This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

With my jacket over my shoulder and a paper bag containing a change of clothes under my arm, I got off the bus in Nuevo Laredo. It was around nine at night, and my plan was to cross the Rio Grande into the United States without papers—a trick that involves breaking the law on both sides of the border. Had I known what was in store for me, I would have thought twice before deciding to go. But my circumstances didn’t offer me much choice.

Five months earlier I had married a young university student in Mexico City. Her graduation was still a year off, and the only job I’d been able to find, as a parking-lot attendant, didn’t pay enough to meet our bills. My hope was that after working in the U.S., I might return home with enough savings to make a down payment on a house in Mexico. When I left for Nuevo Laredo last November, my wife stayed behind with her parents in Mexico City.

Going to El Norte was practically a tradition in my hometown, a village in the mountains of Oaxaca State. A few of my townsmen had gone to the United States during World War II, and even more went after 1950, when rumors of the bracero program reached the village. In those days—ten years before there was a highway from our village to anywhere else—the town’s little merchants bought such goods as we produced (corn, beans, piloncillo, coffee, and achote), loaded up their burros, mules, and horses, and rode for three days to Oaxaca City, where they sold their merchandise. On the return trip, they carried manufactured goods, tools, clothing, cooking utensils, and candy, which they hawked from town to town.

One of those merchants heard that there was a way to work in the United States, a report that most people didn’t believe at first; the merchant and two of his friends decided to try. The three visited the American embassy in Mexico City and found that they would need their birth certificates in order to apply. They got their papers in order back home and returned to Mexico City. After a wait of two weeks, they were contracted to work in California. During their months in the U.S., they sent home postal money orders, which their families cashed in Oaxaca City. Everyone in the village was impressed when the three men came home at last, bringing with them boxes of foreign goods, especially clothing.

Their experience persuaded others to go, though not everyone was as lucky as the first three had been. Some braceros were contracted only for short periods of time, and before long there were more people across Mexico who wanted to become braceros than there were openings. The situation provided an opportunity for men who, for a fee, bribed Mexican officials to include their clients’ names on the list of those chosen to work as braceros. When the bracero program ended in the mid-sixties, those men, called coyotes, simply began performing its functions themselves. They found employers in the United States and brought Mexican workers to them illegally. When that system ran into difficulties, due to Immigration and Naturalization Service raids and farm mechanization, the coyotes turned to what they do now: delivering Mexican workers to American cities, where, as often as not, jobs are hard to come by. But even today a bad job in the United States pays a good wage by Mexican standards.

The bus station’s big, bright waiting room was crowded with people. I figured that I would catch a taxi and look for a hotel downtown where, people in my village said, one could make contact with coyotes. As I was heading out, a short, thin man in jeans and a sport shirt greeted me and asked where I had come from. When I answered Mexico City, he exclaimed that he too was from there. I told him that I intended to go to Houston because I had a friend living near there, but that before I could go, I needed to find a coyote.

“Are you looking for a particular coyote? Did anyone recommend one?” he asked.

“No, I don’t know of any,” I said.

“Well, I work for the best and most badass coyote in town,” he declared. He said that his coyote was ready for a crossing at dawn of some forty “goats” (wetbacks) bound for Houston. The amount I had to guarantee, if I wanted in on the deal, was $450 for the trip to Houston, plus 4000 pesos (about $27) for the rowboat ride across the Rio Grande.

“There’s no problem about the money,” I told him.

“Good. In less than eighteen hours you’ll be in Houston,” he said. “But tell me, do you have somebody who will be responsible for paying us there? And if you do, how can we prove it? Can you give us a telephone number we can call in Houston?”

“There’s no problem about the money,” I insisted. “As soon as we get to Houston, you’ll get the payment you ask for.” We walked to the men’s room so I could wash up. I didn’t want to tell him that I was carrying enough money to pay him. Of the $650 that my friend had sent me, $550 was sewn into the lining of my jacket. The rest was in my billfold.

My friend, who has lived in Texas for years, had made it clear that it was better not to disclose to anyone—above all, La Migra (Immigration)—his telephone number or address. His advice, which I followed, was to memorize his phone number in case I needed it but to give it to no one.

I had hidden the money because I was afraid of being robbed or cheated, like my father had been during the era of the bracero program. He and two others from our village were swindled by a coyote in Juárez who promised them contracts as braceros. Two days after they paid him, they read in the newspaper that he had been killed in the red-light district. They were left stranded without a cent.

