There was, I think, a special quality of mercy to the Prince of Hamburgers drive-in on Lemmon Avenue in Dallas. It provided a certain consolation, with regard to one’s own doubts and physical prospects, in the cheerful incoherence of its structural accretions amid general deterioration over the decades. From benign dilapidation there emerged, like wine from an ancient, dusty bottle, something good. The burgers were good. And the root beer very good indeed, made on the spot, from rudimentary ingredients, or so I imagined as a child of seven or so when, having taken a booth inside with my mom and dad one winter night, I got to watch the precious distillate—ascended through a tangle of copper tubes from somewhere far below presumably—condense slowly, drop by drop, into a can.

It would occur to me years later, as I noticed what appeared to be a troublesome refrigeration system opened up beneath the counter for repairs, that what I’d been allowed to get down on my hands and knees to watch, enthralled, was probably a leaky pipe. Some dirty brown refrigerant, or who knows what, collecting. But not root beer. Not that essence of the goodness of the earth itself brought forth, refined, decanted doubly precious into frosty half-size mugs. Those kid-size mugs, of heavy, faceted glass just like the massive grown-up ones, encouraged, I am certain, a more thoughtful, concentrated appreciation of the contents. Thus one felt constrained to observe the marvelous properties of root beer as it foamed and steamed and formed upon the sides that icy slush that sloughed away like Arctic coastline into the mix beneath the clouds of one’s own breath. You didn’t think about all this, of course, but you took it in the way kids do: immediately and directly. Down the hatch. Eyes closed. A sigh. You wouldn’t think, at seven, a sigh could have such meaning. Yet I feel it now and feel I must have felt the meaning then.

The Prince of Hamburgers seemed to constitute its own conceptual precinct—like Vatican City on a somewhat smaller scale. It had this ten- or twelve-foot white board fence around it. Had developed, over years and years, an emotional jurisdiction of its own. The pure-white-stuccoed, curvy-cornered, flat-roofed, vaguely Bauhaus modernism must have been quite striking back in 1927, when it opened. Lemmon Avenue then was an unpaved road extending toward the prairie. You imagine people heading out to the very edge of nowhere, as it must have seemed—as my mom in fact described it, having gone there with her father once or twice—to have a burger and a root beer in the future. You imagine that’s how people would have thought of it in 1927. Such a kindness, at the edge of things like that, before the crash, before the Dust Bowl and the next world war, to find a sense of future and a sense of comfort in it.

