This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The plugs on the back cover are the sort of testimonials every author longs for.

“Warm, wise, wonderful tales by the greatest orator in the House of Representatives,” says Martin Tolchin, Washington correspondent for the New York Times.

“All Americans should read this book,” says John Silber, president of Boston University.

“Jim Wright proves once and for all in this book that you do not have to be boring and sanctimonious to be a successful public man,” says Jim Lehrer of the MacNeil-Lehrer Report.

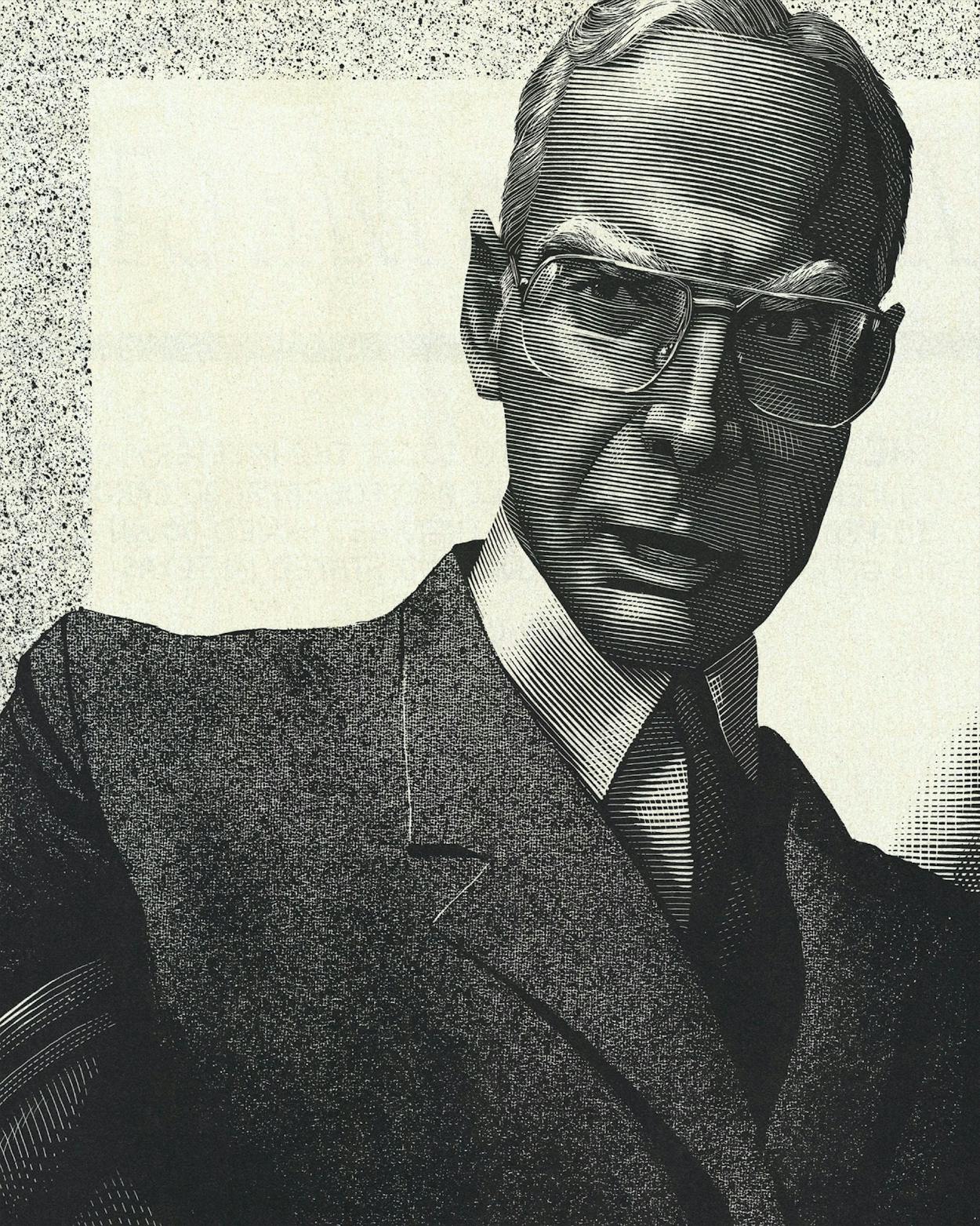

The accolades are for Reflections of a Public Man, a collection of Jim Wright’s musings and favorite anecdotes that was published in 1984, two years before he became Speaker of the House. If only the fulsome praise on the back cover were true, Wright might not be so politically wounded today. The cover blurbs notwithstanding, Reflections of a Public Man is a homemade paperback that would shame many vanity presses to publish. Its 117 pages include gaping white spaces and one editor’s note, though nowhere is there any mention of an editor. The book received almost no notice at the time it was published, but the current furor over Wright’s royalties has turned it into something of a collector’s item in Washington. The circumstances surrounding its publication are largely responsible for the official House investigation into Wright’s ethics that has absorbed Washington for two months.

The details of the unusual agreement between Wright and his publisher are well known. For each $5.95 book sold, Wright received $3.25—representing a 55 percent royalty, a nifty markup over the usual author’s share of 10 percent. The publisher, Carlos Moore, is a Fort Worth printer and longtime Wright political ally who does campaign work for the Speaker. Moore is also a political consultant. Here things begin to get sticky. In the two years following the book’s publication, Moore’s companies did more than $250,000 worth of business for Wright’s reelection campaign. Things get stickier. Many of the books were sold in bulk to Wright’s political friends. Former Texas agriculture commissioner John White, now a Washington lobbyist, bought a thousand copies. So did the political action committee of the Teamsters union.

A person of suspicious mind might conclude that this transaction reeks. One such person was conservative columnist George Will of the Washington Post, who wrote, “One does not need a moral micrometer, or a congressional investigation to recognize that the book looks like a money-laundering scam for lining Wright’s pockets with campaign funds.”

The book deal is one of six allegations against Wright currently before the House Committee on Standards of Official Conduct, commonly called the ethics committee. Of the remaining charges, the most serious is that Wright intervened with savings and loan regulators to seek special treatment for Texas institutions owned by Democratic campaign contributors. As Washington transgressions go these days, the charges against Wright are not a major scandal. They are magnified because they come at an awkward time for Wright and for his party, in an election year when the Democrats are exploiting the sleaze issue—Ed Meese and other malfeasants.

