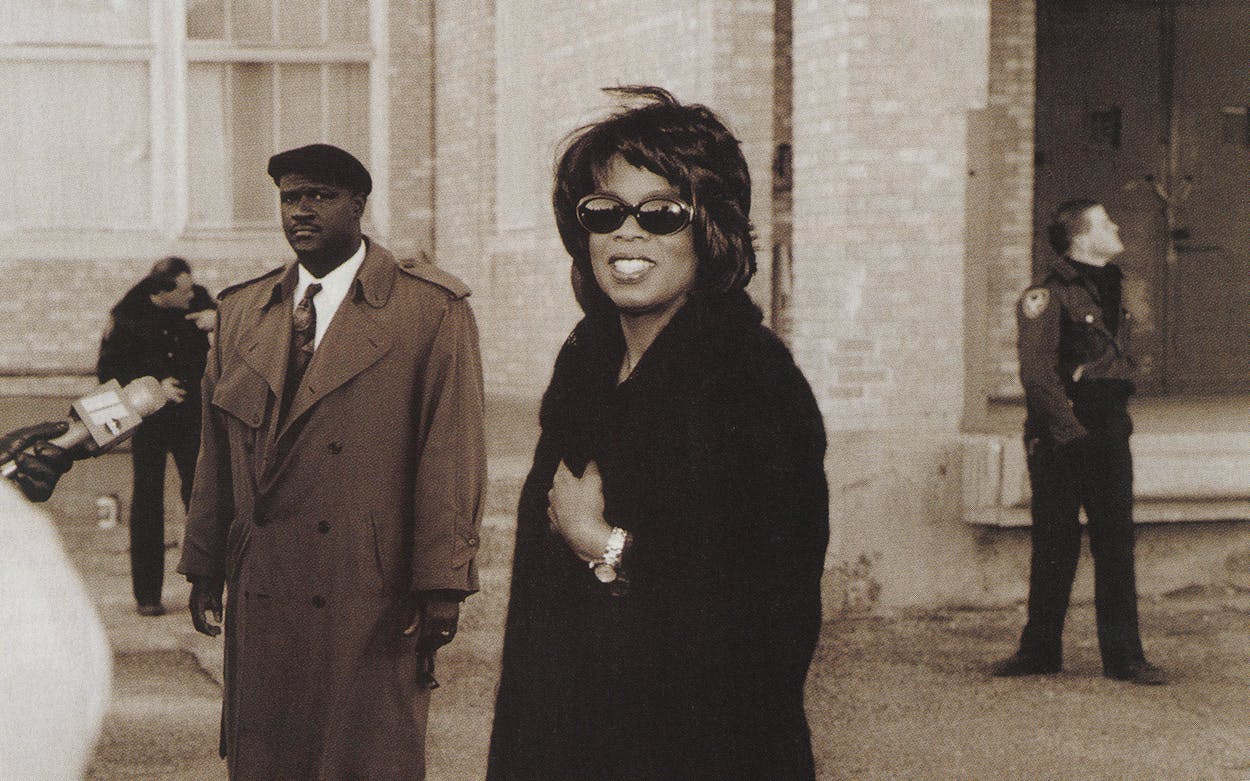

As she stepped from her from her Gulfstream jet, her two small cocker spaniels, Solomon and Sheba, nestled in her arms, Oprah Winfrey stopped for a moment and stared in silence at the treeless Panhandle horizon. She seemed stunned at what lay before her.

“Oprah!” shouted members of the news media from a roped-off area fifty yards away. From that distance, she looked like a great religious figure, her flowing brown pantsuit billowing in the wind like the robes of a prophet. The three local television stations cut into their regular programming to broadcast her arrival. “Oprah, how do you feel?” one of the reporters called out.

She hesitated for another moment, still staring at the unbroken flatness, and then turned to the cameras and offered her most cheerful wave. Escorted by bodyguards, she slipped into a black Chevrolet Suburban with black tinted windows, which raced her off to a meeting with her attorneys. “She’s here!” an ecstatic Amarillo television reporter shouted into his microphone. “Oprah is here in Amarillo, and she has just waved right at us!”

