“You can change the name of an old song

Rearrange it and make it swing . . . ”

— Bob Wills, “Time Changes Everything”

What goes around comes around: one of the most critically acclaimed albums of recent years was The Pine Valley Cosmonauts Salute the Majesty of Bob Wills, featuring a bunch of postmodern pickers from Chicago (some via England); this year, Asleep at the Wheel’s Bob Wills tribute, Ride With Bob, with an all-star country cast sitting in as guest artists, won two Grammy awards; and the swing influence leaps from the music of all manner of Texas country circuit riders, from Ed Burleson to Clay Blaker to Don Walser to Johnny Bush. Sixty-five years after his first recording sessions with the Texas Playboys, 25 years after his death, Bob Wills is still the king.

It’s tempting to chalk up this indisputable fact to the swing-dance revival of the past few years, but that’s only one factor. Remember that Wills enjoyed a comeback of sorts once before, in the early seventies, spurred by Merle Haggard’s heartfelt A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World. Out of this resurgence came the Haggard-organized Playboys reunion album For the Last Time (Wills was so ill at the time that he could only watch the sessions), the birth of the “new” Willie Nelson and the outlaw country movement, Asleep at the Wheel, Alvin Crow, George Strait, and the like. In the mid-eighties the boom manifested itself primarily in the number of western swing festivals and associations in the Southwest. Today Wills is being resurrected by mainstream country stars like Beaumont’s Tracy Byrd, alternative-country stalwarts like Englishman Jon Langford, and swing diehards like Fort Worth steel player Tom Morrell and Big Spring bandleader Jody Nix.

In a sense, the history of “San Antonio Rose,” perhaps Wills’s most enduring song, serves as a metaphor for his career and illuminates all the conflicts at play — urban versus rural, pop versus traditional — in his life and times. In 1927, while living in New Mexico, Wills wrote a mariachi-flavored fiddle instrumental called “Spanish Two-Step” after realizing that the local Chicanos weren’t dancing to his more traditional fiddle breakdowns because the beat was wrong. He recorded the song in 1935 at the first Playboys session. Caught unprepared when asked three years later to come up with a similar tune, he rearranged “Spanish Two-Step”; since he didn’t have a title for the new instrumental, he accepted the suggestion that it be called “San Antonio Rose.” By the spring of 1940 the song was so popular that the publishing company owned by Tin Pan Alley tunesmith Irving Berlin offered Wills a $300 advance to provide lyrics (which he wrote with his trumpet player, Everett Stover). The Playboys quickly recorded this updated version as “New San Antonio Rose,” while the publishers, thinking the song wasn’t mainstream enough, rewrote the music and the lyrics. Wills had to sic his attorneys on Berlin, Inc., to get the song published the way he’d written it; Bing Crosby then made it a million-selling pop hit in 1941. Thus did a commercial fiddle tune based on another commercial fiddle tune based on a traditional fiddle tune, only with more of a Mexican flair, turn into a country-pop lyric that had to be changed back from a straight pop lyric before becoming one of the era’s biggest pop hits.

The explanation for Wills’ staying power has to begin with his boundless music and dominating presence. With the exception of zydeco (think Clifton Chenier), no genre has been so fully identified with a single person. This remains true even though Wills, contrary to popular opinion, is not the father of western swing. That title belongs to singer Milton Brown of Stephenville. The two men met in 1930, soon after Wills, already a pretty fair breakdown fiddler, arrived in Fort Worth from the Panhandle town of Turkey. They began playing together (with guitarist Herman Arnspiger) in a group that would become known as the Light Crust Doughboys. Brown left to form his own band in 1932 because Doughboys boss W. Lee O’Daniel — the president and general manager of the Burrus Mill and Elevator Company, which sponsored the band, and a future Texas governor and U.S. senator — wouldn’t let the musicians play dances.

It was the Depression; it was the Jazz Age. O’Daniel aside, Texans wanted to dance. At the Crystal Springs Dancing Pavilion, just outside Fort Worth, the five-piece Milton Brown and the Musical Brownies quickly evolved into a “hot” string band, playing jazz, blues, and pop standards on what were considered country instruments. Brown sang in a warm, intimate style that drew anyone not dancing to the lip of the bandstand to watch. By the time the Brownies entered a recording studio in April 1934, they’d added a piano, and soon there was also a second fiddle and Bob Dunn’s maniacal steel guitar. Wills was watching. In 1933 he left the autocratic O’Daniel’s Doughboys, taking with him Tommy Duncan, the smooth singer who’d replaced Brown. To escape the shadows of both O’Daniel and Brown, Wills went first to Waco, then to Oklahoma City and on to Tulsa, where he added horns, drums (unheard of in a string band), a piano, and a steel guitar; the original Texas Playboys took shape. But by the time the Playboys first entered a studio, in September 1935, Brown’s band had already cut more than fifty sides in the style now recognized as western swing. Had he not died following an April 1936 car wreck — his funeral drew more than three thousand fans — Milton Brown, not Wills, might still be king.

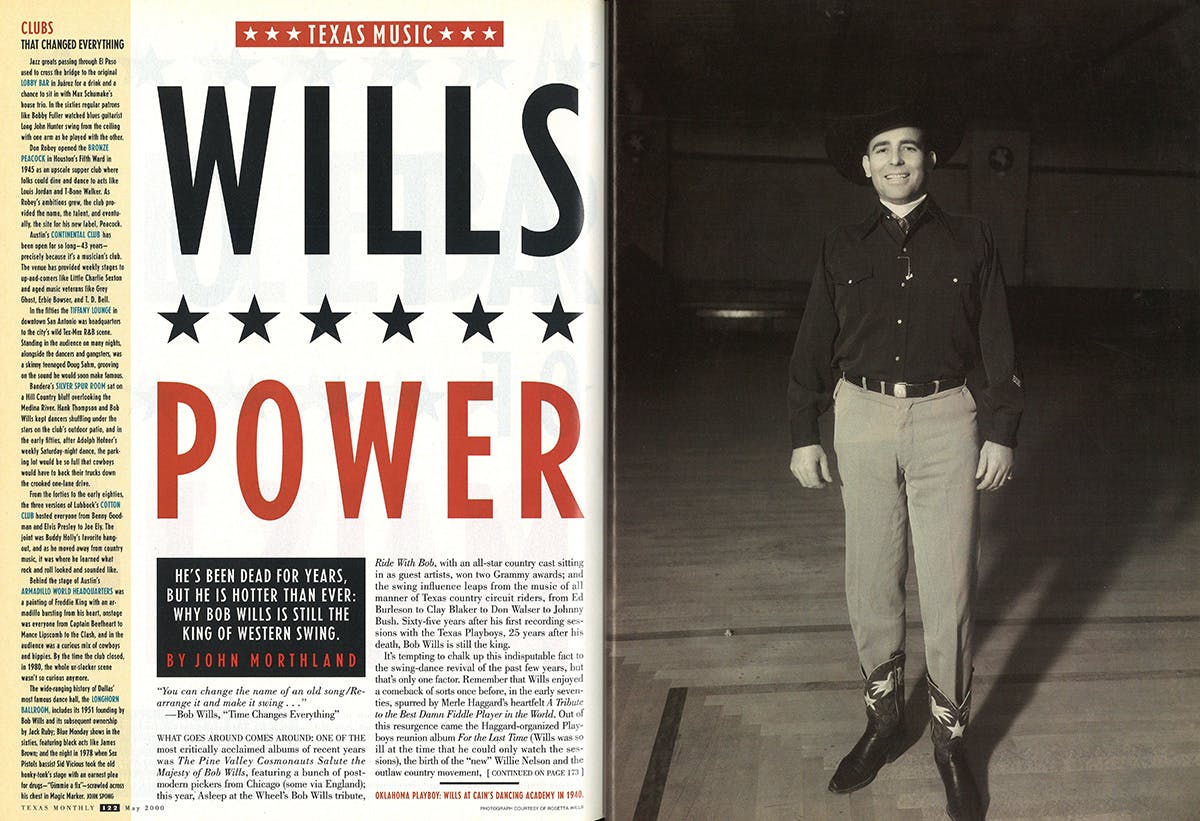

Then again, who can say if Brown would have been able to match Wills’s resourcefulness? With sophisticated guitarist Eldon Shamblin serving as their musical director, Wills and the Texas Playboys quickly moved further and further away from the string band sound, taking a staggering variety of music, rearranging it, and making it swing. Their repertoire — said to be 3,600 songs — came to include traditional fiddle tunes, commercial country, waltzes, boogie-woogie, blackface and minstrelsy, gospel, cowboy songs, polkas, New Orleans jazz, two-steps, schottisches, blues, pop, classical, Mexican-flavored songs, and more. Along with Tulsa radio station KVOO, Wills’s base was Cain’s Dancing Academy, and his music was strictly for dancers (unlike Brown, who had also played concerts). In fact, the Playboys performed each selection twice in a row — the first time so dancers could find the groove, the second so they could hold it. Though Wills featured the occasional sad song (one of the saddest, “Faded Love,” became a calling card), his music was largely upbeat at a time when working people, especially, needed a respite from their everyday economic conditions.

Though featured musicians like Shamblin, steel guitarist Leon McAuliffe, pianist Al Stricklin, saxophonist Zeb McNally, and fiddler Jesse Ashlock were undeniably skilled both as soloists and as ensemble players, the music never got slick; it was raw and from the heart, and at its core there was always the earthiness of the leader’s plaintive country fiddle. With their two front lines — one of fiddles, one of horns — Wills and company were like nothing else in America. As the Jazz Age evolved into the big band era, the Playboys grew to 22 pieces, playing songs like “Big Beaver” with a polish and a drive equaling that of the orchestras of Glenn Miller or Tommy Dorsey. But the music always retained its spontaneous, improvised feel (to this day, Wills veterans like fiddler Johnny Gimble insist their music is more properly Texas swing, which is always improvised, rather than western swing, which isn’t necessarily).

And then there was Wills, who had charisma to burn. Onstage with his musicians, all decked out in stylish band uniforms — the western clothes and cowboy hats came later — he was a bundle of high-spirited energy, directing soloists, cuing the band, joking and jiving, letting fly his trademark “a-ha” when the spirit moved him, riding herd on that monster sound, coaxing it and shaping it and letting it rip with a smile on his face and a fat stogie in his mouth. His personal style, like his music, was infectious. Between sets, he required his musicians to mingle, shake hands, and chat with audience members about their families, jobs, crops, and cattle. This was obviously good business — especially when the band returned to the same gig months later and could call folks by name and ask after their kids — but it also reflected his personality; he was genuinely humble, and there were few airs about him. His stylish success lent his fans a sense of dignity and class that nobody else accorded them. In return, they related to him like family; parents often brought their kids in baskets, which they placed on the edge of the stage for safekeeping while they danced. When Wills got too drunk to play, an increasingly frequent situation as his career went on, the Playboys would announce that he was sick, and the audience would nod knowingly, laugh and poke each other in the ribs, enjoy the show, and go home happy; when he was sick, the band might say that he was too drunk to show up, and the dancers would have the same reaction.

At the same time, he was fiercely protective of his music. Though strictly a country fiddler himself, Wills always insisted that his band didn’t play country music, it played jazz (the term western swing wasn’t introduced until after World War II). When “legit” (as they were called) musicians mocked the Playboys, Wills shut them up by noting, “Nobody likes us but the people.” He knew what he wanted and he knew when he had it and nobody was going to interfere. When Uncle Art Satherly, the legendary British talent scout and producer, first came to Dallas from New York to record Wills in 1935, he was apparently expecting a fiddle-and-guitar band and objected when he saw musicians pulling out horns; once they began playing, he didn’t like Wills’s whooping and hollering. Wills threatened to cancel the session if Satherly wouldn’t do things his way, and the big-city bigwig backed down. In 1945, when the Playboys first appeared on Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry, Wills was instructed as the band set up that drums were forbidden; again, he simply told the band to start packing up, and again an exception was made. Back in those days, nobody talked back to a label or the Opry, but Wills did, and he won; drums, twin fiddles, amplified guitars, even horns, were eventually accepted as country instruments.

These scenarios were played out again in the seventies by Willie Nelson, when he turned his back on Nashville’s country conventions and came home to Texas to make his music for his audience, and they get played out today every time a progressive Texas country musician — Lyle Lovett, say, or Junior Brown — breaks through without first taking up residence in Nashville. Like the Texas Ranger who was in the right and kept on comin’, Wills stuck to his guns, both musically and personally. That’s what people responded to then, and it’s what they respond to now. Even after the war, when his original band was scattered and he chose to move to California with new musicians, he provided the ultimate Texan image to go along with the ultimate Texas music. His music has endured because it sounds as original and as soulful now as it did then, because it so fully reflects the cultural polyglot that Texas has been throughout the past century, and because Texans (unlike Southeastern country fans, who’ve always preferred concerts) still like to dance. And because as sweet as Wills could be among fans and friends, he was also the rebel who had to do things his way when he ran up against the Nashville and New York music businesses. Texas, he seemed to say, was its own place, and Bob Wills was his own man.

Essential Listening

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Anthology (193501973) (Rhino)

Milton Brown and the Musical Brownies, The Complete Recordings of the Father of Western Swing (Texas Rose)

Asleep at the Wheel, Ride With Bob (Dream Works)