This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When photographer Laura Gilpin died in 1979, she bequeathed to Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum a vast archive of her art and life—about 50,000 prints, negatives, and documents—accompanied by a middling reputation as a chronicler of the American Southwest. But the history of American art is a still-sketchy drama awaiting a series of sweeping rewrites, and one of the dedicated revisionists working on the plot is Carter Museum curator and photographic historian Mami Sandweiss, who has spent the last few years reassessing the Gilpin legacy. Now we have Sandweiss’ newly published biography, Laura Gilpin: An Enduring Grace, and a companion retrospective exhibit at the museum through April 13. The result is a leading role for a player who had previously been relegated to the supporting cast.

Gilpin’s photographs are pure grace, but “amazing endurance” might be a less understated description of this remarkable woman’s life; compared with her, such celebrated art-biography subjects as Van Gogh or Gauguin come across as whining wimps. Gilpin, who was born in Austin Bluffs, Colorado, in 1891, went against all odds for the next 88 years. She was a self-proclaimed westerner at a time when even eastern Americans had to look self-consciously across the Atlantic for cultural validation. She was a photographer at a time when photography struggled for status as a fine art. Then, even after photography had established its legitimacy, she went against the grain with a romanticism that had become unfashionable among her colleagues. In a preliberated world she was independent with a doggedness that would wither a battalion of Gloria Steinems; never married, Gilpin not only financed her own art with an arduous schedule of commercial work but also for years supported an alcoholic father and then her ailing longtime female companion.

But the circumstances of Gilpin’s life gave her a profound vision of the American West. Her father was a Baltimore Quaker who, in Laura’s words, became an “instant cowboy” when he moved west in 1880 and who consistently lost money in such wild West enterprises as ranching and mining. Laura’s mother was the eastern yin to her father’s western yang, a St. Louis socialite who pined for the life she had left behind and packed her daughter off to the Baldwin School in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, and to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. When Laura, who had taken snapshots with her Brownie from the age of 12, decided on a career in photography at 25, she didn’t hesitate to go east and enroll in the Clarence H. White School of photography in New York.

Once a protege of Alfred Stieglitz, who pioneered the aesthetic canons of modern photography, White eventually opposed his elitist mentor with the conviction that the art of photography could be taught and that the elements of good photography could apply to commercial work as well as to fine-art photography. White became identified as the guru of pictorialism, a style of photography that emphasized the formal arrangement of shapes over precise mechanical detail. At its worst, pictorialism superficially aped painting and printmaking with cloying, out-of-focus parlor poses, but at its best, the pictorial style had an aggressively modern, abstract pith.

At the White School, Gilpin was drilled in the basics of formal composition by instructors such as painter Max Weber, who was one of the first Americans to absorb the lessons of Picasso and Matisse. Gilpin’s exacting sense of structure was evident early; in The Prelude (1917), which was shot in the soft-focus, soft-lit pictorial style Gilpin acquired from White, a trio of musicians is posed with the elegant solemnity of classical sculptures.

Gilpin contracted the flu during the epidemic of 1918 and returned home to Colorado, where, following her recovery, she began her lifelong vocation as a commercial photographer. Dignified but uncannily familiar portraiture became her bread and butter—her sitters varied from actress Lillian Gish to U.S. Supreme Court justice James C. Reynolds—but Gilpin expanded her range as a photographer by never refusing anything that would pay the bills. She shot such prosaic subjects as Denver high rises and later, during a stint as a photographer for Boeing during World War II, took the first aerial shots of the B-29 bomber.

It was apparent from such early works as Cathedral Spires (1919), where eroded rock towers loom with Gothic majesty through a pictorialist haze, that Gilpin’s soul was firmly rooted in her native landscape, but a trip to Europe in 1922 provided the epiphany that was to bring Gilpin’s art home to stay. As she photographed Chartres Cathedral with rapturous evocation of the textures of centuries-old iron- and stonework, she realized that a great cultural epoch was passing unnoticed in her own back yard. “The romance of the old West vanished so fast and so few ever did anything with it,” she wrote in her journal. “Does it make you realize the importance of art, and how the main knowledge of history is thru art alone.”

While painters like Remington and Russell had, a few decades earlier, celebrated the romance of hard men against a hard land, Gilpin found her Western art inspiration in the more harmonious accommodation of Indian tribes like the Pueblo and Navaho to a landscape that could nurture a complex, spiritually rich civilization. Round Tower, Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde, Colorado (1925) endows Indian ruins with a biblical grandeur, while in Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (1931) the crumbled and eroded walls, serpentining in the desert, echo the centuries.

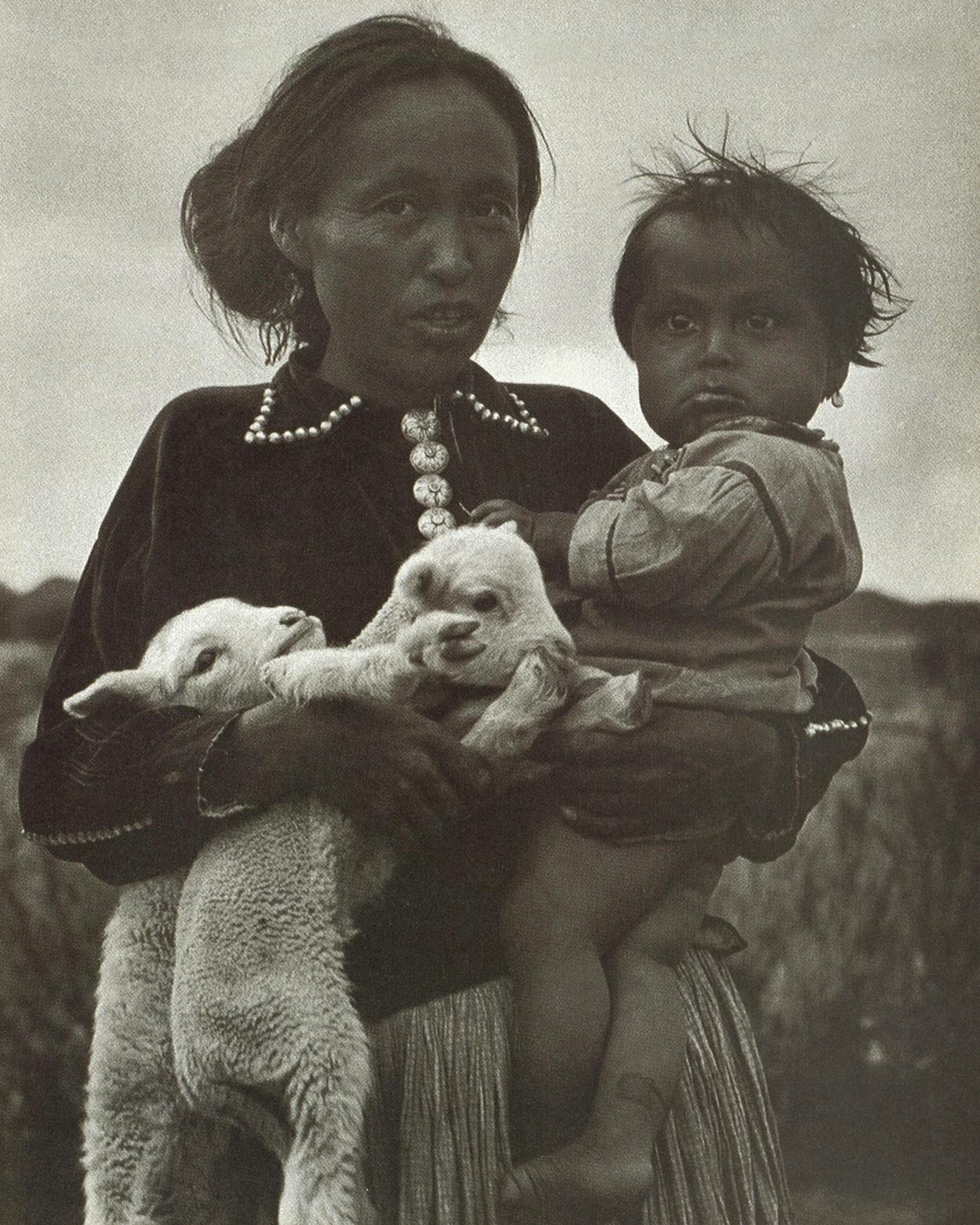

Initially Gilpin had difficulty penetrating the implacable facade of living Indian culture; a series of portraits of the Pueblos taken in 1925 is little more than a collection of awkwardly posed picture postcards. But in 1931 Gilpin’s lifelong companion Betsy Forster took a nursing job at the Red Rock, Arizona, Navaho Reservation, and Gilpin’s camera gained access to a secret culture that had endured in spite of the hammer blows of white conquest and the onrushing twentieth century. Gilpin visited the hogans and attended the rituals that wove together the Navaho spirit and the forces of nature, and her sensitivity permitted her such penetrating portraits as Setah Begay, Navaho Medicine Man (1932)—he evidently has the Force with him—and Navaho Woman, Child, and Lambs (1932), in which a young mother clutches new life with casual wonder while her son stares as formidably as an infant Caesar. Those Navaho portraits also reveal how far Gilpin had come from her pictorialist origins. After accidentally dropping her soft-focus lens in the Atlantic on her way to Europe in 1922, she had gradually turned to more sharply focused, straightforward images, and by the early thirties she had successfully merged the pictorial emphasis on classic composition and romantic allegory with a candid appraisal of everyday life.

Gilpin admired above all the serenity and patience of the Navaho, qualities that she would herself need for the rest of her career. The Depression hit most artists hard, but Gilpin got a triple whammy: her commercial assignments dwindled, her now-widowed father became a full-time dependent after his business went bust, and her style of photography began to go seriously out of fashion. The Farm Security Administration photographic survey, which provided both Depression-era employment and the first starring vehicle for such twentieth-century masters as Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, and Walker Evans, fostered a graphically contemporary, unremittingly detailed style of photography that was to dominate the medium for many years. Saddled with the stigma of her pictorialist style and unwilling to apostatize entirely, Gilpin became unfairly characterized as a mushy romantic.

Gilpin struggled through the Depression, even resorting to running a turkey ranch during the late thirties, and after the war she plunged into a trying series of major books. In Temples in Yucatan, published in 1948, Gilpin portrayed the Mayan ruins at Chichen Itzá as a New World Thebes, the seat of a venerable culture that still had its resonances, as she pointed out in her text, in modern Indian life. With the book The Rio Grande: River of Destiny (1949) Gilpin expounded on another favorite theme, the effect of landscape on history and culture. Rio Grande showcased Gilpin’s deft landscape technique; in Storm From La Bajada Hill, New Mexico (1946) she captured the intricately textured underside of a rain cloud with a spontaneity that would have escaped a more deliberate technician like her friend and admirer Ansel Adams. Rio Grande Yields Its Surplus to the Sea (1947) is an almost oriental abstraction, the river a fluid silver glyph joining a sea that shimmers like a mirage before disappearing into the sky.

Gilpin drew the broad scope of her interests together in the book The Enduring Navaho, a project she began in 1950 that essentially consumed the last two active decades of her life. She carried on with that magnum opus despite the cancellation of her contract by her original publisher, rejections from numerous other publishing houses, the necessity of caring for an ailing Betsy Forster, continued interruptions to pursue desperately needed commercial work, and her own advancing age. Gilpin bottomed out in 1962, when she realized a net loss of $350 for the year, but the next year her salvation came in the form of Mitch Wilder, director of the two-year-old Amon Carter Museum and a friend of Gilpin’s since the thirties. Wilder connected Gilpin with the University of Texas Press, which agreed to publish the book, and the seventy-plus-year-old author charged down the homestretch, pausing to sell some jewelry to support herself while she wrote the text.

The Enduring Navaho, finally published in 1968, was both a sublime fusion of Gilpin’s romantic notions of American Indian culture and a realistic evaluation of the effects of modern American culture on that ancient heritage. She unflinchingly recorded the changes wrought by New Deal programs on tribal life; her subjects now wore contemporary ranch attire, studied English in classrooms, and received justice beneath a portrait of George Washington. Gilpin found her theme not only in the persistence of tribal crafts and ceremonies but also in the stoic endurance of the Navaho as they struggled with a new world. In A Navaho Family (1950) an aging couple and their three young children pose in front of an American flag that is draped over the coffin of the oldest son, killed in World War II; each face is a landscape of suffering, acceptance, and quiet pride.

The Enduring Navaho brought Gilpin some well-deserved recognition in her eighties, but this powerful new retrospective and engaging biography—Sandweiss does a particularly good job of tying together Gilpin’s life and art as well as placing her subject against a broader perspective of twentieth-century photography—emphasize how seriously underrated both Gilpin’s eye and intellect have been, even after that partial, sadly belated resuscitation. Few twentieth-century photographers can match her range over both landscape and portraiture, and no painter or photographer has surveyed the American West with greater formal elegance. Though she was doing some of her best work in the mid-twentieth century, Gilpin was a true Western artist in the tradition of a panoramic landscapist like Thomas Moran as well as a cowboy artist like Remington. It’s just that Gilpin, unfettered by such male-intensive fantasies as manifest destiny, was able to appreciate the subtle romance of a Western culture that will, in the long view of history, prove to be more enduring than the few decades of shoot-’em-up that pass for our Western heritage today.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth