Politically, 1974 is shaping up as a momentous year: the President is in hot water, what James Madison called “the decisive engine of impeachment” is being cranked up for the first time in a century, and this fall’s elections promise the greatest congressional shake-up in a generation.

All of which helps account for the cataclysmic rhetoric and hyperbolic journalism currently emanating from Washington. In the midst of all that, though, as ever, arms are being twisted and egos crushed in the backrooms of government, quietly and without fanfare, politics as usual. Chief among the twisters and crushers, as befits the state which produced them, are two Texans. They have been jockeying for position for over a year now; prior to that, they each spent their lives trying to get where they are; in the course of those lives, they have crossed paths often; this year, they lock horns.

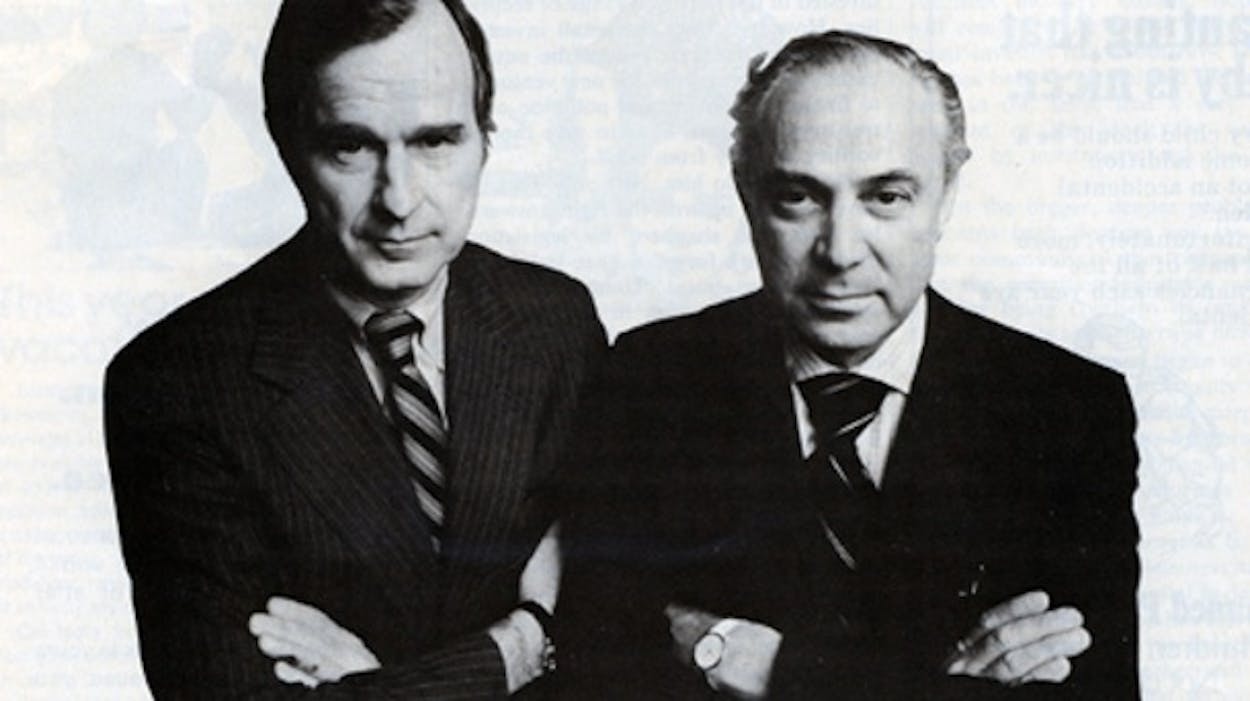

In less than a week’s time during December 1972, two Texans were named National Chairmen of the Democratic and Republican Parties. Robert Strauss, the Democrat, was a lifelong friend of John Connally—law school classmate, hunting sidekick, co-tenant of a lakeside cottage—yet lost the former governor to the GOP soon after taking office. Republican George Bush—who generously traded to the Democrats one of his own schoolmates, fraternity brother (Skull & Bones) and New York Mayor John Lindsay—graciously welcomed Connally, who had been largely responsible (in Bush’s estimation) for Bush’s defeat in the 1970 Senate election. The winner of that race, Connally protege Lloyd Bentsen, had been Bush’s occasional tennis foe and confederate in the same country club, as well as the first U.S. Senator to call for the election of Bob Strauss …

This all sounds rather incestuous, doesn’t it?

Politics, as we all know, is a game played by the powerful on a field of irony. And irony, just like politics, makes for curious bedmates… .

The Democrats had lately seen their standard-bearer, one George McGovem, suffer the most lopsided presidential defeat since James Madison ran unopposed. Despite their continued control of Congress and three-fifths of the nation’s statehouses, the party was fractured like anviled glass, filled with confusion and fraternal bitterness.

The GOP, on the other hand, suffered a more original but no less debilitating setback. A Republican president, to be sure, had rolled up the greatest landslide in history, but the party itself emerged with fewer major offices than it started out with. The Committee to Re-elect the President did an admirable job of accomplishing its purpose (perhaps less than admirable in its manner of doing so) but largely at the expense of the Republican National Committee. Kansas Senator Robert Dole, the outgoing chairman, complained that money, energy and manpower had all been siphoned off by CREEP while other GOP candidates were left to fend for themselves, generally without success.

