The first person I think of when it comes to cooking like a Texan is Enrique Madrid. You probably have someone you think of, your father, perhaps, or your grandmother. I think of Enrique, a historian, archaeologist, cook, defender of the borderlands, author, and lecturer whose family has been living in the area around what is now Redford for about 12,000 years. If you’ve spent much time in Redford, which not many people have, you’ve likely encountered Enrique, or at one point maybe you encountered his father or his mother, a schoolteacher who was awarded two presidential medals by George H.W. Bush for, among other things, building her own very good public library in the middle of the desert, book by book.

The Madrid house is a modest, rambling place alongside FM 170 not far from Big Bend National Park. In addition to the library, it once housed a general store and gas station, run by Enrique’s father, and since 1975 it has served as a kind of classroom where Enrique has performed God knows how many demonstrations of Mexican cookery for curious visitors. He is a generous teacher, capable of demonstrating a great many techniques related to the local cuisine, from goat slaughter to cactus harvesting, but his stock-in-trade is the refried beans demo and the tortilla equation.

I met Enrique twelve years ago. After we got to know each other, he invited me over for the bean demo. “You know how the Eskimos have thirty words for snow?” he said, as he tended the boiling beans. “We have as many words for the different stages of the beans. One of them is when you throw them into the smoking-hot lard. That’s called guisar. There’s really no good English translation for guisar. The best is probably ‘explosion-frying.’ The beans aren’t going to be good unless the smoke hits the ceiling in an atomic cloud. Eventually your kitchen ceiling gets all grody-looking.”

He dropped some beans into the pan, and a giant plume shot up to the ceiling. As it cleared I noticed a stain where it had hit, a dark residue from decades of meals. “My mission is to save endangered flavors,” he said, over the roar of the frying. “Once we forget how to create them, they’re really gone forever. So I try to teach people how to cook the way my grandmother would.”

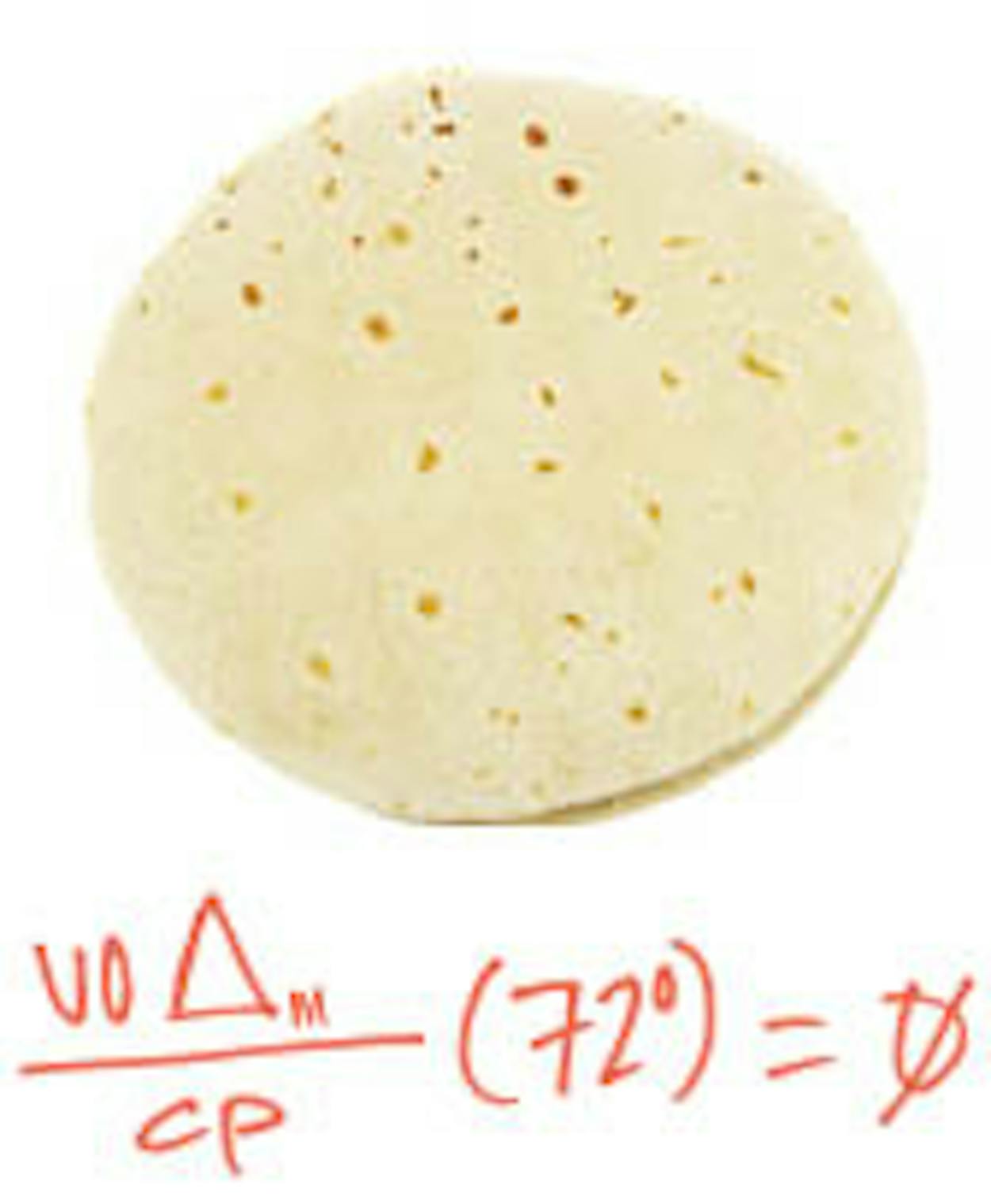

The tortilla equation is a different story. It came about when Enrique was down in Chihuahua, interviewing women about cooking techniques. Impressed by the fact that they all made perfectly round tortillas, he started thinking about the mathematical laws of the universe, and he came up with his equation (above), which, to my way of thinking, deserves to be taught, at least in Texas, right alongside the Pythagorean theorem.

The numerator uoΔm stands for the uniform omnidirectional distribution of mass (when explaining the equation, Enrique likes to point out that “mass” in Spanish is masa, which means “dough”); the denominator CP stands for the central plane of a sphere; 72º accounts for the degrees of rotation made while rolling the tortilla flat; and Ø represents a perfectly round tortilla. Talking about the variables tends to bring out Enrique’s mystical side: “uoΔm also describes the first nano-instance of the expansion from a singularity in the big bang,” he once told me.

There are no other mathematical equations in this issue’s package on how to prepare essential Texas foods (though there must be a brisket algorithm; if you discover it, please let me know), but there is an inspiring group of people who feel just as passionately about their food as Enrique does about his. For these people, as for all of us, the ten dishes in this issue amount to a cultural heritage, as treasured as literature or music, by which we commune daily and weekly with this place we call home.

The meaning of food, of course, is never limited to its nutritional content alone. As Enrique told me, that first night around his kitchen table, as we dug into a (delicious) meal of beans, tortillas, and chiles rellenos, “There’s an important moral lesson here: If you want to hurt people or to kill people, you take away their food. So we have to feed people. Sharing food is the most important human relationship there is. The more we eat the same foods, the more we can trust each other.”

Next Month

The building of a baseball dynasty in Arlington; the birdwatcher who turned George W. Bush on to birdwatching; a roundtable discussion on the funding crisis in public education; the strange story of the East Texas church arsonists; and an exclusive excerpt from Stephen Harrigan’s new novel, Remember Ben Clayton.