Our highest executive officer has long touted his record on economics, and rightly so (see the “Texas miracle”). But can he claim the same success in public health? Or criminal justice? Or higher ed? Here’s a look at his leadership in eight areas of public policy, letter grades included.

Criminal Justice

At first glance, Governor Perry is as tough on crime as they come. Not only has he signed off on more executions than any other governor in modern U.S. history (276 at last count), but he has also defended the right to use the death penalty in controversial cases, such as when he denied clemency in 2004 to Kelsey Patterson, a mentally ill man whom the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, in a rare move, had deemed worthy of mercy. When asked about capital punishment during a 2011 Republican presidential debate, Perry offered a full-throated endorsement. “If you come into our state and you kill one of our children, you kill a police officer, you’re involved with another crime and you kill one of our citizens, you will face the ultimate justice in the state of Texas, and that is, you will be executed.”

But take a closer look, and Perry’s views on criminal justice are more nuanced. A bill Perry signed in 2005 that allows juries in capital murder trials to consider life without the possibility of parole has dramatically reduced the number of people who are sentenced to death. (Jurors previously had to choose between death and life with parole, making them far likelier to pick the former.) The law has profoundly changed the future of capital punishment in a state that has had more executions than any other. In 2002, which was the high-water mark for death sentences during Perry’s tenure, 37 people were convicted and sent to death row. Last year, the number dropped to 9.

Criminal justice reform has never been one of Perry’s top priorities, but as members of his party became interested in recent years in curbing the ballooning cost of incarceration, Perry signed dozens of reform-minded bills. He authorized legislation that established drug courts around the state, which emphasize treatment for certain drug-addicted offenders rather than prison time, and diverted funds from prison construction to enhancing probation, parole, and treatment alternatives. The subsequent reduction in the number of inmates has resulted in the closure of three prisons—a radical departure from the days of Ann Richards and George W. Bush, who oversaw a massive prison buildup around the state. “I think Perry came to see that Texas was going to break the bank if it didn’t get smarter on criminal justice policy,” said Marc Levin, the director of the Center for Effective Justice at the Texas Public Policy Foundation. “Rather than spending money on building more prisons, he saw that we should be spending it on proven alternatives like mental health and substance abuse treatment.”

Though many people scratched their heads when Perry announced in January at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, that he supported the decriminalization of marijuana use, he had already acknowledged that he did not believe incarceration was always the best route for nonviolent offenders. Back in 2007, Perry signed legislation allowing police officers to issue citations instead of making arrests for certain misdemeanors, including marijuana possession. And back further still, in 2003, he supported a bill that mandated probation for first-time drug offenders caught with less than a gram of cocaine, heroin, or other hard drugs. While a more liberal-leaning governor might never have had the political capital to support such legislation—or many of the other issues that Perry signed off on, from sentencing reform to prison downsizing—Perry actually did. “Perry has used demagoguery about the death penalty as cover for being able to do some remarkable things,” observed Scott Henson, the editor of the criminal justice blog Grits for Breakfast. “As long as he’s pounding his fists over the death penalty, no one can portray him as being soft on crime.”

Perry and state senator Rodney Ellis at the signing of the Michael Morton Act, in 2013. (©Marjorie Kamys Cotera)

Because of a wave of DNA exonerations during Perry’s time in office and the efforts of state lawmakers to improve the system that had allowed such wrongful convictions to take place, Perry presided over a period in which Texas led the country in its efforts to improve police, forensic, and prosecutorial procedures. He signed into law legislation that improved and standardized the way law enforcement conducts lineups; mandated that the testimony of jailhouse informants be corroborated; required prosecutors to hand over exculpatory evidence to the defense (through the 2013 Michael Morton Act); guaranteed a defendant’s right to post-conviction DNA testing; substantially raised compensation for the wrongfully convicted; and established the Forensic Science Commission, which elevated the standards of state and local crime labs. Unfortunately, it was also in this arena that Perry had arguably the lowest moment of his governorship, when, in 2009, he successfully scuttled the Forensic Science Commission’s inquiry into whether or not a Texas man named Cameron Todd Willingham—who had been convicted using outmoded science and was later executed on Perry’s watch—had actually been innocent.

Given how relatively limited the governor’s influence is, except for veto power, how much credit does he deserve for the transformation of the state’s criminal justice system during his tenure? “Considering that Texas is a very conservative, Southern state, I’d say he’s been above average,” said state senator Rodney Ellis, a Houston Democrat who authored many of the bills Perry signed that sought to remedy police and prosecutorial misconduct. “He has not led on these issues, but he did not sabotage these bills either. He gets high ratings for not being an obstructionist.”

