This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

To Southbound travelers on Interstate 35, Williamson County is indistinguishable from Austin. The unmistakable accoutrements of suburbia—golf course subdivisions, chain motels, McDonald’s arches, and sprawling shopping centers—appear around Georgetown and continue almost unbroken for thirty miles into the urban center. But for many residents of Williamson County, nothing is more basic to their lives than their distance from Austin, not just in miles but in values. In Houston and Dallas, Austin is still regarded wistfully as a Hill Country paradise, but in the exploding suburbs of Williamson County, Austin stands for poor schools, violent crime, high taxes, and most of all, a social permissiveness toward unorthodox lifestyles, evidenced by aging hippies, street people, and a large and vocal homosexual community.

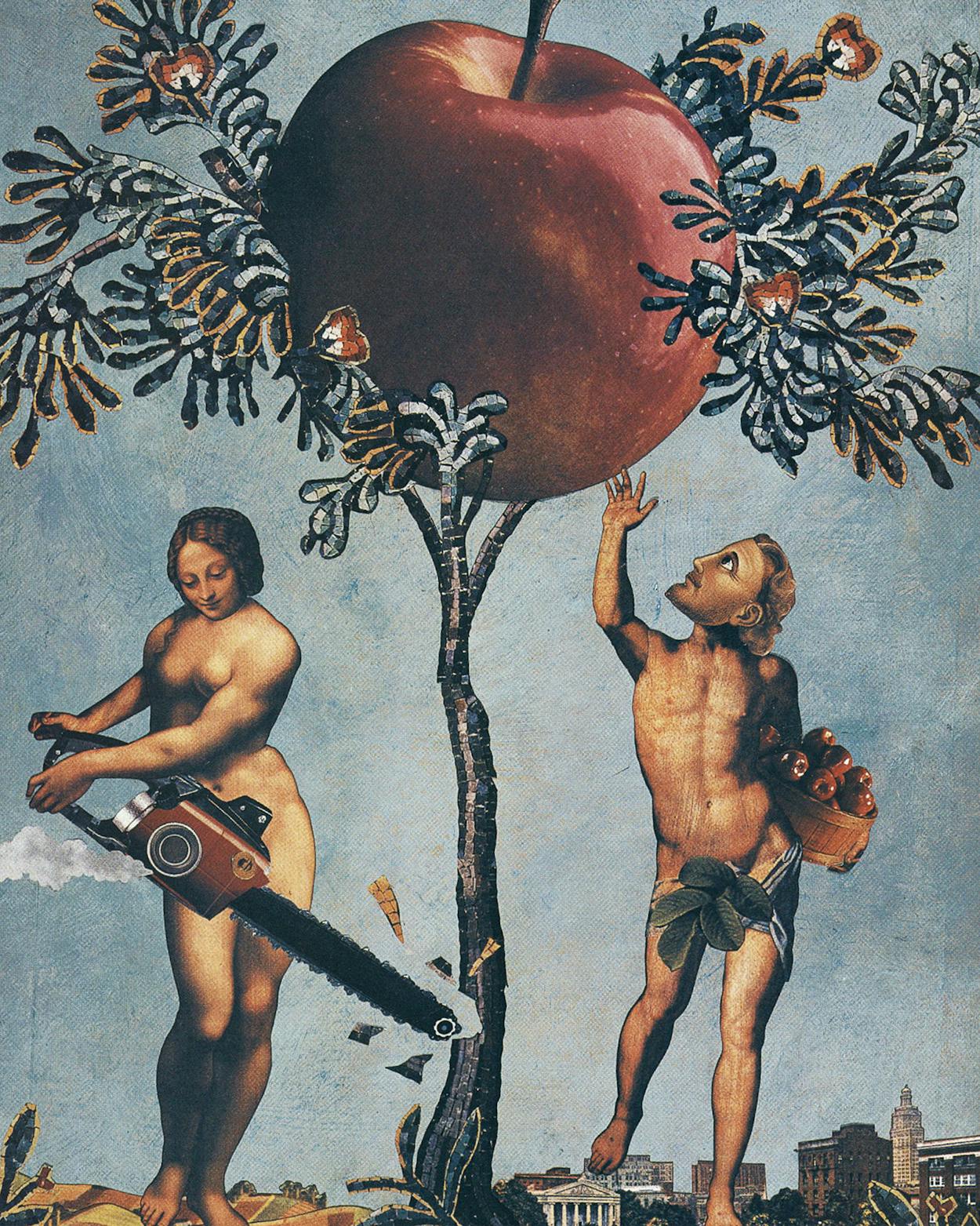

This smoldering hostility toward Austin helped ignite a political fire storm on November 30, when the Williamson County Commissioners’ Court voted by a 3–2 margin to deny a tax break for an $80 million telemarketing center proposed by Apple Computer. The objection was not to the project but to Apple’s corporate policy of extending benefits to live-in partners of homosexual workers. The snub of Apple and its seven hundred jobs was a nationwide media sensation; the New York Times put it on the front page. For a week, until Commissioner David Hays changed his vote, the decision imperiled not just the Apple venture but the economic development efforts of the entire state.

Nowhere, however, was the news from Williamson County greeted with more astonishment than in the rest of Texas. This is, after all, a state that is only now emerging from a decade-long recession and an even longer struggle to diversify its economy. The idea that government should maintain a good business climate has been a mainstay of Texas politics since the end of World War II. Other Texas communities—even Waco, the Baptist heartland—quickly let Apple know that the company was welcome in their towns, if not in Williamson County.

Now Apple’s office project is back on course—but Texas politics is not. The fight over Apple revealed a state that is changing from one dominated by cities to one dominated by suburbs, and a politics that is responding less to economic issues than to questions of values and quality of life. Welcome to post-industrial Texas. Welcome to Williamson County.

Austin is trying to keep business out to protect cave bugs,” said the Reverend Donald Ledbetter. “They’re considered enlightened. Williamson County is trying to keep business out to protect our families. We’re considered Neanderthals.” The Reverend Ledbetter is the pastor of the Heritage Baptist Church in Georgetown. He has the round, expressive face that seems to be a prerequisite for getting into seminary, etched with deep lines that can instantly produce the appropriate emotion. His church occupies a two-story white frame house on a corner one block from the county courthouse where the Apple vote took place. In the foyer is a poster that displays a pile of coins and the words “He is poor indeed whose only goal is making money.”

Churches like Heritage Baptist were leaders in the fight against Apple. Donald Ledbetter wrote a letter to the Williamson County Sun opposing the tax break and urged his congregation to do likewise. “I’m a Baptist, and I believe in the separation of church and state,” he said, looking back on the episode. “But the state doesn’t believe in it. It makes laws that we consider immoral and then says that the church needs to stay out of it. We can’t. When family values are left out, when a community invites bad morals in—and I’m not just talking about homosexuals—you just rip the spirit out of the fabric of the community.”

This is, of course, the language of the Christian right—a term that the Reverend Ledbetter does not like. “I’m considered part of the Christian right,” he said. “I don’t agree with that. I see values as a pendulum that swings left and right. The community changes. The church is supposed to stay in the same place. I deal with people who buy two or three acres and a horse and think, ‘This is the answer to life.’ Of course, it’s not. Character is what brings happiness. Strong fathers make strong families. Strong families make strong churches. Strong churches make a strong community, and a strong community makes a strong government. That’s what we want to get across to our leaders. We felt that voting for Apple was sending the wrong message—that character is not important.”

In the suburbs, small churches like Heritage Baptist attract young newcomers. And Williamson County is teeming with young newcomers. Between 1970 and 1980, its population doubled and since then has almost doubled again, to 140,000. Before white flight from Austin began, the largest and most important town in the county was Taylor, a farming and railroad center seventeen miles east of I-35. Georgetown, the county seat, was a quiet town of 6,000, and Round Rock, just up the road from Austin, was little more than a village. Today Round Rock has more than 30,000 people, and Georgetown is at 15,000, with thousands more living in unincorporated subdivisions just outside the city limits. Taylor, off the commuting route into Austin, has been left behind.

The velocity of change has produced division and resentment. The east side of the county resents its loss of power to the west; the issue of Apple’s tax break was first raised by the county commissioner from Taylor, which stood to gain nothing from new jobs on the west side of the county. Old families resent their loss of power to new arrivals; the First Baptist Church in Georgetown split when younger members wanted to build a gym and took the name of the church to a new building at a roomier location. There is little loyalty to place; in Round Rock, almost everybody works in Austin. On a warm weekday afternoon, I drove through Serenada, a subdivision with ordinary-sized houses on huge lots west of Georgetown, and saw virtually no children at play, just empty yards and empty garages. Arguments for economic development have little resonance for many of the newcomers. To commuters, growth means more cars on the freeway; to small-business owners, growth means competition from Wal-Mart and other giant stores.

It is not surprising that Williamson County is fertile ground for family values and churches, because for many newcomers, the family and the church are the only two institutions in which they are personally involved. Even the public schools no longer command widespread respect. Round Rock is currently involved in an imbroglio over whether the Christian right is behind the recent firing of the school superintendent. Nor is it surprising that homosexuality was the issue that finally brought all of the resentments into the open. Even crime and taxes are not as threatening to the family; homosexuality means the extinguishing of one’s lineage. And to make matters worse, guess which city council last September became the first in Texas to provide domestic-partner benefits to homosexual employees? Austin’s, naturally.

Until the moment came for him to cast the decisive vote, Commissioner David Hays of Georgetown didn’t know what he was going to do. A 34-year-old former college tennis player whose family owns a title insurance company in Georgetown, he was on record as favoring the tax break for Apple. In a letter to the Round Rock Leader, Hays had written, “Government should not tell private industries how to run their businesses! We should do everything we can, however, to lower taxes and ease the financial burden that straps many families today. . . . We need to attract industry into the County to defray the tax burden on our citizens.” But the calls! The phone had been ringing off the wall. Most of the callers said the same thing: “We don’t think our tax dollars should go to support homosexuals.” But that wasn’t really the point anymore. Somehow, the issue had escalated so that a vote for Apple was a vote for homosexuality.

Hays found himself forced to choose between economic development and family values, two principles that he had always supposed went hand in hand. His family had moved to Williamson County when he was nine, and to him it is a place that is tough on crime, welcomes businesses with open arms, and is a great place to raise a family. The furor was a mystery to him; by Williamson County standards, he was an old-timer. He even liked Austin. Hays was an old-fashioned pro-business Republican in a cauldron of political change. If culture and lifestyle were the issues, Hays decided, then he had to vote no.

“I did what I thought I had to do,” Hays reflected later. “I just felt that we needed to step back and let things cool off.” After the Tuesday vote, two other commissioners began working out a new deal: Apple would get its tax break, and developers would donate the right-of-way for new roads, saving the county from having to buy it. The savings would more than offset the lost taxes. But would Apple accept the plan? By now Apple had scores of offers. Hays fretted all Thursday night. An idea came to him: Governor Richards had offered to intervene; he would call her at dawn. They set up a meeting, and on Friday morning three worried men from Williamson County headed for Austin. Richards walked into the meeting room at the Four Seasons Hotel, saw some dirty coffee cups on a table, and busily started cleaning. For the first time in days, Hays relaxed. “I felt like I was visiting my mother,” he recalled. He explained the deal. “You boys go downstairs and get something to eat,” Richards said. She called Apple, and thirty minutes later the deal was done. On December 7, the commissioners’ court made it official. The vote was expected to be unanimous, but to Hays’s dismay, the other opponents of the tax break repeated their negative votes.

Although the final arrangement was a better deal for Williamson County than the original, Hays received 139 calls against his second vote, only 22 in support. He had violated an old rule of politics: Take a stand and make one side mad; change a stand and make both sides mad. “It’s probably the worst thing I could have done politically,” Hays acknowledged of his encounter with the new politics of suburbia, “but I’m a better person because of it. I don’t agree with the lifestyle, but you don’t have to support it or condone it to be concerned about AIDS or care about people.

“It would have been almost bigoted not to vote the way I did the second time.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Georgetown