This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was dark and cold, and the November air was damp. A very large, very white full moon hung close and low over the horizon, looking as if it were about to settle on the roof of the Ashford Village shopping center in far West Houston. The main parking lot in front of the center was deserted, but in the lot on the side of the long rectangular building were several cars, their motors running and the heat turned up inside. Beads of mist glistened in the beams of the headlights. It was 5:45 a.m., and everyone was waiting for one door to open—the door to Here We Grow Day Care Center.

One fluorescent light inside cast an eerie glow through the giant, brightly painted cartoon figures that covered the center’s plate-glass front. At 6, a maroon station wagon pulled briskly up to the sidewalk. All four doors popped open. As a tall, handsomely dressed woman got out of the station wagon, walked up to the front door, and unlocked it, life burst from the other cars. Parents disengaged babies from car harnesses, coaxed children out of back seats, collected bags and bottles, and filed into the center.

Official opening time at Here We Grow is 6:15. By 6:20, Mrs. Isabelle Royer, the owner, had eleven charges on her hands. She greeted them with warm smiles, hugs, and kisses. She looked over each child to make sure no one was sick enough to be home in bed; hung up little jackets; asked one of her assistants (who lived in her house and thus had arrived with her) to prepare a cold cereal breakfast for the children who said they hadn’t yet eaten; switched on the TV and found cartoons; helped parents locate a cubbyhole to store bottles, diapers, and a change of clothing; labeled every medicine that was given her and got written directions for its use and a signed release from the parents; collected some money; and got one of the staffers to drive her own daughters, Crystal and Barbie, who had also arrived with her, to grade school. While she did all this, Mrs. Royer kept up a steady stream of sweet words to soothe anxious babies. Her voice was low and calm.

When a few more staff members showed up, Mrs. Royer let them take over and went into her office. The rush of parents was steady for a good hour. A dark-haired woman named Sue Meeker arrived with a twin at each side. The blonde four-year-old girls, Christy and Jenny, were hollow-eyed and resignedly fretful about being up so early, but they soon settled down to chatting with a girlfriend. Two two-year-old girls lay down on the floor in front of the TV set, and with their jackets curled around them and bottles in their mouths, they sucked and dozed. A couple of fathers came in carrying two-month-old infants in their arms; they headed for the nursery at the back of the center.

Jennifer Schanhals, a blonde, blue-eyed fifteen-month-old who looks like the original Gerber baby, was put in a playpen by her mother; she dropped off to sleep immediately. One two-year-old collapsed in a heap and began to howl as soon as her mother got her in the door. “She always cries when we get here,” said the mother to no one in particular. “It makes me feel so bad.” The other mothers, prying off their own reluctant children, nodded sympathetically. Everyone was in a rush. There were offices to get to, traffic jams to consider, but most important, teary scenes to avoid. The parents knew that if they lingered, they were asking for trouble.

At 7, two-and-a-half-year-old Kevin Bouquet arrived with his father, who put him down gently, took off his coat, and gave him a big, reassuring hug. The dark-eyed, pale boy looked around, but stayed in his father’s embrace. “Now, Kevin, I hope you’re going to have a nice day,” Eugene Bouquet said quietly. “Do you remember what we learned last night, Kevin? Remember what I taught you? Don’t take any . . .” He trailed off, but his son dutifully picked it up. “Wooden nickels!” he shouted. “No more wooden nickels!” and Kevin ran off to join his friends.

The Bouquets, the Schanhalses, the Meekers, and all the other parents whose children are in the day care center have one thing in common besides living in Houston and choosing Here We Grow as the place that will take care of their children from morning until evening: they all share a dream of the kind of life they want to live. That dream includes doing satisfying work and being able to afford two cars and a house with a yard in a community toward which they might someday feel attached.

The only way for many of these people to realize their ambitions—and, just as important, to get what they want sooner rather than later—is for both parents to work. Texas is fast becoming a suburban state, and competition for houses has driven prices up. It costs a lot to cash in on the American dream these days. Besides the financial reasons to work, there are other strong incentives: power, status, a sense of accomplishment. Our society has less and less regard for someone who stays home to take care of children.

For all these parents, day care is like the keystone in the arch; it is the thing that holds their lives together. If they didn’t have day care, one parent would have to stay home with the children—and most often, tradition being hard to fight, that job would fall to the mother. Without two incomes, most couples wouldn’t be able to afford the house or the neighborhood they live in. Their social status, as well as their economic status, would be much lower. But these people have a choice about the kinds of lives they are leading because they’ve found an affordable solution to one big problem: what to do with the kids all day.

It is not a simple solution, though. Day care centers are not like nursery schools. The goal of a day care center is not to teach but to baby-sit. Children will receive as much, or as little, attention and instruction as it takes to keep them fairly quiet and well behaved for long stretches of time. And no child ever spends as much time in a nursery school as children spend in day care centers. Often, within five weeks of birth babies are put in day care centers for ten or twelve hours a day, five days a week. During that time, the strongest emotional and physical bond there is—that between a mother and her child—is broken. What long-term effect this will have on children, on their parents, and on our society, no one knows. In fact, hardly anyone knows exactly what the hundreds of thousands of children in Texas who spend their days in day care centers actually do there—what activities and feelings texture their hours. Even their parents don’t know.

Day care is by no means an innovative solution for working parents, but it has had a rocky history. The first day care center in this country was probably the Boston Infant School, opened in 1828, which tended children at a weekly charge of 6 cents. Day care became popular in the last decades of the nineteenth century, mostly because of the arrival of huge numbers of immigrants and a shift to urban life and jobs in industry rather than agriculture. Day care nurseries were run by upper-class women as charities; they provided alternatives to the orphanages and county children’s homes to which the children of working mothers had traditionally been sent.

In 1921 Congress passed immigration restrictions, and after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the feminist movement lost momentum, giving way to those who preached that women should stay home. Day care became a minor part of social welfare programs, a service for problem mothers with maladjusted families; because of the stigma attached to it, fewer mothers turned to day care. Through the twenties, welfare was not a fashionable cause, and with the onset of the Depression the centers that were left closed down. In 1933 President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration opened about 1900 day care nurseries, but by the end of the thirties day care was in decline again.