Former state representative Jerry Madden, a Republican from Richardson who helped lead the effort to downsize the Texas prison system, said, “To his credit, he got on board with us. He didn’t lead us into battle with his saber drawn—he basically said, ‘Why don’t you go on ahead?’—but he signed almost every bill we sent him.” At the end of the day, Madden noted, it would be difficult to find another governor in the country who has signed as much reform-minded legislation as Perry. “Some governors are sticking a toe in the water and finding it’s not as cold as they thought,” Madden said of criminal justice reform. “Perry didn’t just stick his toe in the water, he jumped.”

Quick stats:

Number of inmates sent to death row in 2002: 37

Number of inmates sent to death rol in 2013: 9

Transparency and Ethics

Rick Perry is probably not what Plato had in mind when he wrote that republics should be ruled by philosopher-kings. He has, as governor, been more honorable than many of his predecessors were and more ethical than many Texans would have insisted that their governor be. That’s not much of a compliment, though, considering his predecessors and the expectations in question. And so we can’t review the governor’s record on ethics and transparency without considering whether Texas is seriously committed to the same goals.

The good news first. Perry has taken an interest in transparency, at least as it relates to spending. He has signed a number of measures to make data about state and local finances available online, and the results have attracted national acclaim: Sunshine Week and the U.S. Public Interest Research Group have both ranked Texas at or near the top of all states for government transparency.

Those have been worthwhile reforms, although Perry’s leadership on the subject should come with a couple of asterisks. It’s true that before he was governor, the state didn’t put much spending data online, but that’s partly because he became governor in 2000, well before most Americans had computers in their pockets. And in pursuing financial transparency, Perry has seemingly been more concerned about efficiency than ethics. When he has touted transparency as an ethical imperative, it has seemed political, as in 2009, when he issued an executive order commanding strict accounting standards for the federal funds that Texas was due to receive under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. And then, at times, he has set transparency aside altogether, as last year, when he vetoed a “dark money” bill that would have required greater campaign finance disclosure.

Perry’s ethical lapses as governor mainly fall into two related categories: corruption and cronyism. He has packed state government with pals and asked them to do his bidding; he has disbursed billions of dollars in state money to private companies, some of which are owned by or affiliated with other pals. Complaints about these practices are reasonable. That is apparent from the disastrous executive order, which the Legislature overturned, requiring that young girls receive a new vaccine against cervical cancer; at the time, his former chief of staff, Mike Toomey, was working as a lobbyist for Merck, the pharmaceutical company that stood to benefit from the program. It’s also clear in the ongoing fallout over mismanagement at the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), which was created after the state’s voters approved up to $3 billion in funds for that purpose in 2007 and which is under investigation for disbursing multimillion-dollar grants without proper review or oversight.

But Perry’s hands-on management style is legal enough, at least in Texas. The state constitution gives the governor fairly broad latitude to appoint people, in keeping with that document’s Reconstruction-era ambivalence about government itself: those jobs are supposed to be so easy that anyone can do them. And Perry’s so-called slush funds—the Texas Enterprise Fund and the Texas Emerging Technology Fund—were both authorized by the Legislature, which has subsequently appropriated billions of dollars for them. Governors can get away with that kind of thing if the voters don’t hold them accountable, which Texans haven’t, perhaps for a reason.

It’s significant, too, that the most high-profile ethical scandal of Perry’s administration may turn out to be one of his least controversial actions. Last year, he used his line-item veto power to remove state funding from Travis County’s Public Integrity Unit. He had warned he would do so unless Rosemary Lehmberg, the district attorney, resigned. Democrats argued that the governor’s motive was political, that because the unit in question is dedicated to prosecuting government corruption—it is currently investigating the troubled CPRIT—Perry must be trying to sabotage it.

But the governor had never tried to sabotage the PIU before Lehmberg was arrested, two months earlier, for drunk driving. Her blood alcohol content, hours after the arrest, was nearly three times as high as the legal limit. Grainy video footage of her staggering through the field sobriety test and lashing out later that night at the jail corroborated that finding. She was sentenced to 45 days in jail but was allowed to leave early to enter rehab. In his veto statement, Perry said that the district attorney had “lost the public’s confidence.” That seemed plausible, given the circumstances.

Lehmberg remains in office, and Travis County ponied up some money to offset the state cuts, as Perry had predicted they might. In April, however, a grand jury was seated to consider whether Perry ought to be indicted for coercion, bribery, or abuse of power. Democrats felt vindicated. They shouldn’t have. Their effort to turn this, of all things, into an ethical scandal suggests a resilient truth about Texas politics. Ethics may be valued, but they are rarely prioritized over more pragmatic concerns, like economic development or partisan jostling. Perry may not have led the state in a more enlightened direction. Did Texans want him to, though?

Quick stat: Estimated amount of questionable CPRIT grants: $56.3 million.

The Environment

The litany of unpleasant facts about the state’s environment is a familiar one: Texas leads the nation in emissions of greenhouse gases and mercury. Houston and Dallas are among the smoggiest cities in the nation. Childhood asthma is reaching epidemic proportions in urban areas. Nineteen counties currently fail to meet federal air-quality standards.

