te-Tan), played accordion and fronted a group with teenaged Huey as the drummer. “I wasn’t worth a damn,” Huey told me once, but the excitement of being in a band stayed with him. In his twenties, he cut hair at the barber shop by day. “A barber is like a bartender, he knows who is screwing whose wife, when, and what time. I dug all that because I was part of something,” he said. After hours, he was a disc jockey, hosting teen hops in Beaumont and promoting dances all over the Golden Triangle.

His colleagues on the local music scene included singer George Jones, pianist Moon Mullican, and disc jockey J. P. Richardson, a.k.a. the Big Bopper. (“I was riding with him in the back seat of a car from Port Arthur to the studio in Houston when he wrote the lyrics for the B side of a novelty song he was cutting called ‘Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor.’ He called the B side ‘Chantilly Lace,’ ” Huey told me back in the seventies.) A local promoter and record producer named Bill Hall taught Meaux the nuances of the business of music, mainly by never paying Meaux what he was owed. “That was my college education in the bidness. I didn’t think people were supposed to get paid for having fun. So Hall would take my records, put his name on them, and take them to the record companies. When we’d go to Nashville, he’d tell me to keep my mouth shut. He said they’d laugh at my accent up there. And I believed him,” Huey said.

In 1959 Meaux produced the first hit with his name on it, “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do,” a maudlin lament by Jivin’ Gene, as Meaux had rechristened Gene Bourgeois. The song’s hook, he liked to tell people, was the vocal’s echo effect, which was accomplished by “sticking Gene back in the shitter, surrounded by all that porcelain.” Subsequent hits such as Barbara Lynn’s soul stirrer “You’ll Lose a Good Thing,” Joe Barry’s swinging “I’m a Fool to Care,” Rod Bernard’s “This Should Go on Forever,” T. K. Hulin’s “As You Pass Me By Graduation Night,” and Big Sambo and the Housewreckers’ histrionic “The Rains Came” were all expressions of teen sincerity tailor-made for belly rubbing on the dance floor. The sound was dubbed swamp pop in honor of the region the artists came from.

Meaux was on his way to becoming a one-stop hit factory; eventually he would own many labels and Sugar Hill Recording Studios and manage artists; he would publish his artists’ songs, collect their royalty checks, and promote their records to radio stations. The way Meaux told it, his first royalty check, $48,000 for Barbara Lynn’s “You’ll Lose a Good Thing,” attracted too much attention around Winnie. “Even today people think I made that money selling dope,” he told me years ago. “I never sold any dope in my life. Sold some whiskey before, took some dope, but never did sell none.” He shifted operations to Houston, where peers like Don Robey at Duke and Peacock Records and H. W. “Pappy” Daily at D Records were cutting and selling hits as if the town were Nashville and Memphis combined. Among such company, Huey was well known for his good ear and even better known for his promotional talents. “The song is number one. The singer is probably third or fourth,” he explained to me. “The song makes the singer and the producer. Promotion makes all of it. It’s up to the man behind the desk, spending money here and there, taking care of favors, just like you elect a president or governor.”

As a promoter, his most brilliant stroke was co-opting the British invasion of the early sixties by finding a Tex-Mex rock band from San Antonio, dubbing them the Sir Douglas Quintet, dressing them up in British mod outfits, and even releasing their record on the London label. The record was “She’s About a Mover,” which broke onto the Top Ten pop charts in 1965. Image was everything. “He used to make the married members of the band take off their wedding rings before going on stage,” recalled organist Augie Meyers. “He didn’t want to spoil the illusion.”

Thanks to Meaux’s relentless efforts, an all-Mexican San Antonio band called Sunny and the Sunliners broke the racial barrier on television’s American Bandstand by performing a bluesy version of Little Willie John’s “Talk to Me” in 1962. Soon after, Meaux had another hit—a slow and thoroughly teen rendering of Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome, I Could Cry” by a young white band from Rosenberg called the Triumphs, fronted by a pimple-faced kid named B. J. Thomas.