Just when you thought that Texas was no longer Texas, just when you thought that we were finally becoming just like everyone else, something like the Oprah trial comes along. Who could have guessed that one of the most obscure and embarrassingly titled state laws on record—the False Disparagement of Perishable Food Products Act—would set off the most uproarious Texas range war since the fight over barbed wire? And, oh, what a glorious war, waged by a group of rich Texas cattle barons, the classic symbols of old frontier Texas, against an even richer black Chicago talk-show hostess, a classic symbol of modern-day American success. In ways that no one could have expected, the Oprah trial, involving a $12 million disparagement lawsuit over her April 1996 show about mad cow disease, became a battle for the heart and soul of the state. The cattle barons who filed the lawsuit saw themselves as Alamo-like defenders, hoping to save Texas from this contemporary Santa Anna who dared to say that she would never eat another hamburger. Winfrey, in turn, decided to counterattack with her best weapon: her own celebrity. She planned on turning Amarillo, the sagebrush kingdom, into Oprahrillo, broadcasting her daily show from the city during the trial’s duration and even changing the show’s name to Oprah Winfrey in Texas. “She’s going to do her best to charm our pants off, and we all know she’s good at it,” grumbled Charles Rittenberry, a popular Amarillo trial lawyer, just before the trial began. “I don’t know if our local cowboys are going to come out on top of this damn deal. We’ve already got wives of respectable ranchers sneaking around town, trying to get tickets to Oprah’s show. I’m telling you, Oprah’s about to cause a lot of hell to break loose out here.”