Both parties, then, found themselves in trouble (“in disarray” is the way they say it in Washington) and in need of someone to get them out of it. Both parties turned to Texans.

The TV cables slink across the polished terrazzo floor of the Republican National Headquarters’ banquet room, between the folding chairs and the long line at the coffee urn. Most everyone here already knows what George Bush’s announcement is going to be, but they’ve all come out anyway, perhaps out of curiosity, perhaps just to mingle with their fellow journalists. They all shut politely up, though, when Bush comes striding across the room, directly up to the podium, to say what they all knew he would say:

“I have made a final decision. I will remain as chairman of the Republican National Committee. I will not be a candidate for governor of Texas in 1974. … ”

He has what political oddsmakers like to call “magnetism,” that being a kind of aura about him that falls just a notch below actual “charisma.” He gives the impression of being taller than he is, which is tall enough anyway, his features not so much handsome as strong, his gestures emphatic yet relaxed (not nervously exaggerated, like Nixon’s), his voice firm and authoritative, sentences crisply articulate. He seems like a man predestined to stand behind podiums and give speeches.

Yet there are less stately touches: His hair keeps falling in his face, he laughs easily, is casually witty, self-mocking. That’s something politicians carefully cultivate, that seeming naturalness (the easier for us stumbling voters to identify with them, but on Bush it still seems, well, natural.

As they say in Vegas: He’s a Class Act.

After his short statement come the questions, why this, why that, some of them stupid and garbled, some of them sharp and needling. Bush works well with the press, gives candid answers, witty answers, tolerant answers, never indignant and rarely evasive, his patience letting the questions drag out far longer than most politicians would allow.

One question keeps coming back, nagging again and again, always worded differently and always politely: Wasn’t your decision not to run prompted at least partly by a fear of Watergate backlash against Republican candidates?

No, says George Bush, Watergate had nothing to do with my decision; it’s a federal issue, not a state issue, it wouldn’t have affected a gubernatorial race. He admits there’s some difference of opinion on this but, well, he’s got these polls and everything, he can show you.

Indirectly, though, he admits that Watergate shaped his decision: “I mean, it just would’ve looked bad. It was a real no-win situation, they would’ve blamed it on Watergate whether I stayed or left. But after Elliot [Richardson] and Bill [Ruckelshaus] quit like that, it would’ve looked like I was abandoning ship or something. I just can’t leave while all this crap is going on.”

He doesn’t say that, however, to the Washington press corps. He says it, instead, back in his office, sitting around drinking coffee with a trio of Texas reporters who knew him and covered him back when he was a congressman from Houston. It’s a “background” session, he warns, nothing for publication, so for two hours the conversation rambles through old times and old races, Texas, Houston, tennis, the past, the present, the future.

But it isn’t really a backgrounder, not in any usual sense. National politicians don’t spend two hours backgrounding three homestate journalists on old times. What it really is, mostly, is therapy for George Bush, a chance for him to talk about Texas with a few Texans, an opportunity to relieve the frustrations of his decision. He really wanted to run for Governor, Bush did, and it hurts him that he’s not. And, dammit, he feels he could have won it. And so do the three reporters.

George Bush had always seemed a little like Scott Fitzgerald made him up, intent and earnest and ambitious, slicing through Life’s soggy dough with the easy grace of a man charmed:

George Bush, Connecticut-born of chandeliers and silver spoons. Episcopal gentry, banker-senator father and heiress mother, summers in Maine, winters in Florida, prep school at Andover;

George Bush the War Hero, youngest pilot in the U.S. Navy, shot down in the South Pacific and rescued by a submarine, only survivor of three aboard, winner of the Distinguished Flying Cross;

George Bush at Yale, Class of ‘48, twice captain of the baseball team, Skull & Bones, Phi Beta Kappa in economics;

George Bush who spurned it all, taking his new wife West, young man, to the blistered plains of Odessa, dusty streets and a frame house in the working class end of town, neighbors of a prostitute, $375 a month as an executive trainee;

George Bush who made it on his own, founded the Zapata Oil Co. (naming it after the Marlon Brando movie), built it into success and moved it to Houston, made his own million dollars;

George Bush the public servant, Republican congressman in a Democratic state, candidate for U.S. Senate, ambassador to the U.N., chairman, lastly, of the Grand Old Party.

Gatsby never had a thing on George Bush.

As with any proper hero, though, there are dents in the armor: overreaching ambition, excessive pride, tendencies, say his critics, toward condescension and opportunism. Trivial defects, these, even by the usual standards of heroic frailty which, God knows, are a healthy cut above the political. There is, moveover, a tragic flaw in Bush’s life, a vagrant irony that threatens his future, providing the narrative with dramatic tension and a touch of poignancy. It is his friendship with Richard Nixon, his close association with an administration floundering in scandal and despair.

A Yankee Republican of long standing, an old friend of former senator Prescott Bush, puts it thus: “I can’t think of a man I’ve ever known for whom I have greater respect than Pres’ Bush. I knew him during all his years in the Senate [1952-62] and I never once doubted his judgment or his integrity. Hell, he talked back to Joe McCarthy as a freshman senator and that was a damn tough thing to do. I’ve always been kind of sorry his son turned out to be such a jerk. George has been kissing Nixon’s ass ever since he came up here.”