It was revived when so many women took jobs during World War II. The government spent about $50 million to set up 2800 day care centers. After the war, the centers were shut down, in the expectation that women would quit their jobs. But the war left behind many women who were divorced, had been deserted or widowed, had disabled husbands, or simply enjoyed their jobs—they all continued to work. In 1940 one in eight mothers worked. In the fifties, one third of all women were employed outside the home, and that number has climbed steadily. In 1956, 70 per cent of families with incomes in the middle-class range, which was then from $7000 to $15,000, had two wage earners. Finding adequate care for children was an enormous problem for working women; they turned to neighbors and relatives or organized their own centers.

Largely because of the women’s liberation movement, in the sixties people began to accept that women would not—and often could not—stop working. For the first time, day care became a political issue. In 1967 there were 10,400 day care centers in the country; by 1975 there were nearly 29,000.

In Texas there were 567 centers in 1960 and 1803 in 1970; in 1981 there were 4389. In Harris County there are now 838 centers, with a capacity of 63,998 children. Pick up a copy of the Manhattan Yellow Pages, and you’ll find fewer than two columns’ worth of listings under Day Nurseries & Child Care. Look under the same heading in Houston’s Yellow Pages (right after Dating Services and right before Debt adjusters), and you’ll find nearly thirteen pages of listings and advertisements. Day care listings are right up there with those for plumbing, jewelers, insurance, and furniture dealers.

The Houston listings include national franchises (called Kentucky Fried Children by many in the industry) and chains like La Petite Academy (which has 35 Houston-area locations) and National Child Care Centers (30 in Houston); local chains like Toddler House (7 locations) and Mangum Oaks Schools (13 locations); at least a dozen all-night centers like around the Clock Child Care and Texas Tots School; and hundreds of private centers with sentimental names like a Children’s Island, Aladdin’s World, Bunny Land A-Cat-A Me, Camelot, Care-A-Lot, Grandma’s House, Peter Pan Palace, and Unicorn University.

I dropped in unannounced, at all hours of the day and night, on dozens of day care centers in West Houston. In obvious ways, all centers are different, from the buildings they are in, to the activities they offer, to the people who staff them. The age limits they set vary widely, and so do their hours and prices. Some are clearly better than others; some are shockingly bad—they are filthy, the children are unsupervised, hungry, and upset. The Department of Human Resources once discovered a center that was using the children to make pornographic films.

Here We Grow is a good day care center, and that is why it is especially interesting. The cost of sending a child there is between $35 and $60 a week, depending on his age, but most of the customers think the center is worth the price, not only because it is clean and spacious and has a good supply of crayons, paper, glue, and toys but because it is staffed with people who care about children. What Here We Grow does well, it does well because of the talent and dedication of Mrs. Royer. What it does badly, every day care center does badly by its very nature.

The parents whose dreams and ambitions depend on Here We Grow live in the neighborhoods off Westheimer Road, about twenty miles west of downtown Houston. Out here, Westheimer is smooth and wide and streaked with the muddy tire tracks of big trucks, a telltale sign of booming development. Fifteen years ago this part of Westheimer was a two-lane strip of road that cut through miles of pasture. Teenagers used it for parking and drag racing. There are still some pastures today, but they are destined to be covered with new homes. Dozens of carefully designed and painted billboards advertise “Victorian styling” or “contemporary luxury,” automatic garage-door openers and swimming-and-tennis clubs. Fences border much of Westheimer, walling off the thousands of homes that stretch into a horizon unbroken by high rises. As far as the eye can see, the eye sees roofs of houses, frontier Houston’s amber waves of grain.

Mrs. Royer moved into this part of Houston years ago, and in 1971, when she had her second child, she decided to start what is called a day home. She would keep five or six children in her own home while their parents worked. Mrs. Royer, who had been trained as a nurse in Chile, where she grew up, felt she could do a good job with other people’s children and raise her own at the same time. Her husband, Russell, the engineer supervisor at Joske’s Post Oak store, did not mind all the extra children in the least. Mrs. Royer loved her charges, and over the years—through a move to a big, new house off Memorial Drive, with room for more babies, and through the birth of her third child—she dreamed of building up her business.

In January 1981 she signed a lease for 2700 square feet of space in a brand-new shopping center on Dairy-Ashford, the last major road off Westheimer before it gets to the Barker Reservoir. Among Mrs. Royer’s neighbors in the shopping center are Pride Cleaners (the manager of which Mrs. Royer recruited as her personnel supervisor), Ridgway Office Equipment, Bee Jay’s Club (BEER. BUST. STAG LADIES DRINK FREE SUN MON TUES), Benson Pools, Dinette Showcase, Quarterback Sports (featuring row upon row of Browning and Winchester rifles), the Car Store, the Dance Studio (where Mrs. Royer intends to send some of her older charges for lessons), and the Phone Center Store. None of Mrs. Royer’s neighbors mind the day care center. Donnie Rey, whose office at Ridgway Office Equipment abuts Here We Grow, used to complain when Mrs. Royer would come over during his lunch break and ask him to turn his radio down, but he was secretly impressed by her protectiveness—and anyway, his two-month-old son is napping there now. All in all, Mrs. Royer found a good shopping center community.

Here We Grow opened with a license from the Texas Department of Human Resources to enroll up to 70 children, from several weeks to twelve years of age. By July, Mrs. Royer was ready to expand, so, leasing another 3600 square feet of space, she applied for a new license for a capacity of 190 children. She rented a large red portable sign and had it perched on the edge of Dairy-ashford along with seven or eight other signs advertising new businesses, with its big arrow pointing in the general direction of her door. The sign read:

HERE WE GROW

WE’RE

GROWING

OPENING 2ND PART

FOR FALL

SPEC PRICES

The response was overwhelming. By August, she had 35 or 40 names on a waiting list, with more coming in every day. She developed a floor plan, ordered carpeting, installed bathrooms with child-size toilets and sinks and adult-size showers (taking care of children gets messy), and began to wait—a wait that lasted through the fall and early winter months—for the fire, health, building, and day care inspections that would clear the way for the opening.

When Mrs. Royer first moved her business to Ashford Village, some of the parents withdrew their children; the move from a house to a large space in a shopping center was simply too much. But most of them were loyal. As Gene Bouquet says, “Kevin has been with Isabelle since he was eight weeks old. She has given a lot of herself caring for him. We thought we should give her a chance. She is a classic case of someone who has created a good thing and then has to make it bigger—she is in business, after all. The problem is, the nature of the original creation is going to have to change. Isabelle was the center of those children’s lives on a day-to-day level.” And indeed, what inspires everyone’s confidence in Mrs. Royer is her unflagging affection for children.