It is worth pointing out that such tallies sometimes reflect a perplexing lack of context: Texas is a large and populous state, with lots of power plants and vehicles. We refine nearly a quarter of all the gasoline used in the country. If every state made its own gasoline and vinyl chloride instead of buying it from us, we’d be much farther down on some of these lists.

Alas, that is a pretty meager caveat compared with the reality that is our state’s environmental record. The truth is that Texas deserves its national reputation as a place where business comes first—and public health and environmental concerns come in a distant second. The budget of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state’s main regulator of industrial pollution, has been cut by 30 percent since 2008. At times, Governor Perry’s fight against environmental regulation seems almost like a point of state pride for him, as though the Alamo were an old revered coal plant. In 2009, when Lisa Jackson, the head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, announced that greenhouse gases would be regulated under the Clean Air Act, Texas was the only state that refused to comply. In fact, Texas sued the federal government. “This legal action is being taken to protect the Texas economy and the jobs that go with it, as well as defend Texas’s freedom to continue our successful environmental strategies free from federal overreach,” Perry said at a press conference in February 2010.

That was just one of eighteen suits Texas filed against the EPA during Perry’s tenure, a track record that seems aimed as much at garnering national support for his presidential ambitions—fighting off “Washington bureaucrats”—as it is at shoring up support from the industries that matter in Texas. Perry is nothing if not politically savvy, but he has at times seemed shockingly unaware of which way the wind was blowing on air pollution. In 2006 he issued an executive order directing the TCEQ to fast-track approval of new power plants. That paved the way for TXU (now known as Energy Future Holdings) to propose the construction of eleven coal-fired power plants, which are most associated with smog-producing ozone. The backlash came swiftly from prominent Republicans like real estate mogul Trammell Crow; Perry’s pro-industry instincts kept him from noticing that concern about air pollution had gone mainstream while he wasn’t looking. A state judge ruled that Perry had overstepped his authority, and TXU’s plan eventually died. It soon became evident that natural gas, which burns cleaner than coal, was the energy of the future in Texas, and TXU found itself struggling to keep open the coal plants it already owned—especially the old, heavily polluting East Texas plants that couldn’t meet new federal regulations.

Perry’s tenure has had some bright spots. His appointments to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission have generally been sound, and commissioners have found a good administrator in executive director Carter Smith, who has done his best to run an agency starved of cash by massive budget cuts after the 2008 recession. Texas has also become the nation’s leading producer of wind-powered electricity under Perry, though that process was set in motion under George W. Bush and continues to rely heavily on federal subsidies. Given the opportunity to usher in a similar revolution in solar energy in Texas, Perry and his appointees at the Public Utility Commission have largely sat idle.

The same cannot be said for Bryan Shaw, whom Perry appointed to the TCEQ in 2007 and who became its chairman in 2009. Shaw has been nothing if not hands-on in his role as the state’s putative environmental watchdog. A climate-change skeptic (like Perry himself), Shaw has at times made a mockery of his agency’s own permitting process, overruling staff decisions when industrial applicants come out on the losing side.

A pair of recent reports tells the story as well as any longer analysis could. The official position of the TCEQ is that increased oil and gas drilling in the Eagle Ford Shale and elsewhere in the state has had no significant impact on air pollution in Texas cities. A San Antonio–area planning organization studying the issue with a grant from the TCEQ found otherwise—and had the temerity to announce those findings to the press before sharing them with the TCEQ. The agency’s response? Freeze the group’s funding.

More recently, TCEQ staff raised eyebrows by joining oil and gas industry officials in publicly attacking a peer-reviewed University of California study linking long-term exposure to ozone with an increased chance of early death. The EPA was collecting comments on a proposed new rule to tighten ozone standards nationwide, most of which, predictably, were from the industries most affected by the change. Among them was this statement from TCEQ executive director Richard A. Hyde: “The available evidence does not support a consistent association between ozone exposure and mortality.” As the Dallas Morning News pointed out, Hyde was the only state environmental official in the nation to question the link; it was like a game of “one of these things is not like the other.”

After years of finding himself steamrolled by Shaw, former TCEQ commissioner Larry Soward became an outspoken critic of the agency’s decision-making during Perry’s tenure, despite having been a Perry appointee. He was asked during Perry’s 2012 presidential run how the EPA would be affected if Perry reached the White House. Soward replied, “Just look at the TCEQ.” For a state that prides itself on its connection to the land and its wide-open spaces, Texas deserves better.

Quick stat:

Change in the TCEQ budget since 2008: -30%

Economic Development

Texas’s economy was already performing relatively well at the time Rick Perry became governor. Exports, for example, were flourishing as a result of NAFTA. He would also, as it turned out, have the good fortune to govern during the period of technological innovation that enabled the shale boom. And the heart of the Texas model, which he invokes in promoting the state’s business-friendly climate—limited government and low taxes—predates him by more than a century.

In terms of economic development, then, the governor hit the ground running. In retrospect, though, the fact that Perry has presided over the “Texas miracle” has to be more than a coincidence. Jobs and the economy have been his long-standing preoccupations. As ag commissioner, he called for the state to support agriculture processing businesses by issuing loans from a dedicated fund. “We’re exporting dollars,” he said in 1991. “We’re exporting the ability for a young person in Texas to have a good job.” Then as now, no industry was too tiny, or too unpromising, to win his support. In 1992 he penned a letter to the Houston Chronicle explaining how the Department of Agriculture was trying to support the state’s wine industry. “It’s not a novelty anymore,” he said—a wildly optimistic comment at the time.

As governor, Perry’s focus on business has led him to make sweeping concessions to the private sector. He has kept taxes and spending low, and he signed tort reform laws in 2003 and 2005. But he has also supported investments in public goods like roads and water—the types of investments in infrastructure that benefit the people of Texas as well as its businesses and should not be controversial in a rapidly growing state, even among fiscal conservatives. And at times Perry has taken a more direct role in job creation. In 2003 and 2005 he also signed legislation creating the Texas Enterprise Fund and the Texas Emerging Technology Fund, respectively. These “deal-closing funds,” as the governor’s office calls them, have put billions of dollars at Perry’s disposal, which he has used to woo businesses to Texas, specifically in clusters tipped for growth, like manufacturing and biotech.

Critics argue that Perry has been corrupt in his practices, happily dipping into the state “slush funds” to support his cronies and effectively auctioning off Texas’s resources at fire-sale prices. It is certainly the case that he has offered incentives that didn’t pan out and that some of the industries that have flowered in Texas are weeds. Such criticisms, though, slightly misread his motives. Perry has supported renewable energy as well as oil and gas; he’s offered plenty of incentives to companies run by perfect strangers. A more apt analysis is that he’s been somewhat indiscriminate in his efforts, like a Hungry Hungry Hippo. Although he’s highlighted certain industries, he’s been open to almost all of them. If there were a job stuck in a tree outside Texarkana, he would probably mobilize the National Guard to coax it back to safety.

The results have been conclusive. Since 2000, Texas has grown by about six million people, and the workforce has grown by about two million. The state’s economy has largely kept up. Almost two million jobs have been added in the same span, and total economic output has grown. The Texas miracle of economic growth and job creation has rightly attracted national acclaim, but the awards and honors matter less than what this has meant for the people who live here. The state’s unemployment rate has been lower than the national average every month since February 2007. There has been job growth in every major industry, in every income quartile, and in every region of the state. And this has happened during a time when the national economy has been flailing. Texas is the only large state where the middle class is still growing.

There is, however, little room for complacency going forward. Texas’s poverty rate is still too high, although it is not much worse than the national average. The wealth of the people, as measured by things like median household savings and access to banks, is well below the national norm, even though Texas has largely caught up to the nation in terms of most income indicators. And growth has exacerbated some old challenges. Our newly diversified economy will require a more educated workforce than we currently have, and Texas will not sustain its prosperity without better roads and reliable water supplies. But a diversified and thriving Texas has the capacity to address those challenges. Perry deserves real praise for that.

Quick stats:

Texas unemployment rate in March 2010: 8.2%

National unemployment rate in March 2010: 9.9%

Texas unemployment rate in March 2014: 5.5%

National unemployment rate in March 2014: 6.7%

Public Education

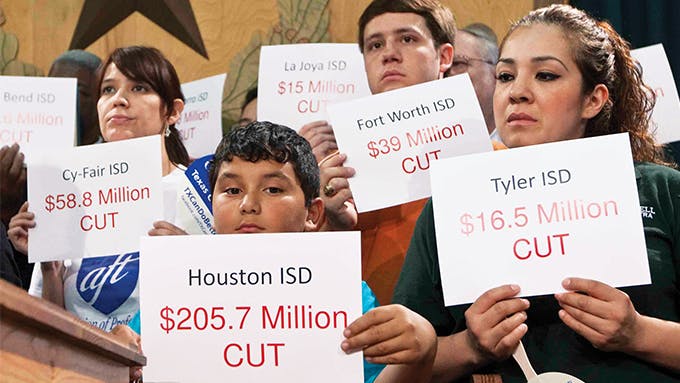

State leaders face no greater challenge than a budget shortfall, and the hole left in the budget by the Great Recession was one for the ages: $27 billion at the beginning of the 2011 session. With a new Republican super-majority in the House, tax increases and other forms of revenue were out, so massive cuts were inevitable. As one of the biggest pieces of the budget pie, public education was a fat target. Still, there was some good news: the state had roughly $6 billion available in the Rainy Day Fund, which is set aside for a crisis. By nearly anyone’s standard, it was definitely pouring in Texas. But the governor insisted that it wasn’t.

Already an undeclared candidate for the 2012 Republican presidential primary, Governor Perry saw a political opportunity where others saw a public policy emergency. He announced that he wouldn’t sign a budget that used the Rainy Day Fund, arguing that the money should be reserved for true emergencies, like natural disasters. This was an unexpected argument coming from Perry, who had signed off on budgets in the past that had all but liquidated the fund. Now, however, he insisted that legislators close the gap by cutting spending to the bone.

And they did. Legislators slashed funding for the 2012–2013 public education budget by $5.4 billion. For the first time since World War II, the state failed to fund enrollment growth in Texas schools. The effects were immediate. Ten thousand teaching positions were eliminated. State law requires a ratio of 22 students to 1 teacher in the early grades, but districts increasingly found that standard impossible to meet. The number of schools receiving waivers from that requirement tripled between 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

The cuts were unpopular, especially in rural and suburban districts, many of which are represented by Republicans. This perhaps helps explain the steady stream of obfuscation that has flowed from Perry’s office over the significance of the cuts, which continues to this day. Perry told reporters at a press conference last year, for example, that state spending on public schools grew at three times the rate of the enrollment increase between 2002 and 2012. But this is true only if you fail to adjust for inflation—a particularly facile gimmick—or account for the tax swap of 2006, which shifted some of the local funding of schools over to the state. The truth is that state aid declined by 25 percent during that period. Texas now ranks forty-seventh in the nation in spending per pupil.

Texas adds around 80,000 school-age kids annually, so nothing is more important than a well-funded public education system. And ours is an increasingly difficult population to educate. Statewide, roughly 16 percent of kids in public schools are not fluent in English, and the problem is more acute in urban areas: in Dallas, one in three public school students is not fluent.

How have the schools been performing under Perry? There have been a few encouraging signs. The graduation rate seems to be improving. Perry likes to tout a recent assessment that found that Texas has the fourth-highest rate in the nation, with 86 percent of our kids graduating. But these figures should be taken with a grain of salt. Another ranking that came out at about the same time used a different methodology and found that Texas was in the middle of the pack, at 79 percent. For Hispanic students, who now make up the majority of public school enrollment in Texas, the dropout rate remains scandalously high—33 percent by one measure. Researchers chalk that up to a variety of factors, but a lack of commitment to quality bilingual education in Texas is at the top of almost every list. Perry has been largely silent on that subject.

In general, scores on state-administered standardized tests gradually improved during Perry’s tenure, at least until the state changed to a new testing regime (known as STAAR) in 2012. But many experts believe that such trends have less to do with mastery of the content than with students’ and teachers’ growing familiarity with a given test. More tellingly, Texas has not fared well on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP. Between 2002 and 2013, we fell eleven spots in the nationwide ranking for both fourth-grade and eighth-grade reading. In 2000 our fourth graders’ math scores ranked seventh out of 41 states, plus the District of Columbia. By 2013, when all 50 states plus the District of Columbia were tested, we had fallen all the way to twenty-sixth. It is true that black and Hispanic students in Texas have outscored those in New York and California in both fourth grade and eighth grade, the two grades in which the NAEP is administered. But these scores have to be taken with a healthy dose of salt as well. Texas exempts students—citing language deficiencies or cognitive disabilities—from taking the NAEP at a much higher rate than any other large state (on the fourth-grade reading test, for example, Texas’s exemption rate was twice the national average). There has been no improvement on SAT scores during the Perry era.

And how about those STAAR tests? Perry is a dyed-in-the-wool proponent of high-stakes testing, and he seems to have been caught unawares by just how despised the tests had become. A simmering grassroots rebellion finally boiled over in 2012, when a group of suburban parents demanded relief from the testing regime. With Perry’s support, legislators in recent years had increased the number of tests needed to graduate from four to fifteen—higher than any other state. More than 80 percent of school boards signed a resolution opposing high-stakes testing, and prominent Republican legislators were insisting on changes. Having resisted efforts for years to scale back the program, Perry was finally forced to capitulate in the 2013 session, though House leaders worried about a veto up until the last minute.

The governor proved that he could learn a lesson. No doubt our children could do the same, if we gave them the chance.

Quick stats:

National ranking of Texas fourth graders in math on the NAEP in 2000: 7th

In 2013: 26th

National ranking of Texas fourth graders in reading on the NAEP in 2002: 29th

In 2013: 40th

Higher Education

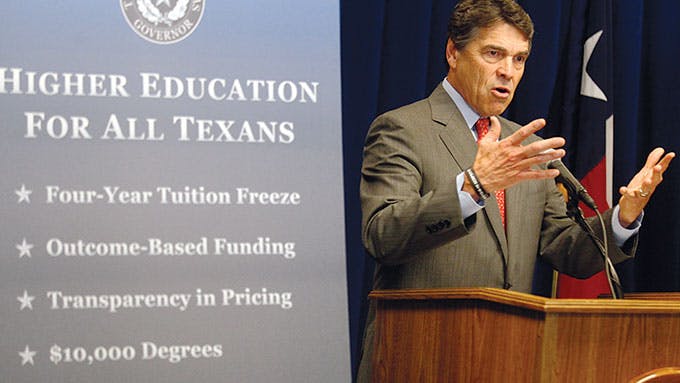

John Connally is remembered for his investments in higher education in the sixties that helped Texas businesses move into the high-tech age. George W. Bush signed HB 588 in 1997, which increased minority enrollment at the state’s public universities by guaranteeing admission for the top 10 percent of Texas’s high school students. And Rick Perry will be remembered for a 2003 law that forever changed the landscape of higher-education funding: tuition deregulation.

That issue proved the wisdom of one of the most famous sayings around the Capitol: policy doesn’t drive the budget; the budget drives policy. Faced with a $10 billion shortfall that session, lawmakers set about closing the gap in general revenue without raising taxes or finding additional revenue, so the ax came down on health and human services and higher education. For the first time in its history, the Legislature stopped its practice of setting tuition rates for the state’s public universities and allowed the boards of regents to take over that responsibility. The idea was to empower the universities to drive their own revenue, which would allow the state to lower its appropriations. Democrats fumed that changing the long-standing commitment to funding higher education would make it harder for individual families to bear the brunt of the costs. Republicans, with an eye toward fiscal restraint, complained that the law actually made the situation worse, which was echoed by a report from the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation in 2010. It concluded that deregulation “reduced the incentive for Texas universities to keep spending under control, shifted some higher education costs from taxpayers to students, exposed the lack of price competition in higher education, [and has] not significantly reduced the long-term pressure on state appropriations for higher education.”

For example, tuition revenue at the state’s public universities increased by 89 percent between 2004 and 2009, but state revenue, despite an initial decline after the law’s passage, grew by 25 percent during that same period. What did that mean to the average family? Well, the average full-time undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin, for example, would have paid $2,721 in tuition and fees in the fall of 2001 ($3,579 when adjusted for inflation), during the year of Perry’s first legislative session as governor. By 2013 that had jumped to $4,899. By comparison, the expenditures for the UT System, the largest in the state, jumped from $6 billion in 2001 to $14.6 billion in 2013. (Over that time frame, UT System enrollment jumped by 33.9 percent, and at UT-Austin, the flagship campus, the four-year graduation rate increased from 36.4 percent to 50.8 percent.) The question is, Is that money getting the best return on its investment? And did Texas work hard enough to make college accessible, considering that only one in five of today’s eighth graders is expected to earn a degree or certificate? “We’re not having an open conversation about who should be paying for higher education,” says Leslie Helmcamp, a policy analyst at the left-leaning Center for Public Policy Priorities, “and what we need to be doing as a state to create better jobs.”

As it turns out, Perry did try to have that conversation, in the form of the Seven Breakthrough Solutions, which were presented at the Stephen F. Austin Hotel, in Austin, to the regents of the various university systems in the state in 2008. The ideas, which were closely associated with the work of the TPPF, were designed to address concerns that universities are inefficient and that the market should help determine costs. “I was at the meeting,” says former UT regents chair Charles Miller, “and there had been no previous discussions with the regents. You simply cannot provide the solutions before you identify the problems. Most of the ideas were so weak they died their own death.” Texas A&M tried to implement some of the ideas—the infamous red-and-black report measured professors’ performance based on how their salary, benefits, teaching load, and research affected the university’s bottom line—before abandoning them; UT resisted to the end. But that battle is part of the current war with the UT System Board of Regents. At press time, regent Wallace Hall was facing impeachment charges for massive information requests from the university in an attempt to seek out financial irregularities and abuses of power. Outsiders have seen his actions as a divisive attempt to remake the university and force the departure of UT’s president, landing the school in the headlines for all the wrong reasons. As the hearings against Hall drag on, there is little doubt that the publicity has hurt the school’s reputation and damaged its chance to hire top talent, including in the position for chancellor, which is currently open.

Another signature bill from the Perry era is one that made Texas the first state in the country to adopt in-state tuition for undocumented immigrant students, in 2001. “Perry was the leader on that issue,” Miller says. “There was no hesitation in his mind that it was the right thing to do, and he took a hard hit from national Republicans, who turned it into something almost evil, which was too bad.” But despite its broad support in Texas, that law may also be up for reconsideration—Dan Patrick, the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor, has said that he wants to end the practice if he is elected this November.

Quick stats:

Average tuition and fees for a freshman at UT-Austin in fall 2001 (adjusted for inflation): $3,579

Average tuition and fees for a freshman at UT-Austin in fall 2013: $4,899

Public Health

It’s hard to evaluate the status of Texas health care without getting into the politics of abortion, birth control, the size of the fiscal debt, party polarization, and a host of other issues—and we have Rick Perry to thank for that. With our population soaring—including expensive young Texans and even more expensive old Texans—Perry has used the well-being of our populace to exploit partisan rage. And, not coincidentally, boost his own presidential ambitions. Needless to say, people who run public hospitals and charitable organizations, along with a statistician or two, do not think highly of his policies.

“Policies” is not actually the right word, since the governor really hasn’t had much of a public health plan since taking office—except to get the state out of as much federal oversight as possible. Oh, sure, at the beginning of his tenure Perry had some capable people in charge, but they melted away faster than an ice cream cone in August. Hence, public hospitals and clinics are currently strained to the max, and 25 percent of Texans—6 million people, just slightly less than the population of the Houston metropolitan area—lack any sort of safety net, which means that they have no insurance and go without physicals, mammograms, inoculations, and the like. When and if they finally get care, it is typically only because they have reached a crisis, the treatment for which is likely to be very expensive but not very effective.

Perry’s values reflect one hearty strain of Texas tradition, the one that has never been too sympathetic to the poor and downtrodden. The same could be true of his calls for fiscal responsibility on the part of the state and federal government—his assertion that we simply cannot afford to spend vast amounts on public health. Those notions might have sold well when Texas was an underpopulated rural state, but they’ve now brought modern, urban Texas to the brink. As former state demographer Steve H. Murdock and his co-authors note in Changing Texas: Implications of Addressing or Ignoring the Texas Challenge, “Texas’ population is projected to increase by more than 30.1 million people from 2010 to 2050, an increase of 119.5 percent to a total population of 55.2 million people. . . . The number of incidences of disease and disorders in Texas will increase even more rapidly, with the number of incidences increasing by 84.3 million, or 136.8 percent, from 2010 to 2050.”

While these numbers were bearing down on the state before Perry became governor, he has done little to address them while in office. Yes, we have a new medical school in Austin, and yes, we have a chance of getting new doctors to ameliorate the shortage here. Yes, in 2007 he mandated that Texas’s teenage girls be vaccinated against HPV, a virus that causes cervical cancer, though critics suggested this was due to Perry’s right-hand man, Mike Toomey, who went to work for Merck, the developer of the vaccine and a generous contributor to the governor’s campaigns. Meanwhile, he hasn’t supported improvements in workplace safety, such as a ban on indoor smoking. He did, however, favor a law to reduce taxes on chewing tobacco. The list goes on: He vetoed a law to ban texting while driving and has worked overtime to prevent the dissemination of birth control and sex education in the schools. Merciless cuts to programs for the neediest Texans started in the 2003 session and have continued apace for the rest of his term. Women and children situated well below the poverty line are his most frequent victims. There was, for instance, the devastation of the Children’s Health Insurance Plan eleven years ago, which left at least 150,000 children uninsured. Perry made Planned Parenthood public enemy number one, and as a result, access to safe and legal abortions in Texas—along with information and birth control that would prevent them—is becoming a thing of the past. At the same time, he has claimed that Texas has some of the finest health care in the country—meaning that we can find just what we need in emergency rooms all over the state. Ignoring the cost involved, Perry stated that Texans “for decades have decided that this is the way we’re going to deliver health care.”

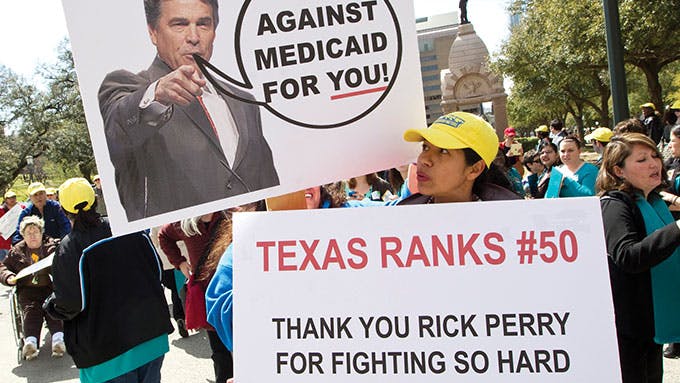

But by far the worst move Perry made was turning down the expansion of Medicaid that is a part of the Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare. In short, he has refused $100 billion over ten years in federal Medicaid funds to help the uninsured get the health care they need, with the federal government paying 90 percent of the costs going forward. As former lieutenant governor Bill Hobby said, “Of all Rick Perry’s inexplicable antics as governor, none is as puzzling and tragic as his refusal to allow Texans to benefit from the Affordable Care Act. Millions of needy Texans suffer because Perry has refused to participate.” Hobby goes on to say that, because of Perry’s refusal, Texans’ tax dollars will go toward funding the program in other states.

It would be one thing if Perry’s belief in fiscal conservatism could be supported—if it were true that, as he has claimed, the ACA was expanding “a broken system that is already financially unsustainable.” In fact, as the pro-expansion forces have noted, taking the money makes a lot more sense than refusing it. For example, a report by the economists at the Waco-based Perryman Group concluded, “The state actually makes money by participating in the Medicaid expansion.” Among other things, accepting the federal funds would create jobs and ensure healthier, more productive workers. Of course, taking the money will also save lives. Let’s hope those factors figure into the next governor’s agenda.

Quick stats:

Texas’s ranking among the states in uninsured residents in 2003: 1

Texas’s ranking among the states in uninsured residents in 2014: 1

Transportation

Rick Perry has repeatedly sought to address transportation in Texas during his time as governor, but there is no other issue on which he has been so reliably thwarted. Next time you’re stuck in a traffic jam, pat yourself on the back. The transportation system we have in Texas today may not be good, but it’s exactly what we’ve asked for as voters.

The problems—the sprawling congestion, the crumbling highways—were all predicted. They were also predictable, given the various trends over the past ten or fifteen years: the soaring population, the growth in industries such as energy and manufacturing, the stagnant revenue streams, the political torpor. According to the Texas Department of Transportation, over the past 25 years, Texas’s population has grown by 57 percent, and overall road use has nearly doubled. State road capacity, however, has grown by only 8 percent during that time.

Perry has called for greater investment in infrastructure since his first year as governor, when he signed a measure designed to create the Texas Mobility Fund, which had the authority to issue bonds for highway construction and other transportation projects. It marked a conceptual departure from Texas’s long-standing pay-as-you-go approach to road funding, and voters approved the constitutional amendment in November 2001. Two months later Perry unveiled his master plan. The Trans-Texas Corridor called for the construction of four thousand new miles of toll roads, with high-speed rail, oil and gas pipelines, and utility lines running alongside them. All told, the project would cost about $175 billion. “Nothing is too big for Texas,” he said, “when economic security and quality of life are at stake.”

Republicans and Democrats alike disagreed. They complained about the fees Texans would pay on toll roads, the expansion of state debt, the unprecedented use of eminent domain, and the prospect that a foreign company like Cintra—a Spanish toll road operator—would stand to profit. Faced with the most sustained backlash of his career, Perry amended his hopes for the TTC, scaling them back many times before 2009, when TxDOT quietly abandoned the idea in favor of a more modest, incremental approach. In retrospect, it was true that there were things to dislike about Perry’s sprawling vision for the TTC. On the other hand, it was better than no vision at all, which is effectively what the governor’s critics were proposing as a counteroffer—and which is what we have now.

Since that setback, Perry has narrowed his efforts to focus on transportation funding. He has supported some reasonable proposals, such as ending diversions from the state highway fund. He has also supported some creative responses, such as a measure passed during special session last summer that will, if voters approve a constitutional amendment to this effect in November, allocate a portion of future revenues heading toward the Rainy Day Fund to a different bucket of money dedicated to transportation projects. The amendment is worth supporting, but it won’t solve the funding problem. TxDOT has said that it needs about $4 billion a year just to “maintain current levels of congestion,” and the measure would bring in less than a quarter of that.

Perry’s preference, over the course of last year’s session, was for the state to take on more debt to build roads. That’s not a terrible idea on its face; as the governor has noted, interest rates are low, and Texas’s growth is expected to continue. At the same time, there are reasons to be skeptical about borrowing. Drew Darby, a Republican representative from San Angelo, mentioned one last session during a floor debate: the state has borrowed $17 billion for roads since 2001, and it will ultimately cost $32 billion to retire that debt. As an alternative, Darby suggested raising the vehicle registration fee for the first time since 1985. That proposal went nowhere after Perry threatened to veto it. The governor has also dismissed the idea of raising the gas tax, which currently stands at 20 cents a gallon. That’s the thirty-eighth-lowest rate in the country, according to the Tax Foundation, and it hasn’t changed since 1991. Hiking it wouldn’t be a long-term solution, because cars are becoming more fuel-efficient, but by the same token, it wouldn’t be a crushing blow to Texas’s consumers either.

Then, too, it’s worth noting that investing in transportation infrastructure shouldn’t be such a hard sell. Left to his own devices, Perry would surely have done more for roads, as he has for economic development, and he deserves credit for championing this issue when so many ankle-biters have scoffed at him for trying. But transportation infrastructure, in a state this size, is not an issue that can be adequately addressed via an executive officer, however ambitious. In a 2001 editorial, the Dallas Morning News noted that the new governor had done well in some respects but suggested that Perry might learn from George W. Bush’s more engaged approach to the Lege: “More stroking here or there could have yielded greater progress on such issues as transportation.” That was good advice. If Perry had taken it, we might not be in this jam.

Quick stats:

Change in population since 1989: 57%

Change in state road capacity since 1989: 8%

- More About:

- Politics & Policy