When I was eighteen years old I packed up my car and left Texas forever. Or maybe not forever, but I’m still gone. I go home for visits, but since that bright sunny day in 1985, when I drove off to college in Tennessee, I haven’t lived in my home state for longer than a week or two, though I think about it all the time. The Texas that I keep in mind is a particular landscape, the landscape of the borderlands stretching west from Del Rio through Comstock out toward the Trans-Pecos creosote flats along the Rio Grande—but also and especially the canyonlands just to the north that drain into the Devils River as it winds its way toward Lake Amistad. Above all, I think of Juno (a spot in the road, no longer a town), the post office and the school, the hotels and saloons and the old country store long gone, the stones and the lovely old hardwood carried off, “reclaimed,” or gone to dust.

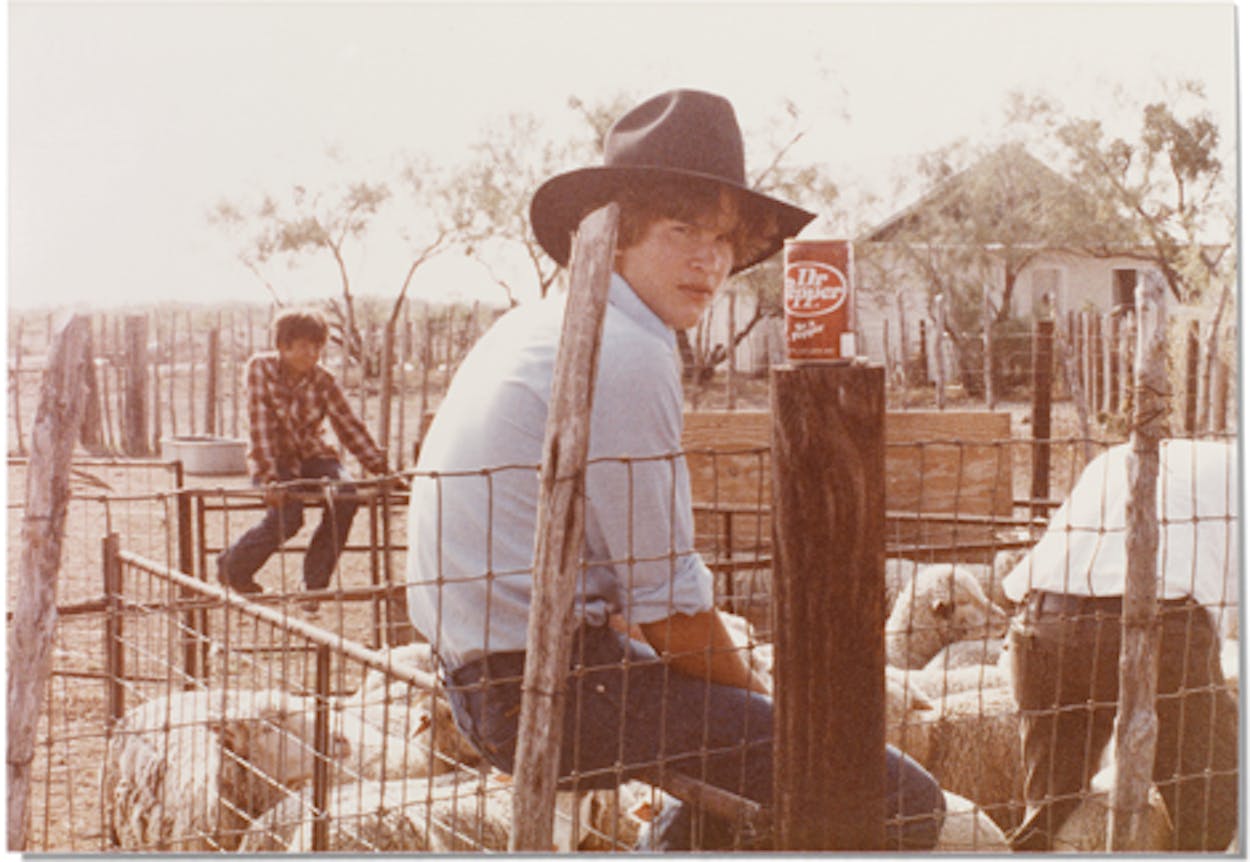

My great-grandfather, whom we called Dandy but whose given name was Earl Wilson, was just a young boy when his father brought the family to Juno. When I was a boy, spending my summers working sheep and goats and cattle on the family ranch, the house Dandy grew up in was still standing, miles from the main road, near a set of pens and a shearing barn called the Murrah Place. As I recall, it was in that barn that I sheared my first sheep, a difficult job that I mostly avoided thereafter. Near that ruined house I shot my first deer and changed my first flat tire. I tried to imagine what it would have been like to live out there, in that high lonesome country, traveling by horseback every morning to a remote schoolhouse where a teacher, in awesome solitude, taught the children of a handful of ranching families.