Many of Mrs. Royer’s customers chose Here We Grow only after spending a great deal of time and energy to find the right day care center. Every evening and every weekend, they watch their children carefully for signs that they have made the right decision. They see that their children are not picking up colds from the others, or that they come home with fistfuls of colorful hat bands and paper collages, or that they have learned a new song, or that their diapers are dry and their clothes clean. It’s harder to gauge moods: they see that in general their children seem well adjusted and carefree, but if they are fretful or anxious at the end of a long day—well, it is late and everyone is hungry.

No matter how much the children show or tell them about day care, though, none of the parents have a clear idea of what their children are doing from the moment they are dropped off until the moment they are picked up. And even though the children will be doing many different kinds of things during all those hours, there is a subtle sameness to life in a day care center. No child can explain to his parents, and no parent can see in a quick visit, that no matter what else is going on, day care children spend a lot of time doing one thing: waiting for Mommy.

Mmmm,” said a woman the first time she arrived with her child at Here We Grow. “Smells like you got babies in here.” The smell of a day care center that keeps infants is irrepressible. It is a smell familiar to any parent, but amplified many times—an acrid mix of food, cleaning fluids, lotions, and, mostly, dirty diapers. Unless someone’s only job is to run back and forth to the garbage dumpsters all day—and there’s no telling if even that would do the trick—nothing can be done about the smell. Because Here We Grow is a clean place, the smell is not as strong as it is in many centers, but still it permeates the hair and clothing and, it seems, even the skin of those who work there. No amount of perfume masks it for long. The smell lingers, an olfactory memory, after the end of the day.

The main source of the smell at Here We Grow is a large trash barrel in the nursery, which is an enclosed, windowless room furnished with eleven cribs, three playpens, and one automatic swing. Toys and mobiles are scattered about. There is a changing area next to a sink, and there are a couple of chairs and a rocker for the two women who supervise the nursery to sit in while they give the babies their bottles. A small portable TV stands near the changing area. It is tuned to the soap operas most of the day, but no one watches seriously. The sound of adult actors and adult problems is simply a counterpoint to baby noises and baby problems.

All day long, eleven to fifteen babies from about eight weeks to twelve months old lie in their cribs or sit in their pens and scream for attention, stare at the ceiling, gurgle quietly, or sleep. Their days are even more uneventful than are most babies’ days at home. They cannot be taken outside, as that would require three times as many staff members for the nursery and a lot of perambulators. The sitters cannot play with any child for very long because, as one of them explained, the child would get used to the attention and scream whenever he didn’t get it. (This woman’s own newborn stays at a neighbor’s house all day; Mrs. Royer does not allow workers to bring children to the center on the grounds that their presence would distract their mothers.)

The babies seem unaware of each other, but they are extraordinarily attentive to the presence of large-sized people in the nursery. They follow every movement of an adult and will flirt—or holler—shamelessly to get one to stop and stand next to their cribs. Only one boy consistently wanted to be left alone as much as possible. He seemed truly unhappy, in the sullen way children have of showing depression. He held the railing of his crib and rocked back and forth, back and forth, all day. He did not want to be interrupted, did not reach out to be picked up, and screamed with joy only once during the day, when his mother came to get him and ended his ten-hour vigil.

The nursery group is only one of six age groups at the center. The children in the twelve-to-eighteen-month group—Jennifer Schanhals is one of them—live in playpens that are lined up against the wall in two ranks. Theirs is the only enclosed room besides the nursery; the other groups are in two large rooms divided into smaller areas by folding partitions. Jennifer’s group is watched over by two young South American women who do not speak very much English and so cannot teach the children many words.

These babies share everything. Pacifiers, bottles, stuffed animals, and dolls get passed from hand to hand, mouth to mouth. When they are on the floor in the middle of the room playing together, they get noisy and they intimidate some of their roommates. One day a little boy kept leaving the group and wedging himself between the pens, pulling the net mesh across his face. The sitters drew him out and plunked him down with the others several times. Finally he jammed himself under a playpen and hid in that dark, tight space for a while. There is no other place to which a shy child can retreat, no place to go for a little quiet.

The children are attracted to adults like iron filings to a magnet. They are wily—and mobile—enough to demand attention in such a way as to be sure to get it. When they want hugs, they press themselves against adults so that they have to be peeled off. When they want to be lifted, they raise their arms like little suppliants. If they get what they want often enough, they become spoiled, and that, in a day care center, is to be avoided at all costs. Unfortunately, in day care parlance spoiling a child has come to mean giving him what every child needs and wants—not candy or fancy toys or cute clothes but hugs and kisses and soft words. Spoiling a child is a sin and a pain in the neck, for the child who is spoiled cannot be left alone without creating a miserable scene.

How much attention a child can get without becoming spoiled is a big question in day care centers. A good day care worker would never be aloof around children, but she knows that she treads a fine line when she is affectionate with them. Holding a child just a little too often or standing by one crib a little too long creates unfulfillable expectations in one child and unleashes the jealousy and insecurity of the others, who have an inscrutable way of tallying up every kiss doled out and demanding one of their own when the balance is off.

Only as the children get older, from about a year and a half on, do they seem to reconcile themselves to the fact that they are never going to get as much attention as they want from their sitters. Like children anywhere, they are absorbed in their play and in each other. They are beginning to explore their world; their imaginations are reaching out. They are becoming aware of possessions and status.

No one at Here We Grow is allowed to claim any of the center’s toys as his own—not for a day, not for an hour. The rule makes perfectly good sense, as far as keeping things humming along smoothly. As soon as a child becomes engrossed in a toy, his playmates want that toy and start fighting for it. Don’t let toys get special, and everyone stays calm. So it is next to impossible for day care kids to express their growing sense of possessiveness. Perhaps that is good; Gene Bouquet remarked that Kevin always seems to know how to share his things and play with others much better than his friends’ children who don’t go to day care centers. However, because he is not allowed to hang on to an object, a child in a day care center can’t spend hours constructing a make-believe world around his toys. A day care child cannot have a fire truck and pretend he’s a fireman for a while. He can’t claim a doll as his baby and mother it all day. Children have a need for that kind of play. The ones who manage to get around the center’s toy rule by bringing special things with them from home have a high status among their classmates—they’re the cool kids of Here We Grow.

Two-and-a-half-year-old Brian Cope, whose father is a coach at a nearby high school, brings a large football helmet every day. He can’t play with it, though, because as soon as he gets it out the other children want their own football helmets. Mrs. Royer’s rule is that special toys—helmets, ragged blankets, dolls that still have hair—must remain on top of the cubbyholes all day. And there they sit.

The toys are weighted with emotional significance; they are a reminder of home. Whenever Brian Cope notices his football helmet, which is often, he will begin to talk in a tiny, quiet voice about how his daddy is teaching him to tackle, how he goes to all the games, how the players are his friends . . . and soon he is looking pretty glum, like he wouldn’t mind making a dash for home. His sitters can never get him to stop thinking about football, to stop demonstrating his tackles and dives. But Brian’s preoccupation with football isn’t all bad. His football helmet might make him homesick, but it also makes him special—so special, in fact, that everyone at the center calls him Mr. Cope.

Lessons for Mr. Cope and his two-and-a-half-year-old buddies, one of whom is Kevin Bouquet, fit into a general scheme for effective baby-sitting. The lessons are rather loosely planned around reciting the alphabet and counting to ten. One morning their teacher began by drawing letters in Magic Marker on a sheet of paper, earnestly trying to get her class to repeat each letter as she taped the sheet to the wall. She got as far as D before she realized that it wasn’t going to be an easy day. She couldn’t hold the children’s attention, but because they were behaving pretty well, she went ahead by herself, printing letters and putting them on the wall. The children quietly wiggled around on their benches, slipped under the table, and played games with each other. The three- and four-year-olds in the large room next door, where Jenny and Christy Meeker spend the day, can sit still long enough to get good lessons in shapes and colors. They are asked to recognize the look of their written names and are taught long songs. But the teachers don’t have the time—or the energy—to be sure that each child is learning to pronounce words correctly. One parent visits the center every few weeks just to learn the songs that are being taught; her son’s versions are so garbled that she can’t understand him.

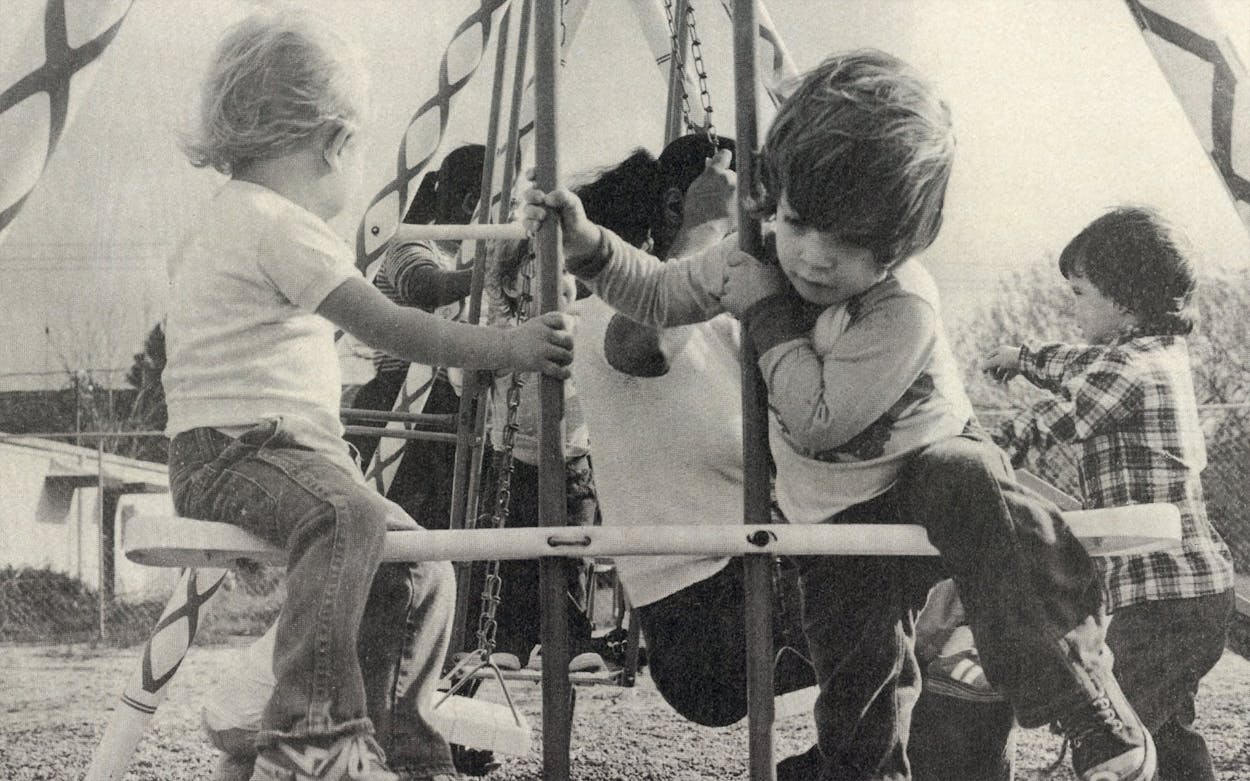

The key to keeping children well behaved, every sitter soon learns, is breaking up the day into short segments of activities; whenever one diversion becomes boring, the sitter has to have another ready. At Here We Grow, as at most day care centers, there is a well-established routine of lesson time and snack time and toilet time and playtime and lunchtime and nap time. Whenever the older children (about two years) go outside to play, they are thrilled at the change of scene. They cannot go out during the hot summer months, and they cannot go out for a few days after a heavy rain because the playground is too soggy, but when conditions are right, they get twenty minutes or so in the mornings and in the afternoons.

The playground is a fenced-off area in a vacant lot at the back of the shopping center. It has a couple of colorfully striped swing sets and sliding boards and lots of room to run around. To get to the playground, the children have a short walk from the front door, past Pride Cleaners, across a driveway (which is used for deliveries and garbage pickup), and through the wire mesh gate. “I feel like I’m going out for exercise at San Quentin every time I walk in this place,” says one of the sitters.

As the three-year-olds scrambled for coats and lined up to go to the playground one morning last fall, the swell of excitement in their chatter was remarkable. Once they were inside the gate, some of them fanned out to the swing sets. The three or four inches of gravel that cover the ground crackled under their feet like static electricity. A few stood perfectly still off to the side, just taking in the light and the cool air and all the activity. But most of them stayed in little clusters near the gate and crouched down to play with the gravel. It fascinated them more than anything else that day.

Using pieces of pipe or old bicycle reflectors that they found among the weeds in the corner of the yard, they scraped down to the damp dirt under the gravel and sifted through the pebbles they overturned, looking for tiny snail shells. This was absorbing work. The children knew enough about the difference between beaches and gravel playgrounds to be intrigued by the mysterious shells; the possibility of uncovering one livened up a day of few surprises. Only one child found a shell during that fifteen-minute dig. She examined it furtively and slipped it into her pocket.

Before long, it was time to line the children up, gather up the stragglers, and go back inside. Lining up seemed to take almost as much time as the children had had for play; well-ordered, obedient two-and-a-half-year-olds are hard to come by.

Discipline vies with spoiling as a subject of discussion among day care workers. Department of Human Resources regulations strictly forbid any worker at a licensed day care center to shake or hit or spank a child, and some of the sitters at Here We Grow seem at a loss for what to do with bullies and brats. It is also against the rules at Here We Grow for staff members to say anything negative about a child to his parents. That rule is common in day care centers, because directors feel that the parents will assume any problem is the fault of the center and withdraw their child.

“Most parents don’t want to discipline their children,” says Mrs. Royer, “and that makes our job much harder. They feel guilty about not having been with their children all day, and the last thing they want to do is make them angry and resentful by scolding them. Parents are always coming to me for advice on handling bad behavior. I tell them, be firm, be calm. Keep a relaxed atmosphere. Otherwise, Dad’s going to come home and find his wife screaming, the kids screaming, and he’ll say, ‘Okay. Enough. My family is falling apart. My wife had better stay home.’ ”

The children at Here We Grow nonetheless have a keenly developed sense of who the authorities are, and they sort them into the two most important categories of people in their lives: mommies and teachers. “Mommy” is what the child will call the sitter who cares for him every day. “You’d be surprised how many of these kids call you Mommy,” says one supervisor. “It was unnerving at first, but now I take it as a compliment.” Teacher gives the lessons; sometimes the person who was Mommy at playtime becomes Teacher during classes. Within ten minutes of my arrival, a four-year-old boy approached me to settle the question of my identity: “Are you a mommy?” he asked. “Are you a teacher? . . . Well, what are you then?”

Whenever an adult enters the center, every child thinks, for a split second, that that person is Mommy. Each child wants to see Mommy so badly that he anticipates her arrival at any moment and he assumes that anyone coming in from the outside is Mommy. A short, fat man wearing a baseball cap came in one afternoon to sell Mrs. Royer a new kind of cleaning fluid, and as he sprayed the stuff in his mouth to demonstrate how safe it was, five or six little heads bobbed up and greeted him with a cheery “Mommy!”

But every child knows who Mommy really is, and it is that knowledge that drives the main activity of the day: the waiting. Particularly for the one- to two-and-a-half-year-olds, the waiting is palpable, it is so intense.

The daily round of activities at the center is unrelenting, and children are easily distracted, but they are not fickle. Early in the day, Mommy is still a sharp memory, and her absence is mourned. There is a constant murmur of “Mommy, Mommy, Mommy” throughout the younger children’s rooms. By the middle of the day, consciousness of Mommy is at a low ebb; hunger has taken its place. But the wait is on again after nap time, when there is a chance that she’ll come back, and it takes on a new dimension altogether around 4. Then, some mommies—the nurses and teachers who get off work early—do materialize to whisk their children away. All through the afternoon the refrain at Here We Grow is “My mommy is coming. My mommy is coming.” By 5, any structured activity is in disarray, and the children are completely given over to waiting. Even the TV does not have a hold on them. They are patient, all things considered. Some of them still have an hour and a half to wait.

When a father or mother arrives, some children stare, as if in disbelief, for several precious seconds. Others have tantrums if the parent pays the slightest attention to another child. Others simply accept the parent’s presence calmly and unemotionally, despite the tension of the last hour. Clearly, Mommy is the one with whom the children rightfully belong, to their minds at least.

And, as it turns out, in the minds of the parents as well, the children ought to be home. No matter how good their reasons for putting the children in a day care center, parents carry an enormous burden of guilt about the decision. “It’s on our minds every single day,” Phyllis Bouquet says about leaving Kevin with Mrs. Royer. Day care is a difficult way to not stay home with a child.

Mrs. Royer says that what parents talk to her about most frequently is their feelings of guilt. She says she does not understand why they feel that way; she points out, truthfully, that some of her charges are getting better care at Here We Grow than they would at home. But Mrs. Royer did not send her babies away to a day care center, and neither did any of the other directors or owners of day care centers I talked to about their work. “I’d never send one of mine,” a woman who is a veteran of a national franchise told me. “I know what goes on in those places all day.” “Let’s face it,” said Mary MacInnis, owner of Grandma’s House, “no child is really happy in a day care center. It isn’t a home, it’s an institution. All we can do is make the best of things.”

The parents’ reaction to having to make the best of things is to rationalize that the amount of time they spend with their children is not as important as the quality of time. But in reality, quality time is rare. It cannot be planned or forced, and it cannot be counted on to happen according to schedule—right before bedtime, say, for convenience’s sake. Special moments crop up unexpectedly, and usually only after the ground between parent and child is prepared with a great deal of nurturing. Furthermore, as adults we tend to seek in our family lives not the highs, the heady moments when something unusual is happening, but constancy, a sense that a person will always be there. Why should children want anything different?

Day care is not a neutral solution to the problem of what to do with the children all day. It is changing the nature of family life. Just as parents bring the office home with them at the end of the day, children bring the center home.

