This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Like an eccentric genius wary of prying eyes, Rice University is sheltered behind miles of manicured hedges and thick groves of live oak in the heart of Houston. It is a small school with big ideas and a lifelong identity crisis. Now in its seventy-seventh year, Rice is still obsessed with what it should be when it grows up.

For as long as I’ve known Rice students, faculty, and alumni, they have spent a lot of time thinking and talking about their school and where it’s going. That doesn’t happen at many campuses. One of my old Rice friends told me recently, “In my wife’s four years at the University of Texas, she didn’t give ten seconds of thought to UT as an institution. It was just there.” Rice is wrestling with a common problem in Texas intellectual life: It desperately wants recognition from the people who count, especially those on the East and West coasts. When the recognition has not come, the typical Texas reaction, at UT, for example, has been a smug complacency. But Rice puts itself on the couch.

Why hasn’t Rice made it? The school has some impressive credentials. For all the high-toned talk of academic community and the pursuit of truth, a university’s standing has mainly to do with its bank balance, the quality of its students, and the reputation of its faculty. Rice stacks up very well on two of those counts. Among private colleges it has the ninth-largest endowment ($930 million) and ranks fourth behind Harvard, Princeton, and Cal Tech in endowment per student. Every freshman class is near the top nationally in the percentage of National Merit Scholars.

The main reason Rice isn’t famous is its faculty. It’s good, but compared with those of the leading universities, the Rice faculty is small and its stars are few and far between. Only four academic departments have cracked the national top-twenty rankings of graduate programs. The school doesn’t even make much of a splash in its home city and state. Other private Southern colleges such as Tulane, Duke, and Vanderbilt are much more of a presence in their regions than Rice is here. In spite of recent recognition in college guidebooks and the national press, Rice can still fairly be described as America’s best unknown university.

It is a few minutes before noon on the Rice campus on a muggy day in late February. Eleven o’clock classes have just emptied, and students crisscross the quadrangle on their way to eat lunch. Most are dressed in baggy sweatshirts and jeans or T-shirts and shorts. “Wearing good clothes violates a social norm at Rice,” one student told me. A couple of years ago the undergraduates seemed almost gleeful when a Roper poll named Rice the worst-dressed campus in the country.