They looked for work, but jobs were scarce and wages low. A few days after they learned of their coyote’s demise, they had to give up their boardinghouse room. Fortunately, the old lady who owned the boardinghouse softened her heart and let them sleep in the corner of a hallway. As the days passed, their diet came to consist of a single meal a day and then was reduced to a small bowl of peppers in vinegar and a handful of tortillas. One time, after two days without food, the three of them split a slice of stale bread. So as not to lose even a single grain, they cut it with a razor blade.

All of this came to my mind while I washed my face and listened to my new acquaintance praise his jefe, Andrés Nares.* He told me that his jefe was effective and invulnerable to the law because he had paid off the Mexican police at the federal level. And, the thin man went on, Nares’ outfit treated the goats better than anyone else did, even providing a house where they could wait until they crossed. Other coyotes made their clients sleep in the open and did not supply food. He stressed his jefe’s generosity toward him too—his jefe didn’t pinch pennies when the two of them went drinking. As I was drying my face with the sleeve of my jacket, I asked if I had to pay for each crossing of the river or only for a crossing made without incident.

“No, no, nothing like that!” he exclaimed. “If ten times they catch you, ten times we’ll cross you for the same payment. Don’t you worry about that. The jefe is here right now. Let me introduce you to him.”

We walked to the terminal’s diner, where the thin man pointed out a group of three people, each with a can of beer, seated at a table. “Do you see the gentleman who is wearing a cowboy hat? Well, that’s Andrés Nares, compadre. You need only say that you are a client of his and even the police will leave you alone. If you were out in the street now without a car, the police would grab you as you went around the block, and they might rob you. But if you tell them that you’re with Andrés Nares, they will take you to our house themselves. Wait here. I’m going to tell the boss that you’re going to Houston.” He went to the table and spoke to Nares. Then he motioned for me to join them.

Andrés Nares was wearing a yellow T-shirt that read, “Roberto Durán, Number 1.” He had a handsome face, clean-shaven except for a thin moustache, with skin that showed the birth of those wrinkles that mark a man who is nearing fifty. There were several tattoos on his arms; the most outstanding of them was a tattoo of the bloody head of Christ, crowned with thorns. Nares asked me in a dry and untrusting tone where I was headed and if I had someone who would be responsible for me. I answered as before.

“Then I should take him?” the thin man asked. Nares nodded.

Outside the bus station, the thin man and I got into the back seat of a station wagon. We had to wait for its driver to show, he said as he opened two beers from a six-pack on the floor and handed one to me. He asked my name.

“Martín Pérez,” I told him. I didn’t want him to know my real name.

“My name is Juan,” he said. “I’m not going to tell you my last name, because I don’t know you. But with great pleasure I’ll tell you my nickname. You can just call me México.”

As I sipped my beer, México drank another one, then another, talking all the while. He said he had been a taco vendor in Mexico City; hence the nickname México, like the names Tex and Dallas are used by Texans. He had done well in that business, thanks to a car his boss had loaned him; with the car he was able to station himself at busy places, like soccer fields. But after his boss sold the car, México ran onto hard times and had to ask a friend for a loan of 5000 pesos.

His friend loaned him twice that much, though México protested his generosity. A month later, he said, the same friend arrived at his house in a luxurious new car. “The first thing that hit me,” México said, “was that he had come to collect. But, to my surprise, he told me to forget the debt. ‘If you’ll help us,’ he said, ‘things will go better for you.’ ” México asked how he could help, and his friend drew an automatic pistol from his waistband. He and another conspirator had planned some holdups, and they offered México a new .38 pistol if he’d join the scheme. México agreed. Everything went well, he said, bragging of takes amounting to 500,000 pesos from simple holdups.

But then the three men met up with the son of the owner of a slaughterhouse. He wanted to rob his father’s firm, and he knew how to do it. He said that his father was swimming in money but was too cheap to spend any of it, even on himself. The four men, at the son’s direction, entered the office of the slaughterhouse one afternoon just as the owner was counting out the receipts on his desk. When he realized that he was being robbed, he reached for a pistol, and the holdup crew fired upon him. Even the man’s son fired, México swore. They made off with 2.5 million pesos—México’s take was half a million—but before long, investigations began. When the son was arrested, Mexico decided to head north.

