This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Shearn Moody, Jr., had been hiding out as usual, but when his Aunt Mary died in August 1986, he surfaced for her funeral—just long enough to bury both of them. Mary Moody Northen had been one of the richest women in America and, until the infirmities of old age laid her low, one of the most powerful. For more than three decades she had controlled the family fortune, which Shearn considered to be his birthright. Mary Moody Northen died of old age. Her nephew’s demise can be credited to greed.

Aunt Mary’s funeral would have done credit to a czarina. It was an echo of Galveston’s glorious aristocratic past, choreographed with 22 rented limousines, an honor guard of cadets, and an assortment of patricians and dignitaries that included the governor and the attorney general of Texas. Radio station KGBC broadcast the service live. Galvestonians who had never met the grande dame face to face wept in the streets.

As Shearn Moody sat that day in Trinity Episcopal Church, listening to the eulogy for his aunt, he was racked with paranoia. During the weeks that Aunt Mary lay dying, Shearn had believed that she was the target of a murder plot. In a letter to a local judge, he attributed her pneumonia to “forced-feeding of soup in the bathtub by her in-house staff. He had photographs taken of his aunt on her deathbed and demanded an autopsy when she finally succumbed. Shearn’s paranoia about his aunt was characteristically ludicrous—the poor woman was 94, so frail and feeble she couldn’t eat—but Shearn saw plots in every shadow and conspiracies in every flicker of light.

On this particular day there was some justification for his paranoia. After the service, selected family members and associates gathered at the Moody-owned Ramada Inn on Seawall Boulevard for the reading of the will. By tradition, the Moodys left their money to charitable foundations under family control rather than to each other directly. But maybe this time would be different. “My beloved Aunt Mary” Shearn called her, and he considered himself to be her favorite. So the reading of the will must have been a shock to Shearn. True to Moody form, Aunt Mary had left not one penny of her estate to him or any of the other Moodys. Adding salt to the wound, she provided that all her money go to her own foundation, one headed by outsiders and Shearn’s younger brother, Bobby. Shearn had been cut out.

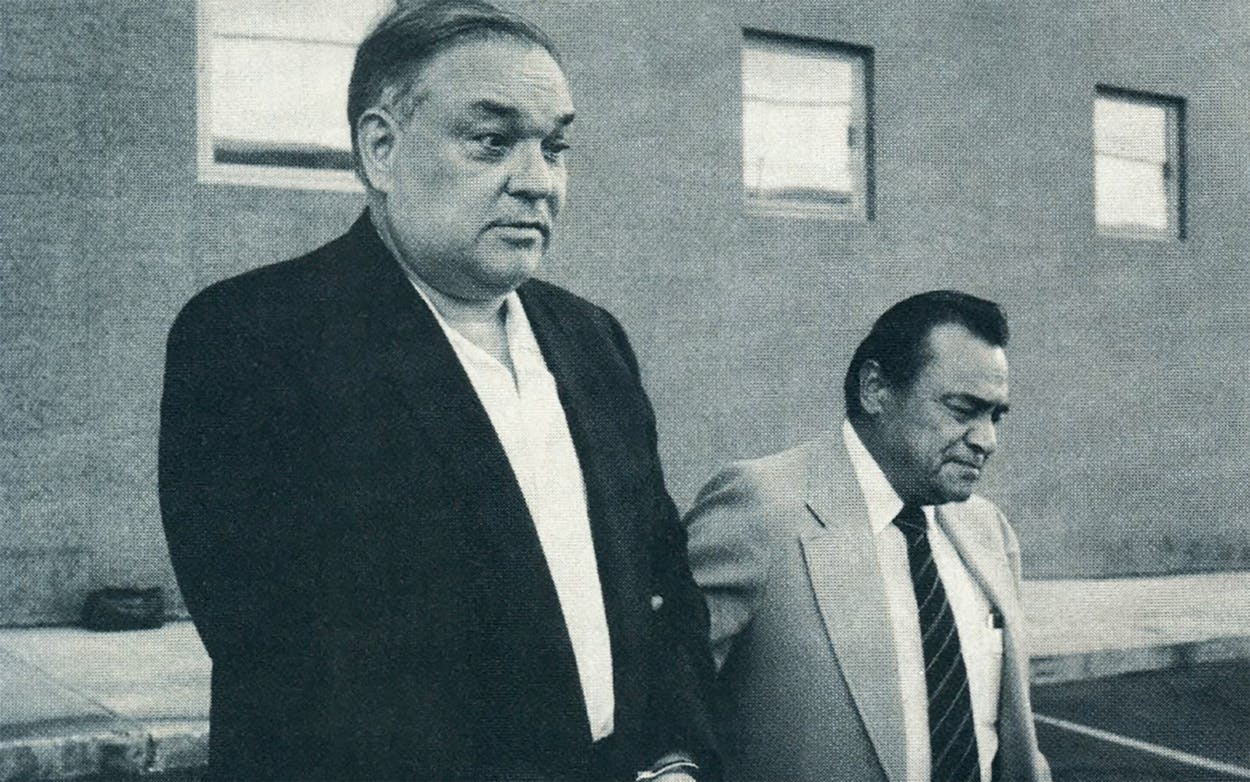

The will was Shearn’s second shock in as many hours. Earlier, as he was leaving the church, Shearn had been cornered by a United States marshal and slapped with a summons to appear before a grand jury in Houston. He had some serious questions to answer. The grand jury was investigating allegations that he had swindled millions of dollars from his family’s treasured Moody Foundation.

Shearn Moody, Jr., is a wreck. In his fifties now, he is overweight, hypertensive, bankrupt, and entangled in a web of legal complexities so dense and impenetrable that it may accompany him to the grave. In the last twenty years he has gone from being a man who had everything to being a man who apparently has nothing—he has lost his bank, his insurance company, his home, and now the guarantee of his freedom. He blames it all on politics, the ultimate conceit of many a wrongdoer. The Securities and Exchange Commission grabbed his bank in 1972, not because it disagreed with Shearn’s politics but because it discovered that he was selling unregistered certificates of deposit; his insurance company folded when authorities determined that it was insolvent because Shearn had overvalued the company’s assets; his six-hundred-acre ranch home is tied up in bankruptcy proceedings. Shearn is personally liable for $12 million in damages and interest resulting from a scheme to defraud his insurance company’s shareholders. Now Shearn faces two indictments, totaling 41 counts, in addition to a to a civil racketeering lawsuit. The indictments charge that he swindled between $2 million and $3 million from the Moody Foundation and concealed assets from bankruptcy trustees. The first of his two federal criminal trials was scheduled for July; the second is set for September. According to the indictments, Shearn used his position on the foundation board to funnel grants to a network of suspicious charities and con men who cloaked their true intentions in the robes of right-wing crusaders. How could Shearn have believed his scam would go undetected? And why did it go undetected for a year? The answers have a lot to do with the man himself and with the family that provided the wealth that has become Shearn’s undoing.

Awash in a Sea of Money

The Moody Foundation is the legacy of Shearn’s grandfather—Mary Moody Northen’s father—Galveston financier W. L. Moody, Jr. The old man, as he was called, was a legendary tyrant and skinflint who cared so dearly for his fortune that he placed it out of reach of his heirs. In a sense, Shearn is the extension of his grandfather’s karmic evolution but with a key ingredient missing: He inherited the old man’s greed and mean-spiritedness but not his gift for making money. Galvestonians refer to Shearn as the alchemist and joke about his ability to change gold into manure.

Shearn’s composition of character is a dangerous mix—all that ambition, unsupported by talent or any trace of principle. It is as though he were born with a part missing, as though he were awash in a turbulent sea of money without a gyrostabilizer. Shearn has been accused of trying to hire a hit man to blow the legs off a former associate who blew the whistle on Shearn’s activities; of devising a sting operation in an attempt to compromise a hostile insurance commissioner; and even of trying to bug the chambers of the Supreme Court of the United States. Normal restraints of law, ethics, and fair play never seem to have held back Shearn Moody.

While the sordid details of Shearn’s thuggery may have been the work of his hirelings, the central direction of events was the result of his thirty-year obsession with regaining control of the family fortune. When Aunt Mary’s health failed in the early eighties, control of her father’s foundation fell into the hands of Shearn and Bobby. Shearn apparently made the most of the opportunity. The scheme to drain millions from the foundation may turn out to be the ultimate expression of his disdain for everyone except himself. If Shearn is convicted, he will be revealed as a man who would stop at nothing—not even looting his family’s most sacred trust—to get what he wants. Shearn Moody, Jr., is more than just another rich guy who tried to beat the system; he qualifies to be called the sleaziest man in Texas.

Legacy of Greed

Despite the millions of dollars donated in their name to charity, the Moodys of Galveston are not renowned for their generosity or public spirit. During the final twelve years of the old man’s life—from 1942 to 1954—when he personally ran the foundation, its single significant charitable contribution was a $242,000 grant to a cerebral palsy home.

If it hadn’t been for Aunt Mary, the Moody fortune might still be moldering in the bank. She was far and away the most benevolent of the Moodys, responsible for building Moody libraries, dormitories, theaters, and field houses on college campuses all over Texas. The person actually responsible for changing the foundation’s philosophy was a former sociologist named Edward Protz, who served as the foundation’s grants coordinator from 1969 until Shearn and Bobby got him ousted in 1982.

Until Protz’s arrival, the foundation had given mostly brick-and-mortar grants, constructing buildings that would have gotten built anyway. Under its charter, the foundation is supposed to confine grants to areas of education, health and science, community and social services, the arts, humanities, and religion. Protz expanded the vision to pry loose millions for cultural groups and historical restorations, including redevelopment of the historic Strand

and $8 million to the renovate Shearn Moody Plaza, a grandiose office building and railroad museum that Aunt Mary dedicated to her brother Shearn Senior. Despite the millions of dollars that went out for such projects, none of the Moodys ever demonstrated the grand vision of say, a Hugh Roy Cullen, who almost single-handedly built the University of Houston. Imagine the impact if the Moodys had built a first-rate university in Galveston or a world-class museum, either of which they could easily have afforded. Instead, they bequeathed a bunch of buildings with the name “Moody” over the front door. They gave a lot to Galveston, but they took a lot more than they gave.

A Family of Repo Men

Colonel W. L. Moody, the original, was born in Virginia and settled on the island after the Civil War, establishing a cotton business that specialized in cheating farmers. One way was to discount the farmers’ cotton bales for water weight on arrival, then let them sit on the wharves, soaking up the humidity; when an accommodating state inspector certified the bales for sale a few weeks later, the colonel reaped windfall profits. The colonel’s legacy to his heirs was not his fortune, which was fairly modest, but his disdain for fair play and his conviction that laws were to be used rather than followed.

If anything, W.L. Junior was more tightfisted and ruthless than his father. While his younger brother, Frank, a party boy, was off living it up in Cuba, W.L. Junior got the Moodys into banking, insurance, hotels, and newspapers—he used to boast that he had made Colonel Moody’s first million. When his position was secure, W.L. Junior blackmailed the colonel, threatening to resign and start a competing company unless the colonel banished Frank from the family business.

He Blames It All on Politics

By the turn of the century the Moodys had established a reputation as the repo men of the Gulf Coast, preferring to do business whenever possible through foreclosure. The island was Texas’ cultural and economic center in the late 1800’s, the second-wealthiest city in America, and the most important commercial center between New Orleans and San Francisco. Galveston’s main commercial street, the Strand, was known as the Wall Street of the Southwest. The generation of merchants that preceded Colonel Moody had built stately three-story mansions along Broadway, with turrets and spires and tall columns bedecked with the carved heads of European rulers. The hurricane of 1900 ended Galveston’s golden age, but the dominion of the house of Moody was just getting started. A few days after the great storm, the Moodys picked up their red-brick mansion on Broadway at a distress sale, ten cents on the dollar.

W.L. Junior’s son, Shearn, was said to be the meanest and toughest Moody of them all. Hotel baron Conrad Hilton, who had some dealings with the Moodys in the thirties, described him as the kind of man who liked the Depression. Shearn might have inherited the empire except that he died of pneumonia in 1936, when Shearn Junior and Bobby were babies. The way islanders tell the story, Shearn Senior’s pneumonia was caused by a business trip to colder climes—it seems he was too cheap to buy a heavy coat. After Shearn Senior died, his widow, Frances Russell Moody, used her fortune to become an international socialite. Shearn Junior and Bobby grew up in boarding schools and military academies.

As it turned out, W.L. Junior retained absolute power until his death at 89 in 1954. The bulk of his fortune went into the Moody Foundation, which he and his wife, Libbie Shearn Moody, had formed twelve years earlier. Libbie Shearn Moody set up her own trust to provide an income for her children and grandchildren. They received the trust’s interest, which in the sixties amounted to about $400,000 a year for each. The crown jewel of the Moodys’ fortune was the giant insurance company that W.L. Junior had founded in 1905, American National Life Insurance (ANICO), but the key to the treasure chest was the Moody Foundation. W.L. Junior and Libbie had willed the majority of the stock in ANICO to the foundation, which meant that whoever controlled the foundation also controlled ANICO, not to mention the banks, newspapers, hotels, ranches, and other property that the old man had accumulated.

After W.L. Junior’s death, power was transferred to the oldest and most favored of his four children, Mary Moody Northen, a naive, insecure woman who had devoted most of her life to looking after the old man. The rest of the family didn’t fare well. Though the estate was worth an estimated $440 million, only about $1 million went to the family. Mary got $250,000 and the mansion on Broadway; his second daughter, Libbie, got $200,000; and W.L. III was cut off with a token $1. W.L. III was continually defying the old man, but the last straw was when he quit the family business and became an oilman. W.L. Junior had hated oilmen since an unfortunate experience at the turn of the century, when he refused to invest in a new company that later became Texaco. Shearn Senior’s family had been given the shaft earlier. When Shearn Senior died, W.L. Junior cunningly bilked his widow and her two sons out of a large share of their inheritance by transferring some bad debts to Shearn Senior’s estate.

Why did the old man begrudge his heirs? The family version holds that he placed his fortune out of reach so that future generations of Moodys could appreciate the value of making it the hard way. The popular view, though, is that W.L. Junior just couldn’t stand the thought of sharing with anyone.

Will to Power

Until he decided to become a world-class business tycoon in the early sixties, Shearn enjoyed the easy, nihilistic life of Galveston’s most eccentric playboy. The sultry, sinister island seemed made for his bizarre taste and sense of style. “He hardly ever left the island,” recalls Jim Wohlenhaus, Shearn’s administrative aide from 1968 until 1975. “He said that he preferred to be a big fish in a little pond.” Wohlenhaus and his family lived at Shearn’s bayside compound, along with a houseboy, a gardener, a chauffeur, and a former Las Vegas dancer and choreographer named James Stoker, who is referred to as Shearn’s “personal companion” in court documents. A Newsweek article reported that Stoker and Shearn lived together as “husband and wife.” A small ruckus was created in the late seventies, when Stoker suddenly emerged as the director of two shows at the Mary Moody Northen Amphitheatre. (Shearn told Newsweek that Stoker is just a longtime employee and friend, and he denied being a homosexual.)

Many in Shearn’s entourage were homosexuals, sycophants, and lackeys. In the late fifties and early sixties, before Wohlenhaus had arrived on the scene, the ranch became infamous for its wild parties. It was a virtual fortress, with electronic gates and doors and bulletproof glass. Later, a new wing was constructed, with a slide connecting Shearn’s upstairs bedroom to the pool. Most of Shearn’s work was make-believe in those days, but he operated his “office” from his bedroom, said to resemble the bedroom that he now occupies in his mother’s Galveston mansion—a blaze of pink, with lots of stuffed animals. Poolside was a hangout for Shearn’s coterie—what one visitor described as “all these round-bottomed, curly-haired young men.” It was also home to four penguins.

Shearn became infatuated with penguins in the early sixties (“My penguin stage,” he calls it), when he slipped away from the island long enough to make several trips around the world. Shearn and his party were killing time in southern Chile while awaiting the start of Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro, when Shearn decided to go penguin hunting—he thought a few of the winsome creatures would look good around his pool and maybe help him feel cool. Shearn and his pals bagged nine penguins in the Strait of Magellan; when the birds began pecking him, Shearn peeled some rubber bands from the piles of money he always carried in a suitcase and muzzled the creatures. A U.S. Coast Guard crew made Shearn return the birds, but he wasn’t deterred. He bought some more penguins in Hollywood and had them shipped to his ranch. Unfortunately, these were mangy gray penguins rather than the handsome tuxed variety he had encountered in South America. Their toilet habits contributed to their quick departure.

The suitcase of money that Shearn carried in those days was a habit he had picked up from his grandfather. The old man had told him, “Use your money the way you would use an army, deploying only what is necessary and maintaining plenty in reserve.” Shearn called the stash his “grand army.” He had abandoned the suitcase by the time Wohlenhaus arrived in the late sixties, but one of the aide’s daily chores was to stop by the bank and pick up $2,000 in fresh cash. The bills had to be brand-new because Shearn liked handling crisp bills.

Stories of Shearn Moody’s eccentricities abound. For example, Shearn collected Hitler memorabilia and joked about turning the island into a fiefdom with himself as head of state. But such tales conceal rather than illuminate the man. “He is really a pitiable figure,” said one former associate, who, like almost everyone else I talked with, didn’t want to be identified.

Nearly everyone close to Shearn Moody recognizes the central contradiction of his character: He fancies himself a manipulator of men, but the evidence is overwhelming that Shearn himself is most often the manipulatee. A longtime acquaintance describes Shearn’s compulsion to control as his “will to power.” Life was an opera, Shearn liked to say, and he was its director. His collection of Hitler artifacts included a copy of Triumph of the Will, a classic Nazi propaganda film that demonstrates how manufactured events can be used to control a nation—or a legislative committee or a jury or merely a handful of would-be friends. It was the propaganda aspect of Nazi dogma that fascinated Shearn, not anti-Semitism. His politics were similarly focused more on style than content. He referred to himself as a General MacArthur conservative, but he was a libertarian too. In 1972 he supported George Wallace, a man who he later believed conspired to cause his downfall.

When he was traveling the world in the early sixties, Shearn indulged his whims by purchasing items his grandfather would never have dreamed of owning—huge quantities of exotic perfumes, rare tapestries, even polar-bear skins (“My polar bear stage”). The old man would have sat straight up in his grave upon learning that Shearn had bought the rights to Taj Mahal, a movie made in India; W. L. Moody, Jr., had nearly exiled W.L. III from the family for giving an organ to Galveston’s silent movie house, believing strongly that organs belonged in church and movies were a passing fad.

But Shearn was approaching the age of thirty and searching for his identity. A relative recalls that when Shearn returned from one of his world trips, he seemed dejected and depressed: “I asked him what was wrong. He told me that now that he had been everywhere and done everything, there was nothing left for him in life.” The relative suggested that Shearn start a business, preferably something off the island, away from the Moody dynasty, away from the hangers-on and sycophants.

The suggestion must have appealed to Shearn. In 1963 he chartered a life insurance company in Alabama. Insurance was the bedrock on which the Moody fortune was founded, and Shearn’s obsession was to build an empire to rival anything the old man had done. He called his company Empire Life Insurance, and by the mid-sixties it was one of the fastest-growing conglomerates in America. Shearn was hailed as the boy wonder of finance and told reporters of plans to buy a labor union in a foreign country and to sell life insurance to the Russians. Shearn had finally found himself.

A Rocky Foundation

Shearn wasn’t easy to love, but Aunt Mary managed. He was like the child she never had. Equally eccentric, both were night owls who would sit up until dawn talking about art or opera.

Aunt Mary lectured Shearn for his salty language and scolded him for his lifestyle, but she was always forgiving in the end. Already a widow of 62 when her father died, she had never cooked a meal or packed a suitcase—she had never even written a check until the mid-fifties, when she was thrust into the job of CEO for the Moody holdings. She didn’t trust airplanes, air conditioners, or anything else that wasn’t part of her father’s world, and she wasn’t altogether comfortable with banks. For years several hundred thousand dollars of uncashed ANICO dividend checks were stashed around the mansion, much to Shearn’s annoyance.

In the mid-fifties Aunt Mary appointed three nephews to serve with her on the Moody Foundation board —Shearn and Bobby Moody and their cousin, W. L. “Billy” Moody IV. It galled Shearn that all he could do with his grandfather’s millions was decide which church, university, or historical project would get the money. Shearn was more than galled; he was outraged, and he announced his intention to control what he considered his birthright—the foundation and its assets.

The foundation board soon found itself hopelessly deadlocked, 2–2, with Shearn and Bobby paired on almost every vote against aunt and cousin. In the late fifties Texas attorney general Will Wilson intervened, threatening to break the impasse by appointing five outsiders to the board. Their majority in jeopardy, the Moodys negotiated a compromise and agreed to accept three outsiders. But there was a clinker in this equation. Billy IV, a maverick who grew up on a ranch near Junction, far from the old man’s direct influence, sided with the three outsiders. This created an outsiders’ majority that thwarted Shearn’s ambitions.

Though Shearn and Bobby had a common interest—getting control of the Moody fortune—there wasn’t a great deal of brotherly love lost in their relationship. It was cordial, even friendly, but as Shearn told an interviewer for Finance magazine in 1966, Bobby “has a tendency of wanting to run everything, but, frankly, I think he’s wrong half the time.” No doubt Bobby felt the same way about Shearn. Two years older, Shearn believed that he was entitled to call the shots. “Shearn is probably the more intelligent of the two,” said a family friend, “but Bobby has a mind for business. Bobby would come up with a new idea, and sooner or later Shearn would copy it and claim it as his own.” Insiders say that it was Bobby who got the other Moodys to compromise when in 1968 Shearn was allowed to buy his grandfather’s private bank, W. L. Moody and Company, Bankers, Unincorporated, for $800,000. But they all wanted something for themselves from the foundation: a ranch for Billy IV, a resort in Virginia for Aunt Mary. Bobby had his eye on the grandest prize of all—the Moody National Bank. In 1978 Bobby was the high bidder for the foundation’s 51 percent block of Moody National Bank stock. For $4.6 million he got a true bargain—the bank controlled the Libbie Shearn Moody Trust and a large block of ANICO stock. Shearn had set his sights on the small bank and an insurance company, both of which were in financial ruin, while Bobby was making his move on the Moody empire.

Conning With Cohn

It is hard to pinpoint the exact date that Shearn Moody, Jr., made the transformation from eccentric to sleazeball, but it may have been the spring of 1969, when he hired Senator Joseph McCarthy’s old lawyer Roy Cohn. Shearn’s lobbyist, Jimmy Day (later twice convicted of fraud in cases unrelated to Shearn), was attempting to ram through the 1969 Legislature a bill that would have siphoned millions of dollars from the Moody Foundation and diverted them to Shearn, Bobby, and their cousins. When Aunt Mary sided with other board members in opposing the bill, its failure was assured. That’s where Roy Cohn came in. Having been thwarted by the Legislature, Shearn turned to the courts. Cohn’s job was to find a way to snatch the foundation from the outsiders.

Cohn was a brilliant attorney—nervy, vicious, and unencumbered by scruples. A generation of American television viewers had been repelled by the image of the mad McCarthy scowling and nodding as the greasy Cohn whispered advice in his ear. But what repelled most people fascinated and reassured Shearn, who referred to Cohn as the Doberman. Though they were cut from different cloth, Shearn Moody and Roy Cohn had much in common, starting with their distrust of established authority. They saw conspiracies in the legislative and judicial systems, which they regarded as corrupt, and shared a passion for right-wing crusades and shady dealings. Like Shearn, Cohn was reported to be homosexual, an accusation that Cohn denied right up until he died last year of AIDS. Finally, each understood the other’s lust for money. Cohn must have known about Shearn’s infamous loathing for attorneys (Shearn called them camels, and he went through them one after another), but for a hefty retainer and another $1,000 cash a day as his trial fee, Cohn could live with the abuse. Shearn deluded himself into believing that he controlled the attorney, but Cohn knew who was in charge: He was, and everyone except Shearn knew it. When there was a complicated brief to write, Cohn had Shearn pay for an around-the-world ticket on a Pan Am flight out of New York and secluded himself for days in the first-class section to work on Shearn’s problem.

On a yacht trip from New York to Galveston in the summer of 1969, Roy Cohn and Shearn Moody devised a strategy to gain control of the Moody fortune. At the time, ANICO was in the process of loaning millions of dollars to finance construction of the Las Vegas strip, some of it to people with Mafia connections. Cohn knew that the Moody Foundation–ANICO–Vegas connection was a natural headline grabber. When he denounced ANICO as a “bank for the mob” in testimony before a legislative committee, the story was gobbled up by newspapers and magazines nationwide. Using Shearn’s cousin David Myrick as the plaintiff, Cohn filed a $610 million lawsuit against several ANICO directors, charging them with serious improprieties and self-dealing. But a subsequent investigation ordered by Texas attorney general Crawford Martin disclosed that Myrick was only a “front man.” The AG’s report found that Shearn was behind the scheme, that he knew the charges were false, and that he made them in an attempt to inflame public opinion and compel the ANICO directors and the outside trustees of the foundation to resign.

The strategy failed. All Shearn got out of the Myrick suit was a huge legal bill. The failure didn’t dent his ambitions, however. In a second suit, in 1970, this one targeted at the directors of the Moody Foundation, victory was achieved, not only for Shearn but also inadvertently for Bobby. Victory came in the form of a judicial ruling that attorney general Wilson’s original board-packing deal in the fifties was illegal. Control of the foundation was returned to Mary Moody Northen, who, after much deliberation, reappointed Shearn and Bobby but not Billy IV. It isn’t clear why Aunt Mary turned her back on Billy—except maybe to avoid another stalemate—but it is clear that this was a turn of events ardently desired by both Shearn and Bobby. After that, things went smoothly until the eighties. Each of the three Moodys on the board had private projects and got along by going along. Shearn was finally getting his way.

The Alchemist

At times Shearn could be practical and even generous. He remembered with some embarrassment the old man’s appalling cheapness and told of a cross-country train trip with his grandfather when the old man flipped a paltry fifty-cent tip to a harried porter. Though only a teenager at the time, Shearn dug into his own allowance and gave the guy $20. Later Shearn’s generosity would take the form of allowing certain loyal associates to carry overdrafts at his private bank and to borrow large sums without collateral. “Shearn used the bank the same way the old man had, for pocket money,” recalls A. R. “Babe” Schwartz, who was one of Shearn’s attorneys and a W. L. Moody bank board member in the late sixties and early seventies. Schwartz himself had borrowed more than $200,000. When the bank failed in 1972, Shearn personally assumed the loans and overdrafts, charging them off against future fees and salaries. The only person who lost money in the bank closure was Shearn Moody.

But the same man who could bankroll his friends’ debts also had a knack for making powerful enemies. Among them was former governor John Connally —whose law firm, Vinson and Elkins, had represented the outside trustees whom Shearn was trying to remove from the Moody Foundation. Another was attorney general Crawford Martin—“John Connally’s stooge,” as Shearn once called him. Martin’s office had alerted Alabama officials that something fishy was going on at Shearn’s insurance company, Empire Life—a move Shearn believed had been choreographed by Connally.

Shearn had chartered his company back in 1963 with assets of only $256,000, small change in the insurance business. Yet by the end of 1968 Empire Life had expanded to sixteen states and reported assets of $60 million. What made this phenomenal growth possible was a device Shearn borrowed from Bobby, who had capitalized his insurance company by assigning it all of his interest in the Libbie Shearn Moody Trust. Shearn, however, assigned Empire Life only 40 percent of his share, amounting to only $150,000 a year. He convinced the Alabama insurance commissioner that his share’s true value, measured over his projected lifetime, was $14.4 million. For nearly eight years, that was the amount Empire Life carried on its books.

After Crawford Martin waved the red flag, a new commissioner reviewed the company’s assets, downgrading the value of Shearn’s 40 percent interest in the trust to $4.4 million. With $10 million wiped off the ledger in a single stroke, Empire Life collapsed and went into the hands of a receiver. That was in 1972. A short time later the receiver, along with the shareholders, sued, charging Shearn with fraud.

In the autumn of 1976 Shearn’s case was heard by a federal district court in Dallas. Lawyers wanted Shearn absent from the trial so he had himself hospitalized, a ruse that he used many times to avoid testifying. Cohn tried to convince the jury that the charge was just a misunderstanding brought about by former attorney general Crawford Martin and other vindictive politicians. He also argued that Shearn Moody was only the “titular head” of Empire Life, not responsible for its management. Shearn testified by deposition that he was no more than “the flag, the symbol” of the conglomerate and compared his role to that of the queen of England and the emperor of Japan.

Lying in his hospital bed miles from the witness stand, Shearn still managed to sabotage his own case. Lawyers for the plaintiffs introduced a rambling memo that Shearn called his Complex Financial Engineering Plan, which outlined a scheme to subvert the law and milk all the corporations he could get his hands on. A former Alabama insurance commissioner told how Shearn had bragged that he had “killed Crawford Martin” (who died of a heart attack a few days after a brutal deposition) and how he had threatened to get the insurance commissioner. The crusher, though, was the testimony of a former Empire Life vice president who recalled that when he had warned Shearn that his disregard for the policyholders was unacceptable, Shearn had replied, “F—the policyholders.”

Shearn had a chance to settle out of court for $875,000 before the jury began deliberation. Cohn phoned Shearn and begged him—begged him repeatedly—to pay up and cut his losses. Shearn stubbornly refused. That may have been the only time Shearn spurned Cohn’s advice, and it cost him dearly. The jury found for the plaintiff, establishing Shearn’s negligent mismanagement and breach of fiduciary duty, and set damages at $6 million plus interest. This debt, now estimated at $12 million, is still outstanding.

Quasi-Legal Egos

Shearn has an affinity for lowlife, a long-running pattern of attaching himself to crooks, informants, and con men who will do his bidding. Shearn’s so-called will to power is not supported by a corresponding will to act. Under all that bluster, a tiny voice seems to cry out, “Beat me, whip me, make me do bad things.” Once, when asked why he let so many people leech off him, he responded, “They amuse me.” After Roy Cohn departed to stalk larger game, Shearn went through a procession of attorneys. He hired them on impulse and fired them when he tired of paying their fees. One lawyer was hired on the advice of two fortune-tellers, not an uncommon practice for Shearn, who required that prospective employees have their horoscopes screened by James Stoker. Some of the attorneys Shearn fired eventually went away with a bundle—only after they sued him in court.

In the mid-seventies Shearn fell under the influence of another ambiguous figure, a former ANICO agent named Norman Revie. Cohn had originally hired Revie as a private investigator during the ANICO suits, but by 1975 Revie had become Shearn’s administrative aide and guru. When people speak of Shearn Moody these days, they also speak of Norman Revie, as though the two are inseparable. In a way they are; Revie is a codefendant in the criminal charges currently leveled against Shearn.

A smarmy, heavy set man of mystery, Revie is said to have an uncanny ability to organize documents and keep track of the maze of files that is all that remains of the empire. Though Revie isn’t a lawyer, he acts as if he is, and so does Shearn; the two of them are constantly drafting quasilegal documents. Some believe that it was Revie who persuaded Shearn to ignore Roy Cohn’s advice about settling the 1976 Empire Life fraud case. “If Shearn wasn’t constantly in legal trouble,” one lawyer says, “Norman Revie wouldn’t have a job.”

In recent years Revie has developed a Svengali-like hold over his boss. “Shearn won’t take a leak without asking Norm,” I was told. “It’s like an addiction. Shearn has to have his daily Revie fix.” When Revie is not around, Shearn is meek and almost helpless, but as soon as Revie walks into a room Shearn becomes the assertive tyrant that his grandfather must have been. Their relationship’s psychological gravity alarms some of Shearn’s close friends. A lawyer later implicated in the Moody Foundation scam relates an incident a few years ago at the Hotel Washington, a Moody-owned hotel in Washington, D.C., where Shearn frequently hides out. Revie was in Galveston at the time, and the lawyer and a psychologist spoke with Shearn about Revie’s apparent influence. Shearn agreed that he had a problem and asked the doctor to help him. But first, he said, he would have to check with Norman.

One Moody family friend points out that without Revie’s close supervision, Shearn could have even more problems. His almost naive amorality, his sense that he is above the law, often results in some pretty stupid stunts. When the Empire Life fraud judgment was being reviewed by the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, Shearn had the audacity to place personal calls to the judges. And when the case reached the Supreme Court, it is alleged, Shearn ordered sophisticated (and illegal) bugging equipment from Europe and tried to lease office space across the street from the Supreme Court building, apparently to keep surveillance on the justices.

So Right, So Wrong

The sorriest aspect of Shearn’s abuse of the Moody Foundation is all the good the foundation could have achieved but didn’t. Instead, throughout the seventies and early eighties, Shearn got the foundation to give millions of dollars to his pet charlatans, particularly those who carried the banner of the far right. His scheme to publish a book blasting the Texas insurance commissioner was so far-fetched it was almost comical. Shearn selected a former legislator and failed insurance executive named Jack Love as the author. Love would have been hard-pressed to write a coherent grocery list, much less a publishable book. Although Love went through $500,000 of his $750,000 grant without producing a single page, Shearn still landed him a second grant of $500,000. In 1981 Shearn arranged a $250,000 grant for Howard Phillips of Washington, the founder of the Conservative Caucus, to host a conference on Star Wars at the Hotel Galvez. The conference headliners included Senator Jesse Helms, Major General John Singlaub, and Washington journalist Jeffrey St. John, who spoke on “Restoring the Monroe Doctrine.” One of the hosts was a card-carrying zealot named Doug Caddy, the Texas connection to the Moody grant.

Shearn was instantly captivated by Caddy, a dapper and immaculate figure who looks like G. Gordon Liddy without the hard edge. A lawyer and writer of right-wing books, Caddy had once officed with E. Howard Hunt at the same Washington public relations firm and for a time represented the original seven Watergate conspirators. Caddy’s ideological contacts went way back. One year while an undergraduate at Georgetown University, he roomed with Tongsun Park, later infamous as the Korean influence peddler. Caddy was a disciple of William F. Buckley too—he helped found Young Americans for Freedom in Buckley’s living room. When Shearn learned that Caddy was a writer, he proposed that he help Jack Love with the insurance expose. Love died a short time later, and Caddy inherited the project, eventually collecting $600,000 to finish that book and two others.

But Shearn had even bigger plans for Caddy. “Shearn told me that he was interested in the area of public affairs and asked me to set up a tax-exempt nonprofit organization and apply for grants,” Caddy says. “He told me that the Moody Foundation had eighteen million dollars a year to give away.” Between 1982 and 1984 Caddy received nearly $3 million from the foundation.

Shearn’s right-wingers made Bobby Moody and the staff of the Moody Foundation more than a little nervous. But that didn’t prevent them from letting Shearn pick the lawyer who would handle his friends’ grants. Until the early eighties, all grant applications had been investigated by either the staff or a Dallas law firm chosen by Bobby. Then Shearn accused the Dallas firm of discriminating against his right-wing grant seekers, and he persuaded the foundation to hire Thomas Troyer of Washington, a highly respected expert on tax-exempt charities, to handle all of his projects. What nobody at the foundation realized at the time was that Troyer was reviewing applications only for compliance with tax-code regulations. Troyer says he didn’t think it was his job to investigate the legitimacy of the applicants. He says he assumed that the staff was doing the investigating, just as the staff assumed that he was. In fact, the only person vouching for these groups was Shearn himself.

Caddy’s last project for Shearn would turn out to be a fiasco. In the spring of 1984 Shearn became convinced that the Alabama insurance commissioner was behind a conspiracy to kill him. He believed that organized crime had taken over Empire Life’s assets following his downfall and intended to cash in on a $12 million insurance policy on his life. The policy, he once said, was “tantamount to a murder contract.” Shearn hired Caddy to go undercover, attempting to compromise the Alabama insurance commissioner by getting him to accept a bribe. Just as Caddy was about to make his move on the commissioner and shortly before a critical hearing in bankruptcy court, Shearn vanished. Trying to explain to the judge why Shearn wasn’t in court, his attorney let it slip that one of Shearn’s agents was running a sting operation designed to expose the Alabama insurance commissioner—whose representatives just happened to be sitting in the courtroom. That slip may have ended Caddy’s role in Shearn’s schemes, but it set the stage for the entrance of a con man named William Pabst—the central character in Shearn’s fated denouement.

Smooth Operator

The conspiracy to swindle the Moody Foundation began in October 1984, or so it is alleged in the federal indictments. There is no evidence that Caddy kicked any of the grant money back to Shearn, which may be the reason Shearn found William Pabst more to his liking. Pabst agreed that Shearn had been cheated by the system and that it was up to them to do something about it. Pabst’s first project was to conduct a smear campaign against the judge in Shearn’s bankruptcy case. He published a bound volume on the judge’s alleged improprieties and distributed it at a judicial conference in Florida, and he sent letters making similar allegations to the Department of Justice in Washington.

Pabst was more of a crackpot than an ideologue. He pretended to be an attorney. He had once been accused of operating a law school diploma mill. And he was under indictment in Houston for swindling money from a charitable foundation operated by Atlantic Richfield. But his true talent was in recognizing the fine line between a man’s greed and his propensity for larceny.

Pabst already had a network in place when he met Shearn, and within a matter of days he had expanded it to accommodate a gift horse as enormous as the Moody Foundation. The front for his scam was an organization he set up under the catchy name of the Centre for Independence of Judges and Lawyers in the United States. Supporting CIJL were dozens of other suspicious foundations and a small cadre of lawyers and bagmen. Pabst’s scheme was to find otherwise legitimate grant seekers who would be willing to kick back most of the money and let Pabst run things. An expert on tax-exempt foundations, Pabst found most of his recruits at conferences, where he lectured on strategies for tax-exempt foundations. The recruits were led by the hand through every step of the grant process. Pabst or one of his people composed the grant application and delivered it to the Moody Foundation. They also picked up the Moody checks and redistributed the funds through the network, allowing the grant seeker to keep about 20 percent of the take. The Moody Foundation received no applications for grants from William Pabst or from CIJL itself, but there are allegations, supported by considerable evidence, that within weeks of Pabst’s first meeting with Shearn, hundreds of thousands of dollars from the foundation were flowing through the CIJL network to Pabst. So smooth was Pabst’s operation that even after he was convicted of the Atlantic Richfield swindle in May 1985 (and sentenced to ten years in prison), funds from the Moody Foundation continued to pour in. By the time federal and state investigators got wind of Shearn’s misadventures in the summer of 1986, Pabst had skipped the country.

The Game’s Over

It seems incredible now that nobody saw trouble coming. Shearn, especially, had plenty of warnings. In October 1985, nearly a year before an official investigation started, the spurned Doug Caddy blew the whistle on Pabst’s scam. After advising Shearn that his association with Pabst could be disastrous, Caddy went to Moody Foundation attorney Irwin M. “Buddy” Herz with information that more than $500,000 in foundation funds had already ended up in the coffers of Pabst’s CIJL. Caddy also charged that Pabst and Shearn were attempting to shake money out of legitimate grant applicants by threatening to scuttle their applications unless they diverted most of the money to CIJL. One such target, a well-known right-wing professor from the University of Dallas named Mel Bradford, had urged Caddy to alert the foundation board. Caddy’s motive may have been revenge, but many of his allegations were later repeated in the indictments.

Buddy Herz, and before him his father, had a long association with the Moodys and an abiding loyalty to the foundation. Herz and Bobby Moody both knew that Shearn was tight with Pabst, but by this time they were so numbed by Shearn’s associating with dubious characters that it never occurred to them that he would play fast and loose with the family’s most sacred trust. In their opinion Caddy’s accusations were nothing more than an extortion attempt. “Continue to give me grants,” they thought Caddy was saying, “and I’ll keep quiet.”

Even as Caddy was sounding the alarm, Shearn was busy starting new fires—in particular two new $250,000 grant applications for groups founded by Robert E. Bauman, the reactionary onetime congressman from Maryland who lost his House seat after being accused of soliciting sex from a teenage boy. A few days after Caddy made his accusations, the foundation board denied the applications from Caddy and Mel Bradford but approved Bauman’s grants.

Herz wrote to Tom Troyer, the foundation’s Washington lawyer who handled Shearn’s grant projects, asking for an investigation. He detailed Caddy’s charges and noted that Shearn had assured him that they were nothing more than a “shake down” attempt by Caddy. Troyer wrote back that it wasn’t his job to investigate grant applications and suggested that the foundation hire an outside law firm for the purpose. At this point Shearn intervened. He recommended his own point man to spearhead the investigation of charges against him—none other than Robert Bauman, who was soon to be heavily implicated in the scam himself. Troyer gave Bauman his seal of approval, assuring the foundation that the former congressman had only a “very limited prior relationship” with Shearn and could be completely impartial. What Troyer failed to mention was that both Shearn Moody and Norman Revie were listed as directors of the two Bauman foundations that had just received Moody grants, an inexplicable oversight, considering that Troyer himself had chartered the foundations.

