This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

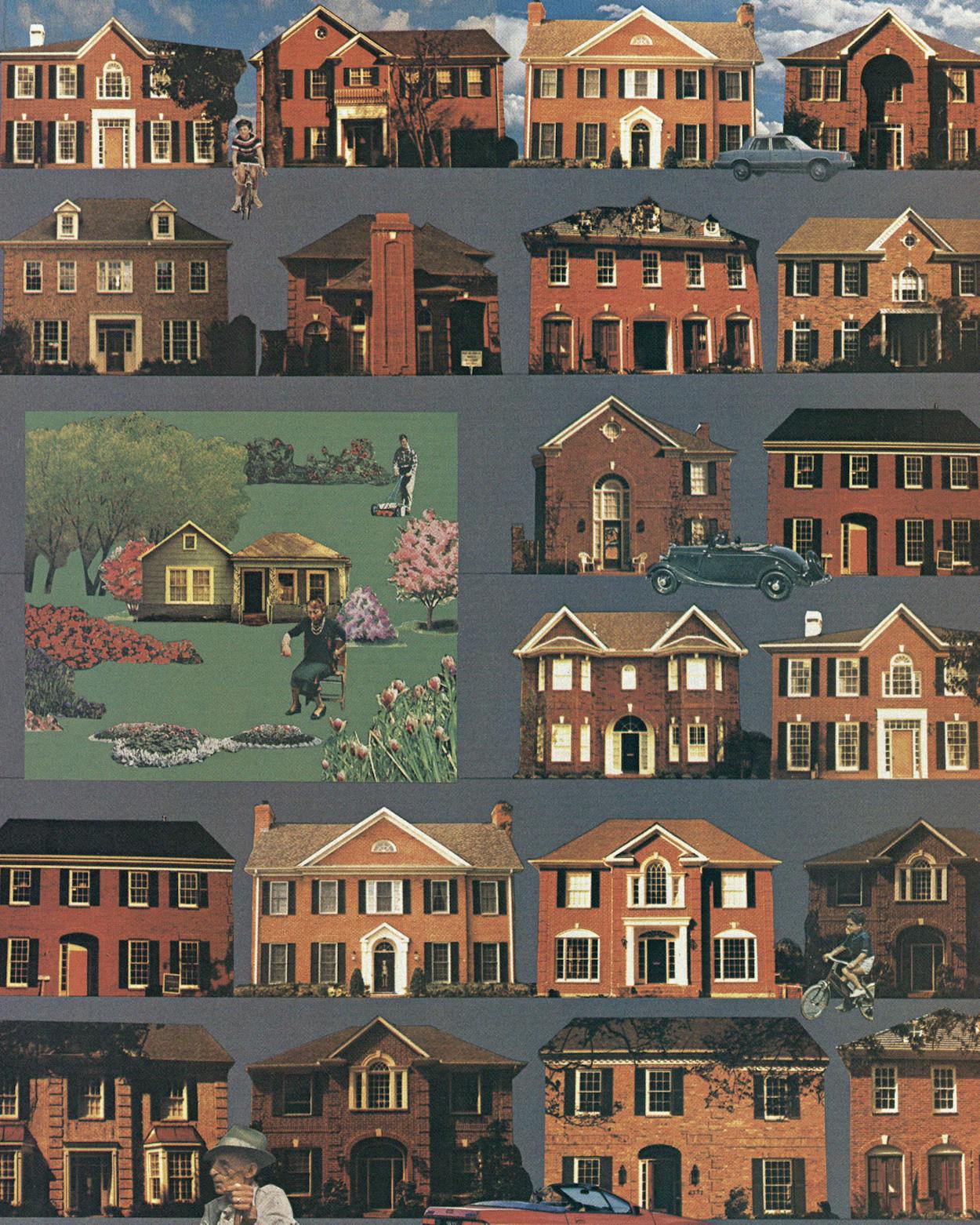

“It’s like buying the potato and getting the steak for free,” says builder Dan Parker, searching for a way to explain the first bona fide real estate boom to strike post-bust Houston. We are touring West University Place, a neighborhood west of Rice University, where the value of any lot (a.k.a. the steak) has come to exceed the value of any house (the potato) that sits upon it. The economics are simple: Combine a lack of empty space with a demand by wealthy homebuyers to get into select inner-loop neighborhoods; add some hungry builders who spent at least three years starved out by the bust, and you have, on block after block, the teardown mania that is transforming West U and other venerable Houston neighborhoods. Where are the two-bedroom, one-bath, thirty- to forty-year-old brick and frame bungalows that eager yuppies once cheerfully scooped up for $135,000? They are going, going, gone—bulldozed in a builders’ frenzy to make way for the yupwardlv mobile homes of the nineties, $400,000 red-brick neo-Georgian mansionettes. “These prices were unheard of two years ago,” Parker confides, steering his Plymouth Voyager down street after converted street. It’s a little unnerving, even for the typical progress-at-any-cost Houstonian: In the last year and a half, plush, inner-loop neighborhoods from West U to River Oaks—and close-in but still plush outer-loop neighborhoods like Memorial—have been metamorphosing into the kind of pricey new subdivisions once found in the county’s most pastoral outskirts. Apparently, the typical post-bust homebuyers—doctors and lawyers, according to Parker; not too many S&L executives—want a kind of Williamsburg West inside the loop, which builders have been only too happy to provide. For around half a million, you too can own a modern version of an eighteenth-century English manor house, complete with gaslights and double dishwashers. “People don’t want the old, they want the new,” says Parker. Not everyone is thrilled about this change, however. As long-time West U resident April Rapier complains, “Welcome to West U, the Sugar Land of Houston.”

Though there are builders who claim they’ve never torn down anything that didn’t deserve it, any house can become a teardown. Sure, a sagging, mildewed, asbestos-sided hovel is marked for death—at $200,000 because it’s on a nifty pine-shaded lot. But a historic River Oaks home (a bargain at $600,000) can meet the same fate just because it’s too cramped or has the pool in the wrong place. Most Houstonians remember the time back in 1985 when Carolyn Farb and other River Oaks picketers could not stop one of Kenneth Schnitzer’s sons from purchasing and then demolishing a lovely John Staub home. But since then—as is so often the case in Houston—the demand for space and the opportunity for hefty profits have overwhelmed the preservationist impulse. Prices of homes in West U, River Oaks, and many neighborhoods in between have gone up 25 to 35 percent in the last year, mainly because people want the lots underneath them. (West U, actually an independent town, is one of Harris County’s five most popular areas for new construction.) Blue-chip realtors who didn’t know the difference between a two-by-four and a table saw have recently opened new construction departments just to arrange the sales of teardowns and the building of brand-new homes. (“It’s a nice house,” said one about a new $475,000 listing, “but it’s a great teardown.”) The teardown has become the latest status symbol: Builders love to cite the River Oaks couple who bought the $600,000 home behind their elegant mansion on Ella Lee Lane—and then tore it down because they wanted a bigger back yard.

The reasons for this latest craze are fairly logical. During the bust, home prices in exclusive neighborhoods became affordable again; subsequently, those prices increased as more and more wealthy couples took advantage of the bargains. These people don’t want just any house, though. Busy, socially ambitious folk need an impressive place, but they do not have the time or the inclination to remodel; they may want to fill their homes with old fixtures and antiques, but they do not want to mess with ancient wiring and plumbing. Enter the builders, who assert that it is much cheaper to knock down an old house and build from scratch than to remodel it according to the requirements of the wealthy. (A foundation for a one-story house, for example, would require very expensive adjustments to accommodate that all-important second story.) As Parker notes, times change, people change: Where people once aspired to own older homes in older neighborhoods, they now want new homes in older neighborhoods. “Couples can move in and go to work the next day,” says Kathy Wetmore, of John Daugherty Realtors.

Still, reducing so many perfectly decent homes to rubble has given even some demolition experts pause (“I’m going to squash one this morning,” mourns Leonard Cherry, who owns a demolition and house-moving company.) Then, too, rising prices have pushed middle-class buyers—who cannot spend more than $150,000 for a house they actually intend to live in—out of the market. Competition for lots has limited purchasers to a handful of crafty, speculative builders. “It’s like trying to get an apartment in New York,” complained one architect. “The builders have all the good lots.” Then there is that lamentable sameness, as the two-story red-brick box smoothes the genial variations of a neighborhood that was at least fifty years in the making. “Though the people who have bought the houses are wonderful people,” says April Rapier, “the houses are relentlessly ugly, relentlessly boring.” But, as with any boom, profits, not aesthetics, feed the frenzy. (Dallas, following trends in Los Angeles, has been similarly afflicted, though to a lesser extent than Houston.) As rising prices are beginning to push some builders out of the inner loop’s best neighborhoods, the bulldozers are rolling into Bellaire, where crackerboxes are starting to list for $150,000. “I don’t know where the end is,” says Parker, lustily eyeing a bungalow that is not, as yet, for sale. “That owner doesn’t have to do anything but sit there and let the economy come to him.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Houston