My ancestral home, as I think of it, is the Beaver Lake Ranch, where the Devils River flows somewhere down below the surface of the bone-white gravel. Ancient live oak trees shade the banks. Stagnant ponds covered in green scum, the remnants of flash floods that can fill the mile-wide valley, dot the old lake bed, and the gnawed leavings of a recently departed beaver colony lie scattered over the dried mud. I see it in my mind’s eye. Up the road a few miles where the store used to be, and not far from where my cousin lies buried, the beavers are still busy, taking down cottonwood trees and stripping them of bark.

I never expected to be a professional Texan, one of those writers who wears the lone star like a brand, who plays up the drawl and affects pointy boots or a cowboy hat with a tailored suit. Even as a boy I never had much of an accent, and people still express shock when I tell them where I’m from, for Texas to New Yorkers and other lifelong city dwellers is a magical place, full of the mystery that attends sites of epic violence and heroic struggle. Then, several years ago, when largely by accident I came to occupy the editor’s chair of Harper’s Magazine, I was interviewed by a colorful media reporter for the New York Times. When he discovered I was from Texas, he asked me whether I owned a gun. I told him I did, whereupon he asked if I was a good shot. Once more I answered, with some hemming and hawing about being out of practice, in the affirmative. And so was born the public image of the cowboy editor with a “gimlet eye,” a cartoon character that quickly made its way, much to my wife’s amusement, to the online gossip sites.

I was surprised by the discovery that I was a “Texan,” yet I had to accept the judgment. As it happened I was just then writing an essay on Cormac McCarthy and the puzzling reception of No Country for Old Men, his great novel of the low-intensity warfare that has been consuming the borderlands for a generation. McCarthy’s fiction had long been the primary medium through which I indulged a stubborn nostalgia for my lost Texas landscape. No other writer has so perfectly captured the sublimity of that harsh country, its deceptive subtle beauty and unforgiving power. Mc-Carthy’s miraculous prose comforted me in my spiritual exile and helped make bearable the collapsed horizons of life in a co-op apartment above a troll-like neighbor who regularly protested my toddler’s heavy footsteps with broomstick blows to her ceiling.

This past February, free at last of both the troll and the responsibilities of running a national magazine, ensconced in a modest homestead in Flatbush, Brooklyn, my thoughts quickly turned to my lost landscape. My children required instruction in handling a rifle, and it had been too long since my soul was refreshed by the sight of a limestone countryside dotted with mesquite and prickly pear.

We met my family in Juno; my father taught my boys to shoot, and my grandmother told us stories of the town’s heyday, of saloons and stagecoaches, Indians and outlaws. On the hill above the rock house my grandfather built from native stone, we found ancient Indian metates, grinding holes in the caprock overlooking the valley, where meal was made, perhaps from the acorns of those gnarled oak trees along the riverbank, over the course of hundreds if not thousands of years. Right next to it was a mysterious concrete receptacle, about four feet high, clearly unused for decades. My father told me, as we watched my boys searching for arrowheads near an old midden that had been broken open by a bulldozer fighting a brush fire, that the tank had been used to fight screwworms in the thirties. When I was a boy, rambouillet sheep and Angora goats populated the pastures of that ranch. Today they are all gone, replaced by Spanish goats, which are exported to places like Detroit and Brooklyn, to be eaten. The neighboring ranches are mostly empty of livestock now, predator populations are booming, and exotic creatures like aoudads and feral hogs have begun to invade. Like all American landscapes, that of West Texas is a palimpsest of lost and vanishing lifeways. Yet the aura of a potent mythology lies heavily upon the land and exerts a fascination that defies analysis; it draws new blood, new life, to refresh the thorny countryside.

My youngest son tells me that when he grows up, he’s moving to Texas.