More than four months after Caddy first sounded the alarm, Bauman and Troyer went quietly about the business of selecting a law firm to conduct the probe. The Manatt Report, as the law firm’s findings were called, was completed four months later, in late July 1986. It supported Caddy’s contention that Moody Foundation grant money had been kicked back to William Pabst. But, not surprisingly, it mentioned Bauman only in passing and gave Shearn a clean bill. “Caddy was incorrect,” the report said, “in inferring that Shearn Moody had any knowledge that Pabst had engaged in these activities.”

Even before the Manatt Report reached his office, assistant attorney general John Vasquez had decided to conduct his own investigation—he had been alerted to the situation by Moody Foundation lawyers who, fearing that a threatened lawsuit by Caddy would make the accusations public, decided to alert the AG’s office to their own investigation. Reading the Manatt Report only reinforced Vasquez’s determination. “The Manatt Report was unsatisfactory,” said Vasquez, a soft-spoken man with a gift for understatement. Since Vasquez had no investigators under his command, he suggested that the Moody Foundation hire Clyde Wilson, the noted Houston private detective who had broken the Hermann estate scandal. Wilson agreed to take the case, provided that he was permitted to submit any findings of criminal activity to the proper prosecutorial authorities, a condition the Moody Foundation accepted.

Wilson was puzzled that Shearn went along with his demands. After all, some of the Hermann Hospital trustees had been forced to resign as a result of his investigation. “I began to understand the next morning, when Shearn visited my office and started talking about getting me a four-hundred-thousand-dollar grant,” Wilson said later. Shearn had once again badly misjudged the situation and the man. Clyde Wilson is as ornery as they come, a large, lean, mean maverick with a battered face and a glass eye that he enjoys popping out and handing to first-time visitors. Clyde’s credo is printed on a sign that sits behind his desk: “Old age and treachery will overcome youth and skill.” If Shearn hadn’t realized that the game was over when Caddy blew the whistle, he certainly should have realized it when Clyde Wilson ushered him out the door.

During the autumn of 1986 Clyde Wilson submitted regular reports of his findings to the foundation, the attorney general of Texas, the U.S. attorney in Houston, and the district attorneys of Galveston and Harris counties. There was evidence that at least four Moody grant recipients had kicked back money to Pabst, as much as 80 percent in some cases. Between $2 million and $3 million of it had apparently been channeled through a network of phony grants.

Though at first glance the recipients appeared reputable, their projects often bordered on the ludicrous. Dr. Robert D. Earl, a Houston dentist, received $600,000 to study, among other things, the dental malformations of convicts to determine whether people who “look different” from the general population are more likely to end up in prison—he must have come to some interesting conclusions by now. The process went like this: A woman from Pabst’s office would have Earl sign a request for payment, hand-carry the request to the Moody Foundation, pick up the check, bring it to Earl, then instruct the good dentist to issue Earl Foundation checks to various people and groups he had never heard of. Earl never appeared to understand what was happening, except that he was getting richer. An assistant attorney general told me that Earl still writes occasionally, telling the attorney general’s staff all the good things he has been able to buy with his grant money and asking how he can go about getting more charitable donations. Earl was among those indicted.

Wharton County Republican chairman Merle Carlson received a $375,000 Moody grant to “underwrite a program to develop human rights awareness” and publish a booklet for prospective jurors. He subsequently wrote checks to CIJL totaling $292,214. He was also indicted, but the indictment was later dismissed.

The most pathetic thing about Shearn’s alleged involvement with the scam is that hardly any of the money ended up in his own pocket. On the other hand, records subpoenaed from CIJL reveal that considerable amounts went to attorneys who were representing Shearn, some of whom appear to have been part of the scam.

Large amounts also went to pay debts piled up from Shearn’s extravagant lifestyle, particularly his huge hotel bills. W. L. Moody, Jr., whose idea of breakfast was splitting an egg with his wife, would have been appalled at the way his bucks were frittered away. You can almost hear the old man’s chains rattling.

Laying the Blame

Shearn’s problems will not end with his two federal trials. He is a party in numerous other legal actions, including a civil racketeering suit filed by the bankruptcy trustees. The racketeering suit alleges that Shearn and Norman Revie stashed away at least $1 million in assets that should have gone to Shearn’s creditors. The lawsuit names Bobby Moody as a coconspirator, which some regard as a ploy to get Bobby to pay off Shearn’s debts. In the civil case, lawyers alleged in court that Robert Bauman was Shearn’s bagman. To date, Bauman has not been indicted in the criminal cases. It is speculated that he will be a key witness at the criminal trials.

Life goes on as usual in Galveston. The twenty-story ANICO building, the city’s only skyscraper, sits like an alabaster idol over the wharfs and the renovated Victorian face of the Strand. Bobby now has complete control of the Moody empire. Shearn has been replaced on the foundation board by Bobby’s son, Ross. Aunt Mary’s seat is now occupied by Shearn and Bobby’s mother, Frances Russell Moody Newman, a resident of Galveston, Monte Carlo, and Palm Beach.

Even though W. L. Moody and Company, Bankers, shut down fifteen years ago, its doors are still open during business hours, just as they have been since the bank was founded in 1866. It is a ghost bank now, its cashiers’ cages smelling of moldy records and sea rot, its marble lobby empty except for a faded sign advertising 1972 automobiles. A guard and a clerk paid by the trustees keep it open for the dozen or so safety-deposit-box owners who have never bothered to change banks. “Habits die slow on the island,” the clerk told me.

Shearn has been lying low since his indictment. He claims to be destitute (“living at the suffering of my mother”) and jokes about applying for food stamps. He compares his ordeal to that of Gandhi or the victims of the Inquisition. He’s still blaming all his misfortunes on John Connally, Crawford Martin, George Wallace, the CIA, Watergate, and the Mafia. Occasionally, islanders see him pattering around town, a potty, rumpled figure in house slippers and blazer. He was spotted not long ago digging through obscure tax records at the Galveston County courthouse, no doubt looking for a scrap of paper that would help win back his empire. After all this time you would think Shearn would be weary of the struggle, but that doesn’t appear to be the case. It must have something to do with breeding.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Galveston