Jennifer Schanhals’s father came to get her one afternoon, as he does every afternoon, at around 4:15. He is a big, bearded man, friendly looking and straightforward. When he arrived at Here We Grow, he made his way through a clot of children at the door and headed for the playpen room. As soon as he got to it, his daughter looked up and smiled at him. He melted and, covering the length of the room in two strides, scooped her up in his arms. He seemed a little intimidated by all the babies around him—they were underfoot no matter which way he turned—so one of the sitters went to get Jennifer’s coat and bottle and bag while he stepped into the hallway to wait. “This is the new world, man,” he said. “Just look around at all these kids. No keeping the mothers home anymore. The wife drops Jennifer off in the morning, I pick her up in the afternoon. None of that master of the house stuff anymore.”

Robert and Joyce Schanhals and their daughter, Jennifer, live in a house right down the street from the one in which Mrs. Royer ran her day home. The Schanhals residence is the second home that Robert, who is 32, has owned. He sold the first one, in Alief, for a good profit, but in spite of the deal he got on the new house, the monthly payments turned out to be hefty. He thinks he makes a good salary as a switch and equipment technician for Southwestern Bell, where he has worked for the twelve years that he has lived in Houston, but it isn’t enough.

He and Joyce, who is 28, decided she should go to work. Joyce had never held a job when she married Robert, and he was always after her to get one. “She was so naive and, well, sort of helpless,” he says. “Let me tell you what else, though. When you got a wife that sits at home all day, man, you got one boring woman on your hands.”

Joyce got a job in the service department of Xerox. After Jennifer was born, Joyce felt she had no choice but to continue working, so when Jennifer was two months old, the Schanhalses placed her in Mrs. Royer’s care. They had seen her ads in the newspapers, and her location was too convenient to pass up. When Mrs. Royer moved to the shopping center, only a few minutes’ drive from the Schanhalses’ house, Jennifer moved with her.

But Robert is not too comfortable with the idea of putting his daughter in a day care center. That was certainly not how children were raised in Bastrop, where he and Joyce grew up. It isn’t that he does not appreciate Mrs. Royer; he thinks she is excellent with children and has been great with Jennifer. But the house was one thing; the center is another. “Her setup seems better than most, but I don’t know,” he says. “It’s not the same anymore, all those children in that big shopping center. It’s like with McDonald’s, you know. Those burgers were great when there were only twelve restaurants, but now that they’ve got millions of them, they taste like hell.”

Furthermore, the economic justification for Joyce’s job is a close call. “These days we need all the money we can get our hands on,” he says, “but by the time you figure out how much it costs for the wife to go to work, I’m not sure it’s worth it. Car repairs, gas, clothes, day care—all that’s expensive and we only come out a couple of hundred dollars ahead each month. I guess it’s worth it for now. I just figure day care is a necessary evil.”

Chris and Sue Meeker, both 24, arrived together at Here We Grow to pick up their twins; Chris’s motorcycle was in the shop, so he and Sue were sharing their car. The Meekers live several miles from the Schanhalses, in a sprawling apartment complex off Kirkwood Road. They like the complex because everyone they know there is in the same position they’re in. “No one has any furniture,” Sue explains. “The chairs we’re sitting on belong to the lady next door. The twins sleep on mattresses on the floor.” When the Meekers aren’t visiting with friends, they are at home, because they can’t afford to do anything in Houston. They don’t feel it is a good place for families; everything costs too much.

Before the Meekers moved to Houston from Iowa, they had never considered putting their daughters in a day care center. Depending on who was employed at the time, either Sue or Chris stayed home with them. Sue, a warm, friendly person, had always been bothered by people who didn’t want to raise their own families. “With family bonds disintegrating everywhere,” she says, “I wanted to make sure the twins understood what a family is and how important it is.” She planned to keep her girls home until they were in first grade.

But Sue has a lot of work to do before she will be ready to help Chris realize his dream of opening his own land surveying business. He now has a job with Planning Research Corporation as a land surveyor; soon he will have his license and be registered. At her current jobs with an apartment management company, which buys and manages properties, and Evans Music City, where she does some bookkeeping on Saturdays, Sue is learning something about business, but not enough. She intends to take some courses at Houston Community College to learn how to run a company. The Meekers will run their business from their house—the one they are trying to save up for—and the house will be big enough for lots of office space.

When Sue realized she had to go back to school, she decided that her plans to stay with the twins until they went to school were unrealistic. She began to look into day care and settled on Here We Grow after dropping in on several centers. She liked its family atmosphere and the low registration fee. The first week at the center Christy and Jenny cried when she dropped them off, but she knew they would get used to it, and they did.

Now, when the twins see their parents at the end of the day, they won’t talk about what they do at Here We Grow. “They seem to reserve the time at the end of the day just for us,” Sue says. “Even though they are there eleven hours a day, they are bouncing with energy when they get home and often won’t sleep until ten or eleven o’clock.”

At 6:20 Phyllis Bouquet arrived to take Kevin home. Mrs. Royer asked to have a talk with her, and they spent about fifteen minutes going over a business problem. The Bouquets try whenever they can to help Mrs. Royer with her questions about finances; business is not her forte. Then Mrs. Royer shut off all the lights, and everyone went home.

Unlike the Schanhalses and the Meekers, the Bouquets—Eugene, 36, and Phyllis, 34—love their life in Houston and are already doing well enough to have seen one of their dreams come true. They are building a house in Barker’s Landing, a new 121-acre development with tennis courts, big yards, and lots of trees (but no landing) that is going up directly south of the intersection of Katy Freeway and Highway 6. Business has been clipping along at a healthy pace at Production Operators, the energy services company where Gene is treasurer and general manager of finance and administration. A genial, articulate, and frank man, he gives the impression of being extremely satisfied with his work. So does Phyllis, who at 24 became the first female petroleum engineer to testify before the Texas Railroad Commission and is now a vice president of sales for United Gas Pipe Line Company.

One thing the Bouquets made sure to include in their new, custom-designed home was quarters for a live-in maid. The cooking and cleaning are too much to handle at the end of a long day; besides, Kevin will be going to school in a few years and will have to have someone to come home to. They haven’t found a maid yet, and they have no idea how to begin screening applicants, or whether they will have to provide her with a car, or how they will handle any of the other details that go along with hiring maids; they just know they need one. “You don’t solve the problem of having children by finding an Isabelle Royer,” says Gene Bouquet. “That is only the first step in a very complicated process.”

The complicated process began when Phyllis turned thirty and decided to stop analyzing whether to have a baby and just jump in. She thought she’d hate herself if she didn’t, as she puts it, “give Mother Nature a try.” The Bouquets had waited to start a family until they had established themselves financially, taking advantage of the pill and of higher education (they each have an M.B.A.). As soon as Phyllis found out she was pregnant, she began to do some research on day care centers. She found Mrs. Royer through an ad in the paper, went to see her, and signed on. The Bouquets now think of Mrs. Royer as “too good to be true.”

Still, the Bouquets are not pleased that their son has been in day care twelve hours a day, five days a week, since he was eight weeks old. “I miss sixty hours a week with my child,” says Gene. “I’m missing the formative years. I feel cheated, but I stick to my decision to keep working. I’ve considered being a househusband—me and my buddies kid around about it sometimes—but I know I could never do it. And I’ve never taken the male chauvinist pig approach with Phyllis. I believe that a good marriage is based on mutual support and respect. It is hard to stop working when you have had a taste of success and have begun to build the self-confidence that comes from doing a job well. I have those feelings. Why should it be different for Phyllis?”

Phyllis went to her boss when she knew she was pregnant. At the time, she was being considered for a promotion. “Look,” she told him. “I know you are in a tough spot. If I were in your place, I would select me for the long term. But for the short term, I’m trouble. I am going to have this baby soon, and if it is healthy I will come back to work. If not, I don’t know.”

The short term turned out to be eight weeks. Phyllis got the promotion and returned to her job and a large corner office high up in the Pennzoil building. But it was not easy. “Isabelle became Mama, Gene was Dada, and for a while I didn’t know who I was,” Phyllis says. “I wanted Kevin to know that I was Mama, but at the same time I didn’t want to undermine his good feelings toward the person who took care of him all day. I finally convinced him he had two mamas, and Isabelle became the Other Mama. Of course, as the Mama I felt rotten.”

The Bouquets say their friends don’t really understand how they can raise Kevin properly in a day care center, but they are too polite to inquire about it directly. Gene often compares Kevin to other children his age and finds that he measures up just fine, “apart from a slight Spanish accent, which we’re working on.” In their old neighborhood, Phyllis and her day care child were quite a topic of gossip, with well-meaning neighbors dropping hints of disapproval, but the Bouquets can shrug that off now.

These days the Bouquets reunite in the evenings at around 7. Kevin has a bath, they all sit down to dinner, and then it is bedtime, Gene’s time to read to his son. Kevin is tired and often cranky at the end of such a long day, and his parents’ patience is somewhat limited. “We tend to take too many shortcuts with Kevin, because time is so precious,” says Phyllis. “We will clean up after him, or put him in his bath, or dress him, rather than let him do these things for himself. He’d be learning more that way, but it would take three times longer.”

Shortcuts notwithstanding, Kevin is a smart little boy and a natural leader. At the center, he is among the first to catch on to lessons. If he is bored, he will start his own games or songs, and others will join him immediately. Kevin does not seem to be suffering any ill effects from his day care life, and neither do most of the other children at Here We Grow. But it is hard to tell whether day care has changed a child when that child has grown up with it.

“I’ll tell you the worst part,” says Phyllis Bouquet. “I used to have to give Kevin a bottle early in the morning. I’d get up at five and spend a quiet hour holding him in my arms, just the two of us, before it got light out. By six I’d have to break that serene mood, put him down, wrap him up, and go out into a cold or rainy or dark morning to take him to Isabelle. I hated to part with my baby.”

I was born in 1955, and even though my mother stayed home to raise her children, by the time I was old enough to start thinking about marriage and careers I knew about day care centers. I was reading about them in magazines and newspapers and hearing about them in feminist groups, and I believed they were the solution to the problem of having a happy family life while working at a satisfying career.

And maybe they are the solution. Day care centers are certainly here to stay; coming out against them now would be like coming out against the automobile. Of the women in Texas who work, 84 per cent do so out of economic necessity (though that is loosely defined), but 28 per cent of those women are the sole supporters of their children. They need day care desperately. So do the thousands of adolescent mothers—of whom Texas has the second-highest number in the country—who have yet to finish high school or junior high or even elementary school. And day care centers provide a temporary haven for abused and neglected children.

Whether out of necessity or choice, many people have built their lives around being free of their children all day. But the growing dependence on day care is not without its consequences. That day care is rapidly becoming as important a part of a child’s upbringing as his family represents a radical shift in the nature of our society, one for which we are almost completely unprepared. We are rushing to day care centers, while in the countries that have been using them for a long time—like the USSR, Sweden, and Israel—there is growing concern over the negative effects that centers have on children who grow up in them. It is startling to find such overwhelming support of collectives of children in a city like Houston, among people who would not dream of living in communes or pooling food supplies to stock a neighborhood refrigerator. Has the child become a less important part of the family?

The ease with which those of us who have a choice can turn to day care—and find theories about what we are doing to assuage our guilty consciences—is distracting us from making difficult demands on our employers and on each other. Those demands do not have to mean that it is the women alone who must sacrifice their responsibilities outside the home. For many couples that would be too simple, too unfair, a solution. But two adults should be able to compromise their careers and lifestyles before they ask a child to compromise his childhood.

For many children, a childhood in a day care center is a compromise. I never realized this—and no one could ever have convinced me of it—until I spent long days at Here We Grow and saw children called upon to be in the same building, in the same room, for eight or ten or twelve hours a day. That’s something adults are not called upon to do until they are, well, adults.

Apart from whatever activity the teachers create for the children or what they create for each other, there is very little in their days that diverts their eyes, their imaginations. I was struck by this when I considered what my childhood would have been like had I not been able to go outside or be by myself for any significant stretch of time. Day care children do not often get to watch the movement of people on a busy sidewalk or the traffic in a crowded street. They miss falling under the spell of wind rustling through leafy trees or watching cloud shapes passing overhead. In other words, they are not being given one of the most significant things our parents gave us: a chance to discover the world alone, at our own pace, on our own terms.

Most day care centers—not all—are far from being evil places. But they are not good enough yet. Not if we want to give our children a childhood they will cherish for the rest of their lives and try to return to in some secret part of their souls.

Don’t Tell Them You’re Coming

How to choose a day care center.

There are so many day care centers in Texas that finding the right one for your child will seem an overwhelming task at first. It is hard work, but once you get started you will find that you can eliminate a lot of places before you even get in your car. When you set out to look for a center, plan to do some research by telephone first, then some legwork. Once you start visiting centers, keep in mind one thing: if you cannot imagine spending a day in the center, you cannot expect your child to stand it day after day.