A partner in the prestigious Wall Street firm of Brown Brothers, Harriman & Co. (that’s Averell Harriman, one should know), Prescott Bush shared his Brahmin Republicanism with the likes of the Lodges and Saltonstalls, a heritage reaching all the way back to the abolitionist origins of the GOP. More than any definable philosophy, it is rather a tradition, a kind of noblesse oblige that has men of “standing” offer themselves for “public service.”

Prescott Bush had helped start the “Draft Ike” movement while the Party warhorses were out beating the bushes for Bob Taft, later entered the Senate as a kind of low-keyed maverick, almost an independent missionary trying to civilize all the politicians.

Son George, meantime, was making his fortune in the Permian Basin oil boom, was active in every conceivable civic enterprise, was fundraising and speechmaking for the GOP. Like everything else in Midland-Odessa, politics is run on a frontier ethic, yer either fer-us er agin-us and thar ain’t no in-between; regardless of party labels, the ideological substance is skewed far to the right, as stark and narrow as the trees. The Republican Party of George Bush was as far removed from that of his father as Odessa from Greenwich.

When Bush moved to Houston in 1958, he brought along his oil company, his politics, and his inclination to public service. Five years later, he ran for his first political office—Harris County Republican Party chairman.

He attached his own label that time: “Goldwater Republican,” which, in Texas in those days, was understated redundancy. He became as active a county chairman as the Republican Party had ever seen, opening full-time offices, venturing into black wards to woo voters, taking public positions on local issues, bringing suits on election laws and redistricting. By the next year, 1964, Bush decided it was time to move up: he announced himself as a candidate for the U.S. Senate.

Democratic Senator Ralph Yarborough was, in many ways, even more of an outcast than a Republican in Democratic Texas. It wasn’t just that he was determinedly, aggressively liberal, though that would have been obstacle enough. But he was a well sworn enemy of the Texas Democratic Establishment, beginning all the way at the top with Lyndon Johnson and working down to encompass the past five state governors (most especially including then-incumbent Governor John Connally). Anyone who ran against him could count on heavy financial support regardless of party allegiance.

Bush launched a campaign that was well-organized, well-funded, well-advertised, bursting with energy and wholly devoid of party identification. He’s been oft-criticized for “being afraid to run as a Republican,” but, as he sees it, “it’s a matter of common sense. When you’re running in Democratic country you play down party labels. They do the same thing, it works both ways.”

In the 1964 Presidential Election, from Bush’s standpoint, the land slid the wrong way. In addition, Lyndon Johnson and Ralph Yarborough swallowed their personal enmity long enough to fashion a united Democratic front, and Yarborough was an easy winner. Bush, however, stacked up more votes than any Republican in Texas history, even while losing, and the meatpricers of politics all carefully noted his apparent popularity.

Two years later, he was ready again. Thanks in part to Bush’s own redistricting suit, the Texas Legislature had been forced to draw congressional districts that bore some marginal relation to where the voters lived, and a virgin congressional seat was opened in the middle-class western third of Harris County, home of George Bush and most of whatever Republicans there were.

Almost from the day the district was unveiled, Bush was running. The Democratic nominee, former district attorney Frank Briscoe, ran a campaign that was loudly against crime, sin, and race-mixing, and attacked Bush for being a carpetbagger from Connecticut. Out-lunged in competition for the Minute-man vote, Bush was paradoxically cast as the liberal in the contest (doubtless a curiosity for someone still owning up to “Goldwater Republicanism”), a misnomer that helped fashion his still-current reputation as a “moderate.”

Bush countered with a secret weapon: a young media wizard named Harry Treleaven whom Bush had discovered on (where else?) Madison Avenue. Treleaven, who later went on to bigger campaigns and greater glory (cf., Joe McGinniss, The Selling of a President, 1968), produced a series of flashy TV commercials that showed candidate Bush, coat-slung-over-shoulder, surrounded by family, tall and youthful, earnest and trustworthy. There was again no mention of political party (said Bush, “labels are for cans”) and scant reference to issues. He won hands down.

Bush landed in the Capital without even slowing up. His combination of Ivy League class and Texas style, family connections and oilman knowhow, made a near-awesome impact in Washington. He was universally hailed as “someone to keep an eye on,” and quickly welcomed to the bosom of D.C. society, an infinitely more difficult feat than merely getting elected to Congress.

As one of the leaders of the “New Breed” of GOP congressmen—all young, articulate, wholesome—he was named to the Ways and Means Committee, the most Olympian of all House committees, only the third freshman in this century so honored. He quickly set about earning his keep by building a reputation for expertise in oil matters. Remembers a Ways and Means staffer: “He was one of the sharpest people that’s ever been on this committee.”

The four years Bush spent in the House comprise the sole chapter in his political career when he spoke only his own mind, a free agent in the sport of government. Thus, they represent the truest distillation of his worldview, his beliefs; like everything else that comes filtered through Washington, it is confusing and ambivalent.

By simply feeding his voting record through the reductive threshers of the special-interest score-keepers (labor and business, left and right), he emerges as a Gold-Star conservative; not quite off in the brackish pools of obstruction where some of his colleagues swim but, still, at the salt-water line.

To judge a politician, though, on the sole evidence of his voting record is to take a sterile measure of him, to make a one-dimensional assessment. It’s rather like picking an All-Star team only on the basis of batting averages, discounting things like fielding, home runs, desire or (important category) stolen bases.

Judged on the same narrow terms, California Congressman Pete McCloskey—a Republican maverick who fought Nixon on the Vietnam war and called for his resignation—would seem just as liberal as Bush is conservative, yet he calls Bush “one of the finest men I’ve ever served with in the House. Of any party, whether liberal, conservative or what-have-you. George is someone you can count on to sit down and help find solutions to problems without considering the politics of the situation first. He’s got a compassion and open-mindedness that the rest of the Nixon Administration lacks.”

In his freshman year, Bush helped lead the perennial battle to reform the hide-bound House rules; later, he introduced an important ethics bill and fought for campaign finance legislation, became one of the first to disclose his personal finances; he was also an imaginative spokesman for population control and drew high marks from conservationists on other environmental matters. The most significant vote of his career, though, in most ways, came on the 1968 Civil Rights Act.

Although he supported several efforts to amend the open housing provisions in it, failing in each case, when the bill came up for final passage he voted for it. “All in all,” he said, “it’s a good law.” A good many of his arch-conservative avalanched with race-baiting hate mail, and he was the target of vicious invective and at least one assassination threat. He himself was stunned by the response: “It was worse than anything you could’ve expected. Some of it was sick, really sick.”

Bush’s response was, by the decidedly uncourageous norm of Washington politics, gallantly suicidal. Rather than diving beneath an ambiguous mountain of witless press releases (the accepted practice), Bush straightaway returned to his district to face the music. Weathering cat-calls and abuse, he faced down obscene fanatics to tell his constituents he did what he thought was right and, moreover, he wasn’t sorry for it. Played against the backdrop of hysteria and bigotry, Bush’s plea for understanding and common sense won him standing ovations; as performance it was high drama, and betrayed a depth of character that few politicians could muster.

Scott Fitzgerald would’ve loved it.

It’s eight o’clock on a Wednesday morning and Bob Strauss is crossing the Sheraton-Carlton Hotel lobby on his way to a Godfrey Sperling Breakfast, a ritual gathering of the best political writers in the nation’s capital. These breakfasts are sponsored by Godfrey Sperling, Washington bureau chief of The Christian Science Monitor, and are considered one of the most opportune places to “drop something,” to casually mention that such-and-such is about to happen, and get it rapidly disseminated throughout Washington and the Western World.

It is also one of the most fearsome places in America to eat breakfast, at least if one is the day’s “guest of honor.” To sit, at eight in the morning, surrounded by two dozen columnists and reporters like, say, Peter Lisagor, Bob Novak, David Broder, Roscoe Drummond, et al., all of them spearing you with sharp queries while you’re trying to eat badly discolored scrambled eggs, is not the cheeriest way to begin one’s day.

David Broder has already done a little pump-priming. His Washington Post column this morning had taken to task an outfit called the Democratic Advisory Council of Elected Officials, a group set up earlier this year by Bob Strauss with the intention of developing policy statements that most party members could live with, if not necessarily adhere to. Broder dismissed the Council as an ineffectual “vacuum” and laid much of the blame on Strauss-appointed chairman Arthur Krim.

One of the revelations Strauss intends to “drop” at the breakfast, prompted somewhat by Broder’s piece, is that he is inaugurating a number of “task forces” on various policy areas—environment, energy, foreign policy, the usual—designed to fill that vacuum. The other Strauss announcement is that a woman, Ms. Donna Smith of Kentucky, is being appointed to head a newly-created Washington liaison office for Democratic governors. The assembled press corps is not noticeably interested in either revelation.

Instead, while Strauss is grimly trying to ingest those eggs, they ask about changes in the party rules, why it is that a Democrat, Ohio Congressman Wayne Hays, is holding up passage of the Democrat-initiated campaign finance reforms, what did he think of off-year election returns, how long has he known Leon Jaworski, on and on and on, the eggs growing steadily colder and colder.

Strauss actually enjoys it, giving as good as he gets, spinning earthy parables in the best aw-shucks down-home manner, spitting four-letter expletives between mouthfuls of scrambled egg. The reporters, most of them veterans of two decades of the trapdoor callousness of Washington journalism, laugh with him, warm to him. For the most part he responds to their questions, but he does so indirectly, almost off-handedly, answering with a joke or a yarn or a wounded aphorism.

It’s an old game, of course, one that political reporters in Texas learned to play a long time ago. By erasing the line between questioner and respondent, transforming inquisition into conversation, guileless innocence emerges as honesty and opinion becomes a kind of aw-hell-we-all-know-thet fact. It’s shrewd, certainly: warmer, more human, but not altogether more truthful. One’s opponents, journalists particularly, are co-opted onto a neutral ground of quasi-friendship; compromise and agreement are facilitated, but debate and veracity get lost somewhere in the joshing and backslapping. Bob Strauss plays the game as an All-Pro.

Peter Lisagor is sitting next to him, trying to pin him down on Watergate; specifically, if Strauss thinks Nixon is as inept and bankrupt as he says, why not call for his impeachment? And, carrying that a step further, why doesn’t the Democratic Congress put its votes where its mouth is and vote impeachment instead of just yammering on about corruption and credibility?

Strauss is a little cornered on this one, says that it would look awfully partisan for the Democrats, or for him as Democratic chairman, to actually call for Nixon’s impeachment, “and if there’s anything this country can’t afford it’s for this mess to become a partisan fight, it might tear the country apart.”

Lisagor isn’t buying this, presses harder, wants to know why it’s any less partisan to badmouth the president for “illegal acts” than to do the next logical thing, i.e., to impeach him for those “illegal acts.”

Strauss is looking for cover: “It’s just like. … ”

That’s the tip-off that a yarn is coming.

” … those strip-tease dancers they used to have at carnivals and county fairs. They’d have a barker outside just like Nixon hollerin ‘C’mon in, she’ll take it all off.’ And when I was a boy we’d break our asses to get our sweaty little palms on a quarter so we could see the naked dancers. We’d go every time. … ”

Strauss is just getting started now, evoking all the sweaty-palmed horniness of a Lockhart, Texas, twelve-year-old, his eyes gleaming, grinning, two dozen hardnosed powerhouse newspapermen starting to smile.

” … the whole works’d be in this big carnival tent, and you’d get inside and its just darker’n hell except for they’ve got this light on the stage, and they’d start playin an old Victrola and the girls’d come on out. … ”

Strauss is gesturing and grinning, glancing around the table of reporters, looking them straight in the eye, smiling, drawing them in, back to Lockhart in the Twenties, watching dancing girls.

” … and they’d be bumpin and grindin and we’d be panting and sweatin. … ”

Even Lisagor is grinning, listening, and he’s lost it.

” … and then they’d ssslloooowwwlly take off a little bit of clothes, and then another little bit, and then that damn barker’d say ‘Well, that’s it for this show, need another quarter fer the next one,’ and so we’d have to go hurry up and find another quarter for the rest of it … ”

The reporters have long since quit taking notes, put up their pencils, chuckling to one another.

” … and we’d probably spent a couple dollars by this time, and she’s still takin off her clothes, and that barker is still breakin in just when it’s goin good, and I’ll be damned if I never did get to see that little old g-string. … ”

He’s a good yarn-spinner, Strauss is, able to hold them all, interest them, bring them along.

” … and it’s just like Nixon, he’s just like that old carnival barker, just strippin a little bit here, and a little bit there, and then sendin you away till you end up payin for some more. Then he’ll tell you just a little bit more about what’s goin on, but you never do get to see that g-string, he never does really get down and tell you the whole truth.”

The reporters have all guffawed and applauded Strauss’ earthy raconteurism, and he’s home free. They’re letting him off the hook, they know, but then he’d answered most of their questions, put on a good show, been infinitely better than most of the up-tight fence-straddlers that come to breakfast here.

On the way out, David Broder stops to shake hands, smiling, says “I don’t think The Christian Science Monitor has been this scandalized since Pete McClosky came here and said ‘bullshit.’ ”

Whatever benign star it is that tends George Bush’s destiny, lights his ambition, it was early on trapped in the flawed orbit of Richard Nixon. Bush’s meteoric ascent, in a decade’s time, from county GOP chairman to national chairman, including his prestigious ambassadorship to the United Nations, was due largely to the strong tug of Nixonian gravity. Likewise, his blunted hopes and dimmed future, like the Comet Kohoutek, result from the too-close approach to a fatal sun.

George Bush first met Richard Nixon in the Fifties, when the latter was vice president and the former was the son of a wealthy, popular U.S. senator. It was not until years later, though, when Bush was pursuing his own political career, that the two became friends.

Nixon campaigned for Bush in both 1964 and 1966, when Bush was first drawing attention as a hot property and Nixon was in mid-passage from crisis to crisis. When Nixon became president, Bush became a teacher’s pet; together with other young, moderate Republicans—Rumsfeld, Ruckelshaus, Riegle, Finch—he was soon a presidential favorite, described in the press as one of “Nixon’s Men.” Like Bush, they were all intelligent and ambitious, hardworking, possessed of an easy and casual charm. Bush is the only one still in the close company of the president.

When Bush gave up his safe congressional seat to run again for the Senate in 1970, he was invited out to San Clemente for a presidential pep-talk. Almost immediately, rumors began passing through Washington that, should he win, Bush might well replace Spiro Agnew as Nixon’s 1972 running mate. The rumor’s currency was abetted by the known fact that in 1968, though just a lowly freshman congressman, Bush was on a pared-down list of ten possibilities when Nixon was first nominated. In the two years since, the Bush-Nixon rapport had grown steadily closer.

Bush announced for the Senate fully expecting to win. Nixon was high in the polls, the Southern Strategy was lurching along at full throttle, and Ralph Yarborough was again the Democratic incumbent. Fully two years before the election, Bush staffers began building an arsenal to use against him. Remembers one of them: “We had a whole library on Yarborough, we knew more about him than his wife and his mother put together.”