“I had enough to pay the coyote,” he told me, “and after two attempts, I was in Houston. But I was able to stay only a month. One night as I came out of a bar drunk, the police grabbed me. Soon I was back in Nuevo Laredo with no more to my name than ten thousand pesos. Not being able to go back to Mexico City or to cross again, because I had nobody to pay for me, I asked the man who now is my boss, Andrés Nares, for a job. As you can see,” he said with pride, “I’m a runner. They call us that because we are always running behind those we suspect want to go to the United States.” I asked him how much he earned as a runner.

“Of the four thousand pesos that you’re going to give me for the boat, two thousand are for me. I make that much on every client I take to Nares’ house.”

“Then by now you must have a lot of money,” I commented.

“Well, yes,” he said, “I’ve made a lot. But as for having it, I don’t have it stashed away. Because, well, what good is money? To spend!”

“How many clients do you recruit a day?” I asked.

“It varies. There are several of us runners. You can ask for Gums, Shell, Dog, or Mosquito—everybody knows them. Sometimes I get together five clients, sometimes none. In short, it varies. Understand?” México interrupted his explanations to point out a car that was parking in front of the terminal. “That car without the license plates,” he said, “belongs to the federal undercover police. It won’t be long before Andrés Nares comes outside to talk to them.”

As he said, in less than a minute Nares came out, walking toward the car. “See!” México exclaimed. “What I told you isn’t any lie. That son of a bitch is well connected!” A few seconds later a middle-aged man appeared and got behind the wheel of our station wagon. Without saying anything, he started the car and we left. “This fool,” México said, pointing at the man in the front seat, “is the one that they call Shell.”

The House of Andrés Nares

Andrés Nares’ house was located on the fringes of Nuevo Laredo. The street was filled with puddles because the water lines were broken. As I got out of the station wagon, México told me to go to the patio, in the middle of the concrete house. “Be careful,” he said, “and don’t step on the guys who are sleeping there.”

The patio was about fifteen feet square; on the side that opened to the street a crooked wooden fence, almost fallen down, marked off a piece of ground that somebody had tried to make into a garden. There wasn’t a roof—just the clean, starlit sky.

People were stretched out all over the patio, and before finding a place to lie, I counted 35 of them. I lit a cigarette and sat down on a heap of cement blocks, where I intended to sleep. “Have you got cigarettes?” one of those in the darkness asked. “Give me one.” Within seconds others gathered around, and in a few minutes my pack was empty. But I wasn’t worried; in my paper bag I still had seven packs from a carton I’d bought the day before.

I couldn’t see anyone who had a blanket—I covered myself with my jacket. For a pillow, I used my bag of clothing. The warm atmosphere was permeated by the smell of grime, dust, and sweaty feet, and the snores of sleeping men could be heard. First one and then another changed position. I slept fitfully, even though I felt the strains of having stayed awake on the bus trip and waiting tensely for the word—any minute now—that it was time to leave.

But daybreak came without such an announcement. I got up and went looking around. The place where we were gathered was barely fifteen yards from a big garbage dump in whose center enough water had collected to make a small lake. Big cars without tires rested on wooden blocks on both sides of the unpaved street. Across the street from Nares’ house was a miserable shack and, to one side of it, a cement patio that seemed to be a repair shop. There were two cars on the patio, one with its motor out, the other with its transmission on the patio floor. Beyond the patio was a pen that held four medium-sized pigs. People from Nares’ house went back and forth to the shack, as if it belonged to them or to Nares. In Nares’ house the rooms surrounding the patio that was our bedroom had been constructed haphazardly. The doors were made of poorly cut wood, as were the windows with their torn screens.

Next to Nares’ house and near the street was a pile of sand, where I went to sit. Soon another of the group, still rubbing his eyes, saw me smoking and came to ask for a cigarette.

“When did you get in?” he asked as he sat down beside me. He told me that he was headed to Dallas, where the coyote would charge him $600. All of his clothing needed a cleaning. His shirt collar showed the grime of several days, his graying hair was unwashed and disheveled, and his teeth were yellowish. His reddened eyes expressed tiredness and boredom, and so did his voice. “I’ve been waiting for six days,” he said.

When I told him that I’d been promised that we would leave before sunup, he answered, half scoffing, half moaning, “They tell everybody that. They always do it so you’ll go with them. The day before yesterday they sent thirty people, and it seems it must have gone well for them, but there are always people here.”

“Is this the first time that you’ve gone to the U.S.?” I asked.

“¡Que va! For ten years I’ve been going and coming. Every two years I go to Guanajuato to see my family.”