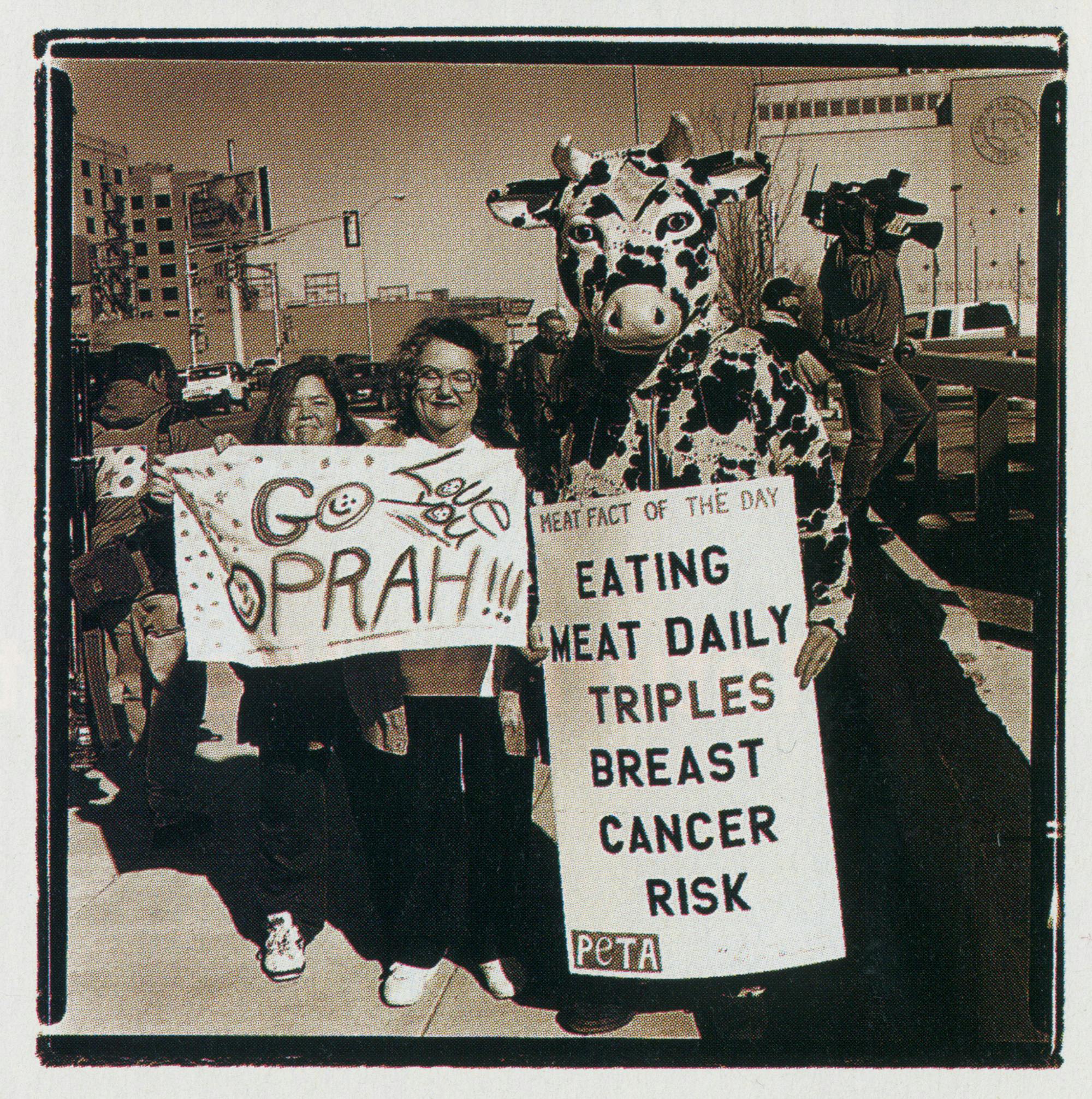

Indeed, the Oprah trial was about to bring together an array of down-home West Texans and East Coast—educated lawyers, solemn New York Times reporters and bubbly Entertainment Tonight correspondents, bombastic vegetarian protesters, courthouse demonstrators wearing cow costumes, and even a marching kazoo band that stood outside the courthouse one bone-chilling winter day to play the Andy Griffith Show theme song, allegedly Winfrey’s favorite tune. “We’re all getting Oprah-itis; I can feel it in my bones,” said Amarillo’s famous millionaire eccentric, Stanley Marsh 3, the owner of a local television station and the creator of the display of half-buried cadillacs known as Cadillac Ranch. “By the time this thing is over, Texas is never going to be the same.”

EXCERPTS FROM THE OPRAH MAD COW EPISODE have been rerun so many times that even people who don’t watch daytime TV know them by heart. Howard Lyman, a failed Montana rancher turned vegetarian and animal rights activist, told Winfrey that American cattle were being fed ground-up meal made from dead livestock—the same practice that might have caused the spread of mad cow disease in Britain. (“Mad cow disease” is a brain-ravaging malady that has devastated cattle herds in Britain; in 1996 the British government announced that some humans may have died from eating beef contaminated by the disease.) Lyman argued that if the remains of one mad cow were fed to other cattle, thousands of cows, and in turn, countless American beefeaters, could be infected. As if on cue, Winfrey inquired, “You said this disease could make AIDS look like the common cold?” “Absolutely,” Lyman replied, leading Winfrey to declare, “It has just stopped me cold from eating another burger!”

Cattle breeders are accustomed to beating back such elements as drought, dust storms, locusts, and twisters to get their cattle to market. But in the words of 71-year-old Bourdon R. Barfield, a descendant of a pioneer family in Amarillo, “Oprah was bigger than any whirlwind.” On April 16, the very day her mad cow show aired, cattle futures prices on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange plunged. “Cattle prices had already been slipping somewhat,” said Teel Bivins, an Amarillo state senator and veteran rancher, “but Oprah’s show created a panic. The cattle market basically went into a free-fall.” One Texas A&M economist said that in the three weeks following the Oprah show the cattle-feeding industry lost $87.6 million, although other observers blamed the loss on a devastating drought and an already volatile market shaken by Britain’s mad cow scare.

Many of the nation’s cattlemen—who with their vast ranches, cattle drives, and roundups had created some of the most enduring images of American mythology—felt whupped by a talkative “city woman.” It wasn’t, however, the fairest of fights. The show’s producers cut out all but a few statements from a beef industry spokesman and a U.S. Agriculture Department expert on mad cow disease, both of whom insisted that American beef was safe. One of the show’s producers later admitted that Winfrey had told an editor to “cut out the boring beef guy.” Although she argued that she simply wanted to know why some cattle feeders were feeding cattle to cattle, her show did come off as rather alarmist. The reality was that the cattle industry had been moving away from such feed practices. And there had never been a documented case of mad cow disease in the U.S.

The cattlemen wanted revenge. But which of them dared to take on Oprah, the highest-paid entertainer in the world, once described on the cover of Life as “America’s most powerful woman”?

Enter Paul Engler, a native Nebraskan who had moved to the Panhandle in 1960 with one simple, albeit unglamorous, vision: to make cows fatter, faster. He envisioned fenced-in commercial feedlots stretching across the Panhandle where cattle would while away their last days by the feed trough. The notion eventually made him a multimillionaire and one of the most powerful cattlemen in the country. The 68-year-old Engler is all-male, as tough as a fence post; a framed photo of a double-barreled shotgun, permanently cocked at visitors, hangs over his desk. He’s known as a bit of a hellion; he once got so furious upon hearing himself called a farmer on television that he told his attorney, “If that guy calls me a farmer again, you sue his ass.”

“Engler could be one of John Wayne’s pals,” said Stanley Marsh. “He shakes your hand real hard, and for kicks, he’ll take you way up in the air in his helicopter and show you this real pretty lake on his property that looks yellow in the sunlight. When the helicopter gets lower, you realize it’s a lake of cow piss coming from his feedlots.”

Engler and three smaller Amarillo cattle feeders filed suit in federal court under the False Disparagement of Perishable Food Products Act, a 1995 law that states that those who interfere with the sale of Texas produce by knowingly making false statements can be held liable to the producer for damages. The lawsuit seemed flimsy at best. Winfrey’s announcement that she was swearing off beef was clearly protected by the First Amendment. And even if the show was flagrantly biased against cattlemen, at least some airtime had been given to the beef proponents. Furthermore, it was going to be difficult to pin the cattlemen’s financial losses (Engler said he had lost $6.7 million) directly on Winfrey, since beef prices had already been declining. And then there was the question of whether a law designed to protect perishable produce could be applied to livestock. “It’s questionable just how perishable a thousand-pound steer really is,” quipped Winfrey’s attorney, Chip Babcock of Dallas.

Standing in one of his wind-whipped feedlots last December, Engler said indignantly from beneath the brim of his white Stetson, “The picture presented on that show was that people in the beef industry were picking up dead cows in the middle of the night, tossing them in the back of their pickups, slicing them up, and then dumping bloody cow parts into feed troughs.” His cattle stood quietly in the mud, blinking slowly under their long lashes and chewing their feed. “Exaggerations, untruths, and innuendo,” he bellowed, flashing his thick gold ring emblazoned with a C of diamonds in honor of his company, Cactus Feeders. At the time, his desk was littered with fan letters and checks from ranchers from all over the country. Politicians also got into the act: The state’s agriculture commissioner, Rick Perry, told Engler to “go over and blow the hell out of them.” Engler knew that if he won his lawsuit, he would be considered one of the greatest cattlemen in Texas history, next to Charles Goodnight. “Let’s face it, some of the best days of Amarillo’s cowboy life are long gone,” said Charles Rittenberry, “so here was our chance for one last hurrah.”

Many lawyers figured the case would never get to trial, but late last year federal judge Mary Lou Robinson ruled the suit was valid, and then she shocked Winfrey’s attorneys by announcing that an impartial jury could be seated in Amarillo. The irony seemed too delicious to be true. Oprah was going to be forced to spend at least a month in Amarillo, the board game—flat beef capital of Texas—a city that has been known to smell like a cow patty when the wind comes out of the east and wafts through the stockyards on its way downtown. Yeehaw! Amarillo! The shoot-out was on.

BY THE TIME MOST OF THE NEWS media began showing up in Amarillo in late January for the trial, the city of 175,000 was close to pandemonium. “My God, everybody’s trying to figure out how to get on the jury,” said a local attorney. “I’ve even heard there are some women wanting to get on the jury just so they can pose nude for Playboy the way that O. J. Simpson juror did.”

During the first week of the trial, a dozen satellite television trucks circled the federal courthouse like a bunch of covered wagons, while national reporters fanned out through the city, looking for cowboys and rednecks and steak eaters. The coverage, of course, was not flattering. An Amarillo columnist said the national media had made Amarillo look like “a tumbleweed-strewn nest of yokels.” Kent Harrell, the news director of Amarillo television station KVII, was asked by the producer of a call-in radio talk show in New York whether there was a reporter at the station with a thick Texas drawl who could talk in a rustic way about the upcoming trial. Harrell said he had no such reporters: “We speak regular English out here.”