Three kinds of child care are available in Texas: licensed day care centers, registered family homes, and unregistered facilities. (Unlicensed facilities are illegal, and operating one is a crime punishable by a fine of $1000 and a six-month prison term.) If you come upon an unregistered day care center or home—you can tell because it won’t have a registration certificate posted—report it to the Texas Department of Human Resources. These places can be dangerous.

Family homes handle a maximum of six children and are registered with the Department of Human Resources by mail; the requirements for registration are minimal. Unlike day care centers, family homes are not visited periodically by a state worker to see that they are meeting the department’s standards. Still, many parents prefer to put their children in family homes simply because they are homes and not institutions that keep 60 or 70 or 150 other children. The main thing to look for in a day home is a baby-sitter you can trust. Get references from people who have used the home, and then drop in unexpectedly. Cross it off your list if the TV is on and the children’s cries are being ignored.

If you’ve decided to use a day care center, first figure out your criteria in four basic categories: location, price, hours, and programs. Are you willing to pay more for a better educational program? Would you rather save $10 a week by driving an extra fifteen minutes to a center that’s less expensive than the ones in your neighborhood? In thinking about location, don’t forget to consider traffic. In Houston, for example, day care centers in office buildings are unpopular because no one wants to start the day stuck in rush hour traffic for an hour with a screaming baby. This sort of preparation will help when you open the phone book and are confronted with the wide variety of choices you have.

Pick out a good number of centers in the location you prefer, but don’t get in your car yet. You’ll see too many places you wouldn’t have considered for a moment had you called ahead, and you’ll get very depressed. Call first for information on hours, rates, and programs, and get the names of the people who run the centers. Make sure you ask about age limits; a lot of day care centers will not take infants under six months. Then decide which centers you want to visit.

If you have heard that a certain franchise or chain has a good reputation, don’t automatically assume that it is the place for you. Day care is not like fast food. Kentucky Fried Chicken might taste the same no matter where you buy it, but every branch of a day care chain will be different. Generally, the director of a place stamps her personality on it; meet the directors and judge accordingly. Find out if the chain has a policy of rotating directors from one location to another. If it does, the day care center you thought you had chosen might end up thirty miles away. The large chains tend to have a lot of money to spend on good supplies and sturdy, color-coordinated furniture and sometimes even their own buildings. But none of that is necessarily as important as the one thing money won’t buy—an affectionate, attentive sitter.

Once you’ve decided where to go, do not call ahead of time to make an appointment. You want your first visit to be unexpected; that is the only way to see what really goes on at any time of the day. You might have to go back to interview the director, but you can decide whether or not you want to after you’ve seen the place.

As you drive to the center, check out the neighborhood. Is there a hospital or emergency clinic nearby? Follow the route you will be driving to get to the center.

When you arrive, ask to go past the front desk. If the attendants tell you it is against regulations, you should take that as a warning that something is wrong (unless it is nap time, in which case they have a point). A good day care center has absolutely nothing to hide.

Use your eyes, nose, and ears. If the place smells awful, it is dirty; the garbage is not being taken out often enough. If the walls and floors are streaked with dirt, then the children are probably dirty too. Don’t believe any excuses about cleaning day coming up.

Watch what the children spend their time doing. Day care owners have lots of fancy words for the kinds of educational programs they are offering (“Montessori style” being one of the most common), but cutting and pasting paper shapes amounts to the same thing no matter what it is called. Also, keep your ears tuned for unhappy noises. Are crying children soothed quickly? Are whimpers ignored? Are you hearing too many unhappy sounds?

Check to see that any equipment the center might have—washing machine and dryer, for example—is working. Get a copy of the weekly menu, and visit the kitchen. Look at the bathrooms. Walk around the playground. Poke around in the supply closets. Don’t hesitate to ask to be shown anything you want to see. You are not in someone’s home; you are in an institution for whose services you will be paying.

Save some time during your visit to talk with the supervisor or owner, and ask these questions:

•What does the center do if the child is sick? Day care centers should turn a sick child away at the door—a bother for the child’s parents, but good for keeping everyone else healthy.

•What are parents expected to provide? Infant formula? Diapers? a toothbrush? A change of clothing? If the supervisors don’t require that, ask what they intend to do when a child soils himself. Make sure you are asked for written instructions for any medicine the sitter has to give your child. If you aren’t asked for instructions, neither is anyone else, and there’s no telling what kind of pills your baby will get. The more you are asked to do, the better off your child will be.

•How many of the children at the center are regulars, and how many are dropped off, say, once or twice a week? Children who are there infrequently have a hard time adjusting and often disrupt the other children’s calm.

•Who will be supervising your child? Meet that person and ask her how long she has been there and where she was working before. High staff turnover is one of the biggest problems in day care centers. Workers are usually paid the minimum wage, and many of them take a job in a center only long enough to make money for a special purchase; then they quit. It is extremely unsettling for a child to have several different sitters in the course of a year. That person might be just a sitter to you, but to your child she is Mommy.

•How many children and how many sitters are in each room? You might even get hold of the minimum standards handbook for day care centers published by the Department of Human Resources and compare what you’ve seen to what it requires for licensing.

There is a growing demand for all-night centers. If you are looking for overnight care, be careful—and sneaky. Use any tactic you can think of to check up on a place that will be keeping your child through the night. Make a surprise visit at 4 a.m. if you can take a break. Park in a lot nearby, and watch who comes and goes. An owner of one all-night place said she did just that to make sure her sitters weren’t entertaining their boyfriends at the center; she found out that many of them were.

Meet the sitter and ask what she plans to do all night. If she is reading or sewing or knitting, chances are that she’ll be awake at 2 a.m. and alert to the needs of her charges. Note the temperature in the center at night, and look over the obvious things like beds, blankets, and pillows.

Check up on the neighbors of an all-night center. I visited one that was in the same shopping center as a bar that stayed open late into the night. The child care center was used by people as a place to drop off the kids while they got drunk, and when those parents came to get their kids, everyone got waked up.

After you think you have found the place for you and your baby, do one more thing: try spending a day there. That is the only way to get a clue to what your child’s life will be like. D.B.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston