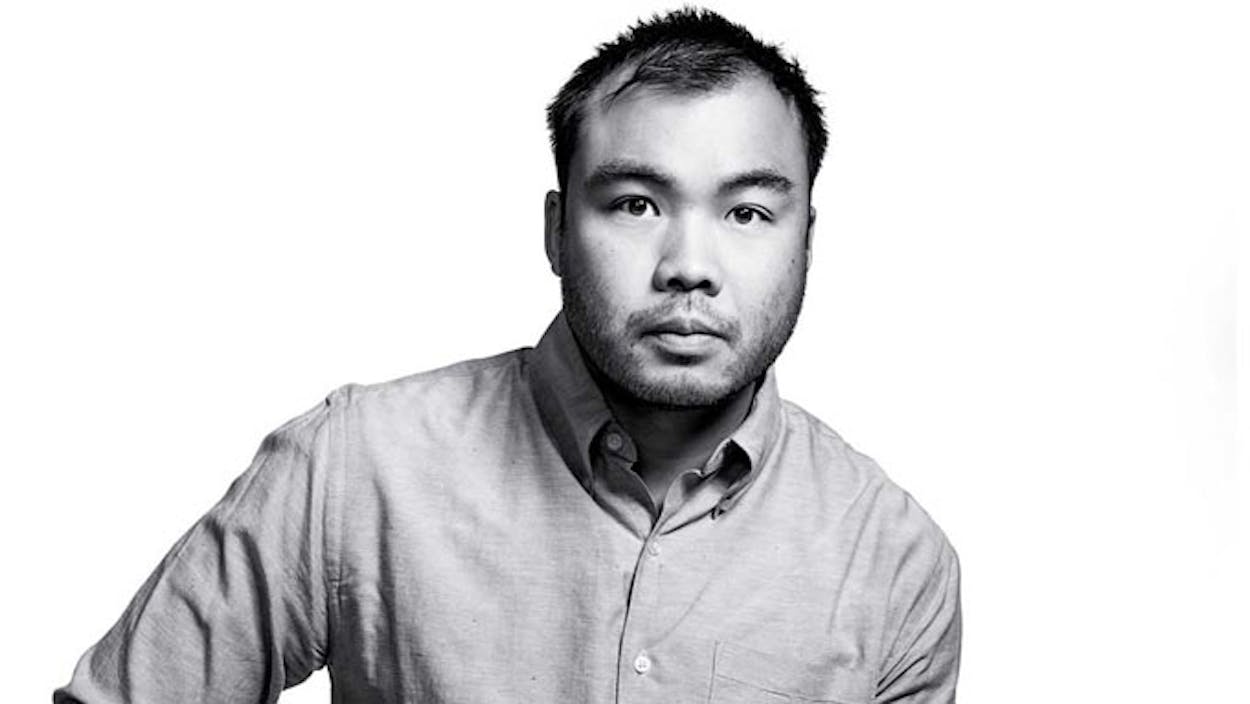

JAKE SILVERSTEIN: Some people know you and your food from watching Top Chef, some people from eating at Uchi or Uchiko. For people who don’t know you, how do you describe your food?

PAUL QUI: I’m still trying to define what my food is. There’s definitely some bold flavors. I use a lot of aromatic herbs from Southeast Asia. I like a little bit of heat. I like a lot of acid. One thing that I’ve definitely focused on is finding flavors that cross cultures. I worked at Uchi, and people are like, “Oh, that’s a Japanese fusion restaurant or whatever.” But I’m trying to push past fusion. I don’t want my food to be defined as a fusion of cuisines, because I mean, like, for example, if you were eating a taco in Japan, and they didn’t have a lemon or a lime they would probably use a yuzu or a sudachi, you know? Those relationships are what I try to explore.

JS: What are some examples of flavors that cross cultures?

PQ: There are certain building blocks, you know, salty or sweet or sour. I think the reason I like to explore food in this manner is that I’m from the Philippines.

JS: You lived there until you were ten, right?

