This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I used to rent a garage apartment from a ninety-year-old doctor who told me that in his professional opinion the Big Mac was a “perfect nutritional unit.” Several evenings a week I would see him doddering along the driveway with a big grin on his face, holding his cowboy hat in one hand and a bag from McDonald’s in the other. His wife would meet him at the back door, and together they would silently ascend to their dim upstairs dining room and fulfill their nutritional requirements.

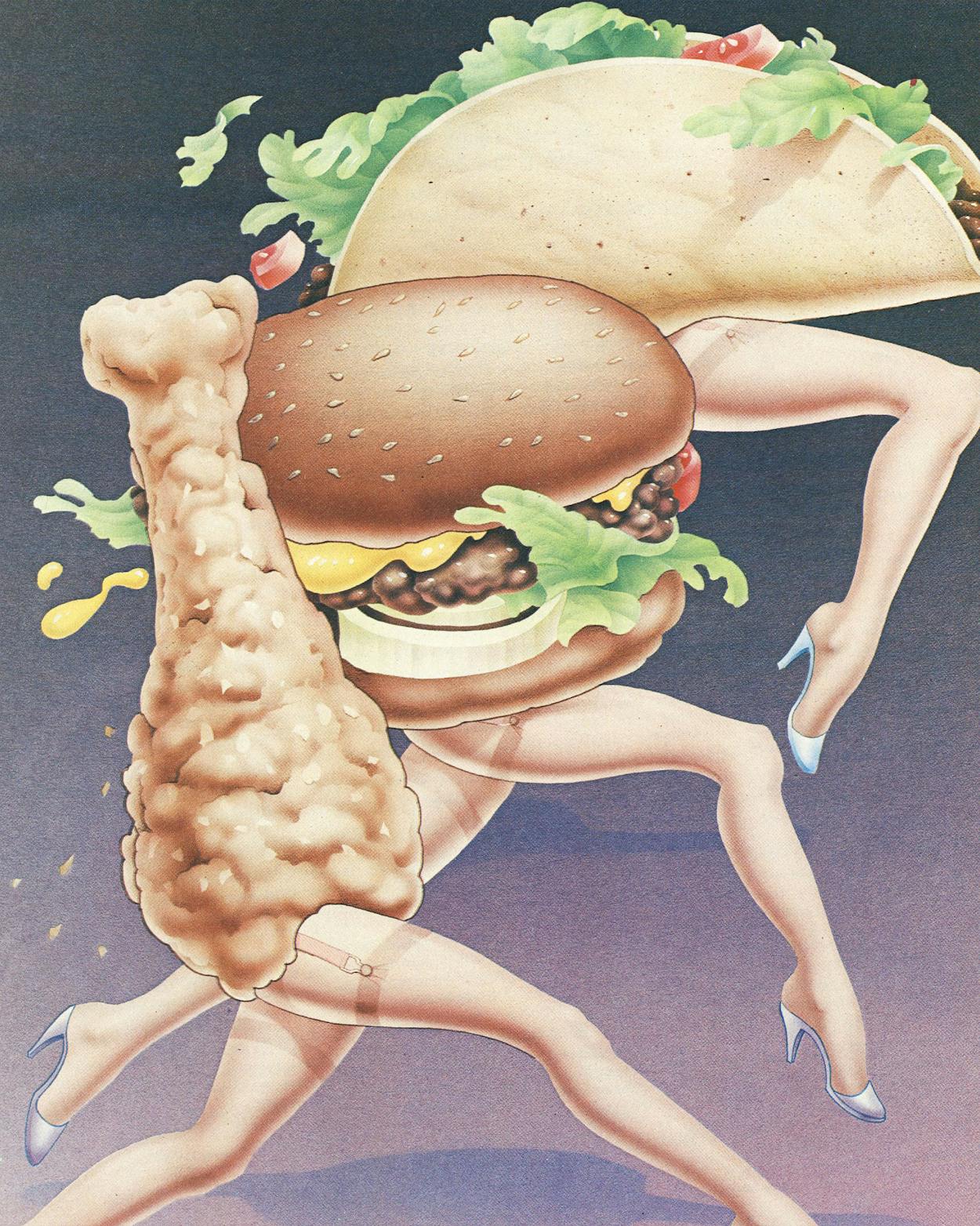

I was invariably touched by this scene, which seemed to me a fast-food version of courtly love, but then I’m a romantic about an institution that many people consider the scourge of civilized dining, if not of civilization itself. I like just about everything about fast food. I like to sit in the dining room of Gargantua Burger, relaxing in a booth made of injection-molded plastic and stainless steel, watching the sullen counter personnel in their perky uniforms processing orders while I open up another Serv-A-Portion™ packet of reconstituted lemon juice and pour it into my iced tea. I’ve heard it said that the color schemes of fast-food establishments are subliminal signals, meant to convey a sense of hospitality of only a limited duration, but I find the bright oranges and yellows much more soothing than the subdued interior of a mainstream restaurant.

In a more active mood I might wheel into the drive-thru lane, give my order to a fiberglass clown with a speaker in its nose, pick up the food, and eat it without turning off the ignition, with all that horsepower still rumbling beneath me. Such a maneuver creates the illusion of predation, of active procurement of food.

There is no point in arguing that fast food is not vulgar. One has only to think of the homogenous blandness of the product, of all the living beasts that are stunned, shredded, and re-formed into harmless-looking protein modules, the top-of-the-food-chain philosophy, the dubious nutritional value. It is a matter of taste, though, whether one finds this vulgarity vibrant or decadent. I don’t like urban blight any more than anyone else, but I must admit there have been times when, hungry and tired, driving through a strange town, I was thrilled to see before me the Central Franchise District—cheap, accessible, certifiably mediocre food as far as the eye could see.

If Walt Whitman were alive today he would eat fast food. He would scarf down his hamburger, french fries, and Coke, then lean back in his chair with his arms folded across his chest and take it all in: the construction workers with lock-back knives in sheaths on their belts, children studying their free puzzle placemats, bureaucrats, beauticians, students; people who eat off-handedly, with splendid indifference, who would not know a Cuisinart from a washing machine.

Even people who despise fast food hold passionate opinions about which chains have the best hamburgers or chicken or tacos. In the field of hamburgers, I find it hard to imagine that any reasonable person would question the superiority of Whataburger, a Texas franchise that has recently begun its conquest of the rest of the nation.

I first encountered the Whataburger in Corpus Christi, the city where it originated. One day the mother of one of my fifth-grade classmates appeared in the classroom at lunchtime and presented her son with a white paper bag stained with grease and giving off a warm fragrance that seriously distracted the entire class. Out of the bag the kid pulled the biggest hamburger I had ever seen.

“What is that?” I asked him.

“It’s a Waterburger,” he said. “It weighs a quarter pound and it costs thirty-five cents.”

I watched longingly as he ate it. The fact that I thought it was called a Waterburger only added to its mystique.

A few days later I ate my first Whataburger at one of its three Corpus Christi locations. During this period Whataburger architecture was rather extreme, featuring a giant incorporated into an orange-and-white A-frame building several stories high. One walked in and gave one’s order to an employee above whose head was a sign that read, “Please tell me—how many you want! Next man will ask—how you want ’em.’’ The next man, slapping the meat down on the grill, would inquire, in the most courteous manner, “all the way on your double-double?” It was not exactly fast food, but there was a certain satisfaction in dealing with craftsmen.

As the operation began to expand, the A-frames were replaced by more tasteful buildings, the preparation of the food became more covert, the prices soared, and the employees were made to wear see-through plastic aprons that gave them the look of highly specialized medical technicians. Through all this the quality of the basic Whataburger has remained consistent. I doubt if it bears much analysis—it’s just a good greasy hamburger—though a Whataburger spokesman I talked to was very proud that the hamburger meat was never frozen, but was instead freshly ground in the company’s two processing centers in Corpus Christi and Fort Worth, and cooked to order. “Our concept is that no Whataburger is cooked until you up and order it, as opposed to the precooked, prewrapped, hand-it-to-you-from-the-warmer concept.”

That would be the McDonald’s concept. I will admit that McDonald’s makes excellent french fries, but their hamburgers, in all their various manifestations, taste like mulch. Perhaps this is because, as the McDonald’s Beef Brochure says, the meat is cryogenically frozen “to preserve freshness, texture, wholesomeness, and taste in an absolutely uniform way.” To be fair, the quality of the food is a secondary phenomenon at McDonald’s, which seems more interested in providing its clientele with some form of spiritual nourishment. If one believes the ads, McDonald’s is a place where family love and racial harmony abound, where beautiful post-adolescent girls croon “You, you’re the one” to lonely businessmen and frazzled Little League coaches. One is not a customer at McDonald’s, one is a communicant, a subscriber to a system of values.

Perhaps it is an extension of this world view that makes McDonald’s the only fast-food establishment that is unprepared for individual tastes. Order your Filet-o-fish without tartar sauce or your Big Mac without mustard and you will be stranded on the outskirts of McDonaldland for twenty minutes while the faithful file by and are promptly issued their Styrofoam containers.

Wendy’s is more flexible. The service is very efficient and accommodating, and the hamburgers, freshly ground and formed in situ by a “patty machine,” are not bad at all. The meat in the hamburgers is square, an interesting diversion. “The reason that it’s square,” a Wendy’s representative told me, “is that Dave Thomas, the founder and chairman of the board of Wendy’s International, wanted a custom hamburger. He wanted the meat to hang out over the bun.”

Of the other hamburger franchises, Burger King, Burger Chef, Royale Burger, Jack in the Box, little needs to be said. None of them inspire me to any enduring observations, though I will say I miss the big inflatable chef that used to hover over the Whopper Burger at the corner of Hancock Drive and Burnet Road in Austin. The other fast-food beef products—tacos, roast beef sandwiches—lie outside the field of my expertise.

Fried chicken is another matter. I know about that and am, in fact, a casual student of the marketing ploys used to take the consumer’s mind off the fact that what he is eating was once the limbs and working parts of living chickens. Unlike hamburger, chicken pieces cannot easily be disguised, hence we have euphemisms like “drumstick” for “leg.” At Kentucky Fried Chicken, breasts were once referred to as “keels” in an effort to keep the customers at a polite distance from the carnal enterprise, from the vision of millions of naked chicken carcasses being processed through the Colonel’s maw.

Colonel Sanders himself has passed into fast-food iconography, a life-size cardboard cutout no more substantial than the Burger King or Ronald McDonald or Tee and Eff, the two Tastee Freeze totems who are, apparently, animate dollops of ice cream. With the Colonel’s original Eleven Secret Herbs and Spices recipe joined now by Crispy- and Barbecue-Style chicken, with his face printed on the lids of an execrable line of products called “The Colonel’s Little Bucket Desserts,” he is the closest thing to a tragic figure one is likely to find in the world of fast food.

The chicken itself, whether original, crispy, or covered in barbecue sauce, is rather dry but durable. The service is generally prompt, but I have no kind words for the gluelike whipped potatoes or the aerated square of dough that is referred to in-house as a “roll.”

Kentucky Fried Chicken’s principal competition, Church’s, is slick and streamlined. The chicken is crispy, plunged before your eyes into bins of boiling fat. (Is it my imagination, or do all Church’s employees have the hair singed off their arms?) Unless the chicken has been sitting under the heatlamp for a while it is usually still glistening from its immersion and too hot to eat. The facilities for leisurely dining are minimal, the few table and chair combinations reminiscent of unsafe playground equipment. And if one hits Church’s at the wrong time—say, around lunch and dinner—the chicken may be depleted, since Church’s personnel are notorious for not planning ahead. “Uh, that’ll be fourteen minutes on that chicken, sir,” they will tell you, immediately removing their operation from the arena of fast food.

Both companies insist their chicken is never frozen. In the case of Church’s, the “birds, as we like to call them,” are delivered whole, then cut up at each store into eight pieces and marinated in a secret solution for a “semi-secret” amount of time. Kentucky Fried Chickens-to-be are delivered to each outlet already dismembered into pieces that are, on the average, smaller than Church’s.

Only those people whose doctors have placed them on unbalanced, high-cholesterol diets should frequent fish and chips establishments. You can feel your arteries begin to harden as soon as you walk through the door. Everything is fried in the same vats, fish and shrimp and terrible french fries and congealed globules of grease called krispies that look and taste like packing material. I must confess, though, that Long John Silver’s, one of the most obnoxious places of business on earth, manages to produce delicious fried fish. The thing to do is batten down your imagination and try not to notice the pirate hats and salt-stained walls and door handles that are shaped like cutlasses. Get your fish, walk the plank, and cut out.

The fish at Alfie’s is not equal to that at Long John Silver’s, but the atmosphere is less relentless. I’ve never eaten at Arthur Treacher’s Fish and Chips, and as I grow older my desire to do so seems to be waning. I once stopped at another franchise called H. Salt, but when I heard pirate music over the loudspeaker (“Doodle doot doot doot”), I got embarrassed and had to leave.

The fast-food industry has its unacceptable conceits—the fried pie, for instance—but in general it needs no defense. It may seem now like a rapacious, uncontrollable phenomenon, but already, along certain overdeveloped commercial thoroughfares one notices the vacant hulks of bankrupt franchises that were once thought invincible. Maybe this has something to do with the gas shortage, or with poor marketing decisions, but it is just as likely to be the normal course of things. Fast food won’t be around forever, a thought that both comforts and saddens me. I’ll be among those who cherish the memory of driving down the highway with a Coke nestled between my legs, a double-double in my hand, and the secure knowledge that should I get hungry again, there will be Dairy Queens at forty-mile intervals all the way to the horizon.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics