“Do you want to talk about your relationship with your father?” I ask.

George W. Bush’s lips press together and his eyes narrow above his bifocals. For a man of 47 years, he still looks surprisingly youthful. There are few wrinkles on his face, and when he forms his trademark smirk, a sort of half-grin that pushes the corners of his mouth straight up, he resembles a cocky college kid. It doesn’t take much, however, for his smirk to turn into a sneer.

“Are you going to write that kind of article?” he asks me, his voice getting edgy. “One of those pseudo-psychological me-and-my-dad stories?”

Bush sighs and looks out the window of his office, in a North Dallas high rise. Out of that same window in 1992, he watched a kid selling hundreds of “Ross Perot for President” T-shirts to drivers exiting the North Dallas Tollway. He got on the phone to Washington and told his father, “We could be in trouble.” George Walker Bush has always identified closely with his father, George Herbert Walker Bush. “He’s probably more loyal to his father than any of the Bush children,” says a family friend. It was George W. who went to Washington to tell the president that his chief of staff, John Sununu, had to be fired. It was George W. who took it upon himself during one of the presidential campaigns to screen all of the journalists who wanted to do interviews with the elder Bush. He would lean back in his chair, stare at the writers, and say, “Give me one good reason I should let you talk to George Bush.”

The writers called him arrogant. “Just doing my job,” George W. would reply, “protecting the old man.”

But on this February afternoon, he doesn’t want to talk at all about the old man. He has practically banished the old man from his race for governor. In his stump speeches, George W. never mentions his father, the leading Republican in Texas. The elder Bush is not doing any interviews or making campaign appearances. “The only reason I’m talking to you,” says George W., pointing his unlit cigar at me like weapon, “is so people can know what I stand for, not so we can discuss family history. The minute the other George Bush wades into the process, my message gets totally obscured.”

Yet it is obvious that the elder Bush is not only part of the process but also the essence of that process. What else could explain the statewide poll conducted last October, before George W. Bush’s announcement for office, that showed he would be only eight percentage points behind Governor Ann Richards if the election were held that day? Bush is keenly aware that a lot of people, even those who swear allegiance to him, don’t know a thing about him as a politician except that he is the former president’s boy. George the Younger, he’s called. The First Son. The Shrub. Regardless of how much George W. Bush wants to talk about issues, the decisive factors in many voters’ minds are likely to be how they perceive him to be like his father and how they perceive him to be different—whether they believe he has his father’s strengths or his weaknesses.

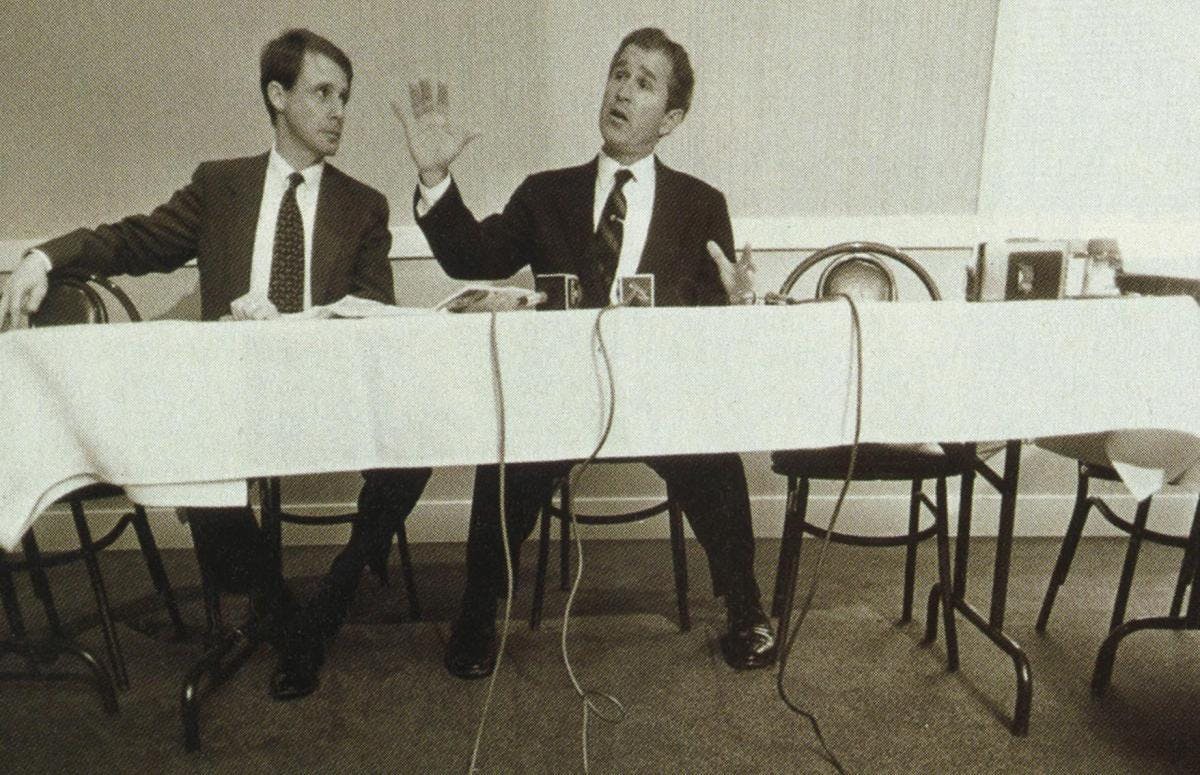

Ann Richards’ most piercing attack against Bush is that he has done nothing to prove himself as a leader. Yes, he ran an oil company and then helped put together the group of investors that bought the Texas Rangers baseball team, of which he is the managing general partner. But until his gubernatorial announcement, he had only taken a cursory interest in politics: an impulsive 1978 run for Congress and work in his father’s presidential campaigns. Bush’s critics claim he is little more than an untested candidate who hides his ignorance of government behind a wall of self-confidence—and behind his last name. “If his name was George Smith,” snorts a Richards aide, “no one would take him seriously.”

Bush’s friends and supporters, however, portray him as an articulate, quick-witted leader, a far better debater than his father, and surprisingly, a savvier politician. Nor is he timid about matching his personality against that of the legendary wisecracking Richards. “Don’t underestimate this guy,” says Fred McClure, a former senior legislative aide to President Bush in Washington and now a Dallas financier and neighbor of the younger Bush. “He’s no doubt the biggest political animal in the family—and clearly more competitive than his father.’

Demonstrating that he has indeed learned from the mistakes of his father, Bush is trying to paint Richards exactly as Bill Clinton painted the elder Bush during the 1992 presidential campaign: as a likable but ineffectual incumbent, a defender of the status quo. Bush has already positioned himself as the candidate of change in this campaign. He has introduced proposals to overhaul the state’s public education, welfare, and juvenile justice programs. He uses phrases—”the landscape for change,” “a startling new vision”—that surpass normal Republican lingo. “Believe me,” says Bush, “I’m not afraid to shake things up. Otherwise we’re stuck with more of the same problems no one has ever had the guts to fix.”

In his office, Bush sighs again. He knows he is embarking on a grueling personal journey to step out of the shadow of his beloved old man. “All that I ask,” he says, giving me another glare, “is that for once you guys stop seeing me as the son of George Bush. This campaign is about me, no one else.”

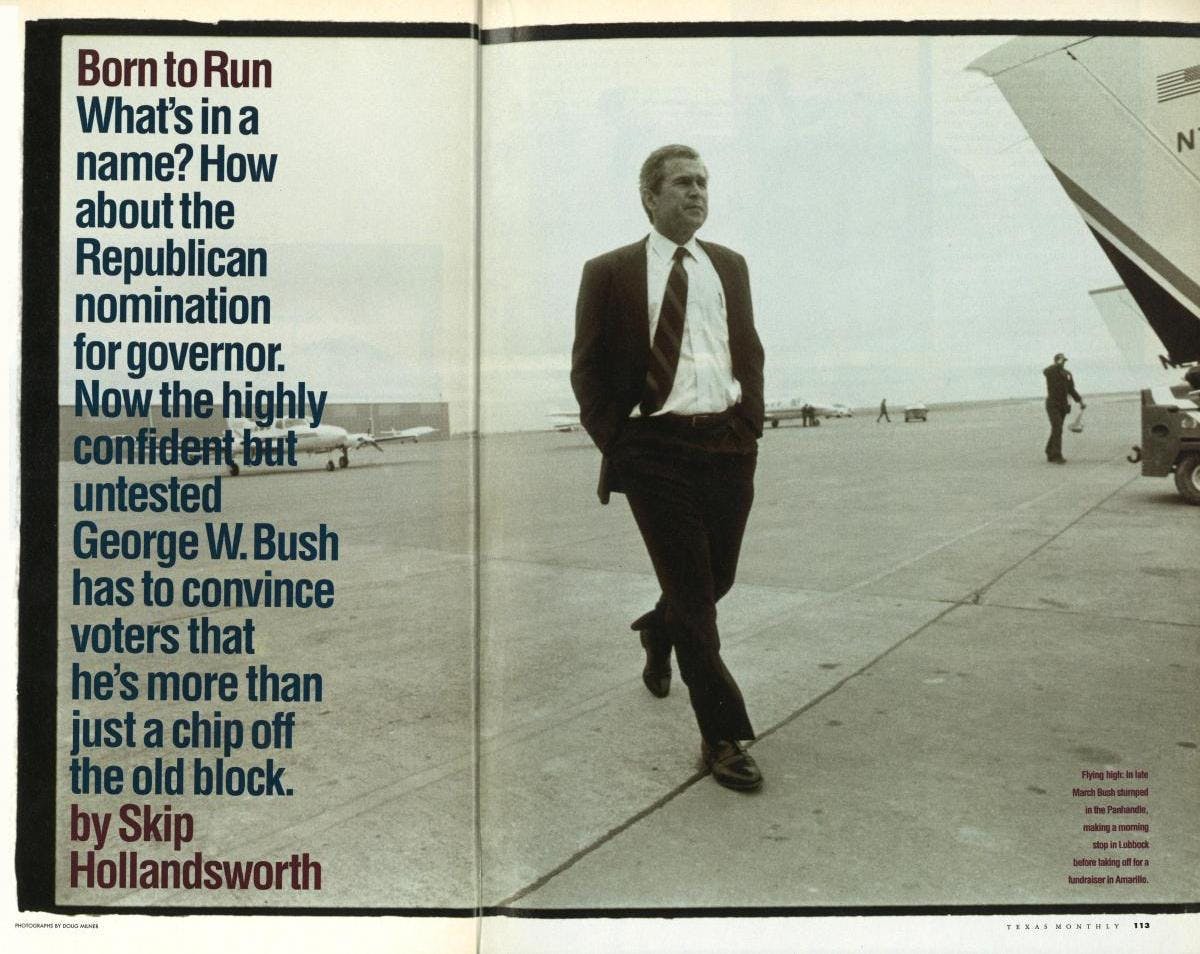

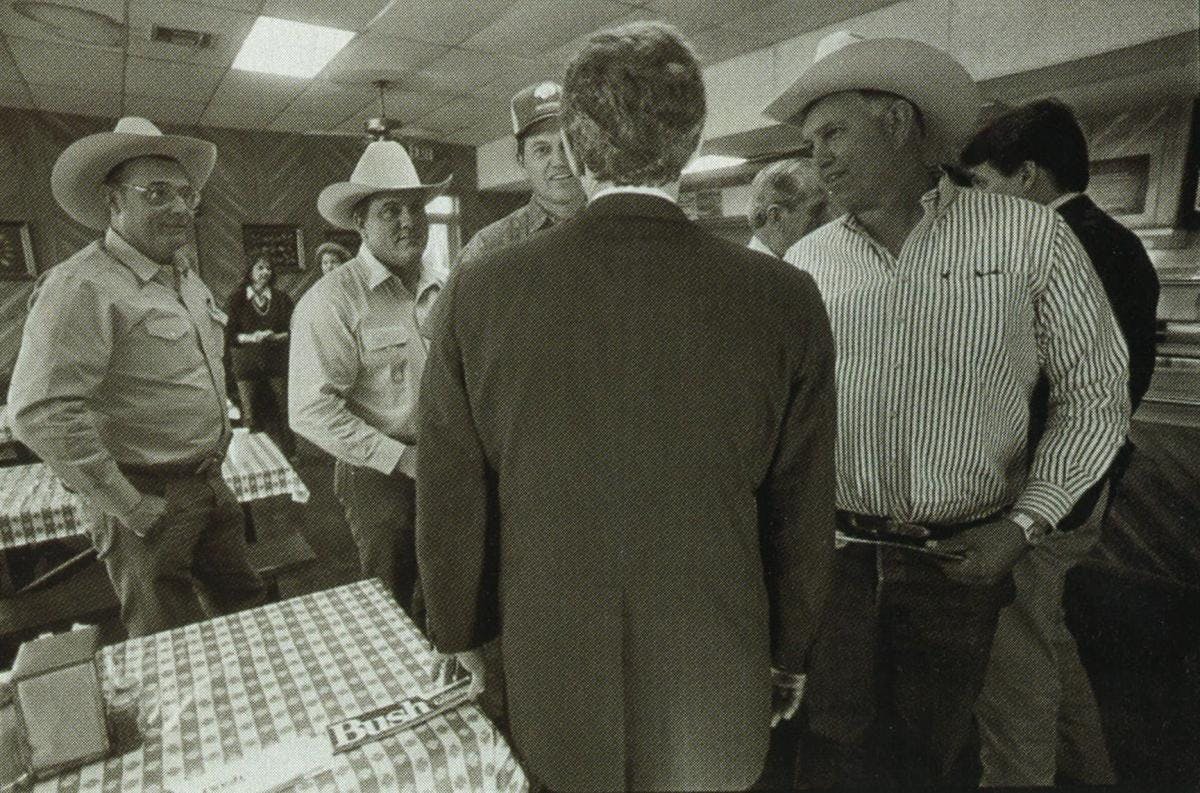

“If the election was held on Southwest Airlines,” Bush tells me, ‘‘I’d win in a heartbeat.” We are on a morning flight from Dallas to Midland for a campaign appearance, and he has already signed half a dozen autographs on cocktail napkins for other passengers. On a Southwest flight a few days earlier, sixteen people sitting in the eight rows behind him handed him a sheet of paper that they had signed, promising to vote for him. Before boarding a flight on another day, he ran into Roger Staubach, a former Dallas Cowboys quarterback and avid Republican who is rumored to be a future political candidate himself. The autograph crowd—on that day, middle-aged men in dark suits—had gathered around. “Hey, Roger,” Bush joked. “I want you and Nolan Ryan [the retired Rangers pitcher, also a Republican] to campaign together for me in the fall. We’ll call it the Old Farts Tour.”

Like his father. Bush gets an adrenaline rush when he’s out campaigning, shaking hands with strangers, saying “Nice-ta-mee-cha,” and cheerfully telling them, if they are unsure of how to reply, that they should come out to watch the Rangers play in their new stadium. He also has his father’s gift for remembering names. Often he travels with only one young aide, Israel Hernandez, who gives him a schedule of the day’s events and hands him breath mints—about a dozen a day. “Hand me a mint there, Israel,” Bush says when he shows up at a campaign stop, then he’s out of the car with jackrabbit speed, jaw-boning with everybody. There is no one whispering into his ear the names of his bigger supporters. Bush knows them.

Unlike his father—who startled voters with his inane asides (who can forget the time he walked into a New Hampshire company cafeteria in 1992 and amused diners with his off-the-cuff “Don’t cry for me, Argentina” remarks?)—George W. has the ability to win over strangers. On the Midland flight, he sees a boy wearing a Rangers hat and says, tongue in cheek, “Listen, kid, work hard at baseball and you too can get a $45 million contract like Juan Gonzalez.” Pause. “But if you can’t hit the curve, please try to make a nice income when you grow up so you can buy lots of Rangers tickets.” The passengers chortle and hand him more napkins to sign.

While the elder Bush has always been known as an unfailingly polite man, George W. takes pride in his own irreverence. He loves to needle his friends. He can cuss like a sailor. And he tells stories with great good humor, even the embarrassing ones about himself. If his dad, as the Washington Post once wrote, really is a slight bore, like “every woman’s first husband,” then George W. is the wild boyfriend every woman dated in her youth. His closest pals, who all say he can act brash and cocky, have nicknamed him the Bombastic Bushkin.

“I must say young George is very much of a different generation,” says Barbara Bush, who lets me visit for an hour at the Bushes’ new Houston home, where she is working on her memoirs (“My editor,” she sighs, “says I’m using the words ‘wonderful’ and ‘precious’ too often to describe all my friends”). “With my other governor son, Jeb [who is seeking the Republican gubernatorial nomination in Florida], you still see the old gentle Bush demeanor. But this George”—and she begins chuckling—”he’s something else entirely.” When the queen of England came to the United States and had dinner with the Bush family, Barbara seated George W. at the other end of the table so he wouldn’t be heard saying anything offensive. “He’s the Bush black sheep,” she proudly told the queen.

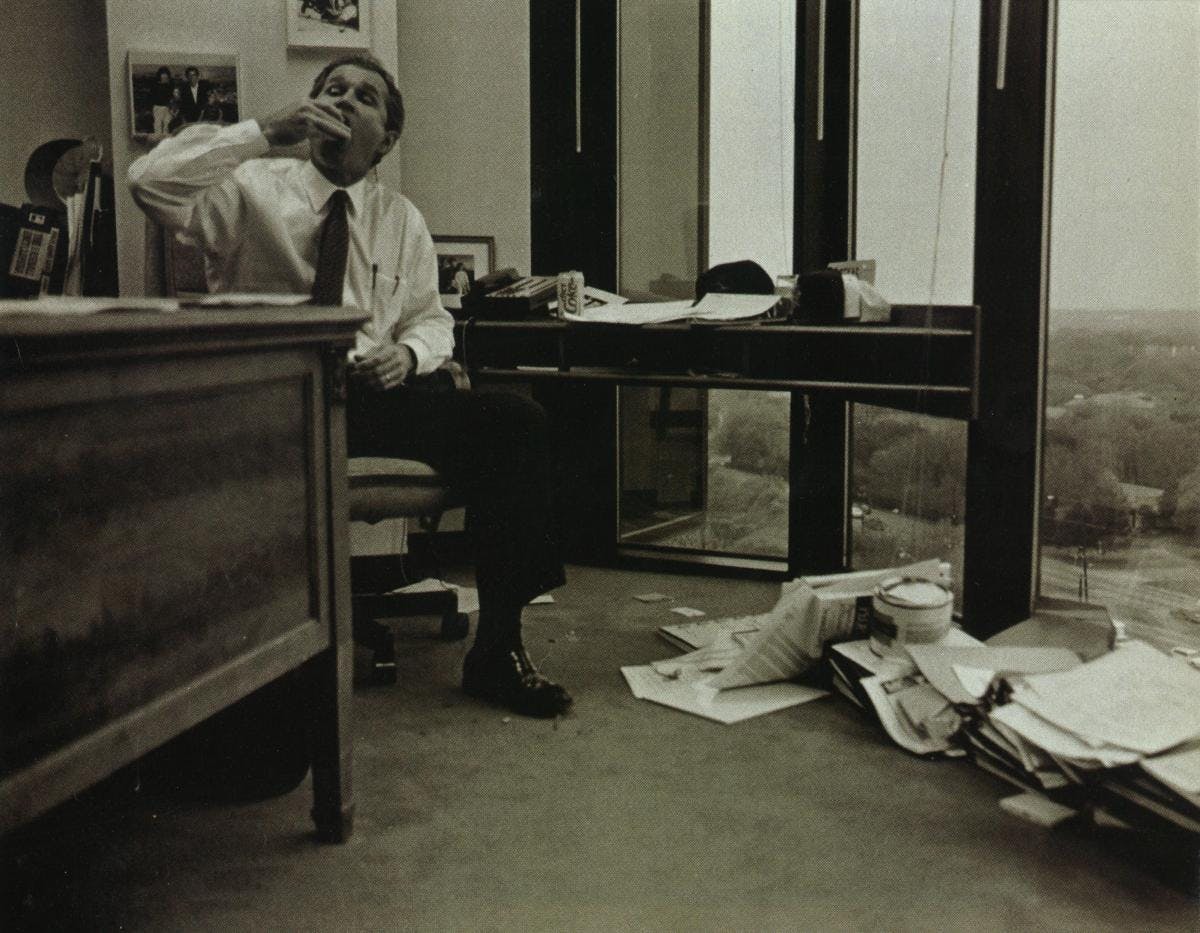

Bush does have a casual style that’s rarely seen in his patrician parents. When he strides into his office in Dallas, he throws his inexpensive Haggar sport jacket on the floor—he has no coatrack—and eats from a bag of popcorn as he answers phone calls and shouts at his secretary through the always open door. His office is decorated like a dorm room. Baseball gloves and baseball bats and replicas of Bowie knives are scattered about. A Texas flag lies on top of a counter, half buried under some books. A personalized Texas license plate—reading BUSH—is on another table. The Baseball Encyclopedia is near his chair. Although a few photos have made it to the wall—an autographed shot of Nolan Ryan; Mom in a Rangers Jacket; him and his father fishing; his wife, Laura, and his twelve-year-old twin daughters—a large stack remains on the floor, in a corner.

