Texans are no strangers to the universal human impulse to locate a golden age in the past: There was the Austin of yore, before the tech zillionaires arrived. Marfa, before the hipsters took over. The Cowboys, when Tom Landry was in his prime.

This truism applies to our literary legacy as well. It’s difficult for us to imagine that any contemporary Texas writer will be immortalized in statuary or have a middle school named after him à la J. Frank Dobie, Walter Prescott Webb, and Roy Bedichek. Or that anyone will describe the arc of our history as commandingly as Larry McMurtry did during the peak of his great, decades-long run.

But anyone who’s paying attention to the fiction being produced in Texas today can’t help but notice that we’re in the midst of a literary boom. Barely a week goes by without the arrival in Texas Monthly’s mailbox of a novel or story collection worthy of our attention. And an impressive—and, by unscientific guesstimate, growing—number of these books are very much about Texas. Ben Fountain, Elizabeth Crook, Oscar Cásares, Philipp Meyer, Sandra Cisneros, Attica Locke, and Dagoberto Gilb are just a few of the Texans who have already made names for themselves writing about their home state. Coming up right behind them is a new crew of writers who have likewise bucked the old publishing industry belief that Texas isn’t a serious subject. They are a notably diverse lot in terms of gender, ethnicity, age, and regional identity, hailing from and writing about nearly every corner of the state. In fact, the hardest part of creating the list of ten writers on the pages that follow was deciding whom to exclude; the bench is deep.

Undoubtedly, we will soon be able to assemble a list made up of entirely different, and equally impressive, writers based on the letters of protest that we’ll get in response to this story. How could you leave out Scott Blackwood? And Keija Parssinen? And Bill Cotter? And Bret Anthony Johnston? And Jacqueline Kelly? Because if there’s anything Texans like to do even more than look back with longing, it’s brag about how great we are right now.

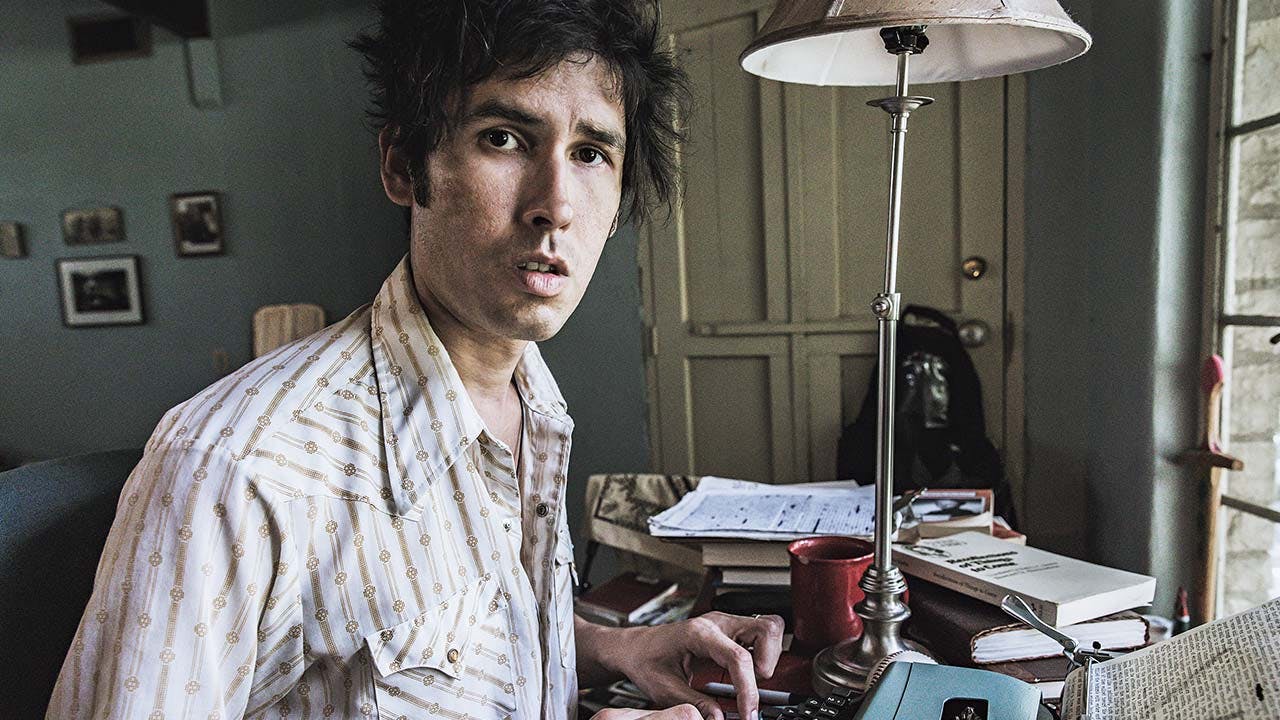

Fernando A. Flores

test abc

For a genial guy, Fernando A. Flores has a lot of enemies. Before his first collection of short stories, Death to the Bullshit Artists of South Texas, Vol. 1, was published last year, members of the Rio Grande Valley punk/emo/indie rock scene waited in hopeful anticipation of finally seeing their world faithfully depicted by someone who knew it well. But Flores, who grew up in Alton, just outside McAllen, wasn’t interested in that kind of documentation; he was inspired by that scene, but he didn’t feel compelled to stay true to it. Death was full of characters built around details—a stutter, for instance—that their real-life counterparts didn’t possess. Though the book was billed as fiction, many members of the Valley’s largely ignored music community felt that Flores had portrayed them in an unflattering light. The members of the Valley punk band Inkbag were particularly affronted. They saw something very familiar—and deeply insulting—when they read the story of “Pinbag,” an unflinching depiction of a trio of punk-rock losers. A few weeks after the book’s publication, Flores got word that if the members of the band ran into him, he might wind up with a few missing teeth.

Still, it wasn’t all bad news. The book’s run was small—only two hundred copies were printed—but those copies landed in the right hands, earning Flores an honorable mention award from San Antonio’s Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Foundation. That reception gave him a shot of confidence, leading him to complete a border-region novel about mythical beasts, exploited laborers, and foodie culture, which he is currently shopping around. Meanwhile, the 33-year-old writer spends most of his days sitting in the Austin house he shares with his wife, the poet Taisia Kitaiskaia, pecking away at an Olivetti Underwood Lettera 32 manual typewriter, next to a boom box and unruly piles of CDs and cassette tapes. On a recent afternoon, he took time away from his writing to submit himself to a blindfold test featuring songs from the Valley punk scene’s late-nineties/early-aughts heyday. Unsurprisingly, he recognized each one immediately.

We Suck, “Too Hardcore”

“I remember going to see We Suck at Room 710, in Austin. They played there on my twenty-first birthday. I was visiting from the Valley, and the bartender was giving me free shots. So by the time they got onstage, I was all sauced up. I was the only one there from the Valley, and [lead singer] Marc [Villarreal] liked to go up to people and get them to sing the chorus, so he came right up to me, because he knew that I knew all the words.”

Yoink!, “Stay Away From My Girlfriend”

“This song is great. I saw [drummer] Lindsay [Kinsolving] in Austin a few months after the book came out, when everybody started hating me, and she said something like, ‘Thank you for doing that.’ She didn’t mean ‘Thank you for writing the book,’ she meant ‘Thank you for pissing everybody off.’ I remember feeling really apologetic, and she was just smiling about it the whole time.”

Inkbag, “Ten Minute Love”

“I had no idea what I was doing when I wrote that story [“Pinbag”]. I love Inkbag. And it just got out of hand. I never thought that anybody would read it—that story was sitting in my drawer for three or four years. I didn’t mean any harm to them on a social level. But at the same time, they weren’t the best people in the world either. They wrote a song called “Danny’s Drunk Again,” about what a screwup their friend Danny was. And Danny was a real guy. They didn’t even change his name. When you’re twenty, twenty-one years old, that might seem cool. But what happens twenty years later, when you’re no longer that Danny?”

Charlie Daniels Death Wish, “Knife Handles (Mercenary Song #1)”

“ These guys were amazing. There’s a video on YouTube of them playing at Trenton Point [a former event hall in Edinburg], and Eric Fly’s guitar strap keeps coming undone, and he keeps struggling with it, but he’s also going insane, and at some point maybe he decides that it just doesn’t matter. Everybody in the Valley loved these guys. All of those bands wanted to be Death Wish. I saw that recent cover piece in Texas Monthly [“The Secret History of Texas Music,” July 2015] on the stories behind all these Texas songs, and I feel like there needs to be an alternative list. I was happy to see the Butthole Surfers there, but I’d love to see one about the great underground Texas bands that nobody knows about.”

Cynthia Bond

Cynthia Bond’s debut novel, Ruby, had the sort of reception every first-time author dreams of. There were rave reviews in Kirkus and People, and sales leaped when it was named an Oprah’s Book Club 2.0 selection. The story of Ruby Bell, a black woman from rural East Texas who descends into madness after a life of unspeakable violence and tragedy, has even been optioned by Hollywood, with Bond writing the screenplay.

But a small subset of readers hated the book’s explicit portrayal of various forms of abuse. One Amazon reviewer wrote, “It was so vile, there were many pages I couldn’t read.”

“People ask, ‘How can you write about things that are this difficult?’ ” Bond says, sitting in the dining room of her Los Angeles home. “I just say, ‘The stories that I’ve heard are far more difficult than the ones that I put in there.’ ”

Many of those stories are ones that Bond grew up hearing. The 54-year-old writer was born in Hempstead, an hour northwest of Houston, and lived there until the age of 6, when her parents relocated to Kansas. She remembers making the drive back for every wedding and funeral and spending summers at her grandmother’s home in Beaumont. “We always felt like we were Texans,” she says.

The book draws on a great deal of family lore, most hauntingly the handed-down tales of the unsolved crimes committed against two of her aunts. According to Bond’s family, nearly a century ago a white sheriff and his deputies targeted eighteen-year-old Carrie Marshall because she was involved in a relationship with her married white employer, whose well-connected wife, it is said, sought revenge. She was detained along with her sister Iantha, who was raped by officers. Carrie was killed.

Vintage photos of the two women hang on one wall of Bond’s dining room. Teenage Carrie is dressed modestly, sitting primly on a porch. In another frame, a grown-up Iantha strikes a glamorous pose, flaunting the stylish finger waves of the thirties. “Her whole life, my mother has wanted somebody to tell their story,” Bond says. “There’s been no justice.”

This fall, Bond plans to return to Southeast Texas with her mother to uncover more family truths, tall tales, and traditions for the sequel to Ruby, which is the first installment of a trilogy. They’ll spend time interviewing elderly family members who’ve never left the area. “Everyone has their own version of the things that happened,” she says. “Some of them are in their eighties and nineties; I want to talk to them before they die.”

But even while she’s delving deep into the past, it will be tough for Bond to ignore the present. Sandra Bland, whose recent death in a Waller County jail cell sparked a nationwide outcry, died in Bond’s hometown. And Bland was arrested while en route to a new job at Prairie View A&M University, where Bond’s father once taught English. Bond doesn’t yet have a concrete plan, but she can imagine the shape of the trilogy shifting to make way for today’s headlines. “The injustice,” she says. “It echoes.”

How Bond Kept Her Sanity While Writing About the Darkest Sides of Humanity: “I wrote one section of Ruby in a church. And I’m really glad I did! I know this sounds a bit odd, but I would say to the characters, ‘You are not coming home with me. If you want your story told, you have to stay here.’ I was going home with just me.”

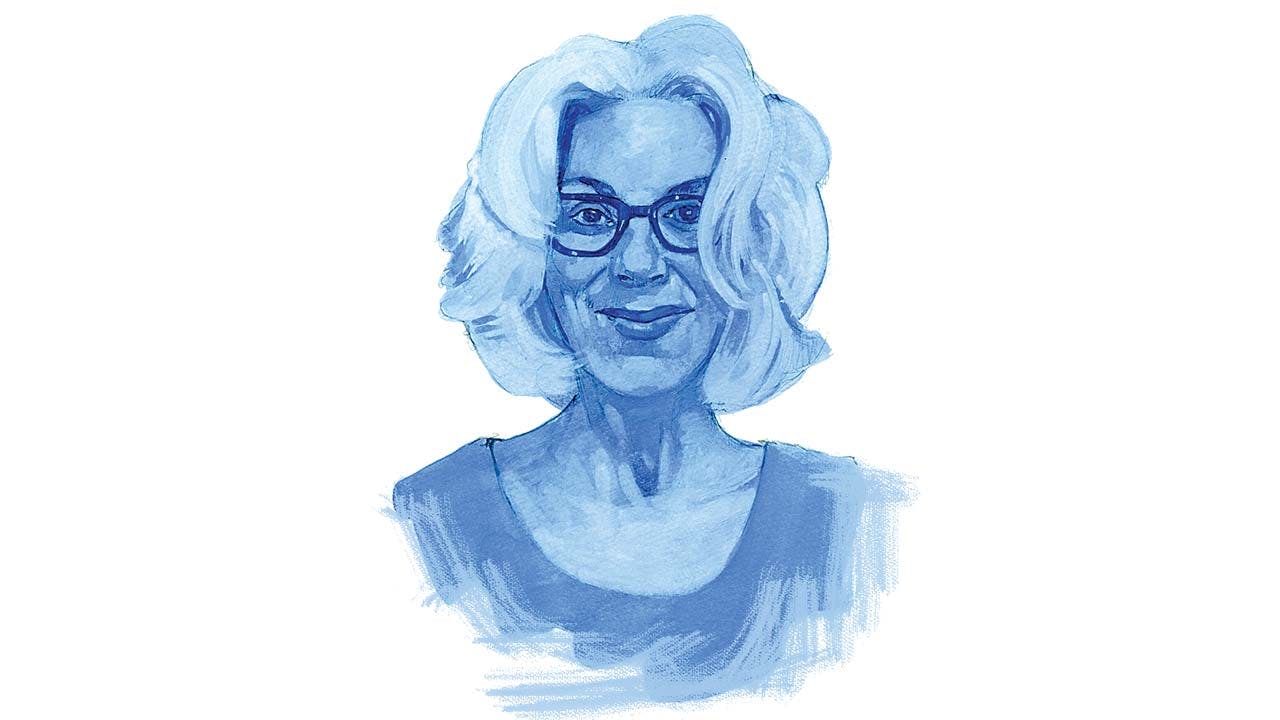

Merritt Tierce

One night in Dallas in March 2006, Merritt Tierce, an emotionally fragile, divorced young mother of two children, got into an argument with a former lover. Alone in her apartment, she burst into tears. Nearly overwhelmed with despair, she put a hot iron to her thighs. Then she drove to a coffee shop and opened her laptop.

Like a lot of people, Tierce had always wanted to be a writer, but she had never written anything except some college papers. That night, however, she decided to write a short story set in a fictionalized restaurant that was not unlike Nick and Sam’s, the high-end Dallas steakhouse where she was then working as a waitress. Among her characters were Sal and Danny, the restaurant’s owners, and customers ranging from sports stars to big-spending businessmen.

Mostly, however, Tierce wrote about a 21-year-old waitress named Marie, an emotionally fragile, divorced young mother who tried to deal with the pain in her life by cutting herself and self-medicating with drugs and constant sex with more than thirty men in the space of three months. “It wasn’t about pleasure,” Tierce wrote of Marie’s often brutal sexual encounters. “It was about how some kinds of pain make fine antidotes to others.”

When I recently met Tierce at a quiet restaurant in Denton, where she now lives, she didn’t strike me as the self-destructive type. Dressed in strappy white shoes and a sleeveless yellow dress, with her pretty, angular face framed by chunky glasses, the 36-year-old cheerfully told stories about her new husband, her teenage children, and her passion for gardening. “People look at me and say, ‘You’re the one who wrote that book about the waitress,’ ” she said, “and I reply, ‘Yeah, sometimes I have trouble believing it myself.’ ”

In fact, when she finished writing at the coffee shop, she had no expectation that her story, titled “Suck It,” would ever be published. “I assumed it wasn’t good enough,” she said. But she worked up the courage to show it to the Dallas writer Ben Fountain, whom she had met through a friend. At the time, Fountain was busy: his first book was about to be published, and he was working as the fiction editor of SMU’s literary journal, the Southwest Review. But he agreed to look at her story. “I found myself reading ‘Suck It’ every other day for two weeks, trying to figure out if it was really as good as I thought it was,” Fountain said. “And it was more than good. Her writing was totally unsentimental, at times outrageously hilarious, and at other times absolutely terrifying.”

Tierce had always been fiercely intelligent. In 1997, when she graduated from high school in Denton, she was named a National Merit scholar, which essentially meant she could attend any university she wanted. But because she was a devout Christian, she eventually chose Abilene Christian University. In her senior year of college, she was accepted into the Yale Divinity School. Then she discovered she was pregnant. “I had just written a paper for class affirming the biblical views against abortion,” she said. “There was no question I would have the baby—which in my family meant there was no question the baby’s father and I would have to get married.”

They returned to Denton, where Tierce worked as a secretary while her husband finished his undergraduate degree. She gave birth to their son in 2000, had a daughter a year later, and took a job waitressing at Chili’s. “We were poor, on food stamps and Medicaid,” she said. “And I was so miserable. I didn’t know what had happened to my life.”

Tierce began spiraling into depression. She cut and burned herself, split up with her husband, and briefly went into treatment. She kept waitressing, and in 2005 she was hired at Nick and Sam’s. The managers loved her: cool and imperturbable, she was assigned to wait on visiting celebrities like George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg, and Derek Jeter. Rush Limbaugh gave her a $2,000 tip—twice. “I was able to put on a good performance, playing the smart girl, making clever conversation with the customers,” she said. None of them had any idea that when her shift was over, she would do whatever she could to numb her self-loathing.

Fountain’s encouragement helped Tierce get her life back together. He published “Suck It” in the Southwest Review in 2007, and soon after, Tierce was accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she wrote more stories about Marie. Periodically, needing to bolster her income, she would return to Dallas to wait tables at Nick and Sam’s. After she left Iowa, in 2011, she went to work for a few years as the executive director of a Texas abortion-rights organization. She also got an agent, who told her she had enough material for a book. The prospect of having the book published worried her; she knew that people would regard it as a thinly disguised memoir. “But it was important to me to tell the truth, no matter how ugly,” she said.

In 2014 Doubleday published Love Me Back to high praise. The New York Times called it “a brilliant, devastating debut.” The attention from reviewers was heartening, but Tierce said that what makes her most proud is that “people who work in the service industry would come up to me and say, ‘You did it. This is my life. You nailed it.’ ”

And then there’s the response among Dallas’s well-heeled set, who have treated her book as a rich source of gossip, trying to match various characters with their real-life counterparts. “Who is the basketball player that the waitress had sex with?” they wonder. “Which church pastor won’t allow waiters to speak directly to him?”

One thing that has impressed many readers is that Tierce didn’t come up with a sugarcoated ending. Toward the end of the book, when Marie is asked about her philosophy of life, she says, “Don’t bitch. Just adapt. Nothing is going to go right and everything is going to be hard.”

The irony is that things are now going right for Tierce, who spends much of her time with her new husband, her two children, her stepdaughter, and their six pets. As far as she knows, her kids haven’t yet read the book, nor do they seem interested in doing so. “They see me as a boring and happy mom, which is the truth,” she said. “Today, I actually took two naps.”

Tierce did say that she’s worried about one thing: what to write next. She’s got an idea for a trilogy of novels—“which, knowing me, will take a decade to write, and I need to publish something soon, because we’ve got bills to pay and college tuitions coming up.” But she admits she doesn’t have another searing personal story to tell about herself—“absolutely nothing,” she said.

I asked her if she would ever go back to work at Nick and Sam’s, even part-time, to make some extra money. Tierce threw back her head and laughed. “No. All caps, NO,” she said. “It was a scene, a great Dallas scene, I’ll grant you that, but it was never my scene. I now like the quiet.”

She laughed again. “I really like the quiet.”

What Tierce Told the PEN American Center When It Asked Her for Five Words of Advice for Aspiring Novelists and Short-Story Writers: “Read write read write read.”

Stephen Graham Jones

My uncle Randall always had a book in his hand. He read in the car, he read at restaurants, he read when you were talking to him. He read lots of different things, but mostly it was Louis L’Amour’s westerns and contemporary thrillers. When I was twelve, Uncle Randall looked up long enough to see that I was a reader as well, so he walked me down his hall to a linen-closet door and opened it up onto a wall of paperbacks. There were books behind books, as deep in as I could reach. He told me to take three, and when I was done, bring them back and take three more.

This was before I discovered that Midland, the closest big town, had used bookstores and public libraries. (My hometown, Greenwood, had pretty much nothing.) Without my uncle letting me burn through his stash, I don’t think I would be a writer today. I might not have even made it past seventeen, and definitely never would have made it to Texas Tech. That was where writing found me.

I was sitting in class one day when two police officers showed up to take me to the university hospital. Uncle Randall had been airlifted to the burn center there after an accident, and I was the only family they could locate. Sitting in the waiting room for three days, with only a pen and a spiral notebook, I wrote my first story, about a girl in a coma who receives a visit from her dead boyfriend. When I got back to school, I turned it in and won an award for it, and my adviser said I should consider adding English to my philosophy major, which I quickly did.

As for Uncle Randall, he’s doing great now. His paperback collection isn’t around anymore, but those books are still in my head, and my heart, and my pen. Here are four that have stayed with me all these years.

To Tame a Land, Louis L’Amour

So I’m this Blackfeet kid—only Indian kid in my school, my county, my everywhere—reading pulp cowboy novels with titles like this. Like the land needed “taming.” But at twelve? This was gospel. This was history. And this novel was one that my uncle and I traded back and forth, read over and over. What fascinated me about it was that the hero was always pulling Plutarch from his saddlebag and hunkering down behind a boulder to read. Oh, I thought, cool people read. And ancient Greek stuff, at that. Six years after the first time I opened To Tame a Land, I was a philosophy major.

Conan the ___________, Robert Jordan

Yep, Robert Jordan, not Robert E. Howard, who was actually from Texas. Howard may have created Conan, but Jordan, later famous for his Wheel of Time fantasy series, wrote a bunch of Conan novels in the eighties. And that was the Conan—the Invincible, the Defender, the Unconquered—that I found in that closet. To me, Conan was Indian through and through: he used whatever tactics would help him win the fight, and he always barely got out with his skin intact.

Miami Massacre, Don Pendleton

There were dozens of books about the exploits of Mack Bolan, an Army vet turned Mafia antagonist, and I read exactly one of them. Bolan didn’t do it for me; I couldn’t squint enough to see Mack Bolan as an Indian. But out of respect for Uncle Randall, I always took one Bolan book, which I’d then return as if I’d read it, saying I was ready for more of that brand of adventure. And that wasn’t necessarily a lie; I burned through the many John D. MacDonald and Ian Fleming novels in my uncle’s collection. But Mack Bolan, he was my pretend friend. I “read” him so I could keep reading through that shelf.

Rendezvous With Rama, Arthur C. Clarke

I wouldn’t get to Philip K. Dick, Samuel Delany, and Ursula K. Le Guin for a decade yet, so Clarke was the one who took me to space. Rama is the only science fiction I remember from my uncle’s closet; it may have been there by accident. I don’t remember much about what actually happens in Rama, but I distinctly remember the experience of reading it, how my face went slack with wonder, numb with delight. This world Clarke was showing me, I wanted to go there, now. I still do.

Number of Books Published Since 2000: 22

Ito Romo

Atop the dining room table in Ito Romo’s bungalow in central San Antonio, there’s a handcrafted skull in a vitrine, meticulously bedecked with shiny black beans. Nearby, in another glass case, a miniature highway scene captures the moment when an eighteen-wheeler’s trailer door opens to reveal a pile of lifeless bodies. They’re reminders that long before Romo became a writer, he was an artist who drew and painted and made hauntingly autochthonous sculptures such as these.

Yet words always captivated Romo, who majored in English as an undergraduate at San Antonio’s St. Mary’s University. “I loved literature,” the 54-year-old Laredo native says. “But I never wrote creatively.” Instead, he spent much of the eighties as part of a group that birthed the vibrant art scene that continues to energize San Antonio. Still, he always felt an affinity between his work and literature, which he had never stopped reading and thinking about. “In my art, I was telling stories visually,” he says.

After moving to New York City in the late nineties, Romo began to feel a compulsion to write. “I felt an explosion of pent-up words and images and emotions, some bright and beautiful, others dark—and beautiful too,” he says. “I found another kind of brush I didn’t know I had: my pen.”

Romo’s first collection of stories, 2000’s El Puente/The Bridge, established him as a writer with a knack for evoking the mythic inner dramas of borderlands people. The book is terse and austere in its language, but there’s a sense of the fantastic about Romo’s story cycle; the Rio Grande itself appears as a character in many of the linked tales, and even turns blood red.

For all its daring, El Puente is full of subjects that flirt with Latino literary cliché: endearing old ladies and dying echoes of the folkloric. “That book’s like a fairy tale,” he explains. “It still has hope, and it’s a little whimsical.” Soon after its publication, though, Romo felt an urge to transform his work once again. “I wanted to kill the abuelita,” he says. “I wanted to kill the tortilla stories. I wanted to say, ‘All right, so Hispanic writers have had to pay their dues, have had to write the way others wanted us to write for such a long time. I’m not going to do that.’ ”

The apocalyptic foreboding of El Puente, which was soon borne out by the wave of narco-violence that overtook the region, comes into full flower in 2013’s story collection, The Border Is Burning. Thirteen years after his first book, Romo’s stories grew darker. Car crashes, houses on fire, furtive sexual trysts, tweaking crank heads trying to maintain control—this suite of Romo cuentitos evokes a world in which chaos is rampant, and the gyre of events is ever-widening, threatening to explode. Yet these stark vignettes nonetheless show great compassion for people who Romo says are usually dismissed as “villains, lepers, and murderers.”

For a man who deals with such bleak material, Romo describes his ambitions in surprisingly sanguine terms: “I just hope I can produce work that in one way or another, be it dark or be it light, speaks to respect, dignity, hope, peace, and love.”

Romo’s Next Book: A “mestizo vampire novel” that begins in Granada in the eighteenth century, moves through Mexico, and ends in New York City in 2043.

Marcus J. Guillory

Ti’ John, the protagonist of Marcus J. Guillory’s 2014 debut novel, Red Now and Laters, is, as Guillory acknowledges, a thinly veiled version of himself. Like Ti’ John, Guillory grew up in Houston’s South Park neighborhood, the son of Louisiana Creoles who moved to Texas for economic opportunity. And like Ti’ John, Guillory saw a lot of violence as a young man. But though Ti’ John’s story ends just as he heads off for the University of Pennsylvania, Guillory’s life got even more interesting after he left Houston. Following his college graduation, Guillory attended law school, wrote screenplays, and worked on Snoop Dogg’s “reality sitcom.” Today the 42-year-old writer splits his time between Seattle and L.A. Here’s what he’s been up to lately.

You Are Beautiful

“In the rural South, a lot of people go to these get-rich-quick seminars. This screenplay, a character study of four people from Kerrville who go to one, asks what happens when you put hope in people’s lives. I picked Kerrville because I got a ticket there in 1999. I was an entertainment lawyer in L.A., and the firm had just gotten me a brand-new Mercedes, and I wanted to go back home and show it off, because nobody in my family had ever had a European vehicle. So I’m on I-10, going 103 miles per hour—I had it coming—and this Kerrville officer, a big ol’ guy with a big ol’ red nose, pulls me over and gives me a ticket. On the trip back, I stopped at the Dairy Queen in Kerrville and just listened to people talking. So when I was thinking about this screenplay, I thought, ‘Let’s do Kerrville—it’s got some character, it’s got some history.’ ”

Trill

“This is a screenplay that follows the path of a young Houston rapper who blows up, but he has a secret: he’s illiterate. And then he loses his voice, and all of a sudden he has to learn how to read and write so he can show his lyrics to people. At some point I’m gonna get that made. Might be a good time now, given how Straight Outta Compton is doing.”

Trinidad-Senolia

“I’ve always played music, and a few years ago I started getting into electronic music. Then I met the L.A. radio DJ Garth Trinidad, and I asked him if he’d be interested in reciting my prose over dance music I’d composed. I took a pseudonym—“Mateo Senolia”—and we became Trinidad-Senolia. In 2012 we got a record deal with the house-music label Yoruba Records, and our first EP included Trinidad reciting a passage from Red Now and Laters. It was a huge hit in the Afro house scene around the world, and people started really getting into the lyrics. I got an email from a young South African who wrote down what he thought the lyrics were but wanted to check them. I was floored! This was exactly what I’d set out to do: turn listeners into readers.”

The Day Job

“I’m working as a counselor at a group home for incarcerated teens in Seattle. I teach them life skills, chaperone them, cook them breakfast every morning. They remind me of some of the kids I grew up with. Sometimes you try to figure out why kids are incarcerated, and 80 percent of the time I think maybe it’s because they’re hanging out with the wrong kids. But then you meet the parents and you really start to understand. Some of these parents should be locked up.”

The Unexpected Entry on the CV: Guillory is, apparently, the first American to ever write a produced screenplay for a Bollywood movie, 2009’s Karma, Confessions and Holi.

Mary Helen Specht and Nan Cuba

For two writers who are separated by a few decades in age, 36-year-old Mary Helen Specht and 68-year-old Nan Cuba have a surprising amount in common. Both were raised in smallish Texas cities (Specht in Abilene, Cuba in Temple) before settling in considerably larger Texas cities (Austin, San Antonio), where they both teach creative writing at Catholic universities (St. Edward’s, Our Lady of the Lake). Both also released acclaimed Texas-set debut novels in the past couple of years (Specht’s Migratory Animals recently received a rave from the New York Times Book Review; Cuba’s Body and Bread was labeled a “Riveting Read” by O, the Oprah Magazine); both cite the late Texas writer Katherine Anne Porter as a major influence; and both have had the honor of being chosen as Dobie Paisano fellows by the Texas Institute of Letters (Specht resided at the Paisano Ranch in 2008; Cuba begins her fellowship in February).

So it seemed only natural to have the two authors sit down and have a conversation about writing, teaching, and the legacy of Texas literature. And better still, to have them do so at Katherine Anne Porter’s childhood home, in Kyle, which is maintained by the Burdine Johnson Foundation and Texas State University and hosts a prestigious visiting-writers series. Below is an edited excerpt from their conversation, moderated by Texas Monthly senior editor Jeff Salamon.

Mary Helen Specht: Since we’re sitting in Katherine Anne Porter’s house, maybe we should start by talking about Porter, and about how being a Texas writer has influenced you—if you think of yourself as a Texas writer.

Nan Cuba: I do think of myself as a Texas writer, and I’m very proud of that, but it took a while to get there. When I first read Katherine Anne Porter’s stories, as an adult, I felt a deep connection, and she has been extremely influential in my own work. Not on purpose, but as I look at my work now, I can see it. In the first chapter of my book, Body and Bread, there is a very short scene that actually is the genesis of the whole book. I wrote it as a piece of flash fiction, and it became the novel. It’s reminiscent of Porter’s very famous story “The Grave,” but that was unintentional—it wasn’t until I went back and reread “The Grave” that I could see the parallels. But what was most striking was that Porter had based her story on an autobiographical experience with her own brother as a child, as I did in my novel. When I reread “The Grave” I saw that her brother’s name was Paul, and so was mine. And my brother committed suicide, so that was what drew me to write the story. I knew that “The Grave” had stayed in my subconscious very deeply, and at first I was alarmed, very alarmed. Because I didn’t know that that could happen, that you could end up writing something that was so reminiscent of another person’s work. But then I relaxed into it. And I’m fine.

MHS: There is so much about the book that is not like Porter’s work, especially the scenes where the characters are younger. And as they get older it’s about a changing Texas that Porter wasn’t around to see.

NC: At least one bookstore manager outside of Texas labeled Body and Bread as “regional.” And of course we’re resistant to that label: it means you have a limited audience. Which didn’t surprise me: I knew that I would have a limited audience, because I write literary fiction. So, to be literary and also regional, now you have, like, three people who are reading your book. I’m working on another book now, and it’s also set in Texas. I can’t help it. That’s what I do. And I’m fine with that. Has your work ever been called regional?

MHS: Maybe I don’t get that label as much because I write mostly about urban Texas. There certainly are sections of Migratory Animals that are based on the Paisano Ranch, where I lived for a while. When I got the Dobie, I had been living outside of Texas for a number of years, and I didn’t think I would ever come back. But I returned for that fellowship, and seven years later, I’m still here. It was interesting being at the ranch, because even though people think of Abilene as rural, it’s still a town. Most of the people I went to high school with were more likely to be in heavy metal bands than to be roping cows. So the Dobie ranch was a return to Texas but almost a return to this imaginative Texas that I wouldn’t say I’d ever fully lived in.

Generally, the thing that interests me the most is this sort of post-Western Texas, where there are still these myths and masculine stereotypes but the reality is very different. I feel like Larry McMurtry, who wrote that he had to read himself out of the culture before he could read himself back in. As a kid, I was more interested in reading Jane Eyre and the Beats. It wasn’t until I left Texas that I started appreciating, for example, Katherine Anne Porter. And of course I identified with her in the sense that she left Texas. She didn’t want to think of herself as a regional writer. But I would certainly say that her best and most complex work is about Texas. Texas certainly wants to claim her now. And I think she felt ambivalent about that.

NC: Yes, she did.

MHS: And I can relate to that. In my twenties, I felt really ambivalent about that connection. Only later, and now, am I starting to settle into all the things that are great about being a Texas writer.

NC: Larry McMurtry called Porter’s work, if I remember correctly, “powdery,” which is a great word. “Powdery” and inspired by her neuroses. That’s a very gendered description. Very gendered. But she’s one of the writers who inspired me the most.

Texas’s literary legacy is very rich, beginning with Cabeza de Vaca, who published the first Texas book, about his experience of living with the Indian tribes and was very complimentary about them, actually. The writers who have influenced me the most, other than Porter, are William Goyen and Tomas Rivera—wonderful writers whose work is very rich. And we have to mention J. Frank Dobie, who preserved the folk tales of our state. I’m very grateful for that, because I was raised in Temple, which is probably thought of as a rural area, though my family members who are still there will resist that. My friend Donley Watt, who’s also a writer, grew up in East Texas. Once, we were comparing stories about our hometowns, and I said, “Okay, Don, be honest, how would you describe Temple?” And he said, “Temple is a place that wishes it could be Waco.” [Laughs.] Well, okay, it’s a small town.

But it was a wonderful place to grow up. I grew up in a world where story was everywhere. Everyone knew how to do it. When the family got together, that’s what we did. Everybody has family myths, but these were rich.

There was a period of time where much of Texas writing was about the Alamo, or the Texas Rangers. Much of it glorified. McMurtry called it sentimental and thin. And there were a lot of men present.

MHS: Well, I think some of that has changed, or is starting to change. I mean, you know, you go to Barton Springs and you see the philosopher’s rock where there are those statues of J. Frank Dobie, Roy Bedichek, and Walter Prescott Webb. And, you know, I have been there with other Texas-born writers who don’t know who those people are.

And I always have known, in part because my parents are librarians and we’re very connected to Texas history and literature. When I got the Paisano fellowship my grandfather was dead but my mother gave me his copy of Dobie’s The Longhorns, which Dobie had signed with his brand. So I come from a family that does know about that, but I think a lot of people don’t know those writers, and in a sense, they have faded away, whereas people like Katherine Anne Porter and people who were coming from a different perspective are the ones that people are still reading even though at the time Porter may have been dismissed as neurotic. Also I feel like a lot of the hostility against her was based on the fact that they felt like she thought she was better than them, and maybe she did—and maybe she was.

NC: All of that is so true about her. She was hopeful that her collection, The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter, which eventually won the Pulitzer, would be a Texas Institute of Letters selection. Instead, J. Frank Dobie’s book won.

MHS: Again! So it’s no wonder that she didn’t really spend a lot of time in Texas after she was an adult. And I think that that’s maybe another reason I feel connected to her sometimes, like you were saying, I don’t really go into my work with a goal or with a message or with, you know, themes that I’m trying to explore. I follow characters. But certainly I can look after the fact and see that in almost all of my work, what underpins the main characters’ decisions or their challenges is a search for home. That sense of, can you find a home in a person? Or in work? Or can you escape where you come from? Do you want to escape where you come from? And I feel like Porter was also struggling with that.

NC: Some of my family members, who live in Temple, when they were reading my novel, they assumed a lot of it actually happened. All of it was made up. But the reason they’re confused is because the places are real. So they assume that what I’m describing happened.

MHS: I had a friend read an early draft of my novel, and she felt I had gone over the top with the Austin setting. Austin is easy to do that with because it has its own kind of myth happening right now—you know, the mustachioed hipster, and the food trucks, and the live music. And it’s easy—even though I live here—to stereotype, to create a caricature. And I had to start thinking about the other layers, the darker histories of geographic segregation that are part of Austin’s past. And the newer challenges of gentrification. Austin is one of the only major cities in America that’s hemorrhaging African Americans. Two of the characters in my novel are from Abilene, where I’m from, but those are really some of the only scenes that I’ve ever written that are set in Abilene that have gotten published. I’ve actually had a really hard time. I’ve written about lots of other parts of Texas, but Abilene’s really been a struggle for me.

And I think part of it is, is the kind of whole “fish in water” situation—can the fish see the water? Does it even know it’s in water? Even though I lived outside of Texas for a long time, and think I can look at my hometown with outsider eyes, I’ve really struggled to articulate it. And I’m continuing to struggle with how to use Abilene, not creating a caricature, not creating a stereotype of this conservative, small West Texas town.

NC: That’s what keeps us working, right? Those new challenges that constantly pop up. I understand what you’re saying. The reverse is true for me. In my novel, the town is not called Temple. It’s called Nugent. And that’s the name of the street I grew up on.

Jeff Salamon: Both of you teach. I’m curious, are most of your students from Texas?

NC: Yes.

MHS: I would say that a little over half my students are from Texas.

JS: Are these kids interested in writing about Texas? Do they think of themselves as Texas writers?

MHS: I teach undergraduates, so a lot of them are just kind of coming to this idea of what it is to be a writer, and what their own voice might be. And I often find that they begin with one of two opposite approaches. I have students who come in, and because of what they’ve read, maybe in high school, they think that to be a writer means you have to be writing about, like, New York City, for example. And a lot of them maybe have never been to New York City, and so many of them start writing these stories about places they don’t know anything about, based on their image or their stereotype of what it is to be a writer. And it might have nothing to do with their own experiences and nothing to do with Texas.