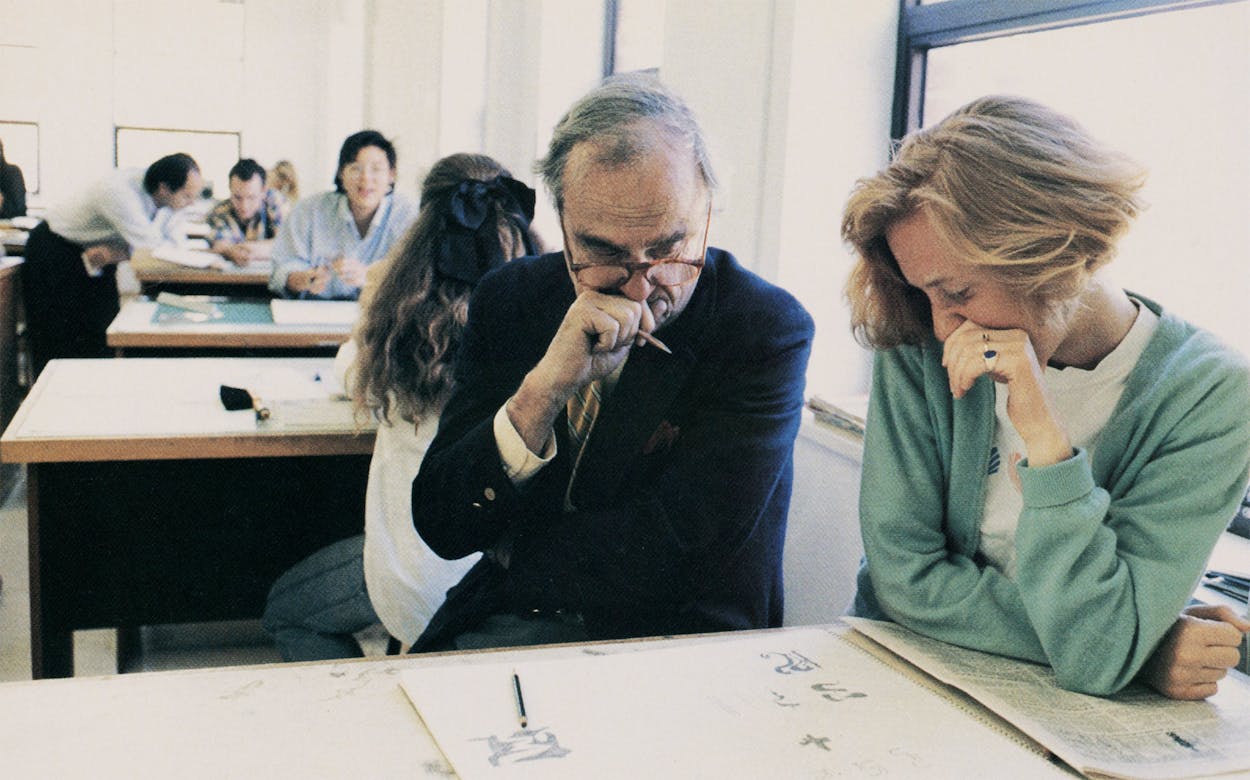

I head for Sammy’s, the cheerless cafeteria in the student center, where I share a table with two sophomores majoring in biosciences. Ronald Sass, a biology and chemistry professor I knew during my undergraduate days, comes over to join us. Soon the conversation turns to Sass’s sabbatical last year in Alaska, where he studied the greenhouse effect. The students forget their lunches and pounce on him with technical questions that quickly leave me far behind, but Sass’s answers are clear. The warming trend, already irreversible, will become obvious in thirty years or so. Rainfall will decrease, and the deserts will expand. What will be the result? “Social and political upheaval, with masses of people streaming across borders to the north,” Sass says. Like Mexicans fleeing to the U.S.? “And Americans pouring into Canada.”

Such encounters between undergraduates and professors are one of the things that set Rice apart from many other schools. “Every student has at least one professor to sit down and talk with,” an undergraduate told me —and not just teachers in the student’s own field. I was a history major, but I knew Sass because he often dined in the residential college (a cross between a dormitory and a fraternity) where I lived on campus.

Unfortunately, it is a sign of the times at Rice that faculty involvement with students is eroding. As part of Rice’s drive to make the big leagues, the administration expects more scholarly work from the faculty. So professors are more jealous of their time, and persuading them to spend much of it in the residential colleges has become more difficult. Sad but true, to realize its ambitions, Rice may end up sacrificing some of its strengths.

From the beginning, Rice’s identity and ambitions have been caught between the competing visions of its founder and its first president. William Marsh Rice, the son of a Massachusetts ironworker, had to quit school and go to work in a grocery store when he was 15. In 1838, at the age of 21, he migrated to Houston and went on to make a fortune as a cotton trader and investor. Childless despite two marriages, Rice decided he wanted to do something to help other poor kids get a start in life. In 1891, while living out his old age in New York, he endowed a college to be built in Houston after his death, and he arranged to leave it most of his money. Rice appointed as trustees prominent Houstonians and named as chairman his Houston attorney, James Baker, the grandfather of the present Secretary of State.

Rice died in 1900—chloroformed by a scheming valet and a crooked lawyer who had hopes of inheriting the estate under a forged will. Years of litigation passed before the real will was approved and the trustees could begin their work. Soon it became obvious that they had something grander in mind than providing free education for children of the poor. Their choice for the school’s first president was Edgar Odell Lovett, a mathematician and astronomer recommended by Woodrow Wilson, then president of Princeton, from his own faculty. Lovett, who had to be persuaded to move to Texas, wanted no part of an invisible local trade school or a backwater Southern college. The trustees were easily convinced.

The Rice Institute opened in the fall of 1912 on a 290-acre campus stitched together from swampy farms along a mosquito-infested bayou west of Houston. Its main building, an elegant brick-and-marble structure rising abruptly out of the prairie, must have looked like a boundary marker at the end of the civilized world. But Rice had a $10 million endowment and an Ivy League president whose announced aim was to build a university of the first rank and train a new intellectual elite on the raw Gulf Coast.

Lovett was to be disappointed. After World War I, inflation ate away at the value of the splendid endowment, and the Depression of the thirties almost finished it off. Many of the most distinguished members of Rice’s initial faculty left, including English biologist Julian Huxley, who had gained local notoriety by championing the theory of evolution. Like many a family whose savings shriveled in those hard days, the school suffered its genteel poverty quietly, too proud to appeal to the community for help—if any was to be had. By then Rice had gained a reputation in Houston as an elitist school that looked outside Texas for its values.

Rice might have remained just another struggling little Southern college if it hadn’t been for the intervention of two alumni—Harris County judge Roy Hofheinz and George R. Brown of Brown and Root. In 1942 they persuaded the trustees to buy into the Rincon oil field in South Texas. Oil money eventually made Rice rich again, and Brown became the university’s best fundraiser, most generous donor, and dominant trustee—leading to the waggish suggestion to change the school’s name to Brown Rice U.

By the time I arrived in 1960, although Rice now called itself a university, it was still more the school its founder had envisioned than the one Lovett had hoped for. Most of the students weren’t poor kids, but many of us came because of the free tuition and would probably have gone to a state university if Rice had cost as much as other private colleges. Most of the 1,500 undergraduates lived on campus in the residential colleges, which had been organized a few years earlier to provide focal points for student activities and, some hoped, to extend intellectual life beyond the classroom. There were about 500 graduate students, mainly in the sciences, but the emphasis was definitely on the undergraduates. Professors were expected to teach first and do research second.

In many ways I was the kind of student that William Marsh Rice had in mind when he donated his fortune to an unborn college. I came from a small town and a family that could be called struggling middle class. College opened a window on the great world beyond my flat West Texas horizons. I had grown up with the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, but some of my more sophisticated classmates read the New York Times and professors referred to the London Times, Le Monde, and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. The air was thick with names I had never heard and ideas I had never imagined. It was intimidating and exhilarating.

Sometime during my sophomore year my education started making sense to me. It wasn’t just committing mountains of facts to memory, though that played a part. It had more to do with developing critical habits of mind. At Rice little was sacred and almost everything was up for debate. Anyone guilty of sloppy thinking, in the classroom or just talking with friends, faced harsh judgment.

Rice in those days subscribed to the Social Darwinist doctrine of survival of the fittest. According to the official history of the university, 20 percent of the first freshman class flunked. That tradition was still alive in 1960. We humanities majors worked hard enough, but we had it easy compared with the science and engineering students. Engineers made up less than a third of the student body, but they played a much bigger role in campus mythology. They were the marines to our infantry, the commandos who hit the beaches first and took the most casualties. Engineers labored through six courses a semester, instead of the usual five, which meant they spent around thirty hours a week in classes and labs and then had to find time and energy to study and prepare written assignments. (“After Rice,” one of them told me a few years ago, “a job with IBM was easy.”) Their reward was rigorous grading according to a bell curve that condemned most to mediocre to poor scores. One successful Silicon Valley executive, who graduated near the bottom of his electrical engineering class in the early sixties, recently described his undergraduate education as an “intellectual and emotional boot camp.”

In the sixties Rice had a reputation as a good, tough school. It was good enough for us to use our degrees as springboards to top graduate and professional schools and good jobs, so we had reason to be grateful for our free education. But some of us had our doubts. Although there were outstanding teachers, the faculty was uneven in quality and the curriculum was narrow. Social sciences, art, music, and the study of non-Western cultures were almost nonexistent. Too often the university imposed a mindless rigor that tested students’ stability as much as their ability. Looking back, I think Rice was tougher than it was good.

Rice is a different place today. It has clusters of new buildings, more than half again as many students, twice the faculty, much broader course offerings, and a far richer campus cultural life. Professors no longer hand out bad grades in fistfuls, and students seem happier and more relaxed, although there is some grumbling about the rising cost of their education. Rice began to charge $1,200 tuition in 1965. The cost has risen to $5,300 this year, with an $800 increase—the biggest ever—scheduled for 1989–90. Even so, that’s a bargain compared with leading private universities like Harvard and Stanford, where tuition has climbed above $13,000. Rice also has an excellent scholarship program and prides itself on making sure that every student admitted will be provided the money necessary to earn a degree. On the average, undergraduates pay less than 40 percent of their tuition.

But much is familiar too. Rice still caters to undergraduates. Graduate students are more numerous now than they were in the sixties, but they live off campus and remain nearly invisible on it. Today’s undergraduates are bright, polite, unassuming, anti-elitist, and—how else to say it?—proud of each other. That makes for a remarkably autonomous and cooperative student culture. “Most students, even in science and engineering, will tell you that they learn more from each other than they do in class,” one said to me. The student-run honor system, a long tradition, works so well that cheating is almost unheard of.

