This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Last October, I had a baby. Well, not me exactly. But I did have something to do with the birth—I mean, besides that. During my wife’s labor, I was there in the labor room doing all those things fathers-to-be do in the modern age: offering moral support, timing contractions, filling paper cups with ice chips, the whole ball of wax. Then, because I had dutifully attended my Lamaze classes—another requirement for fathers-to-be in the modern age—I was allowed into the delivery room, where I had a front-row seat as my daughter came into the world. That part was great. The not-so-great part was the price of admission. Namely, the six interminable Saturday mornings spent at Lamaze class. Yes, heretical though it may sound, I hated my Lamaze class.

I didn’t start out with a bad attitude. Going in, I had a vague notion of what it would be like. Everybody does; Lamaze is now such a commonplace ritual of childbirth that, according to the American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in Obstetrics (the major organization that promulgates the Lamaze method), more than half of the expectant parents in this country attend childbirth classes of one sort or another. I knew that my wife and I would bring pillows and a blanket to use while practicing breathing techniques. I assumed that we would both learn important things about labor and delivery and get the facts we needed to make informed decisions about the birth of our baby.

But by the time the classes were over, I had changed my tune. By then, I had come to see that there was a lot more to Lamaze than learning how to breathe. Or should I say a lot less? My Lamaze class was instructive at times, but it was just as often silly, even counterproductive. Most of the fifteen hours I spent there seemed wasted. What struck me as far worse, however, was the way Lamaze tried to impose its own agenda on me and my classmates. Like most people about to have their first child, I went to Lamaze class a little naive and a little nervous, full of wonder and worry about what my wife and I had gotten ourselves into. Instead of setting me straight, laying things out objectively, Lamaze played upon my naiveté to promote its version of what “the childbirth experience” should be like.

So why was I there? In the first five minutes of the first class, my Lamaze teacher asked all of her students, one after another, that same question. (That’s the way they operate in Lamaze class.) For most of us the honest answer, though none of us said so at the time, was that we had no choice. Our hospital had an ironclad rule: if the father wanted to partake of the exhilarating experience of witnessing his child’s birth, he had to attend at least four of the six Lamaze classes. Our hospital was not unique in this regard; in the modern age, those are quite often the rules of the game. (For instance, of the seventeen big-city hospitals I called in Texas at random, eleven had the same rule.) Hospitals have given Lamaze a powerful club with which to beat expectant parents into submission. For the father who wants to attend the birth of his child—and for the mother who wants him to be there—the only thing worse than attending Lamaze classes is not attending them. Somehow it doesn’t seem right.

Before going any further, let me explain that I am not pining for a return to the good old days. In the matter of childbirth, the good old days were pretty much as the Lamaze people say they were: miserable. The great euphemism of that era was “twilight sleep,” a phrase used to describe the drug-induced state of a woman in labor. The mother would have only the haziest recollection of her child’s being born, and the way she found out whether the baby was a boy or a girl was by asking a nurse hours later. As for the father, he was the guy pacing around the waiting room. The only person who made out well was the doctor. With one parent in the waiting room and the other temporarily transformed into a zombie, there was no one to question him or second-guess him or otherwise complicate his life. Naturally, most doctors were strongly resistant to changing a system that served their ends so conveniently.

The great achievement of the Lamaze movement was that it broke the tyranny of the obstetrician. It offered an alternative to twilight sleep that, once it caught on, steamrollered any obstetrician who stood in the way. What Lamaze had going for it was, first of all, a scientific and sensible solution to the trauma of the good old days—the controlled breathing that allowed women in labor to remain “awake and aware” (to borrow from the title of an early pro-Lamaze tract). The technique, called psychoprophylaxis, was first devised by the Russians in the thirties and forties and became popular in Europe in the early fifties, in large part because of the proselytizing of a French obstetrician named Fernand Lamaze. The theory is that controlled breathing during labor can short-circuit the signals of pain being transmitted from the woman’s uterus to her brain. Thus the woman is able to ward off enough of the pain to stay fully conscious. (Dr. Lamaze was a trailblazer in other ways as well; the title of his book, Painless Childbirth, set a standard for less-than-full disclosure that the Lamaze movement still adheres to.)

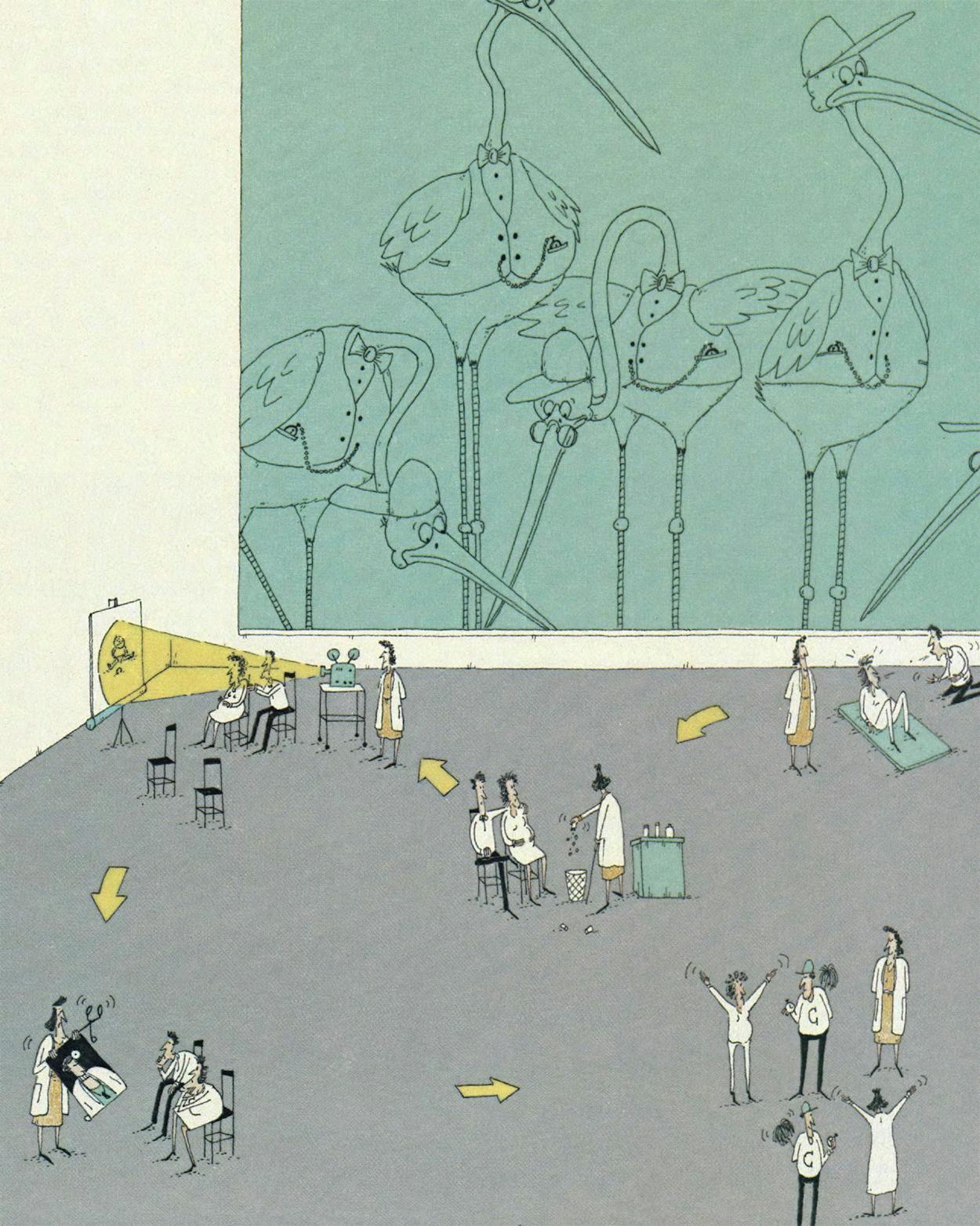

But alas, controlled breathing is only one part of the Lamaze agenda. My class, for instance, spent less than one fifth of each session practicing the breathing techniques. The rest of the time was spent learning, to quote Awake and Aware, “to decondition erroneous ideas about childbirth and to develop correct and worthwhile attitudes to replace them.” If that sounds a little like something Chairman Mao might have written, it doesn’t get any better when you live through it.

The reason I came to dread my Lamaze classes was that they were selling correct and worthwhile attitudes just as much as they were selling controlled breathing.

And many of these attitudes were so “late sixties” as to be painful. I never did cotton to the idea, for instance, that the best way to get ready for childbirth was to “share my feelings” with my instructor and the rest of the class. Neither did most of my classmates, I might add. As far as I was concerned, sharing my feelings with 21 strangers was only going to make me more anxious than I already was.

But my main complaint was that Lamaze’s correct and worthwhile attitudes struck me much of the time as quite wrongheaded. The key tenet for the Lamaze faithful—the one principle from which all else flows —is that childbirth should be kept as natural as possible. But this ethos is at the heart of what is wrong with Lamaze. It promotes the completely natural birth as the ideal, the standard against which we are to judge our own experience. Very little support is ever given to the idea that completely natural childbirth might not be right for everybody. At a time when we are making some of the most personal decisions of our lives, Lamaze is trying to tell us that there is a particular way we should think and act. In a sense, the tyranny of the obstetrician has been replaced by the tyranny of Lamaze.

Of course, no one who teaches or writes about Lamaze will admit that. All the literature I read went to great lengths to deny any sort of bias. In my own class, the teacher was horrified when I asked her why she had such an antimedication bent. (Though after she recovered enough to deny the charge, she did thank me for sharing that feeling with her. Arrrggghhh!) But when you look at what actually goes on in class, it becomes clear that in a dozen different ways, some subtle and even sneaky, some not, the message is transmitted, though always in the guise of a free flow of information. Shall we describe a few of them?

1. The medication myopia. The word “medication” was once practically synonymous with twilight sleep. Not anymore. In modern obstetrics, medicine is used primarily to ease the pain of the woman in labor. She is still very much awake; she just doesn’t hurt so much. Why this is so terrible is beyond me, but our teacher made it implicitly clear that terrible it most certainly is. To her it was a point of pride that she had used no medication during the births of her last two children. She had toughed it out, and it had been worth the price. She obviously hoped the women in the class would do the same.

Consider the way she introduced us to a procedure called an epidural block, in which an anesthetic numbs the legs and abdomen during labor. First she passed around to the class a sheet listing the various anesthetics and medicines commonly given during labor. Under a column headed “Possible Disadvantages,” this is what was listed for the epidural: “30 min. to take effect. May slow or stop labor. May need labor stimulation. Increased use of forceps. Maternal drop in blood pressure, chills, shakes, nausea, vomiting, rare seizures or headache . . . Baby may have poor muscle tone.” Sounds pretty awful, doesn’t it?

Then she began talking about her own experience with an epidural (she had had one for a surgical procedure immediately after the birth of one of her children), and the implicit was made explicit. “Oh,” she said, “you just don’t have any control over your legs. I remember thinking how uncomfortable that made me feel.” One of my classmates asked her why having an epidural was any different from being given novocaine at a dentist’s office—or any more harmful. She seemed stunned that someone would not automatically agree that numb legs were bad, but other than that she had no ready answer.

The truth is that while there are some risks associated with epidural blocks —as there are risks with any medical procedure, from allergy shots to brain surgery—the potential benefits usually far outweigh those risks. This particular anesthetic has become quite commonplace during labor not because doctors are ogres but because it is a relatively simple, relatively safe anesthetic that can do a lot of good. Much of the time it is used because the woman has decided she can’t tolerate the pain anymore. And while there are times that it does slow down labor, there are other times when it is used to do just the opposite: to get a slow-moving labor going in the right direction. For a premature baby, an epidural makes the birth less traumatic. But I didn’t hear any of this in Lamaze classes. On the sheet my class received, there was no list for possible advantages of medication, and it always seemed to me that they were assiduously downplayed.

There is another, more insidious reason that medication was frowned upon in Lamaze class. Namely . . .

2. You’re hurting your baby. You want to use a painkiller during labor? Fine, the argument goes—though it is never stated nearly this blatantly—but don’t blame us when after the delivery you find you have a . . . groggy baby!

Is a little grogginess really so terrible? As far as I can tell, the answer is no. It seems that once again, the Lamaze assumptions are rooted in the way things used to be rather than the way they are. “When I was practicing in Washington in the early fifties, the sedation that was used in childbirth was criminal,” said one doctor I talked to. “It was used in such large doses that almost every baby in our hospital had to be resuscitated. The oversedation of patients was a serious problem.” But today it’s not. These days most doctors administer Demerol, a common analgesic, in about one twentieth of the dosage that was used in the fifties, and the effect on the baby is minimal.

Indeed, Lamaze never does make much of a medical case against groggy babies. The case Lamaze does make is more in keeping with its hidden agenda: whatever is more natural is therefore, ipso facto, superior. It’s just nicer.

3. The information illusion. Here’s my favorite example of how the “facts” are presented in Lamaze class. During my fifth class we were all handed a four-page pamphlet entitled “The Circumcision Decision.” It was written by Edward Wallerstein, who was described as the author of Circumcision: An American Health Fallacy. (To establish his credentials further, the pamphlet also stated that he had discussed circumcision on Donahue.)

Wallerstein is not exactly Mr. Nonpartisan on the subject of circumcision. What he has written is a diatribe against the practice, in which it is made clear that all right-thinking people must oppose it (unless their rationale is religious). He labels it an “archaic practice”; he says it may lead to something called circumcision trauma; he tells us that “most babies scream during the operation” and that there are “attendant risks, e.g., human error, excessive bleeding, infection,” and a host of other ills. “One thing is certain,” Wallerstein notes ominously, “circumcision is not innocuous.”

Maybe circumcision is, as he writes, “a solution in search of a problem.” Still, his polemic is so one-sided that I wondered if there was another side and what it might be. Later I learned from friends who had little boys and had done some research into the subject that mainstream opinion holds that circumcision is fairly innocuous, although admittedly the reasons for doing it are more cultural than medical. But Lamaze won’t concede even that much. At a sixth class I attended (not my own), a woman asked her teacher whether the circumcision pamphlet hadn’t been a tad slanted. “Well, it was pretty emotional,” she replied. “But you have to look past the emotions to the facts. Everything he wrote is factual.” End of discussion.

Again and again the proponents of Lamaze tried to steer us in the direction they wanted us to go instead of laying things out and letting us decide for ourselves (though again, they claim to be doing just the opposite). In that sixth class I attended, for instance, the issue of bottle feeding versus breast feeding came up. “A lot of women prefer bottle feeding, and that’s fine,” said the teacher. “But . . .” and then she trotted out her litany of reasons why breast feeding was better. Of course, breast feeding is better—I know that. What was troubling about the litany was its tone, its insinuation that those who didn’t breast-feed were not being good parents. And yet there are mothers who can’t breast-feed, and there are babies who prefer the bottle to the breast. Should those mothers have to feel guilty because of that? It seems to me that this particular Lamaze technique—asserting that there is nothing wrong with option A but then weighing the scales so heavily in favor of option B that only the most heartless parent would choose option A—induces precisely that sort of needless guilt. And once you’ve heard a few choices framed in this fashion, you begin to doubt that you’re getting the straight dope about anything.

4. Don’t trust the doctor. This is the Lamaze version of fighting the last war. In the old days, it was tough to get obstetricians to take Lamaze seriously. It took women who demanded that their doctors allow them to use controlled breathing during labor, and it took husbands who were equally insistent that they be allowed in the labor and delivery rooms. Things could get pretty nasty, and one of the main tasks of the Lamaze teacher was to give parents the push and the ammunition they needed to stand up to their doctors—never an easy thing to do.

But now the battle is over. Lamaze has won. Today there is hardly a hospital in urban America that doesn’t have a maternity setup that allows for controlled breathing and for participating fathers, and there is scarcely an obstetrician left who objects to Lamaze.

Yet Lamaze seems incapable of changing its tune, of working with doctors instead of against them. Lamaze is still steeped in the rhetoric of “us versus them”—“them” being the big, bad, uncaring hospitals and the equally uncaring doctors who don’t want you to upset their routine. My teacher tried to stiffen our spines, implying that the doctor and the hospital would roll over us if we didn’t push back. But in my experience, both the doctor and the hospital nurses were a pleasure, full of no-nonsense information and advice, and that made the nagging of the Lamaze teacher seem all the more regressive.

5. Excessive euphemisms. The one that drove me craziest was “Coach.” That’s the Lamaze word for the childbirth partner. After you’ve heard yourself called Coach a few dozen times, it has the same effect as a fingernail on a blackboard. The word is so patently designed not to offend that it offends for that very reason—kind of like “peacekeeper missiles.”