“The reason why I had so many hits was that around this part of the country, you’ve got a different kind of people every hundred miles—Czech, Mexican, Cajun, black,” Meaux said. The names came and went—Roy Head, Chuck Jackson, Ronnie Milsap, Mickey Gilley, Lowell Fulson, Joey Long, Doug Kershaw, Clifton Chenier, Big Mama Thornton, Johnny Copeland, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Archie Bell and the Drells, Tommy McLain, Cosimo Matassa, and Jerry Wexler—all of them made records or worked with Meaux at one time or another. For two generations of Gulf Coast rock and rollers—or any musicians from Baton Rouge to San Antonio—he was the pipeline to the big time.

But for every Dale and Grace topping the charts with perfect pop hits like “I’m Leaving It Up to You,” there were twenty failures. Meaux’s magic never worked for two talented young boys from Beaumont, Johnny and Edgar Winter, whom he recorded under the names “the Great Believers” and “Texas Guitar Slim.” “We’d put them on a local television show called Jive at Five, and their records would stop selling like you turn a light switch off,” Meaux said. “People would freak out, being as they was albinos.” He said he never got credit for his part in the discovery of ZZ Top and years later took great pleasure in suing the band and manager Bill Ham on behalf of Linden Hudson, a songwriter who was never paid or credited for a song the band recorded. Huey had a copy of the settlement check framed on his wall.

The flip side of his skills as a producer and a promoter was his willingness to take advantage of his artists. An artful con man, Meaux would mockingly warn his acts, “I wouldn’t sign that if I were you” at the contract table. Another time he said, “I like to keep my artists in the dark so their stars shine brighter.” The artists, hungry for fame and fortune, never balked—and many enjoyed long friendships with Meaux even though he took advantage of them. Gulfport, Mississippi, songwriter Jimmy Donley was a sentimental lyricist who sung in what Meaux called the heartbreak key. Donley sold compositions such as “Please Mr. Sandman,” “Hello! Remember Me,” and “I’m to Blame” to Meaux (and to Fats Domino, among others) for $50 apiece because he needed the money and figured he could always write another song. Even though Donley hardly profited from the relationship, he and Meaux remained close friends; Donley called him Papa. In the liner notes Meaux wrote for the Donley memorial album, Born to Be a Loser, he says that in 1963 Donley called him to thank him for all he’d done for him; 45 minutes later, Donley committed suicide.

Huey’s gift of gab made it possible to overlook the gray areas of his personality—the way he treated his artists, his open interest in young women, and his hedonism. The first time I walked into Sugar Hill Recording Studios, in 1974, two years after Meaux bought it, he regaled me for the entire day with the story behind each of the gold records, the publicity photographs, and other mementos hanging on the wall and cluttering the desk in his office. It was a history lesson about roots before the roots of rock were cool.

His showmanship peaked as the Crazy Cajun on his Friday night radio program on KPFT-FM. Huey didn’t just announce records, he went wild—stomping his feet to the music, whooping, singing, and yakking nonstop: “Give it to me good, Houston, unh, you sure betta b’lieve it. Come close to the radio and give your papa some sugar, sweet cher ami.” A good portion of the radio audience was “the men and women in white up in the TDC”—prisoners in the state system, mostly up in Huntsville. Huey read their letters, sent them dedications (“Release Me” was a popular request), and visited with their relatives in the studio.

One night when I was in the studio watching him do the show, he auditioned two new singles he’d just released on his Crazy Cajun label—“Country Ways,” by Alvin Crow and the Pleasant Valley Boys, from Austin; and “Before the Next Teardrop Falls,” by Freddy Fender, a fifties-era Tex-Mex rocker from San Benito [see Music: “Wasted Days,” TM, October 1995]. The Crow tune never went very far, but the Fender cut was Meaux’s biggest meal ticket of his career. Fender had a promising career interrupted by a stint in Angola State Prison in Louisiana for possession of two marijuana cigarettes in the early sixties. He had come to Meaux, citing the common bond of their experiences behind bars. The two had tried a variety of combinations, including Jamaican reggae sung in Spanish, to no avail until Meaux cajoled Fender into singing on top of an instrumental track recorded by an anonymous Nashville country band.

“Before the Next Teardrop Falls” was the unlikeliest country and pop hit of 1975, eventually reaching number one on Billboard’s Hot 100. The follow-up, a remake of Fender’s 1959 regional rock hit “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” went to number eight. Fender and Meaux had discovered a formula: recycle the swamp pop melodies into modern country music by replacing horn charts with steel guitar fills and female choruses. Meaux was Fender’s producer and manager, meaning he received a bigger cut than his artist. Freddy didn’t care because they were both getting rich with hits like “Secret Love,” “You’ll Lose a Good Thing,” “Living It Down,” and “Vaya Con Dios.” Freddy bought a house on Ocean Drive in Corpus Christi, where he parked his custom hot rods on the front lawn. Huey bought himself a Beatles-style shag wig and a Lincoln Continental, paid off his note on Sugar Hill Studios, and received major record company funding for his custom record label with a growing stable of acts.

By the end of the ride, in 1980, Fender was strung out on dope and booze and bankrupt with $10 million in debts. He was also accusing Meaux of taking advantage of him through unscrupulous contracts. Huey, who had previously specialized in one-hit wonders, was ready to sever the relationship too, blaming Freddy for squandering his earnings. In 1981 Meaux survived a bout with throat cancer. Save for one last novelty hit—Rockin’ Sidney Simien’s 1985 zydeco ditty “(Don’t Mess With) My Toot-Toot”—Huey more or less bailed out of the producer-manager-promoter realm and moved into music publishing. He augmented the Crazy Cajun song-publishing catalog by purchasing, among other tunes, Desi Arnaz’s signature song, “Babalu,” and a number of soul composer Isaac Hayes’ songs from the Memphis bank that assumed ownership of them after Hayes went bankrupt.

Family Affairs

The steady income from song royalties allowed Meaux the luxury of indulging himself, which he did in a most surprising way. Huey adopted a son. Ben Broussard was born on August 25, 1980 to the unwed daughter of one of Meaux’s business associates in Lafayette. Huey and his live-in girlfriend, Nancy McDowell, informally adopted the boy and began raising him, along with McDowell’s two daughters, Shannon and Stacy, in Kingwood, north of Houston. Ben was his pride and joy, Huey told everyone. All his riches were going to go to Ben.

But by 1984, Nancy was out of the picture, and Huey was determined to raise Ben by himself. He sold Sugar Hill in 1986 but continued to lease offices there, staying on as the studio’s producer emeritus, whose gold records helped attract business. But he didn’t arrive at work until after he had dropped Ben off at school, and he was usually gone by two-thirty every day so he could pick Ben up. A hit was no longer the challenge. Finding a housekeeper was. In deference to Ben, Meaux was finding it increasingly difficult to party with his young chicks, so he built his playroom in one of his offices, out of sight of prying eyes.

At home, it was another story. The trouble was that the Crazy Cajun was overly protective of Ben to the point of smothering him. As a teenager, Ben, who has a near-genius IQ, grew to resent Huey’s interference. Huey was old. He was a hypocrite. He showered Ben with material goods, but he couldn’t offer the compassion and tenderness of a parent. When they had their differences, both displayed stubborn streaks. By the time he was fourteen, Ben was complaining that he couldn’t bring his friends over to the house because of the way Dad talked around them, especially the girls. Huey must have found it hard to keep his other life secret. Once he ruined a video camera using a screwdriver to remove a tape starring one of his girlfriends because he feared Ben would discover it.

In November 1994 Huey was almost killed when he crashed his car into an embankment on a poorly marked highway detour near his old hometown of Winnie. His nose was split in two and stitches ran from his forehead to his stomach. When I spoke with him a month later, he was heavily medicated and complained that his head wasn’t right. But he said the wreck was nowhere near as bad as the troubles he’d been having with Ben. Because of their fighting, Meaux had sent him to Winnie to live with Meaux’s stepdaughter, Georgia LaPoint, who was the daughter of Hilda Meaux, Huey’s long-estranged wife. That didn’t work out, and neither did Ben’s eventual return to Huey’s house. The two kept fighting; after one heated argument, Ben pulled a knife on him. In September 1995 Meaux sent Ben to Utah for a two-month Outward Bound wilderness training camp, but before he went, a girl who remains unidentified shared with Ben her dark secret about Huey’s cocaine use and the sessions in his hidden back office, where Meaux had taken many young girls over the years to pose for videos and photos in exchange for coke, booze, jewelry, and money. The girl’s account of her time in the playroom stunned Ben, and he contacted the police. In December, after Ben returned from Outward Bound, Huey enrolled him at the Fenster School in Tucson, Arizona, a small, expensive private school for difficult children. It was recommended to him by Londa May, a school-placement counselor in Houston. Meaux paid the $18,000 annual tuition in advance.

A month later, Shannon Brasher went to the police and Meaux’s secret life was exposed. The hideaway functioned as a party room where, with drugs, jewelry, and perhaps the promise that he would make them stars, Huey enticed dozens—maybe even hundreds—of young girls to pose for him and allegedly to have sex. The pictures of nude children are sufficient to convict Meaux of possession of child pornography, a third-degree felony that carries a two-to-ten-year sentence. If Meaux was trading photographs across state lines, as Officer Wright suspected, the charges could be stepped up to a federal offense, with a maximum sentence of twenty years. If the prosecution proves that Meaux had direct sexual contact with a minor—there are many of the confiscated videos that do so, Officer Wright has indicated—Meaux could face life in prison.

Shannon Brasher’s $10 million civil suit alleges that Meaux molested her as early as the age of nine and that the abuse continued for sixteen years, until 1995. For six years, Huey lived with her and Stacy and their mother, Nancy. After Huey and Nancy spilt up in 1984, he still saw Shannon frequently. Many times he said he loved her, and he always referred to her as his daughter. Her picture was on his mantelpiece at home, and he encouraged her sibling relationship with Ben, often asking her to take Ben to the movies. When Huey took Ben to Disney World, he took along Shannon and her sister. Brasher had had her share of hard times, including a serious cocaine habit. People around Sugar Hill remembered her frequently showing up in a disoriented state and asking Meaux for money. He would cough up the dough and always blamed the guys she was dating and the bad crowd she ran with. He even paid for some of her drug rehab sessions (Brasher has been through eight rehabilitation programs). But Brasher tells a different story of her relationship with Meaux. She attributes her drug addiction and her dependence on Meaux to years of abuse by him. “He used his closeness to her as well as drugs later to literally get in her pants,” said her lawyer Dick DeGuerin. Nor were Shannon and her sister, Stacy, necessarily the only family members abused. Following Meaux’s arrest, 48-year-old Georgia LaPoint told the Houston Press that she had been fondled by Meaux between the ages of six and twelve. “He’s always been a very warped, perverted man,” she said. “And he still is.”

Ben hasn’t spoken to Huey since last September. Although Huey wrote Ben almost every day while he was at Outward Bound, Ben never replied. Officer Wright told me that when informed of his father’s arrest, the boy said he was glad. The kid had finally beaten the old man. But with his dad in jail, the guardianship of Ben became hotly contested.

After he was arrested, Meaux met bail bondsman Edd Blackwood to sign papers and discuss the situation. When Ben’s name came up, Meaux appeared to be in denial. “He’s mad at me. He won’t talk to me now,” he told Blackwood. Even though Huey knew that Ben had turned him in, his son’s welfare was still foremost on his mind. He instructed Guy “Buddy” Hopkins, a Montgomery County lawyer he’d known for thirty years, to take care of Ben’s guardianship and protect his inheritance. A Montgomery County court appointed Hopkins temporary guardian and appointed another attorney, Elizabeth Woodward, to represent Ben’s interests. Woodward went to see Ben in Tucson, along with Londa May, the counselor hired by Huey last summer.

According to Wright, the three met in an office at the school, and Woodward asked Ben to sign papers appointing Hopkins his temporary guardian. When May asked Ben to accompany her to the airport, supposedly to drop off Woodward, Ben became suspicious. Wright had told Ben to call him if anyone tried to get him to sign anything or to take him away. Ben went to another room to call Wright. Wright asked him if there was a way out. Ben said there was and ran down a hallway and hid while Wright called the Arizona police.

At the urging of Dick DeGuerin—who has since called the incident an attempted abduction and alleged that May, Woodward, and Hopkins, among others, were co-conspirators—Ben was brought back to Houston and placed in a shelter by Child Protective Services, where he visited with Shannon Brasher almost daily. He insisted that he didn’t want one of his father’s friends or lawyers as his guardian. He wanted Shannon. After six weeks at the shelter, Ben returned to school in Tucson while the court continued to search for an appropriate guardian. DeGuerin’s proposal that Brasher be named temporary guardian was turned down.

The legal dog pile shows no sign of ending. Obviously one of the issues in all the civil litigation is Meaux’s net worth, which was initially reported in the newspapers as $30 million. It is now thought to be between $2 million and $3 million. Hilda and Huey’s divorce is proceeding, and she is being considered for guardianship of Ben, who has no other family in Houston besides Shannon, Stacy, and their mother. The criminal trial is not expected to begin for several months.

The End of Innocence

In the history of rock and roll, the list of incidents involving older men and underage females is long, beginning with Chuck Berry, who served time for violating the Mann Act; wild man pianist Jerry Lee Lewis, who almost destroyed his career when he married his 13-year-old cousin; and Elvis Presley, whose future wife, Priscilla, moved into his Graceland mansion when she was 15. The twisted dynamic persists: More recently, Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones at 53 was briefly married to 14-year-old model Mandy Smith, and Eagles member Don Henley was inspired to write “Dirty Laundry” after a well-publicized incident involving illicit drugs and a female under the statutory minimum.

Sex, drugs, and rock and roll stood for an entire generation’s rebellion against the music and morals of the past. Back in the seventies, we were enjoying ourselves too much to notice that Huey was already in his forties. We all grew up eventually; Huey never did. Of all his friends in the music business, Jim Dickinson, summed it up best: “When you met Huey, you sensed something greasy and criminal about him. It was always there. Now we know what it is. The music and the sex were inseparable. He was still producing. He couldn’t let go. He was still at the studio, still auditioning in his own way.”

In early April I went back to Sugar Hill for a last look at the secret world of Huey Meaux. Papers were strewn all over the place. Snapshots were still tacked to the walls. A photograph of Ben was framed behind his desk. A gag license plate on a wall read “Of All My Relations, Sex Is Best.” The scene inside the playroom was chilling. I could see two jars of mannitol, a white powder diuretic frequently used to add bulk to cocaine; a bar with bottles of grain alcohol and cherry-flavored sloe gin on the top shelf; a happy face and a message scrawled in pen on the wall-size mirrors—“Shannon, Denise & Lorinda friends for life + after”; and a metal box containing empty bottles of Percodan, Tylenol 3, and Valium. Everywhere, there were piles and piles of photographs.

I had wanted to believe in Huey Meaux’s innocence. Now I felt repulsed. “Damn it,” I hissed through my teeth. I was damning Huey and damning myself for being conned. I walked into the light of day with the feeling that I couldn’t bear to see him. It was a sad conclusion to a fabled career and to a friendship. And it wouldn’t help to hear a song sung in the heartbreak key.

- More About:

- Music

- Music Business

- Longreads

- Houston