But Fate’s monkeywrench, in the person of Lloyd Bentsen, Jr., jammed the gears of George Bush’s ambition. Fate’s mechanic was John Connally. Playing all the same tunes that Bush had been practicing for November, and with Connally’s chorus line to back him, conservative Democrat Bentsen unseated Yarborough in the May primary. Bush’s Yarborough Collection was rendered obsolete.

Defeated but still confident, Bush plunged into a singularly dull campaign against Bentsen. Or, better said, with Bentsen. Both candidates spent enormous sums to convince the electorate they were good family men with handsome children, church-goers and patriots who enjoyed long strolls in the woods. The only evident difference between them, judging from their own TV spots, seemed to be that Bush loosened his tie a little more and kept one hand in his pocket while strolling. A fatal error, apparently.

The turning point in the campaign, in Bush’s opinion, came less than a week before election day, when John Connally went on statewide television to denounce—not Bush, not Nixon, not the Republican Party or even Spiro Agnew—but the national economy, and endorsed his “good friend” Lloyd Bentsen. Bush lost his second race for the U.S. Senate by a greater margin than he lost his first. It was, he says, “a helluva blow, heartbreaking for my family and I.”

Looking back on it now, sitting in his office in Republican National Headquarters, he says “I don’t feel any resentment towards him [Connally]. He beat me clean and honest. He made filet out of me, but he never brought out the machete, never resorted to cheap demagoguery about being the ‘Ivy League carpetbagger who’s come down here to take over.’ [Note—the reference is to Frank Briscoe, who did.] He supported his friend and you can’t fault him for that. I’m glad to have him on our side.”

The words are there, and honestly delivered, but there’s no conviction in them. In normal conversation, George Bush looks you in the eye and talks with animation, emotionally, almost thinking out loud. When he speaks of John Connally, he stares in his lap and speaks quietly. He betrays hurt.

Within hours of the Senate election, Charles Bartlett, the syndicated Washington columnist and an old family friend, called to offer condolences. And hope. He told Bush of a powerful vacancy in the national hierarchy, one that he should try for and stood a good chance of getting—secretary of the treasury. Ambition rekindled, Bush flung his hat into the breach; he called his friend, Richard Nixon. Twenty-eight days after the election, the White House returned the call. Somehow, the lines into Houston got crossed. John Connally was named treasury secretary.

A month later, Bush got his consolation prize: Nixon appointed him U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Foreign Service veterans and State Department pros were disconsolate, muttering into their brandy that a “politician”—one wholly untutored, moreover, in the high arts of diplomacy or the watchworks delicacies of U.N. etiquette—had no business representing the U.S. on so fragile a stage. But Bush surprised them.

With his double-barreled come-on of Brahmin polish and Texian hustle, Bush stormed the U.N. with the same enthusiasm he’d earlier used to assault Congress. He became a new kind of U.N. ambassador: backslapping with foreign ministers, trading jokes in corridors and deals in anterooms, taking them all to the Mets games. Beneath all the multinational folderol, he’d discerned a simple truth: The U.N. votes on things, and votes mean politics and politics is what George Bush is best at in all the world.

Within six months he was being called the most effective U.N. spokesman this country has ever had. If he lost his most important battle—the vote to supplant Nationalist China with mainland China—he at least made it a horse race, and he won another that everyone said he’d lose—the vote to reduce America’s share of the U.N. bill.

But dark clouds, as they say, were gathering over the White House. Republican chairman Bob Dole had gotten on the wrong side of Chief Inquisitor Bob Haldeman—insufficient fealty was the charge—and Haldeman wanted him out. That was easily arranged. For a replacement, the White House sought someone with both unquestioned integrity and unquestioned loyalty to Richard Nixon. A rare animal indeed. Nixon called on Bush, who didn’t want to leave the U.N. (“It was the most fascinating experience you could hope for, the chance of a lifetime.”), but he did. Three months later, James McCord wrote a letter to John Sirica and The Year of Watergate was begun.

Bush was once asked if he didn’t think he’d had, well, a rather bad run of luck in his political career, what with his knack for timing and all …

“Oh, I don’t know as you could call it bad luck,” he answered. “After all, sometimes it turned out all right. I’d have never got to the U.N. if I hadn’t made the Senate race and lost, I guess. You know, I was talking to Nixon once and he said to me that we’re all controlled by events. And I just looked at him and said, yeah, uh-huh, whatever you say, and later on I wondered just what’n hell he meant by that. But I thought it over and after a while started to understand what he was saying. What I mean is, I guess I’m kind of a … fatalist. … ”

Under Texas’ “weak governor” system of government—wherein a baffling array of administrative posts are filled by election rather than appointment—scant few sinecures of influence remain for gubernatorial patronage. One that does is the governor’s slot on the three-man State Banking Board, which doles out state bank charters and hence occupies strategic high ground on the geopolitical battlefield. Another such post is Democratic national committeeman, the key liaison wtih the national party for a governor with national ambitions.

When John Connally was governor of Texas, Bob Strauss got both jobs. In 1963, he filled Connally’s first vacancy on the Banking Board, went on to serve throughout the Connally incumbency. He became national committeeman in 1968, at the same State Convention that chose Connally to be Texas’ favorite son candidate for the Democratic Presidential nomination. Strauss’ predecessor was Frank Erwin, Connally’s chairman of the U.T. Board of Regents; the national committee-woman at the time was Mrs. Lloyd Bentsen, Jr.