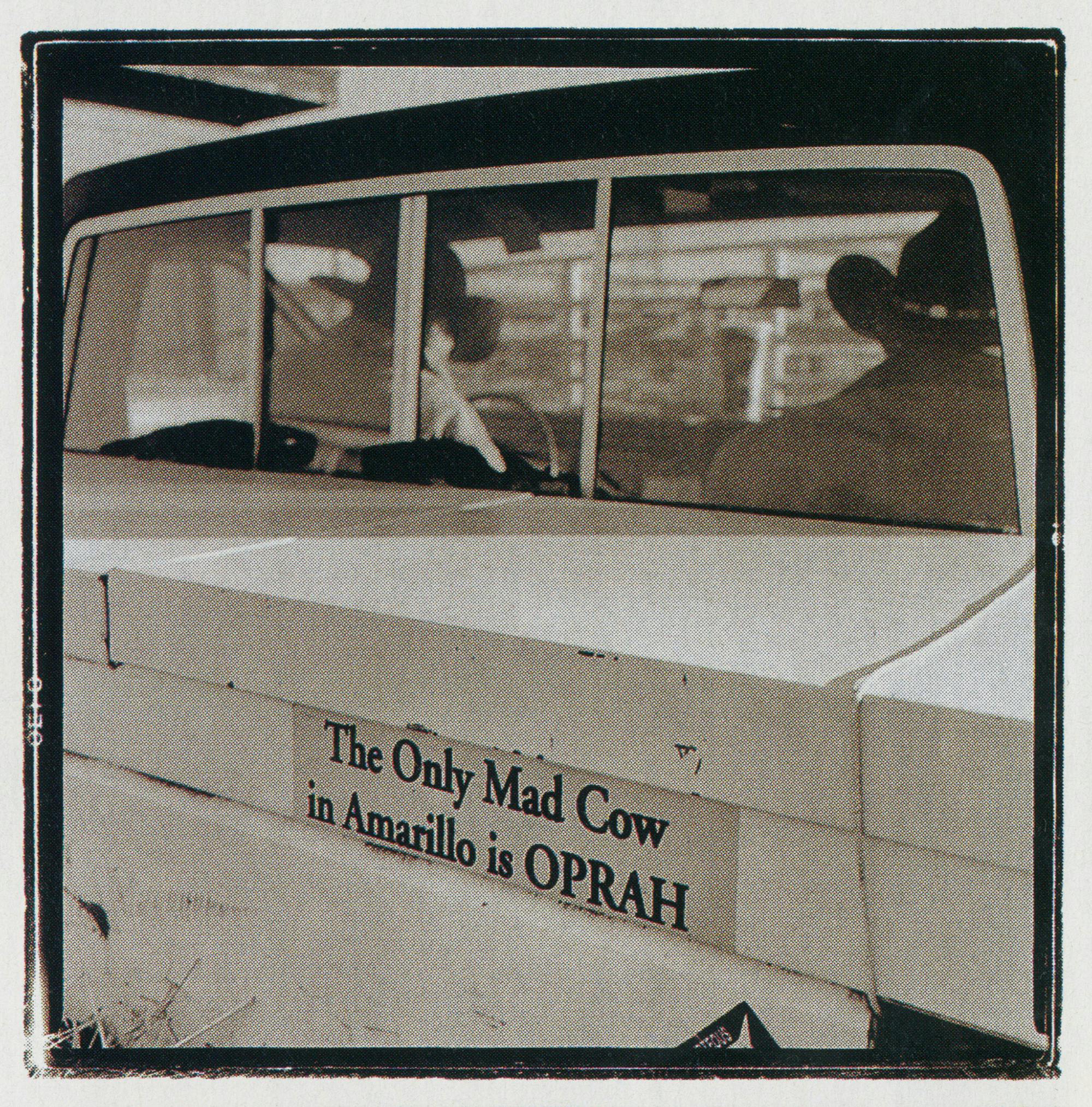

It was hard to believe that something or someone could interfere with Amarillo’s allegiance to beef. This, after all, is a city the cattlemen built. The lobby of the federal courthouse, where Winfrey would be put on trial, is ringed with a sweeping mural of a cattle drive. Amarillo’s largest private employer, with 3,300 workers, is the Iowa Beef Processors’ slaughterhouse. One of the city’s most famous landmarks is the Big Texan Steak Ranch, which offers a 72-ounce steak (four and a half pounds) free if a customer can eat it and all the trimmings in an hour. Within 150 miles of Amarillo, six million head of cattle, a third of the nation’s cattle supply, are fattened in feedlots. All of which would explain those fire-red bumper stickers proclaiming “The Only Mad Cow in Amarillo is OPRAH” that dotted the city. To show his support for Panhandle cattlemen, Gary Molberg, Amarillo’s chamber of commerce president, issued an internal memo in early January admonishing the chamber’s staff not to attend Winfrey’s show while it was broadcasting in Amarillo nor to give her or her production company “any red carpet rollouts, key to the city, flowers.”

But then came a major defection from the ranks of Amarillo’s power structure. Nancy Seliger, the spunky wife of Amarillo mayor Kel Seliger, sent Winfrey a handwritten note inviting her to a meeting of Seliger’s book club. Every woman in Amarillo knew within days what happened next: Winfrey immediately picked up the phone, called Mrs. Seliger, graciously thanked her, and chatted with her for several minutes about—among other things—where to get her hair done in Amarillo.

Although Engler was no longer talking to the press—the judge had slapped a gag order on all potential witnesses and lawyers involved in the case—the word was that he and his cohorts were dismayed that one of Amarillo’s finer women would cross the line. (“We are proud of the town our cattlemen built,” said Nancy Seliger, “but there was no sense in being rude.”) One can only guess how Engler reacted when phone lines across the Panhandle temporarily shut down one afternoon after an 800-number advertising tickets to tapings of Oprah in Amarillo flashed across television screens. A spokesman for the show said 215,000 calls came in within thirty minutes.

What had happened? Instead of creating a ground swell of support for cattlemen, the industry’s practices were being scrutinized more closely than ever by the media. Ralph Nader wrote a column, printed in newspapers around the country, comparing the cattlemen’s suit with King George III’s attempts to silence Americans. Other writers said that Engler’s lawsuit threatened the First Amendment. The Dallas Morning News received letters calling Engler and his supporters “crybaby cattlemen” and “spoiled children.”

“People in the beef industry,” said one insider, “are saying off the record that this is a public relations disaster.” In an early survey the Amarillo Globe-News found that 1,284 of its responding readers thought Winfrey would win, while only 280 thought the cattleman would. Agriculture commissioner Perry, a gung ho backer of the lawsuit, was conspicuously quiet about it—maybe because he was running for lieutenant governor. By mid-January, the fire-red bumper stickers seemed to have thinned out, outnumbered by “Amarillo Loves Oprah” T-shirts. When Gary Molberg, the hapless chamber of commerce president, realized just what support there was for Winfrey in Amarillo—some residents were lining up alongside a remote highway before dawn in the bitter cold simply to watch her jog—he issued a retraction of his memo and sent her a bouquet of yellow roses.

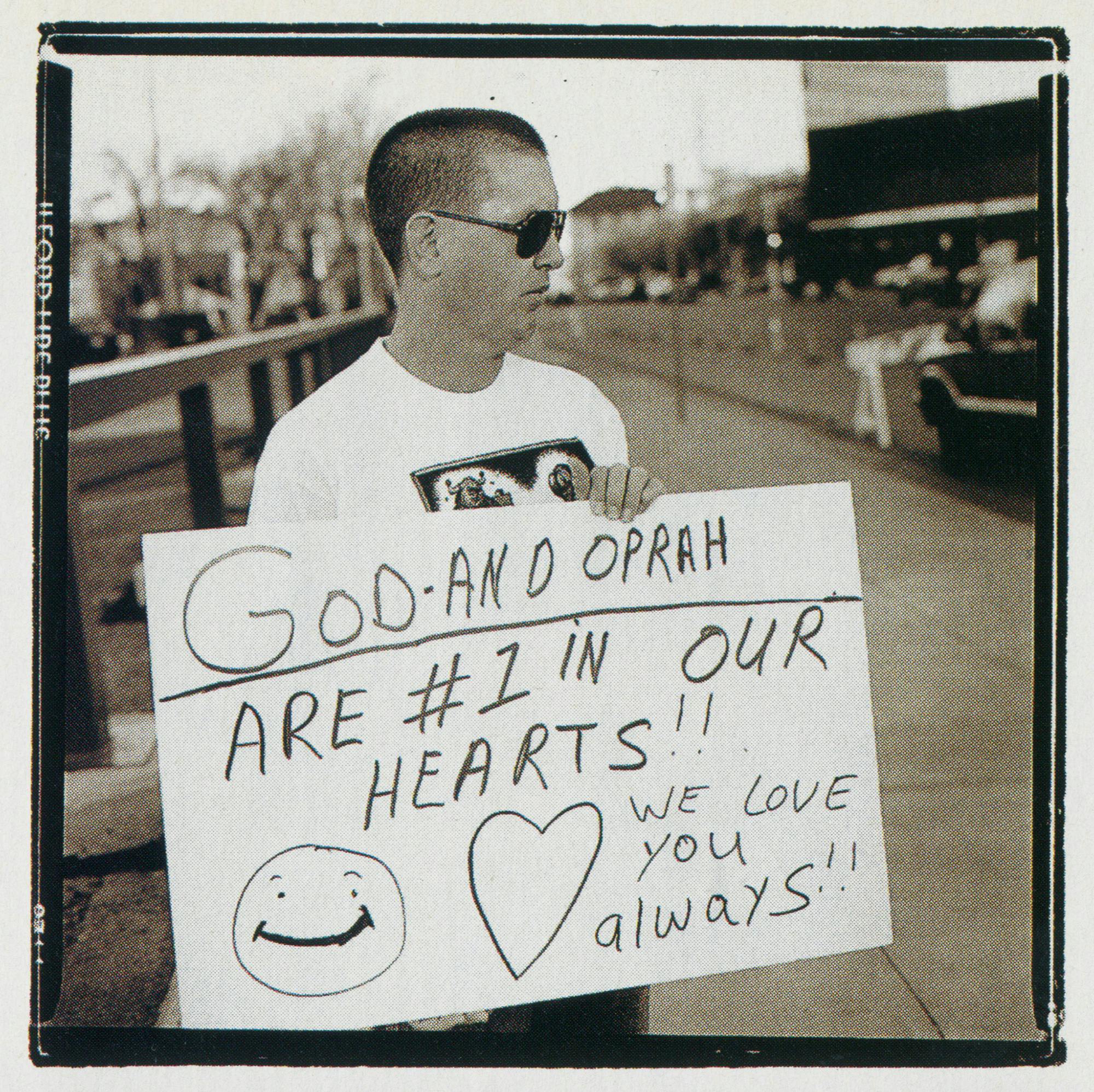

Not that she needed him. The first week of the trial made it clear that there were a lot of Amarillans who worshiped Oprah. Every morning, just for her benefit, one local television station reported the temperature in Chicago, while another offered a daily sight-seeing tip just for her. One television reporter gave a sincere look at the camera and said, “Oprah, if you’re watching, please come down to the station, and we’ll talk about anything you wish!” Almost every morning when she arrived at the courthouse in her black Suburban, a throng of female fans raced down the sidewalk to get a better look at her. “We love you, Oprah!” they screamed. “We love you!” Winfrey was forbidden to speak about the suit, but she knew how to get attention. When she left at the end of the day, she always rolled down the window of the car, stuck her head out, and smiled benevolently at everyone. When her getaway was halted at one point by an inopportune red light, fans stormed the street, mobbing the car. “Jesus, you’d think it was the president and his intern in there,” one Amarillo cop muttered to another by the barricades.

Other than reporters, few spectators even recognized Engler as he strode in and out of the courthouse. One afternoon the great cattleman, known in the industry as the Father of the Feedlots, found himself walking past 150 people who had gathered to serenade Winfrey with kazoos. A chagrined Engler slouched under his Stetson, crossed Taylor Street, and disappeared around the next corner as the kazoos buzzed merrily behind him. The sole vocal demonstrator for Engler’s group was a rather obnoxious man who, over the din, frantically shouted, “Eat more beef!” “I have no doubt that Engler thought he was walking into a hometown court and putting a foreigner on trial,” said Jeff Blackburn, an Amarillo attorney who had been used by CNN as an expert commentator on the Oprah trial. “To these cattlemen, Oprah—a successful black woman from Chicago—seems like a foreigner. But the real comeuppance is that Engler is a lot more foreign to people here than Oprah. People in Amarillo watch Oprah every day.”

And to keep everyone watching, Winfrey made sure that her shows, taped at the Amarillo Little Theatre, were filled with extravagant salutes to the very place she was being accused of ruining. “Get ready for Oprah, Texas-style!” the announcer would say at the beginning of each show, and from behind the curtain would come Oprah, grinning like a rodeo queen. Her first show included two native Texans, country music singer Clint Black and movie star Patrick Swayze, who gave her a cowboy hat and a pair of black Lucchese boots and then two-stepped with her around the stage. There were pre-taped clips of Texas celebrities, such as LeAnn Rimes and Kenny Rogers, welcoming Oprah to Texas. Other shows celebrated all things big in Texas, including gigantic mansions, huge ranches, big hair, big purses, and multimillionaire bachelors who were looking for that perfect gal. Winfrey loved talking with a fake countrified Texas accent, using phrases such as “How are y’all?” and “Did you now?” and “That’s where the rubber hits the road, I reckon.” At some point in every show she would mention how nice she found the people of Amarillo. Under the colored lights, at the lip of the stage, they beamed back at her.

DESPITE THE BEDLAM OUTSIDE THE COURTROOM, there was still a decent possibility that Engler and his fellow cattlemen could win inside. The all-white jury included a woman who had been involved in cattle feeding 25 years ago and a descendant of one of Amarillo’s oldest ranching families. The jurors sat through laborious testimony—involving carcass weights, commodities markets, and the difference between feeder cattle and fed cattle—as many spectators nodded off. When Engler’s son mixed up a bunch of cattle feed in a barrel before the jury, Winfrey looked nauseated. Otherwise, she did an admirable job of looking interested, scribbling notes on her legal pad and listening intently to discussions about slaughterhouse quotas and the “scrapie control program.”

Engler’s attorneys put up a good fight, proving that he had long ago stopped using ground-up meat meal at his feedlots and showing how slipshod the editing of the mad cow episode had been. There was testimony from the beef expert whom Winfrey had told after the first show, “We weren’t fair to you,” and from a government expert on mad cow disease who said there was “a snowball’s chance in hell” that mad cow disease would ever strike the U.S. Later he broke down in tears as he recalled his attempts to defend beef on the show, describing the perky female audience as a “lynch mob.”

Then, midway through the third week of the trial, as a cold, thick fog rolled in over the city, it was Winfrey’s turn to talk. She ascended the courthouse stairs among a cluster of U.S. marshals, clutching the hand of her close friend, poet Maya Angelou. Outside the courthouse, her fans—including a man in a cow suit and a woman holding a sign that read “U Are Loved”—held a silent vigil in the below-freezing temperatures. Inside, after Angelou whispered some encouraging words in her ear, Winfrey rose slowly from her seat and walked to the witness stand. Spectators in the packed courtroom sucked in their breath. The moment of truth had arrived.

Engler’s persistent attorney, Joseph Coyne, began by taking her through the entire transcript of the show, line by excruciating line, slowly picking apart each word. He pointedly asked about her decision to swear off beef and grilled her about her show’s anti-beef agenda. Winfrey’s patience with Coyne quickly wore thin: She sighed loudly, restlessly tossed her black hair over her shoulder, and cast sidelong glances at her legal team. But Coyne bore in, accusing her of negligence for not double-checking Howard Lyman’s claims or remedying her producer’s careless editing. After one particularly insistent line of repetitive questioning, Winfrey paused, peered at the lawyer, leaned in to the microphone, and in a thrilling, low voice, thundered: “Mr. Coyne, I provide a forum for people to express their opinions . . . This is the United States of America. We are allowed to do this in the United States of America.” It was as if an electric current suddenly ran through the courtroom. Spectators who had slouched for hours on the court’s hardwood benches suddenly straightened up, craning to get a better view of the witness box. Reporters scribbled in their notepads while the cattlemen’s wives nudged each other anxiously.

By the time Winfrey’s attorney took the floor, the talk-show queen’s tone had taken on the air of a revival-meeting sermon. “I am a black woman in America, having gotten here believing in a power greater than myself,” she intoned in response to a question about her integrity. “I cannot be bought. I answer to the spirit of God that lives in us all.” She recounted her penniless beginnings in backwater Mississippi and her hardscrabble rise to fame, which began with her winning first place in Nashville’s Miss Fire Prevention contest when she was seventeen. As spectators hung on her every word, she chronicled her triumphs over childhood abuse, racism, obesity, and poverty to become one of the wealthiest, most influential women in the world. Paul Engler shifted uneasily in his chair. Was it possible that he and his fellow plaintiffs were thinking—as others in the courtroom certainly were—that this black urban woman embodied all the rugged, heroic qualities that we used to look for in the great Texas men of the past, men who had tamed the vast frontier? Men who believed they could accomplish anything? Men who didn’t need lawyers to help them earn a living? Winfrey turned and looked directly at the twelve jurors who were soon to judge her. “I am in this courtroom to defend my name,” she said. “I feel in my heart I’ve never done a malicious act against any human being.”

THERE WERE STILL PLENTY OF OTHER WITNESSES to be heard—the trial was expected to last through the end of February—but many Amarillo lawyers who had been following the case figured Engler was sunk. No one around town appeared particularly upset. The cattlemen were still making money. People were still eating beef. And the citizens had other things to think about, namely getting home early from work so they could catch Oprah’s show. Every night the Amarillo Little Theatre was invaded by Amarillans who wanted to see Oprah and hear her talk with her fake Texas accent. They loved the Texas that she had recreated for them—a Texas with a golden, nostalgic glow, a Texas where everyone was friendly and funny, larger than life, and able to ride a horse. The fact that her mythological Texas had little connection to reality didn’t seem to matter. Indeed, at the end of every one of her shows, Texans stood and roared their approval, prouder than ever of who they thought they were.