PQ: Yeah. So in the Philippines, it’s basically three hundred years of Spanish rule plus you have the Chinese, the Americans, and now the Koreans. But the end result is it’s an interesting mixture. So Filipino food has a lot of Spanish dishes. We have paella, we have arroz con pollo, we have adobo. If I told you the ingredients in the adobo that my grandmother used to make, you’d say, that’s not an Asian dish. It has bay leaf, garlic, vinegar. That’s really interesting to me, how things can work in both cultures. We have a style of pico de gallo, but our pico will have shrimp paste and Sriracha.

JS: And now you’re in Texas, where Mexican flavors are so predominant.

PQ: Yeah, totally. And I didn’t really know anything about Mexican food for a big part of my life. My first Mexican experience was at a restaurant called Chi-Chi’s, which is a chain on the East Coast. You know, I got a cheese enchilada, and my mom had a margarita. I still don’t know that much about it, actually. But Southeast Asian food has the same line on the equator for the most part as the Latin or South American cuisine. And there’s the same notes, there’s the same hits of acid, the same hits of fresh flavors, like fresh herbs. The food is very bright.

JS: Let’s go back to Uchi, where you worked for eight years. We’ve been talking about a lot of different types of cuisine, but you came up in a sushi context. What’s the greatest lesson you took from the Japanese tradition?

PQ: To me it’s creating the perfect bite. I actually didn’t realize what that meant until last year when I went to Japan and ate at sushi bars where you don’t dip your sushi in soy sauce or wasabi because they give it to you and it’s already prepared. That’s what I had been trying to do at Uchiko, but I didn’t have a reference point. In Japan the sushi is already dressed for you. It has different sauces, different toppings, the right amount of wasabi. Most Japanese restaurants in America can’t ever hit that level of perfection, because they’re serving one hundred people, two hundred people. Jiro [Ono, proprietor of Sukiyabashi Jiro in Tokyo, and the subject of the film Jiro Dreams of Sushi] serves ten. So for me, that was the biggest lesson—mastering all the subtle details that make that bite special. The thing with sushi is you can’t hide anything. If your rice is bad, it’s going to suck. If your vinegar is bad, it’s going to suck. If your fish is bad, it’s going to suck. You can’t hide it with sauce.

JS: What about the intimate relationship between the chef and the diner?

PQ: I liked that interaction a lot. I had waited tables in Houston at a sushi restaurant, and I really dug what the sushi chefs were doing and that’s part of the reason I went into Japanese food. Another part of it was they had cool knives.

JS: I know Uchi isn’t a traditional place, but did you ever chafe against those limitations of preparing sushi? You seem like a guy who’s always got new ideas.

PQ: Well, yeah, but we always did new things at Uchi. Tyson was putting salt on fish, and they don’t do salt on fish in Japan. I can’t ever see myself adhering to certain rules, you know? I know there are certain scientific properties that you have to do with food that you probably can’t change, but as far as exploring flavors and combinations, I think it’s important to not limit yourself.

JS: After six years there you launched East Side King, which is now a collection of three food trailers and a brick-and-mortar location too. What drove you to leave the nice Uchi kitchen and start doing food trucks?

PQ: Um, I thought it was going to be a fun idea. I mean, we did it at a bar we were hanging out at. The owner had kicked out his old food truck and he knew that we were chefs so he asked if we wanted to do a food truck. A few weeks later, Moto [Utsunomiya, Qui’s partner in East Side King] calls me and tells me he has a food truck.

JS: The actual truck itself?

PQ: Yeah, and he found it on 11th and Comal, maybe, you know. So we were like, all right, let’s do it.

JS: And now you have the most well-known food trucks in the city that’s famous for food trucks. What’s the secret to success with food trucks?

PQ: You got to work a lot. I’ve been battling for the last three years just trying to keep my people inspired. That’s always a very big problem. The hours are late, you’re in a truck, the conditions aren’t ideal. But the important thing is to persevere and to work at it every day.

JS: You seem to really relish making this exceptionally fine cuisine that could be plated at a fancy restaurant and sold for twenty-five bucks, except you’re serving it on paper plates to drunk people. It almost seems like a conceptual art piece.

PQ: For me though it’s like, in Japan, street cuisine is amazing. You throw it in any of the restaurants in the city and it’ll be great. And it’s the same thing in Mexico City. The markets and the street food are amazing. For me the food truck thing was important because it’s like shaking the scene up a little. The running capital is really low on it, so you can spend the money on the food, you know, less on fancy plates or chandeliers and stuff like that.