The wry, self-deprecating sense of humor I remember has also survived. “Rice is like a summer camp with classes and tests—lots of them,” a sophomore told me. Said another, “Everyone I know here is either forty or twelve, except for a couple of nineteen-year-olds.” That sounded familiar. Part of going to Rice has always been dealing with the school’s “weenie” image, as we used to say (current campus usage is “weener”). In my day male undergraduates outnumbered the females four to one, so most had to find dates off campus or at other schools. One of my friends courted and eventually married a Pi Phi from the University of Texas. Years later I asked her what her sorority sisters had thought of Rice men. She didn’t even hesitate: “Squirrels.”

The best collective example of Rice students’ irreverent humor is the Marching Owl Band, or MOB. At football games the band laces its halftime shows with sarcastic jabs at everything from mass culture to opposing schools. The most notorious incident took place in the early seventies, when a MOB routine poking fun at Texas A&M and its canine mascot, Reveille, enraged the visiting corps of cadets. At the end of the game angry Aggies surrounded the Rice Stadium field house, where the frightened band members had taken refuge. Finally, food delivery trucks were backed up to the field house doors to extricate them, thus saving one MOB from another. The next year, a small East Texas high school returned the application materials Rice had sent, saying that because of the Aggie skit, it didn’t plan to send any more students to Rice.

Most familiar of all is the ongoing debate about Rice’s future. At the center of the controversy is the university’s fifth president, George Rupp, a former dean of the Harvard Divinity School with big plans for Rice. When he took over in 1985, Rupp described Rice as one of the very few private institutions “on the threshold of a major advance into the first rank of American universities.” Since then Rupp has come up with an enhancement program whose main feature is upgrading the faculty in numbers and quality. To achieve that, he says, Rice must raise more money and give more emphasis to research and graduate programs without sacrificing the quality of undergraduate education. Still, the question arises whether Rice will then stop being the sort of school it has always been.

Lean and craggy-faced, the 47-year-old Rupp sometimes sounds more like a management consultant than a specialist in comparative religion. He says that Rice has not “leveraged its resources,” as the leading universities have, by tuition increases, income from outside grants and contracts, and donations. “We’ve tended to sit back like an old dowager and just clip our coupons,” he told me. Rupp sees the competition for outstanding professors as becoming more and more expensive, because of the scramble for the top young Ph.D.’s and the escalating costs of scientific research. “The competition is excruciating,” Rupp said. “We are very rich, but compared with the people we’re competing with now, we are not very rich. We’re competing against Stanford and Harvard and MIT, and those people have very big war chests.”

The competition is not just for faculty but for students. Rice gets good students because it is cheaper than Stanford and Harvard and because Rice undergraduates have more contact with professors. Rice’s strengths have begun to be noticed. Last fall U.S. News and World Report ranked Rice ninth among national universities, citing its low student-faculty ratio, its standing in the sciences, and “an Ivy-level curriculum in the arts and humanities.” A year ago syndicated columnist George F. Will ran a laudatory piece on the school that called Harvard the Rice of the Northeast. But if Rice changes, will the best students still want to come?

Part of Rice’s appeal has always been its intimacy. Most students know everyone in their residential college and a good portion of all undergraduates. But size stands in the way of Rice’s ambitions. The top universities are bigger schools with extensive research facilities and huge libraries. The smallest school consistently at or near the top, Princeton, has half again as many students and faculty as Rice.

Rice’s smallness also means that less money is available to the school. Although annual giving by alumni is at record levels, the total number of living Rice alumni, 28,000, isn’t much more than half of UT-Austin’s current enrollment. Rice is far more dependent on its endowment than the top universities: according to Rupp, Harvard covers less than 20 percent of its annual expenses with income from endowment; the comparable figure for Rice is 60 percent.

To compensate for its lack of size, some say, Rice must make “creative use of smallness.” Rice can’t afford large graduate programs in every department. What it can do, Rupp says, is concentrate on multidisciplinary research—which bigger universities seldom pursue. Rupp’s plan calls for five multidisciplinary research centers at which professors can work and teach graduate students. One, the Rice Quantum Institute, already existed when he arrived, though it was little more than a name and an idea. Today it sponsors joint research in fields ranging from chemistry and space physics to computer engineering. The other centers are in biosciences, computer technology, social sciences, and humanities.

Perhaps Rupp is right that the centers are the best way for Rice to attract outstanding faculty. But a few longtime liberal arts professors are dubious about them. “In the sciences they’re for research,” one told me. “In the humanities they’re for conversation.”

