“There are no words in any language to express truly our grief and the sympathy we wish to extend to you and your family on the death of your husband, the President—our President,” wrote sixteen-year-old Marcy Wentworth on the cold, rainy afternoon of November 25, 1963, as she bent over an ivory sheet of Crane’s stationery. Her bedroom, in her family’s northeast Austin home, was her sanctuary from her four younger siblings, and it was there—after three wrenching days of watching TV news reports about the assassination—that she tried to articulate her sense of loss. A red Royal typewriter sat on her desk, but she had decided to write the letter by hand, so that Jackie Kennedy would see her sincerity. “We Texans pride ourselves in our state,” she continued. “That such a perverted act would happen here doubles the weight of grief in our hearts.”

Wentworth had woken up three days earlier—when John F. Kennedy was in the midst of a five-city swing through Texas as he campaigned for reelection—expecting that she would see him in person. He had been scheduled to speak at a fund-raising dinner that evening in Austin, after his visit to Dallas. Wentworth and several other Austin High School students, who had organized a committee they called Youth for Kennedy-Johnson, had been invited to the dinner, and Wentworth had purchased a pale-gold ball gown for the occasion. But when she was in PE early that afternoon, a teacher ran onto the field with the news that the president had been shot; not long afterward, sitting in geometry class, she heard the principal’s announcement over the public address system that he was dead. Wentworth started shaking so violently that her geometry teacher sent her to the nurse, fearing she might suffer a seizure. After school let out, she and several members of Youth for Kennedy-Johnson walked to a nearby church and prayed. Later that afternoon, when she returned home, she found her taciturn father—a retired Air Force colonel and former prisoner of war—silently weeping in the kitchen.

Wentworth made no mention of any of this in her letter. She was writing in her official capacity as the “Deputy Corresponding Secy,” she noted, for the Youth for Kennedy-Johnson committee. Instead, she drew on the grandest language she could think of to impart the enormity of her grief. “Here in Texas—here in our city the sunsets are blood red and the streets flow with tears,” she wrote. “The only sound heard is that of crystal silence, rippled occasionally by a single bell that tolls a solemn requiem.” She was careful not to smudge any ink as she moved her mother’s fountain pen across the page, filling it with her left-handed script. “Our prayers are with you, your small children, and the other members of your family,” she wrote in closing, expressing her “deepest hope that somewhere in your private heart you can find [the strength] to forgive the twisted mind, to forgive Texas, and to forgive us, the nation.”

Wentworth was hardly the only Texan who wrote to Jackie in the wake of JFK’s death. Of the more than 1.5 million condolence letters that the first lady received, a surprisingly large number of them came from Texas. As residents of the state recoiled at what had happened in Dallas, they expressed not only the disbelief and horror felt around the country but their own particular anguish that the president had been murdered in Texas. “I know the grief you bear,” wrote fourteen-year-old Tommy Smith. “I bear that same grief. I am a Dallasite.”

Half a century later, our collective memory of the assassination is fading. Many of us are too young to remember it; just over a quarter of Texans living today were alive in 1963. The stain on our reputation is no longer too painful to discuss. Pop culture has long since appropriated the assassination, obscuring its solemn importance with conspiracy theories and enshrouding it with Camelot mythology. Even its awful novelty is gone; with each subsequent national tragedy, its power to shock has receded. But the horror of November 22, 1963, and the raw emotions that gripped Texans in the weeks and months that followed are still on display in the letters they sent to the first lady. Here, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Kennedy assassination, we present thirteen of these artifacts, all of which make the past come startlingly alive again.

Written by a remarkable cross section of people from around the state, they capture a moment in history when Dallas—and by extension, all of Texas—shouldered the blame for one man’s crime. “I feel I must tell you how VERY ASHAMED I am to be living in this city,” a Dallas resident named Robert Wood confided in his letter to Jackie. “Dallas—a city of cultural background—a city of colleges, schools and supposedly intelligent people. God would that I could move from this place this hour.” Henry Gonzales, an El Paso postman, sought to reassure her that Texas was a welcoming place. “[W]e Texans of Mexican descent had a great love for all of you,” he told her. “We do hope that you will not think all of us Texans were bad, there is bad in every sort of people as you well know.” A seven-year-old boy from Dallas named Monroe Young wrote simply, “Some mean man killed my dad[d]y too.”

Several Texans whose letters are pictured here had personally seen the Kennedys in the days, and even hours, leading up to the assassination. “I must pour out my heart to you if my feeble hands will hold out to scribble a few lines,” wrote 76-year-old J. E. Y. Russell. “I was at Love Field, when you and John step[p]ed from the plane. I was the first man to shake his hand, (from behind the fence barricade). That was my life’s fullest moment.” Ten-year-old David McClain—who had glimpsed the Kennedys at Carswell Air Force Base, in Fort Worth—informed Jackie that he “cried for two or three minut[e]s” when he learned that the president was dead. “He was my friend even though he didn[’]t know me,” McClain added. Claudine Skeats, a secretary at Brooks Air Force Base, where the president had delivered a speech, told of meeting the Kennedys in her office. “I will forever be haunted by how handsome and healthy and happy you two looked—and how gracious you were to me. We loved you here at Brooks and feel your loss especially deeply.”