Connally’s kinship with Strauss extended back beyond Connally’s rise to personal power. Both had earned their political spurs in the 1950s, when they were key lieutenants in the Lyndon Johnson-Sam Rayburn wing of the State Democratic Party. The goals of that faction were three-fold: to take control of the state party, to keep it within the mainstream of the national party (or at least on the bankside), and to elevate Lyndon Johnson to the presidency.

Strauss’ role within that general scheme was basically that of a fundraiser. Following law school and the War, he had joined a successful, middle-sized Dallas law firm, branched out into various business ventures of his own (communications, clothing, insurance), and sunk his roots deep into the Dallas financial community. Playing his contrapuntal connections with business interests against those with political movers, he beat out a rhythm that channeled considerable cash into the coffers of favored candidates.

One longtime Dallas political hand recalls: “Strauss was one of those people you went to early on, when you were planning a campaign. He always spoke for more than just himself, and he could get you a lot of money besides just his own. You wanted him on your side.”

Following his selection as national committeeman, Strauss became Texas finance chairman for the 1968 Humphrey-Muskie campaign. Despite the fact that friend/benefactor John Connally took a decidedly low profile role in that effort—some Democrats charged that Connally was supporting Nixon up until the last week of the campaign—Strauss himself was a whirlwind; a former Humphrey staffer says “he worked his ass off for us.” The Texas campaign was alone among the big states in paying all its bills, even sending some money along to the national party.

Shortly after the Humphrey defeat, Strauss was rewarded for his labors (and his connections) with election to the executive committee of the national party. Sort of the ruling politburo. It was from this vantage point, later in 1969, that Strauss pulled off what came to be known as his greatest coup.

The Democratic Party was sponsoring a $1000-a-plate fundraising gala in Miami Beach; months had been invested in preparation and a raft of Democratic superstars recruited to man the dais. Yet debacle loomed. A week before the dinner the hall was still half-empty and near-broke. With a typically Texan flare for drama and audacity, almost with bugles blowing and drums rolling, Bob Strauss came to the rescue. Into Miami flew a chartered jet filled with up to $100,000 worth of Lone Star high-rollers, plus the governor, the lieutenant governor and a host of Texas functionaries. Strauss was hailed as The Hero of Miami Beach and the nearly-ruined dinner proclaimed a grand success.

Strauss’ detractors like to point out that, in reality, most of the plane’s occupants dined for free and that the reported receipts from the Texas contingent came to under $30,000. Said detractors overlook the fact that in politics, as in everything else, it’s appearance that counts. Strauss’ Texas airlift spared the national party the embarrassing hemorrhage of a fizzled gala, and they were grateful.

By the spring of the following year, Strauss’ special talents were increasingly needed by the national party. Still burdened with several million dollars in unpaid bills and every day sinking further into debt, with nothing to look forward to but future expenses from upcoming campaigns, the Democratic Party was awash in bad paper. “If it was a corporation,” said one party official, “it would declare bankruptcy.” In addition, National Chairman Fred Harris, an Oklahoma Senator, was becoming more concerned with his own reelection and less interested in the national committee, and the party grew moribund. The search was on for new, revitalizing, leadership. It found Larry O’Brien, the old Kennedy hand, and Bob Strauss, and elected them chairman and treasurer.

From the first, O’Brien and Strauss saw themselves as a team working to streamline the Democratic apparatus. Strauss received unprecedented budgetary authority, and set about reducing the debt. By inducing party fatcats to send in regular subsidy checks while simultaneously cutting payrolls and expenses, O’Brien and Strauss had the party operating in the black within eight months.

In spite of his fundraising success, Strauss was beginning to draw fire from the Democratic left. Ralph Yarborough, shortly after losing his primary match with Lloyd Bentsen, blasted Strauss for his Connally connections and called for his resignation. According to Yarborough, Strauss has been responsible for the defeat of a party registration resolution at the State Convention, thus allowing Republican cross-over voters to swamp Democratic primaries.

Strauss denied the accusations and counter-attacked. He laid into liberal eminence John Kenneth Galbraith for supporting George Bush over Lloyd Bentsen in the Texas general election. Strauss’ attack on Galbraith led to a long-running (and still continuing) feud with the Americans for Democratic Action, a left lobby which Galbraith had once served as chairman.

Strauss next got into a flap with liberals by opposing the adoption of reform rules proposed by the O’Hara Commission (soon to become the McGovern Commission). Still later, he got into another imbroglio back home by supporting efforts to water down reform attempts within the Texas party. As the 1972 elections approached, he got himself into yet another hassle by endorsing Johnson/Connally heir apparent Ben Barnes in the Democratic gubernatorial primary. Both Preston Smith, the incumbent governor, and Dolph Briscoe, the eventual winner, fired off quick denunciations of Strauss’ gratuitous intervention.

It was this record that Bob Strauss, in December of 1972, brought to his campaign for national chairman. Almost immediately after George McGovern’s disastrous confrontation with the American electorate, disgruntled party pros and conservative office-holders called for the removal of Chairperson Jean Westwood, a McGovern appointee. In matched-set press releases, on the same day, Connally and Bentsen suggested Strauss.

