Sometimes it’s Wyatt or I who cracks first, but usually it’s Charles. An early riser, he leaves a rambling, semi-comprehensible five-in-the-morning phone message on Wyatt’s studio voice mail that concludes with the admission that he is in desperate need of a pork chop. This last part is what makes these calls at least semi-comprehensible; Wyatt and I may not understand much, but we understand pork chops. We quickly set a date for our next meating.

This is what happens at a meating. Wyatt McSpadden, Charles Lohrmann, and I gather at Wyatt’s East Austin studio at eleven in the morning and drive forty minutes to the venerable Kreuz Market in Lockhart for barbecue. This includes at least one pork chop each, along with some combination of brisket, prime rib, and sausage. Then we turn around and drive home. The whole meating, including drive time, takes about two hours. In the days before each meating, we are filled with anticipation, in the hours after, with satisfaction.

There is a downside to such unbridled consumption; my doctor, for example, who has been trying to teach me about blood pressure and cholesterol, will likely be somewhat disappointed in me should he read this article. But the benefits are immeasurable, and the pork chop is the catalyst; it’s also the reason I often refer to Kreuz as “the chop shop.” I don’t remember for sure who told me, when I first moved to Austin some fifteen years ago, that if I was going to eat at Kreuz, I had to have the pork chop. It may have been my writer friend Richard; I know it was Richard who warned me that if I wanted prime rib, I had to get there before noon, “when the lawyers come for lunch and buy it all out.” That’s why, ever since Wyatt and I began our meatings—about eight years ago, with Charles joining us a year or so later—we’ve always left at eleven.

We have often suggested to others that our meatings have spiritual overtones, though none of us can explain it, except to say that eating at Kreuz makes us feel very good deep in our souls. There are other, more concrete benefits. I had just met Wyatt, then new to Austin, when we made our first Kreuz run; we have since become best friends. But because we both travel frequently—I as a freelance writer, he as a freelance photographer—we sometimes have trouble hooking up. Likewise, I worked with Charles for a year in the mid-eighties but never got to see him as often as I would have liked after that. Pork chop grease has become the glue that binds us together. On the way to Lockhart, we have plenty of time to catch up with one another’s recent triumphs and tribulations. Once in line at Kreuz, we debate among ourselves what we’ll order on this fine day. The first one to get his meat and bread and/or saltines usually goes into the other room and buys drinks—always after asking what the others want, though the answers are always the same—and some jalapeños and wedges of onion. (Kreuz, which began life in 1900 as a market that sold smoked meat on the side, still includes a meat market and is famous for its no-sauce-no-sides policy.) Sometimes we eat in silence; sometimes we can’t stop talking about how good it is. On the way home, we discuss the nuances of our individual chops—tenderness, texture, aroma, fat-to-meat-to-bone ratio—or talk about jobs (Charles is a technology writer), recent travels, or somebody who isn’t in the car with us.

But there’s often somebody in the car with us, for we believe in sharing. In fact, we’ve been known to harangue and berate a newcomer who hasn’t ordered a chop until he joins us in having one. We want him to feel good. Among our occasionals are writer friends Jim and John; my L.A. friend Dick, who comes to Austin twice yearly for a record collectors’ convention; and various others connected to Wyatt through photography (including, at one time, Machine Gun Sam, who worked in a photo lab but spent weekends with his machine gun club reducing to dust old refrigerators, massive ice sculptures, and whatever else they could pony up money for). Once, the iconoclastic Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro joined us; upon his first bite, he began pounding the table and shouting in tongues, though we clearly heard him repeat the word “orgasm” over and over.

You can be sure that it was one of the great traumas of our lives when owner Rick Schmidt revealed last year that, after a dispute with his sister, Nina Sells (who owned the property where the market had stood since its beginning), he was moving Kreuz into huge, modern quarters about a mile north on U.S. 183. We held a teary-eyed meating as the original chop shop was being vacated and then crossed our fingers.

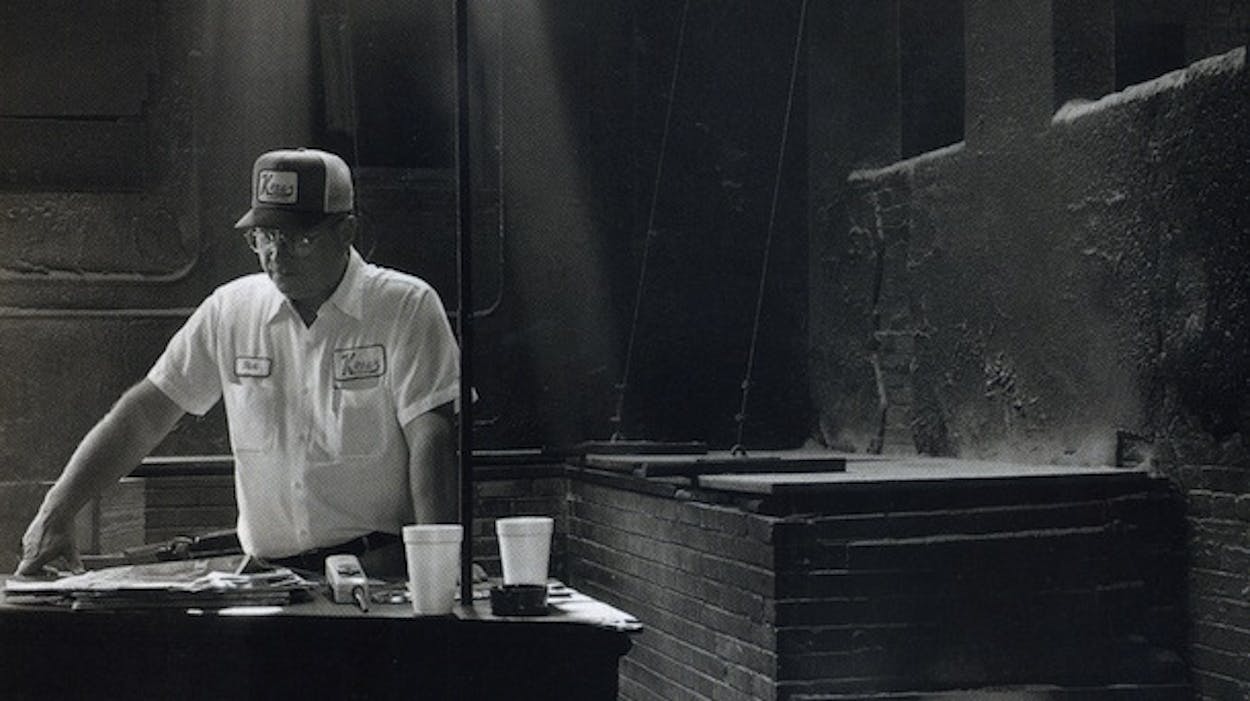

I was the only one able to go to the new location’s opening, on September 1. I contemplated my maiden chop for several minutes before taking a bite; after all, I’ve always argued that one shouldn’t eat at new barbecue joints until they’ve had about twenty years to break in the pit. But this chop was as good as ever—juicy, ambrosial, with an unbeatable sear. I hurried home and expressed great relief to my friends’ voice mails. The new place is a barnlike structure that holds six hundred, as opposed to the old location’s two hundred, but we figure that it’s pretty nice, as far as these things go. The walls aren’t covered with those reassuring splotches of grease and smoke, and flames from the open pit don’t lick at your legs anymore as you stand in line, but you can still feel, taste, and smell the smoke that the high-ceilinged pit room retains. You can sit either in the air conditioned main dining room or out on a cozy screen porch. There are still no side dishes, just the best barbecue in Texas—and therefore the world—and a few condiments. Most important, the old gang is still there. Rick stands somewhere around the pit, overseeing the whole operation, with his two sons, Leeman and Keith, who are the general managers, nearby. Pitmaster Roy Perez makes sure his charges do it right. And Ella Townes still takes your money at the pit room’s cash register.

We’ve heard from friends who have eaten at the cleaned-up old location—now called Smitty’s and run by Rick’s sister, Nina—that the food (which includes beans and potato salad) is good and the prices are considerably cheaper than Kreuz’s. But we’re unlikely to ever find out. Kreuz is a Texas tradition within a tradition—the vanishing one of independent, family-run, meat-market barbecue joints. The meating is our tradition, and since nothing is broke, we’re not about to fix it.