And then you have the other side of the coin. People who write so autobiographically they have a really hard time figuring out how to begin opening up their own experiences into the realm of fiction. So whatever end of the spectrum they’re on, I usually try to nudge them a little bit in the other direction. If they’re writing all about Paris, but they’ve never been to Paris, to maybe think about starting with scenes from their childhood. I also have assignments where I ask my students to go, to leave their phone at home and to ride a bus around the city without a friend, and just observe. Because, while they know that writing is about the imagination, they often don’t realize how much of it comes from that kind of reporter’s eye, that sense of taking in what’s around you.

NC: My experience with undergraduates has been very much the same. When they’re just beginning to write, they’re resistant to honoring their own personal experience and to try to mine that, and they’re wanting to impress, even though I tell them that no one will remember what they share in a workshop, that they should be focusing on what they’re learning regarding technique and craft.

Think of this. If you are a brand-new writer and never written anything before and you’re from the West Side of San Antonio, and you think you want to be known as a writer, the temptation is to follow the dictates of what you’ve been told you’re supposed to write about your culture. So your tendency then is to fall prey to those cultural myths and to try to emulate what you’ve been taught you’re supposed to be saying through your stories. So my job is to encourage them to be much more honest and brave about their own particular voices and their own particular experiences.

MHS: Though not everyone is going to get those particular experiences. Even though the publishing industry is shifting, it’s still very New York-centric. A friend of mine recently got her manuscript back from the copy editor at her publishing house in New York, and one passage mentioned breakfast tacos, and the copy editor wrote in the margins, “Tacos are not breakfast food. You need to change this.”

NC: Oh no!

MHS: When so much is filtered through New York or filtered through the Northeast or even the West Coast, I think it’s important for younger writers to realize that it’s okay to push back: “No, no. Actually we do eat breakfast tacos here. And we love them. And you would love them too. You should try one.”

JS: Do either of you have a sense of whether the New York publishing world is more receptive to writing about Texas than it might once have been? Are we no longer considered such a backwater, as we might have been a few decades ago?

MHS: Well, I think that there have been several books that have done really well, like Bret Anthony Johnston’s book about Corpus Christi, and Philipp Meyer’s The Son and Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. But I don’t think it was that long ago that Ben Moser wrote an article for maybe the Atlantic or Harper’s with this theme of Texas literature still being pretty thin. So I still think there is this kind of reputation of it not being a very serious literary landscape. Hopefully that is starting to change, although again if you look at the books that get a lot of the really big recognition—I mean, the three I mentioned are all by white men. Not that they’re not wonderful books, but maybe there’s still some work to be done in terms of getting the New York publishing industry to be aware of the richness of Texas literature.

NC: My agent and I have talked about this, that it seems like there are preconceived ideas about what Texas literature is about and how it’s going to be written. It’s assumed that it will be white and male—McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy, a hint of violence and some cattle rustling and—

MHS: Something big, something epic, something dramatic.

NC: Epic. That’s exactly right. McMurtry called Katherine Anne Porter’s work a product of her neuroses and you mentioned the fact that these male writers that we’ve mentioned, much of their work seems epic whereas the female writers have produced work that seems more personal, more introspective, and maybe that’s less valued.

JS: I have a sense that over the past ten years, a lot more significant literature about Texas is coming out. It used to be that lots of Texas writers didn’t write about Texas, but a lot more Texas writers are going, “You know what? I can write about this place.” Is that my imagination? And maybe one thing to talk about—and I don’t want to overload you here—is, if people are growing up unaware of Dobie and Webb and Bedichek, is that a terrible loss? Is it a minor loss?

MHS: I do feel like the scene is changing and is getting more vibrant and bigger. I mentioned before that I’d been living abroad and also in the Northeast for a number of years before I came back to Texas for the Dobie Paisano Fellowship, and I didn’t plan to stay after the fellowship finished. And one of the reasons I stayed was because of the writing community here. When I started the fellowship, writers would come up to me and be like “I’ve read your work”—which at that time never happened to me—and invited me to events and introduced me to other writers and helped me get jobs teaching at the community college. And not only was it much more vibrant than I had expected, but it was also warmer in the sense of people helping each other out. I think some of that might come with feeling like we’re outsiders here in Texas compared to the literary scene in New York, or even in Boston, where I had been living. And that’s one of the main reasons I stayed after the Dobie Paisano Fellowship: it didn’t feel like a backwater to me anymore. It does seem to be changing, becoming much more diverse and much more exciting.

NC: Yes. I was going to emphasize the diverse part because I do think it’s becoming much more diverse, and that is being celebrated, which was not true in the past. It is a community, and that has not always been true of writers who step up and want to interact with each other and support each other. That was one reason I founded the literary center in San Antonio, Gemini Ink; I wanted very much to be able to create that kind of a community, and I think it’s working.

MHS: I do want to be clear that not everyone in this community is writing about Texas, but I certainly don’t feel like people are eschewing it, maybe like they used to. Did I pronounce that correctly?

NC: Yes, you did, you did a fine job.

MHS: Being from West Texas, when I ended up in college around people much more worldly, I mispronounced a lot of words that I’d only read for many years and I’d never heard spoken, so I had this kind of complex about being up in front of my class and mispronouncing all of the French words. But as to the incendiary question about whether people are still reading Dobie, Bedichek and Webb, I definitely don’t think that people are as much.

NC: No, they’re not.

MHS: Whether or not that’s a bad thing is a tough question. That’s something I struggle with a lot when I create my syllabi. I think it’s very important for my students to be immersed in what’s happening in terms of contemporary fiction, but at the same time, you don’t really want to forget where that fiction comes from. So I wouldn’t say that those writers are not important and they’re not worth looking at, but I don’t know if I would say it’s an enormous tragedy either.

NC: I do think the preservation of the folk tales is important. There’s a celebration each year called Dobie Dichos, it’s an evening around the campfire where writers come and read something that they’ve selected of Dobie’s. And it’s a lot of fun, it really is, I have to say. I didn’t know what to expect, and when I went I enjoyed myself a lot. But at the same time, I think of Americo Peredes, whose novel took, I don’t know, twenty or thirty years to finally be published, and in that book there is a character who’s modeled after J. Frank Dobie, and he’s considered a racist.

MHS: Of course, I guess that connects to all that’s going on in the news with the Confederate statues at the University of Texas and schools named after Confederate generals and so forth, and that fight between history and the sense of giving these figures a little too much of a hallowed place that maybe they didn’t deserve.

JS: When your students write about Texas, what, if any, clichés do you see coming up that you have to dissuade them from indulging in?

MHS: I don’t really see it. What I do see is that often, when my students are writing things that are about Texas, they don’t think of them that way because their idea of Texas literature is, you know, Lonesome Dove. And so sometimes I have to be like, “Your piece about your neighborhood in East Austin or your story about the suburb in Plano where you grew up is part of this tradition of Texas literature.” In their heads, Texas literature is all cowboys and westerns and wranglers. And I don’t get very many of them wanting to do that kind of Texas writing, so I don’t actually see that on the page.

NC: I guess my experience is with Latino students, and the kind of stories they feel like they’re supposed to be telling; they’re trying to anticipate what the audience wants. If you think about it, tourists come to San Antonio all the time, and they want to experience the Hispanic culture, so what do they get? They get the mariachis, they get flamenco, which is wonderful, I mean it really is, but they don’t see much beyond that. So what I get sometimes from my students is a folksy kind of conversation around the table with the family about expected kinds of topics rather than digging deeper into what’s happening within the family. It’s light, it’s a little of what writers in Texas did for a long time and what McMurtry called sentimental, a romanticizing of what is actually happening. They’re afraid to tell the real story. They’re afraid not only will they be revealing something that’s difficult, that’s harsh, but at the same time it won’t be well received.

Many of my students, a lot of them are the first members of their families to go to school, so they’re very quiet. They are reluctant to even speak in class, and then to share very personal kinds of experiences or their impressions about the world, and to be honest about that and to go to places that are uncomfortable sometimes feels like a betrayal to the culture, and so they have to work on that.

JS: Texas is at this point a largely urban and suburban state, and those landscapes are looking more like cities and suburbs everywhere else in the country. If landscape informs literature so much, is our literature in danger of becoming less distinct?

MHS: I think that’s been going on for decades. Television and movies and this kind of broader American culture have transformed the way people grow up, in a much more kind of American way. They feel less regional, they don’t necessarily think of themselves as Texans the same way that maybe my father’s generation thought of themselves as Texan. And I think that that’s kind of sad, but I don’t know if there’s anything to be done to change that.

NC: Hmm, they don’t think of themselves as Texan. That’s so interesting.

MHS: Or at least as strongly.

NC: Well, I do think the world, is, as they say, getting smaller. I’m trying to think about my students, whether they would identify themselves as Texan. They’re resistant to that history of what it means to be a Texan because they’re working so hard to change that history.

MHS: Well, we live in a time where very few people end up dying in the same place that they were born, and I think that that just changes all literature.

NC: When you look at landscape, we still do have long stretches of open land, and I guess the label for it is hardscrabble. A friend from, say, Vermont would look at it and tell me it was ugly. But to me it’s not ugly at all, it has an astounding beauty to me, I really notice it. And when I’m asked to talk about why I think it’s beautiful, there’s something interesting about being raised in this landscape that sends you messages about being thorny and tough, and at the same time there’s this open sky and optimism and hope. It’s kind of a schmaltzy toughness, you know, it’s the two opposites that are brought together that somehow create the way I at least think about myself and my family and this world and this state.

MHS: I’m going to backtrack a little bit and say that maybe the way to look at this issue of Texans losing their sense of regional identity isn’t to say that we’re just going to become like everywhere else, but that, moving forward, we’re going to be more about that space between myth and expectation and reality. That sense of, even if you grew up in, say, Dallas, you still have this idea of Texas as a place—the hardscrabble landscape of cowboys, the open sky. And even if that’s not your experience, you know in some sense you’re writing your way out of those expectations, you’re writing into that place between the reality that you’ve lived, and the expectations that come with being a Texan, and I think that space is really still pretty interesting and hopefully will be for a while.

JS: Even though both of you live in big cities, you came from smaller towns, so I suspect that you’re a bit closer to these myths than a writer who grew up in Austin or San Antonio or Dallas or Houston?

MHS: Yeah, definitely. My parents were really a part of that. My dad wanted to name me Scooter Bill, which was the nickname of Ernest Tubb’s daughter. My mother put the kibosh on that. So I listened to a lot of old Texas music growing up. My parents were really steeped in that culture, so even though I may have rejected it for a lot of the time I lived there and only kind of later appreciated it, like many people, it was certainly the air I breathed growing up. And that’s not necessarily the case for a lot more urban people of my generation.

NC: I grew up listening to jazz, my parents were into jazz. But when you talk about listening to the radio, well, this is embarrassing to admit, I married my high school sweetheart, and we are still married. And his grandparents emigrated from the Czech Republic, and in Temple, which is a small town, his family lived on the other side of the railroad tracks, and our mothers had met twice—in a small town, they had met each other twice. When I would go to my husband’s—my boyfriend’s, then—home, it was as though I was in a foreign country. The whole culture was vivid there: Czech was the first language, he and his two brothers played multiple musical instruments, they all painted, they listened to opera on the radio, they listened to the Czech Melody Hour, this is what he grew up amid, and I did too. So when you think about what has affected you and made you a Texan, that is a big part of it for me, a big part of it.

MHS: Whereas when my dad tried to put me to bed at night, he couldn’t remember any of the good lullabies, so he would sing “There’s a Tear in My Beer” or “Walking the Floor Over You.”

NC: We used to visit my grandmother and we would sit on a swing outside her house and she would sing every Texas song she could think of: “Texas, Our Texas,” “Deep in the Heart of Texas” [Specht claps the distinctive four-beat rhythm to the latter song]—we went through all of them, absolutely. “This is who you are, Nan,” she was telling me. And that was the message over and over, you bet.

JS: As writers, do you think that small-town Texas and smaller cities like Abilene are still a rich resource that haven’t been fully tapped yet?

MHS: I keep trying to write about Abilene, because I think it’s fascinating, for a couple of different reasons. Though a lot of the smaller towns around it have started to fade, Abilene itself is big enough that it’s not really a dying town. And there was something interesting in going to school with some kids who would come in their boots and jeans, and other kids that were dressed like goth. The fact that all of that is coexisting in an unexpected way, I really haven’t seen a lot of that in literature. So I think that there are those kind of things to mine, the ways those places are changing.

NC: My answer to that is yes. I mean, I tried to do that in my book, which is set in Temple. I don’t know in small towns how much the idea of writing about your personal experience is taught or encouraged. We just need to have more writers who come from that world, from that environment, who are taught that their voices and their perspectives are valued and then expose them to ways to acquire the skills necessary to produce great writing.

MHS: I grew up in a place that everyone used to say had the most churches per capita of any place in the state, although I’m not sure if that actually was ever true. So there was a teacher at my school who had a partner who was going to come with us on a class trip, and everyone would refer to her partner as her husband even though she was obviously a woman. And a lot of that I think is starting to change, even in those small towns, and it’s really interesting to see them grapple with what’s happening socially, politically.

NC: And that has a heritage. I mean, I can think of two writers, William Goyen, whom I’ve mentioned, his book House of Breath is about feeling alienated in a small East Texas town and his sexual orientation, once you think about it, is omnipresent in that story. And John Rechy, who was of Mexican and Scottish descent, grew up in El Paso, and his work is about the disenfranchised, but primarily those who are gay. And these were published decades ago. So we do have a history of that in this state.

JS: Let me ask a 180-degree version of that last question. Are Texas writers today doing justice to the Texas urban experience? Houston is about to become the third-biggest city in the country, but there just aren’t that many worthwhile novels about Houston. There are books about Dallas—I think Dallas has this certain mystique because of the assassination, because of the Cowboys, because of the TV show, people are sort of fascinated by Dallas. And then there’s Austin, which is one of the biggest, fastest-growing cities in the country, but there aren’t that many great books about Austin either. Is an opportunity being missed?

MHS: Antonya Nelson has a few stories set in Houston, but I think you’re right, there’s not really the great, popular Houston novel in that sense, and it’s a fascinating place. It’s funny, because I actually thought about setting Migratory Animals in Houston, and I found it too complicated. It was hard, in part because Houston doesn’t have a really strong literary history in terms of latching on and then expanding on that. And I thought maybe it was just too big, there are so many different things going on there, it’s kind of like five cities in one. I felt like Austin would be basically easier for me to do, and so I moved the university where my characters met to Austin.

Sarah Bird has done a lot of satire in terms of parts of West Lake and those sorts of areas, and Bret Anthony Johnston has written about Corpus Christi, which is not really a huge town, but beyond that I think you’re right. I wonder if it even goes back to that worry that the cities are too much like other cities in other states, and feeling like it can be a little harder to bring to life.

But it’s definitely the part of Texas I feel more drawn to write about, and I’m guessing there will be more people of my generation who feel drawn to write those stories. So maybe that’s the future.

JS: So Nan begins her Dobie Paisano Fellowship in February. Mary, do you have any advice for her?

MHS: My first piece of advice would just be that you should probably invite me out to stay with you. The Dobie is a bittersweet gift, I found. Unlike almost every writing fellowship I’ve ever known, you’re by yourself, so it’s like 250 acres and you, which gives you this false sense of ownership. So then when they ask you to leave, you’re like, “What? This is my ranch!” Since I left, I feel like all the Paisano fellows after me are interlopers. That’s the downside. I was there at the same time you’re gonna be there, in the spring and summer, and so my second piece of advice is, definitely take advantage of the creek in the spring because it dried up a lot in the summer, but it was wonderful in the spring to swim. And watch out for the water moccasins. It was really a magical time for me; I’d just come back from being abroad and had a lot going on in my head that I needed to work through, and getting up really early and taking walks in the hopes of seeing a coyote or deer or wild turkeys was great. And there are all these books in the house that try to teach you how to look at the different scat on the grounds and decipher them. So I would attempt that, like, “Hmmm. I think this is . . .” I’m not sure I ever got really great about it, but scat—we definitely need to get that into a story. It would be titled “Scat.”

The other thing I found really helpful when I was there was I kept a notebook with all the little details of what I saw, and I’m really glad I did because later, when I decided to set parts of my novel there, I could go back through this notebook and I could see okay, it was May and here was the bird, and feeder, and so . . .

NC: So a piece of advice is to keep the notes of what I see. I will do that, I will do that.

MHS: They’ve also made it a little nicer than when I was there. There’s fancier leather couches. It’s funny, when I showed up there, they were like, “We’re so sorry that there’s a scratch here or whatever,” and I’d been living in these tiny apartments in the Northeast and living abroad, and so I was like, “This is the nicest place I’ve ever lived!” There was even a television, though it only had, like, three channels. Apparently a fellow before me buried the television in the yard because it was too distracting. I didn’t find the three channels that distracting because there weren’t a lot of good things on them. And there’s a big table that was built by A. C. Greene, who was one of the Paisano fellows, and he was also from Abilene, so I really loved working at that big table overlooking the porch and feeling like I was connected to my own literary tradition of Abilene.

NC: When I was growing up in Temple, we didn’t, of course, have all of the social media and all of the technology that we have now. We had two small movie theaters, that was it, one library. So there was not a lot of exposure to theater or museums and that kind of thing. And as a result, the children spent a lot of time using their own imagination to come up with things. There are very creative people who have come out of Temple, musicians and artists and writers. And I think that maybe one reason is because using your imagination was encouraged. Telling stories was encouraged. We were taught that it was a necessary part of living your life.

Lisa Sandlin

If you’ve never thought about Beaumont as a great setting for a murder mystery, that just shows a lack of imagination on your part. Everything a good writer needs for noir is there: the sticky air, the swampy landscape, the insular, one-industry town—devoted to the oil business, in this case—that gives birth to a cast of characters up and down the social spectrum. And to top it all off, reptiles, both real and metaphorical.

“I haven’t had a dramatic enough life to write a memoir, and I’m way past a coming-of-age novel,” Beaumont native Lisa Sandlin says, explaining how she came to write what may be the best whodunit ever set in her hometown. “And with a mystery you’re not stuck with only the plot; you can also engage with theme and a sense of place.”

In her debut novel, The Do-Right, out this month from El Paso’s Cinco Puntos Press, the 64-year-old Sandlin has established Texas’s easternmost city as a place that, like Los Angeles and New York, possesses a seemingly infinite number of dark secrets. The same is true of Sandlin’s main characters, Tom Phelan, a roughneck turned private eye, and his secretary, Delpha Wade, who is trying to begin her life again after serving time for killing one of the two men who brutally raped her. As their friendship and working relationship deepen, Phelan and Wade join forces to solve a handful of disappearances, all the while providing glimpse after glimpse of a Beaumont rich in nuance and complexity. “Beaumont has some dramatic history, along the lines of that saying about war: ‘months of boredom punctuated by moments of terror,’ ” Sandlin explains. “Only it’d be ‘years of ho-hum punctuated by amazing or desperate events.’ Like the Lucas gusher, or the racial strife at the shipyard during World War II that called down martial law.”

Sandlin comes naturally to her authority on all things Beaumont; her father was a chemical engineer for Mobil Oil. “Up close to the refineries, you had a huge sense of process,” she recalls. “Roaring, pipes, tanks, burning flares. At night they lit up like fairyland.”

She attributes her strong ear for dialogue to her grandparents, who hailed from East Texas and Mississippi. “They talked some music,” Sandlin says. Some of that apparently got handed down. “Listen to how you talk,” a close friend told her when she was thirty. “You should be a writer.” She sat down and immediately wrote a passage about two young girls, and was hooked. “Even if I failed at it, I was going to write,” she says. She didn’t fail at it, but for a while, as is the case with many women writers, life—she raised a child on her own and held down a series of uninspiring jobs—kept getting in the way. Her first book, a collection of short stories, wasn’t published until she was forty. These days, she lives in Omaha and teaches at the University of Nebraska’s Writer’s Workshop.

Still, Beaumont has remained her muse; right now, she’s 12,000 words into a sequel to The Do-Right. “I always knew I’d be back,” she says of Texas. Then again, maybe she never really left.

Sandlin’s Honors: An NEA Fellowship, an award from the Texas Institute of Letters for Best Book of Fiction, a Dobie Paisano Fellowship, a Violet Crown Award, a Pushcart Prize, a New Mexico Book Award, and the Christopher Hewitt Award for Fiction.

Manuel Gonzales

Growing up in Fort Worth and Plano, Manuel Gonzales read tons of fantasy and science fiction. Even as a UT–Austin undergraduate who was immersed in “literary” fiction, he never lost his taste for the fantastical.

Gonzales’s 2013 debut collection, The Miniature Wife, reflects that sensibility; each story creates a small, hermetically sealed world (a plane that has been circling Dallas for twenty years, a video game in which an avatar achieves self-awareness) that follows rules different from those of our own world. His first novel, The Regional Office Is Under Attack!, due out in April, is yet another hybrid of high and low, a book about a “coterie of super-powered female assassins [who protect] the globe from annihilation.”

One of the assassins, as it happens, is from Texas, a locale that shows up in much of Gonzales’s work. “It’s a landscape and people that I’m very comfortable with,” he told a book club two years ago. “Which makes it easier for me to create a scene, create a place that feels—to me, anyway—imaginable and believable.”

When he’s not working on his fiction, the 41-year-old Gonzales teaches creative writing at the University of Kentucky, in Lexington, where he and his wife, Sharon, and their children, Anabel and Dashiell, now live, and keeps up a regular stream on Twitter that is every bit as funny and odd as his stories.

@hrniles March 1, 2013

Oh. Right. I35 sucks. #upperlevel #lowerlevel #allthelevels #atx

@hrniles June 5, 2013

By my count babies outnumber adults on this plane. Almost none of them fit into the overhead compartments.

@hrniles August 31, 2013

Day 2, Operation Mommy’s in NY: made chocolate chip pancakes, cleaned kitchen, folded clothes. Ha. Just kidding. Kids are drunk; so am I.

@hrniles September 1, 2013

So weird that there’s no kids menu at the Yellow Rose. Guess its steak for the kids. #whereareallthefamilyfriendlystripclubs?

@hrniles September 23, 2013

Am currently on the most humid Newark Airport Express bus in all of time. We are cultivating our own ecosystem here.

@hrniles February 4, 2014

Hey, it’s officially February 4th! Paperbacks of THE MINIATURE WIFE are now available. People have been lining up since 6am! #noreally

@hrniles March 6, 2014

There are no bears in Texas. (Famous last words before we take our inaugural family camping trip.)

@hrniles April 8, 2014

Gate’s not closed yet and the woman next to me is already into the Sky Mall Magazine. Pace yourself, Lady. It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

@hrniles February 20, 2015

Shout out to the blue-haired young woman in the book signing line in Vegas who suggested I write fairy tale erotica. #booyah

@hrniles september 1, 2015

Oh hey! Kentucky has mosquitoes too! Did you know? Now you know! Not just Texas. Kentucky too. Yay! I sure did miss them.

Where Do Writers Get All Those Crazy Ideas? Gonzales was once inspired to write a zombie story by his experience as a high school teacher “surrounded by soul-crushing tenth graders.”