He quickly gained the support of two groups which felt themselves cut off from influence within the national party: the AFL-CIO, led by George Meaney, and the Democratic Governors Conference. Aside from McGovern and an amorphous collection of disunited liberals led by the ADA, Strauss’ only real opposition came from Senator Edward Kennedy.

Almost nobody denied that Strauss had put in yeoman’s service as party treasurer. What the liberals held against him was essentially his association with Connally. Since Connally, however, had not yet formally bolted the party, the Floresville Connection was not the obstacle it might have been six months later. Strauss’ opponents were without any real issue, and without a real candidate (many of them deserting Westwood and looking for somebody else).

By the time of the National Committee meeting in Washington, Strauss had mounted the only full-blown, wide-open campaign for the post. Even at that, against divided opposition he polled only 41/2 votes more than the necessary 102 vote majority. Joked Strauss, “I wasn’t exactly drafted into this job.”

With that shaky mandate to support him, Strauss was installed as party chairman. He gave all the customary speeches about unifying the party and set about trying to make it solvent. To help him, he found a young man named John Brown, the Kentucky Fried Chicken magnate.

Strauss and Brown unveiled a mechanism never before attempted in the political arena: the telethon. With a kind of Variety Show/amateur hour/ Billy Sunday/razzle-dazzle format, the Democratic Telethons became the biggest success story in fundraising history. Together with Strauss’ negotiations with creditors, the Democratic debt was cut from $10 million to $3 million in the space of a year. Strauss now calls it “manageable.”

He also removed the party from the ostentatious and ill-starred Watergate complex, further cut salaries and allowances (including his own), and systematized office procedures. Delivering on his campaign pledges, he brought in office-holders who’d felt themselves excluded from the earlier party framework, especially Democratic governors. He began a series of workshops and strategy meetings designed to target winnable races and recruit candidates, all of it fitting into his plan to “make the national party a service organization for local Democrats, somewhere they can come when they need help and advice.”

From the 1972 National Convention he’d inherited four specific mandates—commissions on the charter, on delegate selection rules, on the procedures for vice-presidential nominations, and a mid-term “policy conference.” While there is little he can do regarding most of those mandates other than seeing that they happen, the delegate selection commission has become his biggest headache.

Like most conservative Democrats, Strauss would like to roll back many of the procedural reforms inaugurated by the McGovern commission. Liberals, on the other hand, led by the commission’s fiery chairwoman, Baltimore City Councilwoman Barbara Mikulski, are determined to preserve them. Like Jean Westwood before him, Strauss has used his appointive powers to stack the committee to his best advantage, but the net result of the Strauss/Westwood logrolling has been, surprise, a well-balanced commission. While still far apart on their wishes, both Strauss and Mikulski have been amiably trying to reach a compromise that won’t jeopardize the Democrats’ new-found spirit of fraternity.

Strauss, of course, still draws fire from the liberals and still manages enough gaffs to keep himself in at least luke-warm hot water. In a recent TV interview in Dallas, for example, he found himself discussing prospective Democratic presidential aspirants in a slightly more partisan manner than he should have been. An Associated Press wire story greatly exaggerated his unenthusiastic assessment of Senator Kennedy, and there was hell to pay when he got back to Washington. He produced a copy of the TV transcript, which sufficed to smooth over the rough edges, but the incident illustrates Strauss’ still-uneasy relationship with his party’s liberal bloc.

National party chairmen are a strange species of politician, not unlike the Visigoth warlords who collected around ritual campfires a misshapen army of the dumbstruck and greedy, allied only in pursuit of plunder. The Constitution of the United States makes no mention of political parties; they are the product of historical happenstance, and all of their symbols, trappings and infrastructure were the creation of men, not laws.

The chairman presides over a bizarre assortment of personalities: wealthy contributors, influential functionaries, transient governors, congressmen, legislators, occasional presidents, 50 state party chairmen each with variant collections of subalterns; they all function (after a fashion) under charter and bylaws of their own making, through an amorphous chain of command that alters from place to place, day to day. Their chairman, who has no real access to institutional power, is supposed to organize this prestigious rabble to achieve the one thing they are all agreed on: ever greater electoral success under their own banner.

It is to this single-minded but unguided task that George Bush and Bob Strauss have lent themselves. They share the qualities most needed for such work-energy, pragmatism, intelligence, and a kind of transcendent friendliness. Neither one is considered an ideologue by the vast majority of their party fellows, and both have earned broad respect for their labors. If Strauss has offended a few more Democrats in the course of his perambulations than Bush has Republicans, then it’s probably because the Democrats are a much more diverse (and outspoken) breed of politician.

Both of them have logged well over 100,000 miles on the rubber-chicken banquet circuit, both have held innumerable press conferences and delivered countless speeches. In the process, to a large degree, they have both subordinated their own views and ambitions to those of their party.

Says Bob Strauss: “Well, of course, I’ve got my own favorites in things, but it isn’t my job to try to make them happen. Jesus, I’m busy enough just trying to get the party together and win some elections without stepping over myself in the process.”

Says George Bush: “I’ve crossed a kind of Rubicon, I think. For ten years it was inconceivable to me that the nation could survive without me in elective office someplace. Now, at the age of 45, I’ve discovered that the Republic might just get along quite well without my services.”