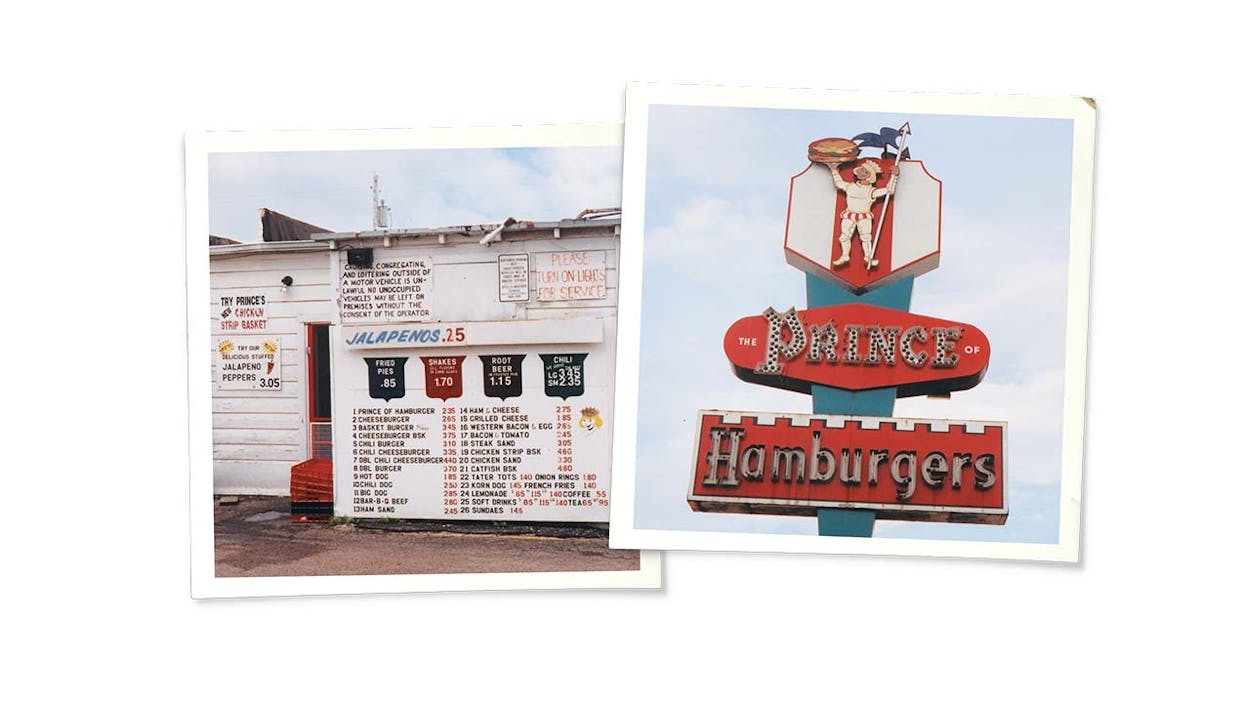

By the time I took my first kid’s mug of root beer in the fifties, though, the futuristic moment there within the white-fenced precinct had deteriorated, complicated by doubt and practicality—an odd wood-frame extension off the back to make this zigzag-entranced restroom; picket fencing for the outside storage areas; a plywood, shingle-roofed enclosure for the carhops. All preserved beneath innumerable layers of palliative, almost bandagelike white paint. It covered all the cracks and splinterings and uncertainties. The spallings of the stucco, the mistakes and imperfections. And suggested it was all okay. The whole discordant thing. With red-and-white-striped carnival awnings over the parking. And out front, so peculiar against the modernistic entrance, this huge neon and incandescent sign, medieval-themed, like heraldry—your battlements, your pseudo-gothic font, your pennant dangling from a shield, and there atop it all, transcending inconsistency, the golden-pageboyed Prince himself, his mighty lance in one hand, giant burger in the other. There was nothing more to say. You had it all. The past and future intermingled, reconciled, and averaged into a sort of calm, a sort of neither-here-nor-thereness, a release from the rush, the thoroughfare of Laundromats and liquor stores that Lemmon Avenue had become by the fifties. You pulled off into an accidental eddy in the current and, weather permitting, parked beneath the luffing awning, flashed your lights, and here they came: the lovely ladies. Older, younger, lipsticked smiles as they approached (I like to imagine in slow motion) across the asphalt to receive into the little pale green book of sales receipts one’s application for a burger and a root beer. Well, we’ll have to see. You never know. Can something good emerge from the confusion of the world? But, sure enough, it always did. Like grace out of that sweet ambivalence. And all the sweeter for it.

I remember how, at night, when we pulled in, our headlights shown across that white board fence to make us feel admitted and contained. Forgiven, even, had I homework, hateful multiplication tables, still to do—look how the white paint covered everything. The knots and splits in the fence. Held back the night beyond the fence, as it seemed to me. There might be anything out there. All sorts of failure and anxiety. All sorts of obligation. People lived and died out there. But here we waited under the lights, beneath the awning, in our car in such a clear suspended state of expectation that it seemed to last forever. Which was wonderful to me. The prolongation due, no doubt, to the time it took the marvelous distillate to gather into a kid-size mug. You held it in both hands and took it in and breathed into it. Felt the sweetness of the darkness of the liquid as a sort of concentration of the whiteness of the moment.

Toward the end, around the turn of the millennium, it was possible to detect an instability of some sort. There was only so much that white paint could address. I’d stop by now and then in the evenings for an order to go, for me and the kids (the root beer wasn’t quite the same in a paper cup). And there the owner or lessee or whatever he was would be sitting in the corner booth with the day’s receipts—the tickets and the cash, these piles of cash—and a calculator. A sense of urgency. As if in the face of some approaching peril. One imagined a revolver in his belt. The white board fence had vanished not too long before. And I began to notice, also, with what curious regularity the jukebox got changed out. No reason for it that I could tell. It didn’t seem to be a matter of selection or technology. The same old songs. The load of sentiment pretty much the same were it a Seeburg or Rock-Ola or whatever. It seemed rather like the sad, increasing need to change the oxygen tanks supplying some poor invalid. And then in spring 2005, the place got shut down. Locked up. They had not been paying sales tax for a while, it was reported. How bizarre. More likely someone just neglected to change the jukebox. And by summer it was clearly gone for good, the sign and awnings hauled away. By a collector, I was told. In its reduction on that empty lot, the little stucco building felt returned to the edge of nowhere. To that faint, precarious futuristic notion. But it was starting to come apart. Debris was scattered here and there. The carhop shed was boarded up.

I’d drive by now and then. Not stopping, just to note the rate at which this thing—which I had come to regard as an idea, an understanding—fell apart. Like when a dead whale washes up somewhere. We all love whales. We sort of want to see it. But we don’t want to see too much, you know, at last.

Yet this particular summer day I make a U-turn, slow, pull in. Get out. The front door, stripped of its art deco-ish hardware, is wide open. Very dark in there at noon. The sun straight overhead. I walk in out of the glare and can’t see much at first. Except that it’s been trashed and emptied out. Were it back there at the edge of things in 1927, you would probably hear the insects in the fields. The sound of traffic is sort of like that now, it occurs to me. The past and future still confused a bit.

And here—it takes a couple of seconds as my eyes adjust—just watching me from over by the counter is a very curious figure. He is shadowy—tanned that gritty, dusty tan that does not speak of recreation—and quite small, about five-four, I’d guess. And homeless, he will tell me. Discontented, I will come to understand. Half-blind (although I see him lift the eye patch and squint, so maybe not quite half), and drinking one of those giant cans of beer in a paper sack. He’ll have me know he knows the owners, and they’ve hired him to keep an eye on things. I think those are his words—without a smile. He doesn’t smile. But if there’s anything I want, he is empowered to collect a little money for it. Sure. Of course. Makes sense. No problem there.

I poke around, then go outside. He tags along. He has complaints—his health, the world. The world impinging and in general. The sun stands still. Straight up. No shadows out here on the lot. The gentle buzzing of the traffic. He seems darker. Even smaller, even sadder in the sunlight. His complaints more concentrated and more volatile. We need to go back in and strike a bargain. I have gathered what I need. I think I know who I am dealing with. He couldn’t be more opposite the happy golden Prince. He is the flip side. Alter ego. The embodiment of failure and anxiety. The dark beyond the fence. He has his beer now, seems at ease. He is the one, I’m pretty sure, who comes around when you are bad. When you neglect to do your homework, pay your taxes. When great empires grow complacent in the broad historical moment, he presides at the destruction. There is nothing to be done. We reach a deal at thirty bucks and I depart.

So, what I have here—what it all comes down to, finally—is a nasty-looking carving knife with a broken wooden handle and an even nastier cleaver blade with chunks out of the edge, like something taken from the evidence room; a gimme cap with the Prince and a burger on it; a rubber stamp with the company name and address; and a stationary cast-iron bottle opener (very possibly from when I was a kid—I found a book on these that dates this one from 1943 to 1975). And, from the carhop station, right there by the door to the parking lot where they, the carhops, beautiful women all, such angels, would be waiting to come out to us, a little dime-store mirror with a perfect lipstick kiss at the lower left.

Dallas writer David Searcy is the author of the recent essay collection Shame and Wonder.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Dallas