I was surprised to learn that he was only 33. With his gray hair and grizzled beard, I would have guessed that he was at least 45. “Don’t you get bored with waiting?” I asked.

“I’ve got experience, boy!” he told me. “What you need here is patience. Some people come with the idea that they will cross over soon, and it does happen that way, but not very often. It’s just a question of luck. Before long,” he continued, “you’ll learn that some people have been waiting a month. Sure, they’ve carried them across, but La Migra has caught them. They come back to be carried across again, until they make good.”

Later, when the sun had risen, those who had slept inside the cars across the street walked around a bit and then looked for a place to sit on Nares’ patio. Those who had slept on the patio got up lazily. The same boredom and lack of cleanliness had taken hold of them all.

When the sun was directly above the patio, clouds of flies began buzzing out of the carpet that covered the patio floor. Two fat women, each about thirty years old, came out of a room carrying baskets filled with dirty clothing. They headed for the sink that was in one corner of the patio.

“Those who got in last night,” hollered a man I recognized as Shell, “come to the office!”

Five or six of us bunched together in front of the room that was the office. The door squeaked as we opened it. The room was small. There was only an unmade bed with box springs and a dressing table, on top of which sat a telephone, an alarm clock, and some beer cans. Nares came in from another room, the marks of a hard night on his face. “You all came in last night?” he barked without greeting us. “Did they tell you how much you have to pay? Come up here one at a time. The rest of you, wait your turn outside.”

When my turn came, he explained with great flourishes what México had told me the night before and asked who would be responsible for me in Houston.

“An old friend,” I answered.

“Have you got his telephone number so I can call to make sure that he knows you and will be responsible?”

“I don’t have the number with me, but I’ve certainly got a way to pay you,” I said, trying to convince him.

“I’m getting to be an old man,” he said sarcastically. “I’m wise to all kinds of tales. There’s always someone trying to pull a fast one. I’ve sent people who have sworn by their fathers and mothers that they would pay when they got there. Then, when they get in, they say they don’t have anything. We have to be sure who will pay.”

“My buddy will pay,” I assured him, “and he didn’t want to give out his telephone number because he can’t have trouble.”

“This isn’t a game!” Now he was irritated. “You have your buddy give you the telephone number, and if you want to stay here, you need to pay the four thousand pesos for the boat.”

There was nothing for me to do but pay the 4000 pesos and get in touch with my friend. I didn’t want to use Nares’ telephone because I didn’t want anyone to overhear anything about the money I was carrying. I needed to get to a telephone booth downtown, and I mentioned my problem—but not the money—to some of the others.

“If you go downtown, be careful. The police are real jija de la chingada,” one man warned me.

“Well, if you tell them you’re a client of Andrés Nares, won’t they leave you in peace?” I asked.

“Who are you going to believe?” he said, as if my credulity was a lamentable thing. “These guys here, as much as the police, are thieves. They’ll shake you down and rob you. Be careful. We’re among dishonest men.” I decided to wait.

The heat grew worse after midday, and my companions spread out, looking for shade. Some played cards; others chatted. A few turned up with bags of bread, cookies, and Coca-Cola. I asked what time the owners of the house passed out food. “Only God knows,” one of them said. “There’s never a fixed time. It can be now, in a little while, or at night.”

Most of the fifty in our group were farm workers from states in northern Mexico, but a few men were from the south. We had different destinations: Houston, Dallas, Miami, Chicago. Only one in ten was going to the United States for the first time.

Men in another group were discussing coyotes and the dangers ahead. A young, thin man with Indian features said that he knew of a coyote in Nuevo Laredo who collected his fee and took people across the river but then left them there in the brush. As many as forty men would wait there for days, being fed only one sandwich a day. Before the coyote finally moved them further north, a lot of them set out on their own, and Immigration agents usually caught them hitchhiking or trying to get on freight cars.

One man gave another reason for not striking out on our own: bands of thieves worked the riverbanks. When men crossed alone or in small groups, the thieves attacked, sometimes drowning their victims in the river. “And there’s no one to claim our bodies,” someone moaned. “We’re so far from home that our families wouldn’t even know what had become of us.”

“The good thing about coyotes,” another man said, “is that they can’t make any money off dead clients.” Most men in the group seemed to agree—a coyote was good insurance against the dangers of going north.

At around three o’clock we heard a voice cry out, “Lunch!” We hurried toward one of the rooms, and everybody tried to be first in line. The dinner was a bowl of soup with potatoes and refried beans. Everybody got his portion and then looked for a place to eat.

México arrived with two young women, one of them carrying a baby in her arms, and a man. Shell stepped out of his room about then, and we circled around, asking when we would be leaving. “About dawn,” he said, “but only twenty-five will be going.”

An hour later a black car with tinted windows and no license plates pulled up to the house. The two muscular men inside the car didn’t get out, but Nares went out to them. A moment later he returned to his room, then went back to the car and handed the driver a little packet. He shook hands with the two men through the car window, and they drove away. “Those were the undercover cops,” one of my companions said. “They came to get their take.”

Shell came out of his room again with a notebook and called out 25 names. He took those men aside and told them that everything was ready. The news excited us all, but since my name hadn’t been called—I hadn’t turned over the telephone number—I decided to rest. For two nights I had slept badly, and I was tired. I stretched out on a bench by the wall, using my jacket and sack of clothes for a pillow. The comfort I provided for myself was something I vividly regretted as soon as I awoke two hours later. My jacket and change of clothes had disappeared.

The unexpected loss made me sink into depression. My money was gone with the jacket, and though I asked everybody who had been near if they had seen someone steal my jacket, no one admitted to knowing anything. I looked in every corner, at every face, to see if I might find some suspicious sign. But it was useless. The loss robbed me of sleep again.

Around two o’clock in the morning, the list of 25 names was called again. Sixteen men were loaded head to toe, like sardines in a can, into the station wagon. The other nine were packed into a big blue car that had been on blocks, without any tires, the day before; three of them were put in the trunk. In minutes the group was gone.

When sunrise came, after one of the longest nights in my life, I decided that for me there was no recourse but to call my friend and tell him what had happened. I walked downtown, a little apprehensive about being robbed of my last $100, and found a long distance office. My buddy was angered by my carelessness, but finally he understood that there was nothing he could do except borrow from people he knew to pay my coyote. Reluctantly, he gave me permission to use his telephone number as my key to crossing the river.

A little consoled, I went to a restaurant for breakfast, since I’d been living for a while on a single meal a day. I also found a public bathhouse. I returned to Nares’ house before noon, and about an hour later we were given a lunch of macaroni, frijoles, and plenty of tortillas. I gave my friend’s telephone number to Nares and waited. It was a monotonous day.

Five of those who had left the night before returned to the house about nine o’clock. They had been caught because one of them, disobeying orders, had stepped out from a hiding place on the north bank of the river.

Later that night it turned cloudy, and a few of us, thinking it might rain, took over two of the cars that were being repaired in the shop across the street. But we went to fill our plates when supper was called, and when we returned to the garage, some other men had taken our places. Since there was no other shelter, a few of us lay down on the concrete driveway and covered ourselves with a blanket we’d found in one of the cars. After a while rain began to fall, slowly at first, then harder. We got up, every man for himself, and looked for new places. I took the bottom of a car seat and pulled it underneath a car with me. The rain splashed at my ribs, but I was able to sleep for a few hours.

At dawn, I counted seventy people in the house of Andrés Nares. Most of those who had left over the past two days were back again, caught by Immigration. A runner had brought in a few more too. A new list of names was called, this time of people bound for Houston. My name was on the list. An hour or two later, we were loaded into the cars. The blue car left first, then the station wagon, in which I rode. After half an hour, the cars stopped in front of a hut, and we were ordered to go inside quickly. We were near the edge of the river.

The shack was an old place with a dirt floor. It was divided into four rooms. The walls of two rooms were made partly of glass, but the panes had fallen out of the frames. The doors were off their hinges, and one window had never been framed. The roof was made of asphalt siding. There was a metal bed in each of the two better rooms, but even those were extremely rusty; their mattresses were stained and filthy, the coverings torn and the stuffing falling out.

In one room an altar sat atop two cardboard boxes. It was covered with a flowered sheet of plastic, and at its sides were two big glasses filled with artificial flowers. On its center a candle had burned halfway down, faintly illuminating two pictures of the Virgin in rusty frames made from tin cans. At the foot of the altar, five newborn puppies rolled around on a mat of old clothing. On a plastered part of the concrete wall, a bad artist had painted in sad colors the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

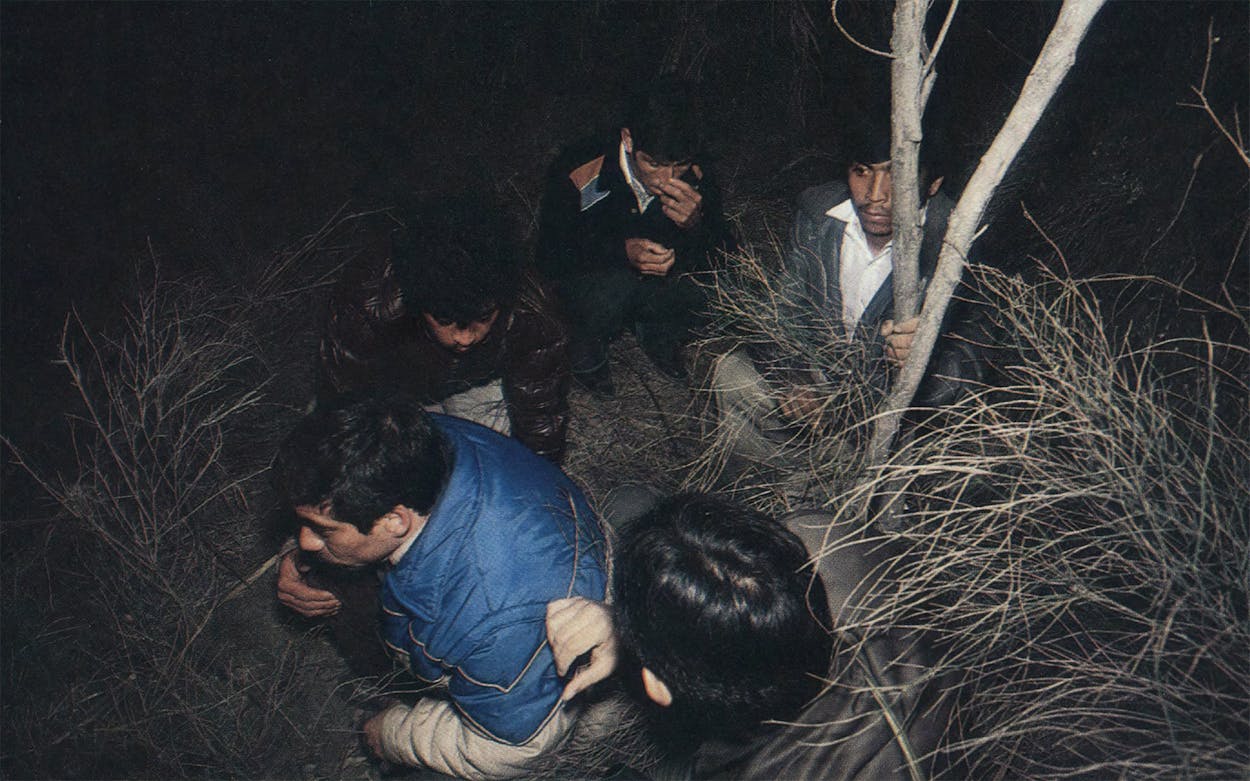

Split up in the four rooms, the 25 of us waited an hour or more before a fat, shirtless man with a tattoo of an Indian maiden on one arm appeared. He told us to look for a signal from the other side of the river. Minutes later a man on the north bank gave a shrill whistle, raised his hand, and extended his fingers. That was the signal that the first five of us should cross.

Ten minutes later he gave the signal again, and my group of five went running toward the river. On our way we passed the fat man, who told us to take off our shoes as soon as we got to the riverbank. “The river has risen!” said one man when we got there. He had waded across two nights before, but that wasn’t possible now. The previous night’s rain had made the river swift, and the rushing water at places produced a roar like that of a thunderstorm. The water was dirty and thick and as gray as the caliche of the riverbanks. Bits of wood and debris floated downstream.

Another man, part of the coyote crew, was stationed at the edge of the river. He told us to get into the life raft he held by a rope. The fat man lowered himself into the water and, swimming with his free hand, pulled the raft into the current. Judging by his motions, I guessed that he could have touched the bottom but couldn’t have stood erect for long in the current. Even with his guidance, the raft drifted downstream.

When we reached the American bank, we put on our shoes and joined the others in the high reeds. A young man with a low voice came and told us to follow him and to walk bent over. For fifteen minutes we followed him up and down little hills, and from time to time he told us to wait while he scouted ahead. We walked and sometimes ran, until we came to a place where houses began cropping out. There another man was waiting for us. “Three at a time now. Run straight ahead. There’s somebody up there who’ll tell you what to do next,” he said. About a hundred yards farther into the United States, another man appeared and pointed us toward the back door of a house.

North of the River

The house, which was made of wood and had peeling paint, occupied about half the lot on which it sat. A patch of the ground was covered by grass and poorly kept flowering plants; the rest was a paved driveway and parking area. We were herded into two big, neat rooms and told to keep quiet until the others came. By late afternoon, all 25 of us had arrived, and we had looked over our new quarters. Conditions were already better here, on the American side: we had a roof over our heads, a private bathroom, and a kitchen equipped with a stove, a sink, and a refrigerator.

The owner of the house was a young man known as Chuco.* He had an athletic build and was dressed in khaki pants, a checkered shirt, and patent leather shoes, in the style of the pachucos of my dad’s youth or the lowrider crowd of today. Chuco ran a well-tuned, precise operation, with drivers, scouts, and other auxiliary personnel. From what the more experienced wetbacks told me, the outfit’s professionalism was the product of an evolution—Chuco had inherited the operation from his father, who had begun more than twenty years before. Chuco would get a third of the $450 that we would pay for the trip, Nares would take a third, and the final third, my companions said, would go to the police in Mexico.

Drivers of different cars came to Chuco’s house and waited for a telephone call in his living room. If the caller said the roads were clear, Chuco would load his goats and the drivers would leave. Shortly after dawn on Monday, two carloads were dispatched that way. Minutes later Chuco came into the room where the rest of us were waiting.

“Just look at you guys taking it easy!” he joked. “So what if you got left behind this morning? You’ll leave in a little while, don’t worry. You shouldn’t eat or drink water, eh? Because once we leave for Houston, we’re not stopping until we get there.” Then he pointed to me. “You,” he said. “We’ve got a phone call to make.”

Apparently Nares hadn’t checked the number I’d given him. I went with Chuco into the living room, where he dialed the number. When my friend answered, he handed the telephone to me. I told my friend that I was north of the river and that Chuco wanted to be sure he would pay for me. My buddy assured Chuco and asked him when we would arrive. Chuco said, “Dios sabrá” (“Only God knows”).

Left behind with me was a middle-aged farm worker named Juan, who was short in stature and seemed to be partly of black ancestry. He threw himself upon the bed, tired and depressed. He had talked about his family and his dream of building a house for them someday. Pedro, an Indian bricklayer from Morelos, occupied the other bed reserved for us. Antonio, a young farmhand, sat down on a couch and began paging through a cowboy comic book. Francisco, a merchant who said he had come to the U.S. with the idea of expanding his capital, decided to take a bath. I took the opportunity to wash my shirt, which was dirty with sweat and soil.

During the five days we waited at Chuco’s house, 23 more people showed up. Five were from El Salvador—one housewife, one female worker, two farmhands, and a university student. There was a couple with aristocratic bearing from Argentina. Among the sixteen Mexicans was a preacher, about thirty years old, with kind eyes and a serene composure. He was tolerant and attentive to every word spoken to him. All of us stayed inside the house because Border Patrol vans passed every afternoon and night. Sometimes agents parked their vans on our street and got out, carrying shotguns, to make sweeps of the river.

The preacher told me that he was a welder by trade but, unfortunately, a welder without tools. He wanted to go to the U.S. to buy more equipment for the little shop he’d started in his village. He had hand tools but no power tools, and although he had already bought an electric welding set, he still needed an acetylene rig. His earlier trips had not enabled him to buy everything at once, and the last trip had been cut short by a family emergency in Mexico.

On the fourth day our spirits darkened when Chuco told us that the body of a drowned man had been found in the river. The dead man, whose identity was unknown, was clad only in his shorts. The preacher began to pray for the poor fellow’s soul. “A wetback like us,” he said. “Only God can know where he came from and who he left waiting for him. Father, we pray and give thanks in Your name, because this man could have been any one of us.”

The next afternoon we left. First, the three shortest among us—the preacher, Juan, and me—were loaded into the trunk of a big car. The rear speakers of the car’s sound system had been removed so that those who rode in the trunk could breathe. I was up against the back seat and could see the sky through the openings. From a reflection in the rear window, I could also make out the inside of the vehicle. Juan lay along the other end of the trunk, and the preacher was in between us. Six others and the driver got into the car, and we took off. From inside the trunk, we felt the car turn several corners and then gain speed, as if it had entered a freeway. “I sure hope we make it,” Juan said.

“May it be God’s will,” the preacher intoned.

After about thirty minutes, the temperature began rising inside the trunk. A morbid thought came to my mind: if we had a wreck, how long might we stay in the trunk and who would let us out? I recalled stories I’d heard about wetbacks smothering or burning to death in trucks and in the trunks of cars. I looked over at the preacher to see if he was worried too. His eyes were closed, and his lips were moving as if he was praying.

We felt the car move onto another paved road, then onto a dirt one. During a period of about two hours, we made several turns, and in the window-glass reflection I saw the driver wave, as if to a lookout, before making some of the turns. Finally the car stopped. We heard a door open, and someone said, “Run.” Then we heard a car pull up alongside ours.

“Pendejo, why are you running?” we heard somebody holler in badly pronounced Spanish. Then we heard slow, heavy footsteps come around the car. The trunk lid flew open, and we saw a big Anglo with blond hair. He was wearing a green uniform and was smoking a pipe.

“How comfortable you look,” he said, as though he was amused. “Get out.”

We found we were on a road in the middle of a treeless plain. There was nothing near us, as far as I could see, but clusters of brush and lines of barbed-wire fence.

“Which one of you is the driver?” the border patrolman asked the three of us.

“None,” we replied in unison, not as amused as he.

The patrolman told us to sit down on the rear of the car. The rest of the passengers were lined up on one of its sides, their grimaces showing their grief over what had happened. I noticed that the driver was gone. The patrolman asked where we had been headed and how much we had paid. We told him that we were going to Houston and that we hadn’t paid anything yet.

“Why did you decide to come today?” he asked, joking again. “Why didn’t you wait until tomorrow? That’s my day off.”

“Let us go,” Juan pleaded.

“No, that’s not possible,” the patrolman said. “You’ll have to go back to Mexico and find yourself a smarter coyote.”

A few minutes later a paddy wagon drove up, along with another Border Patrol car. The agent who had stopped us pointed out the direction in which the driver had taken flight and then spoke to someone on his walkie-talkie. He told us to climb into the paddy wagon, in which eight others were already riding.

In about half an hour, we arrived at the Immigration offices in Hebbronville. Nine of us were locked inside a cell in one of the buildings. There were about ten agents, mostly Mexican Americans, who came in and out of the building. After a while one of the brown-skinned agents approached our cell. He recited the following in Spanish, apparently from memory: “You have been detained for having tried to enter the country illegally. I am going to interrogate you, but first you must know your rights. You do not have to answer questions, and you can request the presence of a lawyer. If you don’t have a lawyer, we will provide you one.” None of us indicated any need for a lawyer.

They let us out of our cell, one by one, to make our statements. “How many times have you been detained by Immigration?” they asked. “Have you ever been arrested by the police? Where were you born? When? What are your parents’ names? Where are you from?” They also wrote down physical descriptions of us. When the questioning was done, they made us sign papers that said we were leaving the country voluntarily after having been detained for violating immigration laws.

As I was walking back to the cell, I noticed that they had brought in our driver. He looked tired, and the fear on his face—that of a condemned man—was so extreme I felt sorry for him. On seeing me, he looked around to make sure that no one was watching and then calmly raised his index finger to his lips. I shook my head as if to say, “They didn’t even ask about you.” He seemed to understand, because the change in his expression was so great, so joyous, that it reminded me of the faces of pantomimists.

After everyone had been questioned, they called our names from a list, and as we went outside to the paddy wagon, we were handed copies of the papers we’d signed. “Is this our passport?” Juan asked the agent who had caught us.

“Yeah, a passport to your country,” the patrolman joked.

In less than half an hour, we were unloaded at the old International Bridge in Laredo. We paid 10 cents each and walked across the bridge in silence. I hadn’t made up my mind whether to try again or not. It seemed to me that it had been a lot of trouble, for nearly all of two weeks, and I didn’t expect any new attempt to go much easier. I was thinking about returning home. “Juan, what are you going to do?” I asked the older man, who by now was almost a father to me.

He turned a little and looked at me hard, incredulity in his eyes. “What else is there to do,” he said, “but try again?”

*Names marked with asterisks have been changed.

Tianguis Pérez is a Mexican national who currently lives in Texas.

This is the first of a two-part series. The author does eventually make it to Houston; part two, “Give Me a Job,” covers his life as an undocumented worker.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Laredo