As damaging to Wright as the official investigation are the unofficial questions the episode raises about his stature as a national leader. Washington is down on Jim Wright. He is under fire for the way he runs the House and for the kind of people he keeps around him, as well as for his finances. Ever since the Fort Worth congressman rose to prominence as House majority leader in 1976, two issues about his character have persisted. One involves his ethics—whether he is part of the sleaze issue. The second involves his judgment—whether he is big league or bush league. Wright’s ethics will be weighed in the open by rigid legal standards that work to the advantage of the accused. His judgment is already being weighed in private conversations and cocktail party gossip all over Washington, a town that knows no mercy for the afflicted. And the verdict is not favorable.

The book that is behind Jim Wright’s problems is not a book at all but a collage. It consists of 75 excerpts from his speeches, writings, tales, and journal notes that have been cut and pasted together. Still, Reflections of a Public Man is fascinating reading, though not for the reasons given by Tolchin, Silber, and Lehrer. It is fascinating because it catches a high-ranking politician in the act of committing intellectual suicide.

Wright takes civic textbook wisdom and boils it down even further; his book compares to serious political writing as Muzak does to Mozart. Here in its entirety is one of the selections, titled “The System”:

What people really mean when they say “the system isn’t working” is simply that they are not getting their way.

The system assures that each of us may have his say. It does not guarantee that any of us will get his way.

All that is missing is a concluding line like: “And that is a thought worth pursuing.” Unfortunately for Wright, he already used that to conclude a selection called “Some Thoughts on Posterity.” The thought worth pursuing was:

My father used to say to me: “Jim, if you are only as good as I am, that isn’t nearly good enough. If you do not achieve more than I have achieved, then I will have failed. Unless each generation makes some improvement over the generation before, there is no point to posterity.”

This tale may very well qualify as wise. No doubt the audience who heard it from the greatest orator in the House of Representatives regarded it as warm. But reduced to writing, it is something short of wonderful. Like so much of Reflections of a Public Man, it is merely a cliché. Patriotism, Wright says, is thinking more of our rights than of our wrongs and more of our duties than of our rights. Bad news drives out good news. When you fall off a horse, you’ve got to get back on. Sam Houston’s faults were big, but his faith was bigger. And so on. As Wright himself writes in an anecdote about a professor who criticized his too-ornate prose, “Jim, the purpose of words is to reveal thought—not to conceal thought.”

One of the charges against Wright is that a member of his staff, Matthew Cossolotto, spent two hundred office hours working on the book. Wright’s defense is that Cossolotto put in his full forty hours of service a week for the government in addition to working on the book. Wright might have added in rebuttal that no one could have spent two hundred hours on this book. One thing is certain: There will never be controversy over whether Cossolotto wrote Reflections of a Public Man, as there continues to be controversy over whether Ted Sorensen ghosted Profiles in Courage for John F. Kennedy. The greenest staffer on Capitol Hill would not have turned in a manuscript with a selection like “Thoughts on a Mexican Sunset”:

I stood and watched the sun descend

To ocean’s rim past Acapulco Bay

And felt I must be nature’s friend

Thus entertained in such a regal way

(To take it in one almost had to pray).

One does not have to be a literary critic to wonder why Jim Wright put his name on this book. At the time that he committed authorship, Wright was one term away from becoming Speaker, a position behind only the vice president in the line of succession to the presidency. He had spent three decades in Congress, an arena where the lowliest first-termer quickly learns that respect translates into power—and a lack of respect into a lack of power. Two explanations come to mind, neither of them very kind to Wright. One is that he did not know that the book was an embarrassment. The other is that he wanted the money so badly that he did not care.

For anyone involved in a political scandal, the appearance of wrongdoing can be as ruinous as outright illegality. This axiom, as old as Caesar’s requirement that his wife be above suspicion, is particularly applicable to post-Watergate Washington. Once a politician begins to be the regular focus of disparaging stories on the front page and the network news—when, as has happened to Jim Wright, his picture is juxtaposed with Ed Meese’s in the national news magazines—his credibility is shredded and his ability to lead is diminished.

Wright steadfastly maintains that he has broken no House rules, and in all likelihood he is right, though that may say more about the rules than about Jim Wright. But he has violated an unwritten political rule by being heedless of appearances. At a time when congressmen are more careful, if not necessarily more ethical, than their predecessors of twenty and thirty years ago, Wright seems to be a throwback to another era. His carelessness about propriety, his rhetorical flourishes that can border on sanctimony (Jim Lehrer notwithstanding), and his obvious discomfort on television add up to an image that does not go over well in modern politics—that of an old-style Texas pol.

The question that is doing Wright the most damage in Washington is how he could have been so oblivious to the tougher ethical scrutiny that younger members of Congress accept as a matter of course. “I tell my staff, ‘We dot every i and cross every t, and if we have any doubts, we get an advisory opinion from the ethics committee,’ ” said a Texas Democratic congressman and Wright loyalist. Another Democrat expressed astonishment that during the furor over Wright’s ethics a tempest sprang up over whether Wright’s staff had circumvented house procedures to let a Fort Worth contributor install a computer system in his office. “As a practical matter, you can help anybody but a contributor,” said the chief aide to another Texas Democrat. “When a contributor is involved you put everything in writing and run it by the ethics committee first.”

Apparently Wright thought otherwise in 1986, when he went to bat for Irving savings and loan owner Thomas Gaubert, who wanted help with the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. Like most Texas congressmen, in either party, Wright believed that federal regulators were treating Texas S&Ls too harshly; he wanted the regulators to give the institutions more time to work out their financial problems. To make his point Wright blocked a bill providing the board with funds to rescue failing S&Ls. Meanwhile, he sought federal forbearance for some Texas S&L owners. One was the soon-to-be-notorious Don Dixon of Vernon Savings and Loan. Another was Gaubert, a major donor to Wright and the national finance chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee at the time. Both now have civil fraud lawsuits pending against them. It is true, as Wright says, that he was only helping people who did business in his district, as every congressman does, and it is hard to imagine the ethics cornmittee punishing him for his involvement. Still, anyone who intervenes for a contributor at the same time he is throwing his weight around is inviting trouble.

Wright may not have appreciated the imperatives of modern politics, but his chief antagonist did. Newt Gingrich, a maverick Republican congressman from suburban Atlanta, has devoted much of the last year to the discomfiture of Jim Wright. Take the Aggie out of Phil Gramm—and the early career as a conservative Democrat—and what is left is Gingrich: a former college professor who is intelligent, partisan, ideological, and extreme in all three. Like Gramm, Gingrich is a master at using the media; also like Gramm, he is a gadfly who has little use for the gentlemanly traditions and comity of Congress. While Tip O’Neill was Speaker, Gingrich hit upon the idea of using the end-of-the-day speechmaking period, televised live on C-SPAN, as a forum for attacking Democrats in general and the Speaker in particular. Now Wright is his principal target.

Gingrich accelerated his campaign against Wright last September, when the Washington Post carried the details of Wright’s book-royalties arrangement, which earned him $55,600. The story didn’t stick, mainly because Gingrich is too far out of the mainstream to have credibility with the Washington press corps. For a time Wright successfully dismissed Gingrich’s attacks as pure partisanship.

The turning point came in May, when Common Cause, the nonpartisan citizens’ lobby, took up the call for an investigation of Wright by the House ethics committee. Common Cause legitimatized the story, and the hunt was on. Other revelations followed, minor but embarrassing nonetheless: Carlos Moore was a convicted felon (income tax evasion), Wright’s executive assistant also was a convicted felon (maiming), Wright had converted campaign funds to personal income in 1977 (allowed then but not now) but had chosen not to disclose it.

Not even Gingrich expects Wright to lose his case before the ethics committee, which has a notorious pussycat reputation. His official request for an investigation is carelessly drawn and is designed more for media consumption than for serious deliberation. Two of the four charges he submitted involve old oil investments made by Wright that Gingrich told the New York Times he had included “out of curiosity” and did not expect to be actionable. Gingrich’s other two charges focused on the book deal, but an author’s royalties are exempt from the House rule that members cannot receive excessive value for services.

Wright responded to Gingrich’s complaint with a letter to his colleagues containing a 23-page rebuttal of Gingrich’s charges. In an era when most politicians make official statements in the pablumized language of the press release, Wright’s defense is obviously his own handiwork. At times he emerges as a sympathetic figure, a man puzzled and saddened that anyone could doubt his integrity. “The solemn fact is that my net worth when I came to Congress at the age of 31 was considerably better by comparative terms than it is today when I am 65,” he wrote. “I am not complaining about that. I have been a fortunate man in that I have been permitted to do the thing that I most wanted to do. My goal—and just about my only professional goal in living at this point—is to be a good and effective public servant.”

But Wright’s explanation of the royalty arrangement is less persuasive. The 55 percent royalty did not violate the excessive income House rule, said Wright, because he received no advance. He noted that Tip O’Neill had received a reported $1 million advance for his book. Yes, but O’Neill’s book was a real book; his publisher was a real publisher, not a political crony; he was no longer in public office when the book came out; and his book was sold on the open market, not in bulk to lobbyists.

Wright’s defense may pass a legal test, but it doesn’t pass what politicians call the smell test. That is why the carelessness of Gingrich’s complaint doesn’t matter, but the carelessness of Wright’s approach to ethics does. Gingrich won as soon as the investigation of Wright became official.

The old witticism, “Aside from that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you enjoy the play?” must sound familiar to Jim Wright. Before being investigated by the ethics committee, Wright was enjoying a fruitful first term as Speaker. The House, which had functioned sluggishly in the late years of the O’Neill speakership, cranked out major bills addressing trade, highways, clean water, civil rights, housing, the homeless, and catastrophic health insurance. It overrode presidential vetoes of its first four bills. Wright gained national attention by getting involved in Nicaraguan peace talks. “The Republicans are after Jim Wright because he has been a very effective speaker,” says Democratic congressman Martin Frost of Dallas. “They could beat Tip O’Neill, but they can’t lay a glove on Wright legislatively.”

But success came at a price. Republicans say—and some Texas Democrats privately agree—that Wright has manipulated House rules to prevent them from airing their views. They complain that Wright’s legislative successes have been achieved only because he bypasses normal House procedures. Most of all, they are angry that Wright has contempt for Ronald Reagan and does nothing to disguise it. If the Republican attacks on Wright are motivated by partisan politics, Wright’s method of running the House has been no less partisan. As one Democratic congressman put it, “This is a case of what goes around comes around. He has made the Republicans hate him.”

The ill feeling is apparent every morning that the House is in session. The day’s work begins with the approval of the journal from the previous day. That used to be a routine motion approved without objection, unless the Republicans were angry about a perceived injustice that had occurred the day before. Now the Republicans object almost every day, forcing a time-consuming record vote as a protest against the way Jim Wright has turned House rules against them.

The Republicans’ chief complaint is that the Rules Committee, which is controlled by the Speaker, frequently spikes their only weapon—their ability to offer amendments. A minority party doesn’t have the votes to defeat a bill outright, but it can sometimes win enough allies to prevail on amendments. Even if the amendments fail, the minority can use them to force members to cast votes that might be unpopular back home—perhaps so unpopular that the minority can become the majority.

That is how the system worked until Ronald Reagan became president in 1981 and a coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats seized effective control of the House. When the Democrats regained absolute control in 1983, they began to limit amendments more often—to keep the 435-member House from bogging down, they said. To protect the majority from embarrassing votes, the Republicans countered. In the 1981–82 session, only 20 percent of the bills were debated under restrictive rules. Under Jim Wright, 44 percent of the bills have rules that limit amendments, up from 36 percent in O’Neill’s last session.

A restrictive rule denied the Republicans the right to offer a substitute to a contra aid bill—after, Republicans say, Wright had promised minority leader Bob Michel that they could do so. The Democrats are planning to use the rules to force Michel to offer a substitute when he doesn’t want to. A conservative bipartisan coalition opposed to a Democratic minimum-wage bill expects a rule that only the minority leader can offer an amendment—a ploy that puts coalition Democrats in the position of voting against their party if they support Michel’s amendment. “The entire process and procedure has become a deliberate tool to prevail on the substance,” says a Texas Republican congressman. “They believe that they have the right and obligation to structure rules to reach the outcome they want.”

The Republicans’ unhappiness over the rules is part of a larger frustration over the decline of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. For a time in the early eighties it seemed as if Republicans might take over the House. Instead they lost ground, returning to the status of a permanent opposition. It is not an enviable position; a freshman Democrat has more power and far more prospects than most senior Republicans. In place of Tip O’Neill, a Speaker who got along with the president and opposed him for reasons that were philosophical, the Republicans find Jim Wright, who doesn’t get along with the president and opposes him for reasons they are convinced are personal.

Like many successful Texas Democrats, Wright has never been fixable on the ideological spectrum. So it is easy for Republicans, ideological creatures themselves, to conclude that Wright is motivated primarily by an intense desire to beat a president whom he openly does not respect. Why else, they wonder, would he break the rules about how government should be conducted by negotiating directly with President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua and undercutting U.S. foreign policy? In all of their objections to the Speaker the Republicans may not be right, but they are certainly righteous. And they will be as hostile in their treatment of him as he has been in his treatment of them.

Wright would be better placed to deal with his enemies if he had more friends. As with his ethics, he has not handled his speakership in ways that would make him less vulnerable to attack. One of the themes Texas congressmen in both parties sound about Wright is that he is a loner. “You don’t chew the fat with Jim Wright,” says one Democrat. Before Wright was elected Speaker he talked about reopening the Capitol’s Board of Education room, where Sam Rayburn once held court every afternoon. It hasn’t happened. Wright is not part of the Washington establishment, nor does he cultivate it; its members, Bob Strauss excepted, have been conspicuously silent in his defense. Wright hasn’t cultivated the press either. His staff, composed mainly of people who have been with him for years, isn’t respected by other top aides. He has a renowned temper but no one to keep him out of trouble, a bad situation for someone who seems to be trouble-prone. Odd, isn’t it, that a person who hasn’t reflected enough about what it takes to be successful in Washington and who is very private would call his book Reflections of a Public Man?

Jim Wright is not a crook. He has not enriched himself in a career in public office. He has not committed any major breach of House rules, and unless a smoking gun emerges, he will continue to be Speaker of the House. It is even possible to view him as a victim—of partisanship, of journalistic scandalmongering, and of unwritten ethical standards that make much ado about very little. But that is not how Washington views him. He committed a human misdemeanor, but a political felony: he revealed himself as ordinary. He is exactly what his career indicates—a survivor, someone who moved up through the ranks by longevity, luck, and doing favors for his colleagues until the only person in line ahead of him, Tip O’Neill, retired. He will still have power, but in the future he will not have respect.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Scandal

- Longreads