Rupp would also like to make undergraduate education interdisciplinary. He has revised the curriculum with an ambitious purpose: bridging the gulf between the “two cultures”—science and humanities—that English writer C. P. Snow called to the Western world’s attention three decades ago. If Rupp has his way, all undergraduates majoring in sciences will be required to have a minor in humanities; humanities majors must minor in sciences. At least for the next few years, however, the minors will be optional—thank goodness. For most students in the humanities, the prospect of taking upper-division courses in the sciences is truly daunting. (Back in the fifties, all Rice freshmen had to take science-engineering math, which contributed heavily to the attrition rate.) Any students who volunteer for the new minors are likely to be scientists or engineers. Unfortunately, that won’t solve the problem Snow had in mind, which was the ignorance of humanists and policymakers about science, not the reverse.

As the first guinea pigs in this experiment, this year’s freshmen were required to enroll in new interdisciplinary survey courses taught by teams of faculty. Student reaction was critical, especially of the science course. “If you’d already had the stuff in high school honors courses, it was boring,” a freshman told me. “If you hadn’t, it went too fast and was too hard.” In the English and history departments, so much faculty manpower was diverted to the new courses that fewer upper-division courses were offered than usual.

“Rice wants it all,” a prominent history professor said. “Great teaching, intellectual intimacy between faculty and students, service to the university, and good scholarship. That puts a tremendous burden on the faculty. That’s what’s bad about it, and that’s what’s good about it.”

In spite of what George Rupp says, publishing and teaching are often antagonistic. The danger in his determination to bring in ambitious, research-oriented professors is that the faculty will put teaching on the back burner. Rice so far has avoided the practice, common in many universities, of letting graduate students handle much of the undergraduate teaching load. But the temptation may become irresistible in a university where publishing comes first. Already, written scholarship is the primary factor in new appointments.

“In the past many Rice professors were known for their tremendous dedication to teaching and their service to the university community,” Dennis Huston, an English professor who has won more than his share of teaching prizes, told me. “Today those types either aren’t hired or are washed out.” In 1987 Rice students, who are known for anything but activism, signed petitions and demonstrated against the denial of tenure to Joseph Martin, a biology professor who had won several teaching awards. Martin had the highest rating in his department in student course evaluations, but his senior colleagues judged his research unworthy. He now works for a pharmaceutical company.

Part of the problem with Rupp’s emphasis on scholarship is illustrated by the case of Roger Ulrich, an assistant professor of art and art history who came to Rice five years ago after receiving his Ph.D. from Yale. Next fall Ulrich will move to Dartmouth. He isn’t leaving because he expects to find better students there; like everyone else I talked to, he thinks Rice undergraduates are as bright and well-prepared as any in the country. He is a native of New England, so that played a role in his decision, and he is also getting a raise. But one big reason is the conflict between teaching and research.

At Rice Ulrich has put a lot of time into teaching. Although he specializes in classical Greece, he has taught courses on ancient art and archeology from Egypt to Rome. Students wanted the courses, and there was no one else among Rice’s small corps of art historians and classicists who was capable of offering them. At Dartmouth four other professors will help cover those fields and Ulrich will have a lighter teaching load. That means more time for research and writing.

Ulrich has managed to finish writing a book, but it hasn’t been easy. The Rice library, which barely makes the list of North America’s top one hundred research libraries and ranks behind those at Oklahoma State and the University of Manitoba, proved entirely inadequate. He found himself using the cumbersome interlibrary loan system and making trips to UT. On the day I interviewed him, he had just returned from the Rice library, where not one of the five books he wanted was in the collection. “It happens all the time,” he said, shrugging. “The library here has only been trying to build up its humanities holdings for the last forty years or so, but Dartmouth’s collection dates back two hundred years, and in New England I’ll be within easy reach of many others that are even better.”

Talking to Ulrich, I thought of my recent visit to the Rice library. Its current renovation is stalled for lack of funds. There is a grand new foyer, but one of the two main reading rooms is closed and locked, piled high with unused furniture and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century newspapers and journals. In some parts of the open stacks, the shelves are so close together that you have to walk sideways.

I heard an entirely different story on the other side of campus from Richard Smalley, a chemist who is the chairman of the Rice Quantum Institute and one of the university’s emerging stars. His laboratory’s discovery of buckminsterfullerene, a carbon molecule that looks like a soccer ball, was the cover story in the January 1989 issue of Science News. The molecule is all but impervious to the most intense heat and light and may prove to be the oldest and stablest molecule in the universe.

A wiry Midwesterner in his middle forties who dresses in jeans and wears a neatly trimmed beard, Smalley came to Rice in 1976, three years after getting a Ph.D. from Princeton. He thought it was an out-of-the-way place he would be leaving before long. He has had plenty of opportunities: In 1980 Wisconsin offered him a job, five years later it was Columbia, and then Princeton made two serious attempts. He declined them all.

“In the end it turned on what would be the most productive place to be,” Smalley told me. “The only thing that matters from my standpoint is how nurturing the place is for research.”

For Smalley, Rice is very nurturing. He holds an endowed chair with an annual salary of more than $100,000 while the average full professor in science and engineering earns around $70,000. His lab and research team is one of the best-funded groups of its size in the country, with an annual budget of around $500,000. But Smalley teaches few undergraduates. This year just two, along with eight graduate students, enrolled in his only undergraduate course.

Obviously, any university worthy of the name would be proud to have a Rick Smalley in its ranks, and his decision to stay at Rice—on practical, not sentimental, grounds —speaks well for the school’s ability to compete with the best for outstanding faculty. But it is hard to escape the conclusion that in the future Rice will have more Rick Smalleys, fewer Dennis Hustons and Joseph Martins, and lots of young professors like Roger Ulrich caught in the middle.

In the end, a lot of Rupp’s ambitions for Rice will depend on money. As one administrator said to me, “The generation of ideas is outrunning the availability of funds.” Rupp had to scale back plans for a new music building when money ran short. The new computer center recently received a whopping $23 million grant from the National Science Foundation, but it has yet to find a home on campus. Any major improvement of the library is years in the future.

In such a climate, the most vulnerable part of the budget is intercollegiate athletics—especially football, a sport at which Rice hasn’t been competitive for years. It may seem incongruous for a college as small and as academically oriented as Rice ever to have played football, but the tradition is as old as the school. A scene carved into the stone on the first campus building depicts a student looking up from a book at a distracting coed, oblivious to a galloping halfback on his blind side. In those days football was still a pastime of the educated classes. Later, when the sport’s popularity crossed social lines, football was said to provide a link between an elite institution and the common man. And it gave substance to Rice’s tenuous Texas identity.

But that was long ago. Rice’s last Southwest Conference championship came in 1957 and its last winning season in 1963. The Owls’ current losing streak—eighteen games—is the longest in major college football. Eight head coaches have presided over the misfortunes of the last twenty years, and crowds of less than 15,000 rattle around in the huge stadium.

Big-time athletics is an expensive hobby. The fifteen varsity teams (including seven for women) lose around $3 million a year and also drain another $1 million in tuition for scholarships. That’s enough to pay the salaries of most of the one hundred additional professors Rupp wants to bring in. One sports-minded trustee, boxing promoter Josephine Abercrombie, told the student newspaper that she has her doubts about football but that hers is a minority view on the board. Rupp, who came from the Ivy League, where universities give no athletic scholarships, is studiously neutral on the subject. But when I asked him about the traditional view that football plays a role in encouraging gifts to the university, he told me, “Many of the most vocal athletic boosters, if the truth be told, have not opened their pocketbooks very wide.”

On several delightfully carved capitals in the cloister of the chemistry building, completed in 1925, caricatures of professors from the earliest years of the institute peer down at passersby. One shows William Ward Watkin, the first chairman of the architecture department, sitting with his foot on the neck of a groveling student while others bow to him in fear. On another, administrators spin, measure, and cut the thread of knowledge like the Greek fates. A third shows a griffin with the face of a chemistry professor (later a dean), gripping a hapless student in its claws.

I always appreciated those comic architectural touches when I was a student. I sometimes wished that Kenneth Pitzer, a renowned Berkeley chemist who took over as Rice’s third president in my sophomore year, would take their lessons to heart. He came in with grandiose plans; the models for Rice, he told us, were “Stanford without a medical school” and “Princeton with girls.” A few years later he resigned to take over the presidency of Stanford, leaving Rice’s trustees bitter about their school’s being used as a stepping-stone and determined not to make the same mistake again. Seventeen years passed before Rice had another ambitious leader.

When I returned to Rice last February, I went back to look at the chemistry building and its carvings, which seemed to hint that right at the start the school and its leading lights were in danger of taking themselves too seriously. I found myself both excited about Rice’s future and worried about what it might bring. There’s no doubt that it is a better school now than it was 25 years ago. But I’d like to think that in another quarter century, the things that work best at Rice will still be the things that matter most—students and teachers.

Fryar Calhoun, a writer living in Berkeley, California, graduated from Rice in 1964.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Rice University

- Longreads

- Higher Education

- Houston