Skeats cautioned Jackie not to be “consumed with bitterness,” even though she acknowledged that the first lady had every right to be. “I have learned through the years that you can live with sadness but you cannot live with bitterness,” Skeats wrote. “It destroys you and those dear to you. My husband, a B-29 pilot, was killed during World War II when I was three months pregnant with our first baby.”

These letters, and thousands more from around the country, might have been lost to history if not for Ellen Fitzpatrick, a professor of American history at the University of New Hampshire. Four years ago, while conducting research at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, in Boston, she came across the little-known Condolence Mail Collection. She was astonished by the diversity of voices—the first letter she read had been written by an Inuit—as well as the immediacy that the letters lent to a tragedy that had occurred so long ago. “One woman wrote that she was crying as she was writing, and I could actually see where her tears had fallen onto the page and smeared the ink,” Fitzpatrick said. Curious about what else she might find, she began making daily pilgrimages to the library’s sun-filled research room. Many letters had been written by hand, and Fitzgerald had to study them closely to decipher the words. A few were embellished with notes in the margins, jotted down by the White House staffers and volunteers who had originally sifted through the mail. They had made their appraisals in red pencil, deeming certain letters “special” or “touching.”

When Jackie bequeathed the letters to the library in 1965, the cardboard boxes that held them would have measured more than a quarter-mile long had they been laid end to end. But over the years, the collection shrank substantially. Some letters were discarded after they sustained water damage at an off-site storage facility; others were culled during the pre-digital age because the collection simply took up too much room. By the time Fitzpatrick began her research, the number of letters from Americans had dwindled to 15,000. Yet what remained was revelatory, and she spent six months combing through the collection. In 2010 she published Letters to Jackie: Condolences From a Grieving Nation, in which she reproduced the text of 250 memorable letters. They ranged from a one-sentence missive written by a junior at the University of Massachusetts (“I have never seen our football players cry . . . but today, they did”) to a telegram sent by the widow of recently slain Mississippi civil rights activist Medgar Evers. Letters to Jackie, a documentary directed by Academy Award winner Bill Couturié that draws on Fitzpatrick’s book, opened earlier this year in limited release around the country.

“At the outset of this project, one of my closest friends, who grew up in Dallas, told me, ‘I bet you’re not going to find many letters from Dallas,’ ” Fitzpatrick said. “He remembered the anti-Kennedy mood and the politics of the period, when Dallas was not a terribly hospitable place for President Kennedy. A few weeks into my research, I called my friend and said, ‘You’re not going to believe this, but there are tons of letters from Dallas and from all over Texas, actually.’ ” Those letters were filled with a tremendous sense of both guilt and responsibility.

The stigma that Texas carried after the assassination is still vividly remembered by many of the Texans who wrote to Jackie. Marcy Wentworth—the Austin High student who found her father weeping in the kitchen—remembers feeling the judgment of the outside world. “There was this sort of morbid curiosity, particularly after the Johnsons moved into the White House, about what weird people we must all be,” said Wentworth, now a retired first-grade teacher and reading specialist who goes by her married name, Marcy Leonard, and lives in Austin. Tom Smith—the Dallas teenager who told Jackie that he understood her grief—will never forget the chilling reception he received the following summer, when his family drove to the West Coast to see relatives. “We stopped in Riverside, California, and I went into a dime store there and bought myself a little toy dinosaur,” said Smith, now a consultant in San Antonio with the U.S. Army Reserves. “The clerk heard me and my brother talking, and he said, ‘Where are you from?’ And I said, ‘Dallas.’ He made a pistol out of his hand, with his thumb sticking up and his index finger aiming at me. Then he lowered his thumb like he was pulling the trigger and said, ‘Dallas.’ ”

Smith, who was fifteen at the time, was shaken, though he chalked up the encounter to what he saw as the clerk’s ignorance. “I still bragged on Dallas, and on being a Texan, whenever I could,” he said. But for others, the assassination shifted the way they looked at the place where they had grown up. Jane Dryden Louis—who, at the age of eleven, faithfully wrote to Jackie once a week for six months after President Kennedy was killed—found herself ashamed of her home state. “That’s when Texas began to look narrow and rigid to me, and when I started to develop this longing to go far, far away,” recalled Louis, now a pastoral counselor who practices in Austin. Still, she remembers being relieved that she lived in Austin, not Dallas. “When we went out to eat one day, I struck up a conversation with some people who were visiting from out of town,” she said. “And when I discovered they were from Dallas, I blurted out, ‘Oh, how awful.’ ”

The daughter of a white physician who cared for poor black and Latino patients in East Austin, Louis had seen more than most kids her age. Her father often took her with him on house calls or to the emergency room—“I knew about people getting shot,” she said—and once, he’d stopped at the scene of a car accident to load injured passengers into the family’s Cadillac. Yet the brutality of the assassination left an indelible mark on her. She constructed a makeshift altar in her bedroom, adorned with a piece of lace, a candle, and a photo of the late president. She and two friends in the sixth grade would somberly pace down the halls of their school, mimicking the way Jackie, Bobby, and Ted Kennedy had walked together in the funeral procession. She also wrote letter after letter. “Dear Mrs. Kennedy,” she began on January 18, 1964. “I know that you hate the whole state of Texas. I do to[o]. I wish I lived in Washington, D.C. where maybe I could . . . see you standing on your porch. I am determined to move there as soon as I can. I would feel safer there.”

The sort of grief counseling that Louis now provides was not offered then. Like Tom Smith and Marcy Wentworth, Louis cannot recall an adult ever taking her aside to discuss what she might be feeling. “Nobody sat down and said, ‘What do you think about this, Jane?’ ” she said. And so it was by writing to Jackie that she grieved. “There was so much hope invested in Kennedy and his presidency,” Louis said. “He was young and cultured, and he ushered in a new way of thinking. He was the ambassador of peace and camaraderie to the rest of the world. Even if you didn’t vote for him—or even if you were like my dad and distrusted him to some extent because he was Catholic—he still offered a sense of hope about the future. And when that was taken away, there was just this profound, earth-shattering heartbreak.”

Louis, like so many of the correspondents, hoped that Jackie might write back. “I checked the mail every single day,” she said. One afternoon the following spring, she received not one but four small cards in the mail. In place of a stamp, each envelope carried an imprint of the former first lady’s signature. Printed on ivory card stock with a black border and a coat of arms, each card bore a single, heartfelt sentence: “Mrs. Kennedy is deeply appreciative of your sympathy and grateful for your thoughtfulness.”

Read all thirteen letters to the first lady:

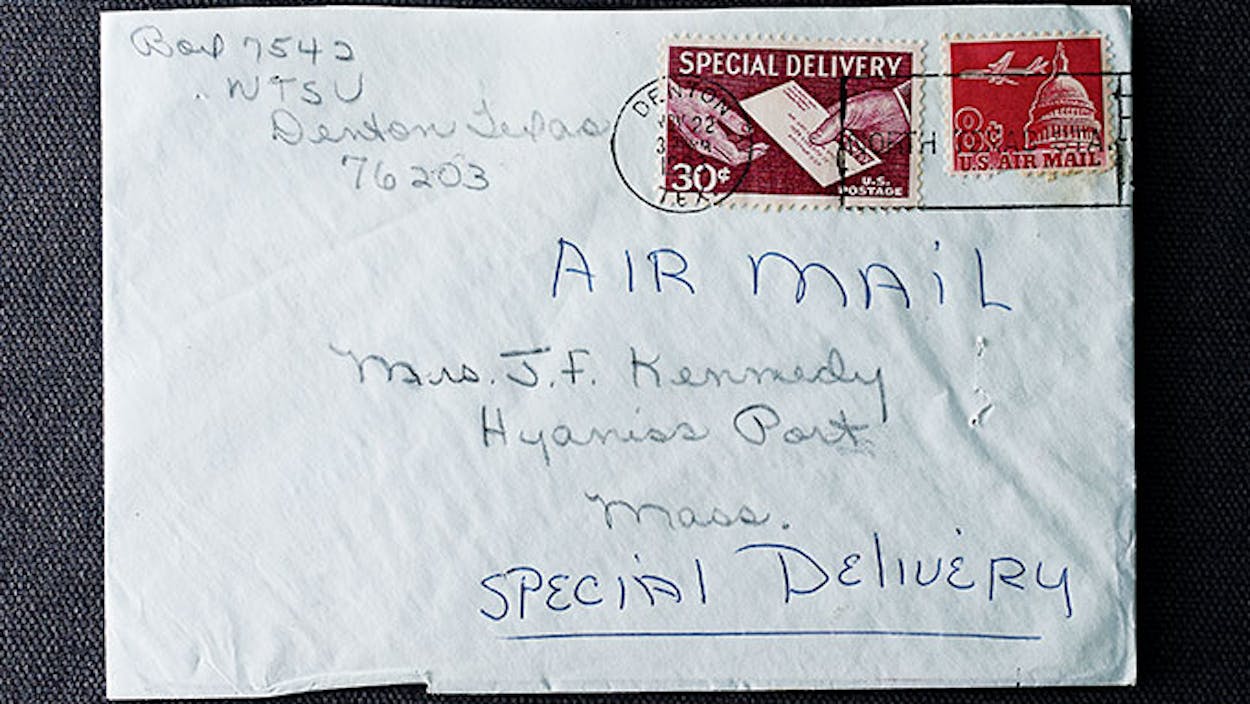

Marcy Wentworth’s letter

Suzan Lane’s letter

Tommy Smith’s letter

Claudine Skeat’s letter

Marie Tippit’s letter

Henry Gonzales’s letter

J. E. Y. Russell’s letter

Eileen Mitchell’s letter

David Blair McClain’s letter

Monroe Young’s letter

Jane Dryden’s letter

Mary McMillen’s letter

Robert L. Wood’s letter