But the euphemisms that really grate have to do with labor itself. No Lamaze teacher wants to reveal the most obvious fact of all about labor: it hurts. The theory behind this reluctance apparently is that if you don’t think it will hurt, then it won’t. According to the author of Awake and Aware, “one never speaks of ‘labor pains’ but only of ‘uterine contractions.’” In my class there were several times when the instructor did admit that yes, it might hurt. Since two women in our class had had children before and were willing to set the rest of us straight, she didn’t have much choice. But mostly she used the term “discomfort.” It was so much easier on the ear—and so much more disingenuous.

6. They use forceps, don’t they? The way Lamaze promotes its point of view can sometimes be quite subtle. A teacher brandishes a pair of forceps so everyone can see how menacing they look. (“Now sometimes the doctor has to use forceps, and that’s all right. But . . .”) There are weekly films, in which all the parents strive mightily to go natural and then applaud themselves (and their wonderful Lamaze teacher) when they succeed. There are little throwaway comments about “seeing how far you can go without an anesthetic.” These say more about Lamaze’s set of values than a dozen out-and-out manifestos.

The sad part is that so many people buy the Lamaze line without ever really thinking about whether it makes sense or not. The time I spent in Lamaze class made me realize how vulnerable new parents are. Having never had a baby before, they—we—are perfectly willing to believe that there is a right way to do it. Our naiveté is what makes us so susceptible to the Lamaze pitch. And that can set us up for a big fall.

During my wife’s labor, the nurse and I got to talking about Lamaze (we coaches can have a lot of free time on our hands). Although the nurse strongly believed in the efficacy of controlled breathing, she was troubled by some of the things that were taught in most Lamaze classes. She was in a position to see every day what Lamaze had wrought. She saw, she said, mothers who sometimes—quite a few times, in fact—felt they had failed at childbirth just because they had broken down and used an epidural block to get through labor. There were fathers who pushed their wives to avoid an anesthetic even after the labor had become intensely painful. There were even times when the desire to do things the Lamaze way could cause unnecessary complications—when, for instance, the doctors felt it was necessary to use a certain medication and the parents, trained by Lamaze to be skeptical of anything doctors said, resisted. How does that do anybody any good?

About halfway through that sixth class I attended, a mother and father came in with their new baby. They had been in the class, but the baby had been born before they could complete the course; now they were returning to “share their experience” with their former classmates. What this proud new mother was proudest of was that she had not taken any painkillers. I asked her why it mattered. “I wanted to be strong for my husband,” she said. “I wanted to be able to say I had done it myself. I would have been very disappointed in myself if I had had to use Demerol.” This is the ethic instilled by Lamaze: Superwoman endures the pain for the good of . . . what? That part is never made clear.

In theory, it wouldn’t take much to reform Lamaze. Parents would want to continue learning controlled breathing, of course, and they would also want important information presented in an impartial way. The rest of it they could do without. My guess is that most of what anyone needs to know could be packed into one three-hour class. (Such an arrangement would also have auxiliary benefits. One problem with going back to Lamaze class again and again, for six weeks in a row, is that the very act of returning to class tends to heighten the tension and anxiety instead of dispelling it.) I have a friend in Washington who because of a crushing work schedule arranged to have a Lamaze-trained nurse come to his house one night and give him and his wife the essentials in three hours. A short course worked fine for him, and it could work for the rest of us.

As for the hospitals, they could do their part by eliminating the no-classes-no-delivery-room rule that gives Lamaze so much of its authority. After my child had been born, I called my hospital to find out why fathers were required to take Lamaze classes in order to witness the birth. The answers were pretty hollow. First, said a hospital spokesperson, the hospital wanted fathers to have some idea of what they were going to be seeing. Nothing wrong with that, I suppose, except that only a small sliver of the fifteen hours of Lamaze class was devoted to what happens in the delivery room. Second, she said, the hospital wanted to see some “commitment” on the part of the fathers. For me, this was the final blow. Had I plodded through all those Saturday mornings just to prove I could tough it out? After all the shared feelings, the propagandizing, the insinuations and guilt inducements, it turned out that endurance was what really mattered. Lamaze has become a kind of prenatal hoop-jumping.

I know that Lamaze won’t be reformed overnight, no matter how many of us rise up in protest. It has become so entrenched, so much a part of the system, that it has no incentive to change. And the hospitals have no incentive to change either, unless someone decides to make a federal case out of it. (Now that I think of it, wouldn’t it be interesting to see how the no-classes-no-delivery-room rule would hold up in court?) But then, that’s the way it usually is with monopolies. Which is another reason I hate Lamaze.