JS: Some of the dishes at East Side King are just these big piles of deliciousness that seem like they’re going to fly out of control, but then you pull them off. It’s definitely wilder than the composed dishes at Uchi and Uchiko.

PQ: Well, if you’re going to spend more than five bucks at a food truck, the expectation is you’ve got to be full. And the other thing is like, there were a lot of dishes at Uchi where I would be like, “Oh, this would be great on a bowl of rice!” But we don’t do bowls of rice there.

JS: Austin’s culinary identity has changed dramatically in the past ten years. How important a role does the food truck scene play in the emerging culinary identity of this town?

PQ: I think it’s pretty big. A few years back when it started to get really, really popular, a lot of the old guard restaurants were complaining about how it’s not fair because the food trucks don’t have the same regulations. The way I was thinking about it, it’s like, man, they should have just made their food better. And so I think the food trucks have forced restaurants to be better.

JS: Let’s go back to Top Chef for a second. Last year you won the competition. And you also appeared to be the most uncrazy person in the cast. What’s the difference between watching the show and being on the show?

PQ: I have a hard time watching the show now because I get stressed out watching it. But actually I used to get stressed out watching it before too. It’s just not very relaxing after work when you just want to chill. If I caught it on TV, I’d watch it because it’s interesting, and then it would keep me up because I start thinking.

JS: Like about different decisions you would have made?

PQ: Yeah, or different things with food. After leaving a long, fourteen-hour day, you don’t want to think about anything that has to do with restaurants. That’s why most chefs eat badly. It’s like, you leave and you want to check out a little bit.

JS: Top Chef is a reality show but it’s obviously very crafted. Did you feel like you were getting up every morning to play Paul Qui?

PQ: They designed that show really well in terms of logistics, in terms of the way they create your experiences. They put you in really high stress situations, they don’t give you a lot of time, they don’t give you a lot of sleep, and you don’t even know really when you’re going to wake up.

JS: You mean they’ll just roust you up?

PQ: Yeah, I don’t know if I’m supposed to be saying any of that, but yeah. Let me put it this way: you’re not in control of when you get up every morning.

JS: So it’s like in an interrogation situation? Wow. Did you get water boarded by Padma [Lakshmi, the host of Top Chef]?

PQ: No, but they put you in a lot of positions where you have no control. But I just kept thinking that the one thing I know how to do is cook. Everyone else went crazy because they were trying to guess what was expect each day. I’m like, “Dude, I work in a restaurant. I have no expectations, and I never get surprised. Shit goes down every single day in a restaurant.” So in that situation, I know I’m going to cook. That’s the only thing that’s going to be one hundred percent today, you know, so that’s all I’m going to focus on.

JS: So after the show was over and you won, you then won the James Beard Award for Best Chef Southwest. What did that award mean to you?

PQ: It was big, man. Top Chef was cool and all, because it gave me more mainstream attention, and opened a lot of doors. But James Beard is a totally different story. I feel like maybe if I didn’t win both of them I wouldn’t have been able to collect the crew that I have here in Austin. A decent amount of my core staff here at the new restaurant is from out of town. These guys are leaving their positions at restaurants that are really amazing, some of them are the best restaurants in the country, restaurants I still want to eat at. And they decided, “Hey, we’ll move to Austin.”

JS: That must put a lot of pressure on you.

PQ: Oh yeah. I mean, in a good way. For me it’s like, if everybody is as talented or more talented than me, then it’s going to create some really cool food. People think, you know, this is the chef of the restaurant, this is the food he makes. But I’ve never met a chef that made the food, you know what I’m saying? There’s always a massive team behind him. So what I’ve been trying to focus on here is creating a team. It’s like creating a basketball team and having a good coach. It’s not just about that one person. So winning James Beard and Top Chef has been great as far as me bringing cooks to this city. Because I mean I went to culinary school here and a lot of kids I went to school with were like, “I’m going to move to New York so I can work at Daniel. I’m going to move to New York so I can Per Se or whatever. But now it’s like, now I feel good about my crew because they moved back here from New York, San Francisco, or Chicago.”

JS: So let’s talk about the new restaurant, Qui. This is your first place from the ground up. When you’re opening a restaurant from scratch like this, how do you develop the concept?

PQ: It starts with the people. So first we found the architects. We liked their design online, we contacted them, and they started giving us ideas. June [Rodil, the general manager and manager of wines] had contacted me initially, and I know she was passionate about wines, so boom, there’s another piece that fits. And then we started talking about how we wanted everything to be very well rounded, with the selection of beverages, plates, coffee everything. So we were like, “Oh Houndstooth [Coffee, a local Austin coffee purveyor]. Boom, let’s contact them.” And then for tea, the Steeping Room. They’re from Austin, let’s contact them. And even down to the plates, like, Griffin is this local artist I met on Twitter, and now she’s helping us find plates. I guess I’m rambling, but it’s all very organic.

JS: It sounds like the way an artist might record an album.

PQ: Yeah, totally man. And I think the creative process for me, where I can develop the best ideas, is where I have a bunch of ideas in front of me from a bunch of different people. I feel like perspective is a very big part of it. I think perspective is what holds a lot of chefs back.

JS: How so?

PQ: I know for a lot of the people who I went to culinary school with, the model of the chef was that the chef is always right. It’s the chef’s kitchen, the chef’s food, chef, chef, chef, chef, chef. You know? But in the end, the most successful plates I’ve tasted, there’s a group of people behind them. And that extends outside the kitchen, you know? It extends to the front of the house, it extends to the people that designed the restaurant. It extends to the community that basically helps a restaurant flourish, you know. Like, I ate at like Meadowood [in California’s Napa Valley] and there’s a local artist there that makes all his plates. I go to Saison [in San Francisco], and he has relationships with his farmers and fishermen. I love that place. That was probably one of my favorite meals ever. It’s amazing, man. At the end of the day, the restaurant is built on relationships.

JS: I know you went through a lot of different ideas for this place. What was the worst idea you had that you threw away?

PQ: When I first won Top Chef I was like, “Oh I’m going to open a ninety-seat restaurant because I know it’s going to make me the most money for my investors.” But then I traveled quite a bit and I looked at other people’s restaurants in different parts of the world, and I realized that there’s no reason not to try and come up with a better product. So I had to convince my investors to take out basically forty percent of the seats. What investor in their right mind would do that? But that was really important to me, because I feel like after a certain point, I don’t think my food tastes as good.

JS: So let’s talk about the food, what will the food be like here? What kind of stuff will be on the menu?

PQ: The idea is simple. We’ll try to get the best ingredients that we can, and just start from there.

JS: So how does that actually work? Let’s say it’s asparagus season, you’ve got great asparagus, so you just start walking around and thinking about asparagus dishes all day long?

PQ: Can I show you my board? [Walks over to his office, where a wall is covered with small tags representing different ingredients]. So we list out all our ingredients up here. I’m a visual guy so I need visual things to play with. There’s no organization to the whole thing, except that if they’re clustered together then it’s possibly a dish. So like rabbit, I want to do rabbit, we can do it seven ways. Then I have notes on how to prepare the rabbit seven ways. Or sweet potato leaves with catfish. So catfish, sweet potato leaves. If it’s a big tag then it might be a dish on its own. The smaller tags are preparations or ideas, the bigger things are possible dishes that we might work on.

The idea board at Qui. Sweet potato leaves and catfish are in the upper right hand corner. Rabbit Seven Ways is in the center.

The idea board at Qui. Sweet potato leaves and catfish are in the upper right hand corner. Rabbit Seven Ways is in the center.

[Walks back to table] With something like asparagus, it’s pretty easy, because you just take asparagus and then you list out every single way to cook it. So you boil it, you steam it, you fry it, you know, and then at that point, we decide which is the best application for what we want to do to it.

JS: Do you ever just Google “asparagus”?

PQ: Yeah, I mean, we could ferment the asparagus, like we pickle it, we see what other parts of the asparagus are edible. You know how asparagus has a bunch of little bumps on it before it reaches the top. There was a dish at Alinea [in Chicago] where they had somebody remove those. That’s why eating at Alinea is going to cost you $400. Because someone had to trim those asparagus sprouts. I mean that takes hours to do. If you’re going to serve asparagus sprouts you have to have a bowl of them. And that’s going to take you I don’t know how many cases of asparagus.

JS: So you’ve been doing a lot of preparation for the menu here. What’s one ingredient you’ve been really excited about lately?

PQ: The green garlic is really cool. The strawberries last month were really good. Honestly I don’t know. See this is a problem with developing a menu that’s seasonal. Our whole menu that we were going to do is almost all done. So the menu that we’re doing now is different. The rabbits are really good.

JS: So do you just carry around the idea of a rabbit in your head, thinking of different ways to prepare it?

PQ: I’ve served rabbit before at Uchi and Uchiko. My opening menu at Uchiko had a rabbit terrine. But I always wanted to serve the whole rabbit. Every time I’ve had the whole rabbit at different restaurants it’s always been like a braise where everything’s in the braise and it’s with pasta or something like that. And, since I like to eat a lot of good Vietnamese food, I’m like, “I’m going to do rabbit seven ways.” You know, like beef seven ways? So I’m basing it off the Vietnamese dish and I’m thinking all right, there’s also that thing where animals taste like what they eat. So like with rabbit, I’m like, “Why don’t I make it with carrot juice?” So our dipping sauce is made from carrots.

JS: How important is originality? Do you try to steer away from things other chefs have done?

PQ: Yes and no. I think there are certain things that are iconic to chefs. But you know I also have a dish on the menu that’s basically an ode to Michel Bras [the Michelin-ranked French chef]. His book [Essential Cuisine, published in 2002] inspired me a lot early on. I mean he’s the guy that started the whole garden plate thing. That’s probably the number one most copied plate of all time. So I have a dish on the menu named after him. But then also I’ll have preparations like Cote de Boeuf on the menu, it’s like an extra thick ribeye, very costly. And the reason we have that on the menu is that it’s just fun to cook. It’s fun to cook big pieces of meat. You have to baste, and cook, and take care of it, and it takes hours to cook. So what I’m looking for is the originality of the experience for the guest.

JS: You’re across town from Tyson Cole, who was your mentor for many years. Are you guys competitive with each other?

PQ: I don’t know. I mean Tyson’s not a competitive guy. They just do what they do. I’m kind of the same way.

JS: Is this going to be, is this restaurant, do you see it as a place that people come here two or three times a month? Is it going to be a special occasion kind of a place?

PQ: That’s the whole reason why I wanted a ten-seat section and a fifty-seat section. In the fifty-seater, the plates are more large format. You can order one or two things and you’re done. I see it as a neighborhood spot where you can come in and eat multiple times in a week. The ten seater’s going to be more of a special occasion thing. At first, I’m only going to do ten seats a day.

JS: You seem like a pretty humble guy, but you’ve got a lot of accolades in the last year, and the restaurant is named after you. It seems like you’ve embraced the celebrity chef thing. Is it something you enjoy? Or does it seem like this necessary evil

PQ: I don’t know, man. I don’t think I’m the best at it, but I know that it’s important. The more that I can push that, the more I can do my restaurant. The more attention I can bring to Austin and our restaurants, the better the scene’s gonna be. Ten years ago, if you were a cook from Austin, and you went to any city, they would be like, “Eh, a cook from Austin, whatever.” But having that celebrity, having that attention here in Austin, helps drive chefs from out-of-town to Austin. But I’m cautious about using the term celebrity chef, because there are celebrity chefs that are just a face, and I actually cook in my kitchen. I embrace the celebrity because it can get more attention for Austin. I think once you hit celebrity status, it’s your responsibility to promote your city, to promote your region. So yeah, it’s important.

JS: Do you also feel like it’s your responsibility to try and kind of push the public’s palate?

PQ: Yeah, I think so. But there’s a balance to that because we’re in the hospitality industry. So it’s not like, “I’m the chef. Here’s the food. If you don’t get it, you’re wrong.” You know? It’s like being in a relationship, you know? You slowly cultivate that.

JS: I wanted to just ask you a little bit about your history. You were born and raised in Manila, and you came to Virginia when you were ten.

PQ: Yeah. Springfield, Virginia.

JS: Then you moved to Houston to go to University of Houston. How much of your approach to food think comes from having spent your life moving between different cultures?

PQ: In the Philippines, I ate a lot of home-cooked meals. But when I moved to Virginia, I ate a lot of frozen food, and microwave bacon, and canned cheese. My mom worked a lot, and we used to go to Costco, like, once every two weeks. And then, like, that would be kinda like my food throughout the week.

JS: You weren’t into cooking at that point?

PQ: No.

JS: What were you like in high school?

PQ: I was kinda just there, you know?

JS: On Top Chef, you talked about how you sold weed in those days.

PQ: Well, no, it was high school and college. Yeah, I sold drugs.

JS: Were you a good drug dealer?

PQ: No, I was like a horrible drug dealer. I was the worst drug dealer. Like, if I had acid, or ecstasy, or whatever, I’d just give it away. Or I’d take it with my friends. I was the worst type of drug dealer. The problem was that for me, it was more about hospitality, I guess. It was more about having fun than it making money.

JS: Which is kind of the same thing as cutting forty seats out of your new restaurant.

PQ: [laughs] Yeah, I guess that’s true isn’t it? But then I just woke up one morning and like, my apartment was a dump, and I thought, “I don’t know what I’m doing. I gotta figure it out.” Up to that point, everything in my life was like a mess. I don’t think I had any money at that point.

JS: What was down that other path that you didn’t go down?

PQ: I don’t know, man. It probably would have been bad. But at that point, I’d already been waiting tables in restaurants for like five years, at least. And I was like, “I really like making food. I really like the environment of a restaurant.” And I knew I needed a change in my life.

JS: You went to culinary school in Austin. But on Top Chef, it was the first time you cooked a certain classic Texas dishes, like barbecue, chili, Tex-Mex, or anything like that. What’s the traditional Texas food that’s closest to what you do?

PQ: Oh, I don’t know. What’s traditional Texas food?

JS: Well, any of the ones I mentioned—like barbecue or Mexican food. That sort of thing.

PQ: It’s funny, because when I think about Texas food, there’s definitely a big Asian influence to it. Moving from Virginia to Houston, where there were a lot of Vietnamese and a lot of Chinese, I had a huge exposure to that kind of food. So for example, I like to eat crawfish, which is Cajun, but it was from Vietnamese fisherman, so you get lime or different spices in it. So for me, when I think about Texas food, it’s more those kinds of tastes. Now that I’ve moved to Austin, I’m exploring the Mexican side of it a bit more. But for me, barbecue is pretty Asian, too.

JS: How so?

PQ: It’s just the— I mean, I think it’s very primal. You know? Like the grilling of meats in coal, cooking animals whole. It’s the slow cooking of tougher cuts. A lot of Filipino food is based off of tougher meats that you have to slow cook.

JS: So what would a Paul Qui barbecue joint look like?

PQ: A Paul Qui barbecue joint. Actually I’ve thought about that. I’ve thought about doing a barbecue joint. I had this idea of making a new Texas barbecue. I’d probably brine all my meats in fish sauce. I would do all the same cuts, but I would do different marinades and sauces. And different pickles. And I mean, if you look at, like, Korean food, basically it’s all about pickles, sides, and grilled meat.

JS: Something you said earlier reminds me of barbecue, too. You said, “In sushi, there’s nowhere to hide.”

PQ: Yeah, barbecue’s the same way.

JS: Let’s look ahead. What would you rather be known for, at the end of your career, a commitment to great ingredients or an incredible technique?

PQ: Technique. If you have excellent technique, you can work with less desirable ingredients.

JS: Where do you feel like your technique is today versus where you want it to be?

PQ: Far. I feel like I’m still in the infancy stages of developing my food and refining it. Uchi was a great learning ground for me, because the specials menu changes every two weeks. But in a lot of ways, there are a lot of ideas that I didn’t get a chance to explore fully. Like let’s say you’re making chicken soup, right? All right, we make chicken soup. It’s delicious. All right, how can we make it more delicious? So, where are these chickens coming from? You break it down. Who’s getting what chicken from where? Then you break down all the vegetables, and we’re like, “Who has the best carrot? Does Animal Farm have a better carrot this week than JBG [Johnson’s Backyard Garden, an Austin farm]?” I’m pretty sure most people don’t think about it that way. A carrot’s a carrot. You know? An onion’s an onion. But here at the new restaurant, the way we’re testing it right now, and the way we’re labeling our walk-in, it’s like, who has the better carrot this week? Who has a better onion this week?

JS: It might be different next week.

PQ: Yeah, totally. So at the end of the day, it’s same ingredients, same recipe. But they’re from different farms. And when we put it together, it tastes totally different.

JS: It’s all about timing, right?

PQ: Yeah. And it’s playing with these factors, I think, that’s really cool. I was telling my cooks the other day, I’m like, “I want you guys to taste every single tomato that comes in here.” They shouldn’t be saying, “Hey, chef, I followed the recipe. Why is it different?” You should know why it tastes different. You should be like, “Hey, chef, I think it tastes different because today’s tomatoes came from this farm instead of this farm. These were a little bit greener.” It’s working on these little details, I think, that will make this place a really special restaurant.

JS: So obviously the supply chain’s really important. But Austin’s food scene’s still developing, so that supply chain is also still developing. Do you ever feel like you’re limited by the supply chain here?

PQ: It’s very limited. But at the same time, there’s an opportunity for it not to be. I’m constantly talking to the purveyors, pressing John Lash from Farm to Table, or talking to the farmers from Animal Farm. These guys want to make better product, they just need pointers here and there. I don’t know how to grow, but I can tell them that last week was better than this week, and then maybe they can figure it out.

JS: So it’s a collaboration with the producers?

PQ: It has to be a collaboration. Like I was telling John, “Dude, if you guys don’t give me any food, I don’t have any food.” I’m not going to order food from so-and-so company. I’m trying to say without naming companies.

JS: You don’t want to order from the big giant food service companies?

PQ: Yes.

JS: I’m not surprised to hear you say that.

PQ: Yeah, but like I’m really good friends with Matt Doll. He’s my US Foods rep and he was my US Foods rep at Uchi, but I’m like, “Hey I’m opening Qui but I’m not buying any food from you. I’ll buy scrubbies, paper towels, soap, but we can’t buy any food.” For me it’s more like focusing. If our guys can’t get us an ingredient for a dish then we’re changing the dish. Part of the reason to have a small menu is that I can change it. I don’t have to have the sunchokes in August or the tomatoes in December.

JS: What you have, you’ll work with.

PQ: Exactly. And part of that is training my guys, and part of that is training the purveyors. And if you look at some of the greatest restaurants, they’re in the middle of nowhere. Like El Bulli, which is in Roses, Spain, Granted they have the ocean, which is huge. But there was nothing else around. Barcelona was a few hours away. I couldn’t imagine how they got some of their specialty items. It would have to be a huge planning process. Or Noma. I mean, when was Copenhagen known for food? [Chef René Redzepi] has barely anything there and he had to go look for it, forage things you know to put pretty things on his plate. A lot of great restaurants in Europe are not in the major cities. They’re in smaller towns, you know, and places that are not so easy to get to. That’s the whole reason for the Michelin guide, to not be centralized in the big city but to make sure people would drive around the countryside to these great places. And they all had to start from somewhere, they all had to start from nothing. I still have chef friends who are like, “Ah, we get such shitty product here in Austin.” And I’m like, “Yeah, we do, but it’s our job to change that.” It’s just a matter of cultivating those relationships. The opportunity is here we just need to be able to guide it correctly.

JS: You’ve lived in both Houston and Austin. What’s the best food city in Texas?

PQ: Best food city in Texas. That’s a tough one man. But just because of the diversity, Houston. A couple of the most forward restaurants in Texas right now are in Houston. The Pass & Provisions, Oxheart, and Underbelly. It’s great what they’re doing with the food scene. And Houston has the best ethnic food. Indian, Middle Eastern, Korean, Vietnamese, Chinese, you name it. There are some okay Chinese restaurants in Austin, but there’s nothing great. When it comes down to it, Austin’s still a growing city and we don’t have that kind of food here yet. But as far as the restaurant scene goes, I like the vibe in Austin better.

A condensed version of this interview ran in the July 2013 print issue.

- More About:

- Tyson Cole

- Paul Qui