Something Bush has inherited from his father is a kind of manic energy. He ran a marathon in Houston after the 1992 presidential race (finishing in a respectable 3 hours and 44 minutes). He prefers to spend his lunch hour running and sometimes lifting weights at Dallas’ tony Cooper Aerobics Center. At the end of the day, in his comfortable one-story North Dallas home, Bush sits at his desk in an office just to the right of the front door, simultaneously talking on the phone, flipping through television channels with his remote control, and helping his daughters, who attend Hockaday, the most exclusive private girls’ school in Dallas, with their homework. Sometimes he leaps up and heads out to the front yard with his Springer Spaniel, Spot (a daughter of the former first dog, Millie), and throws a tennis ball for her to chase.

“I wouldn’t say that patience is one of George’s greatest qualities,” says Laura, a soft-spoken former public school librarian, the yin to Bush’s yang. She is neat and thoughtful, while he is exactly the kind of guy librarians are always telling to stop talking. On the day of my visit, she had been preparing a report for her women’s book club on Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate.

Laura initially felt reluctant about Bush’s entering the governor’s race. “She wanted to be sure I was running for all the right reasons,” Bush tells me, “and that I wasn’t running because I felt I had something to prove.” It is a striking admission, for it suggests that even those closest to Bush have wondered about his need to become governor. Ambition, of course, is a tricky matter: All politicians are motivated to run for office through some mixture of private needs and public desires. But because Bush is the son of a famous man, and especially because he is trying to prove he can succeed at his father’s profession, his drive to become governor is perhaps a little more perplexing. Is this campaign his grand attempt to win his father’s approval? Is George W., the loyal son, running out of spite against Ann Richards, who has never hesitated to take potshots at the Bush family, as in her famous 1988 Democratic Convention speech, when she said that the elder Bush was born with a silver foot in his mouth? Or is it because he has a plan, as he says in every campaign speech he gives, to turn Texas into “a beacon state, a place where other people say, ‘That’s what I want my state to be’”?

Bush makes a point to tell me, over and over, that he has never had long-range political ambitions. “I’ve never been a long-term planner about anything,” he says. “I have lived my life with more of a short-term focus—on the theory that other interesting things would come up for me to do.” If there is a theme that runs through Bush’s adult life, it’s that of a man who quickly, sometimes impulsively, seizes the opportunities that are put before him. He admits he never considered becoming an oilman until the day he stopped in Midland for a brief visit in 1975 and decided to stay there. He says he never planned to buy a major league baseball team until a friend gave him a tip in late 1988 that the Rangers were for sale. And he swears he didn’t make up his mind to run for governor until June 1993, “when everything began to feel right and when everything that Ann Richards was doing, or not doing, began to feel so wrong.”

All of his friends say in interviews that Bush is sincere in his concerns about the deteriorating state of education and the widespread fear of crime in Texas. But, they add, to understand the candidacy of Bush, it is important to understand what it means to be a Bush in Texas, a member of Texas’ most famous political family. Congenial and close-knit, the Bushes are far from a tortured clan like the Kennedys, with their scandals and their obsessive drive toward power. The Bushes obviously feel imbued, however, with an invincible sense of self-confidence, a kind of family faith, a conviction that they are the right people to lead.

“I’ve thought for a very long time about this,” says Midland orthopedic surgeon Charlie Younger, one of George W. Bush’s closest friends for nearly twenty years. “I know that he likes competition and that he relishes the battle of going against Ann Richards. I think—and this is pure speculation—that he didn’t like what Richards did to his dad and he wanted to make some amends.”

Younger thinks for a few moments, considering whether to say more. “I also know this desire to run is in his blood,” he finally says. “It’s part of being a Bush. He has come around to seeing himself as the oldest and heir apparent to the clan.”

George W. Bush has often joked that the key difference between him and his father is that “my dad went to Greenwich Country Day School in Connecticut and I went to San Jacinto Junior High in Midland.” The elder Bush was raised in a home with three maids and a chauffeur. He went to tea dances. At home, he had to wear a coat and tie to the dinner table. George W. grew up in a nice but unpretentious neighborhood with a bunch of brash, rough-and-tumble oilmen’s sons—and he fit right in. Early photographs of George W. show a boy with a rakish gleam in his eye, an amused look on his face—”A wonderful, incorrigible child,” says Barbara, “who spent many afternoons sitting in his room, waiting for his father to come home to speak to him about his latest transgression.”

Perhaps because the elder Bush felt it so difficult to shake loose from the influence of his own stern father, U.S. senator Prescott Bush, he never played the role of the fierce disciplinarian with his own children. “I can’t exaggerate to you what wonderful parents George and Barbara Bush were,” George W. says. “They were liberating people. There was never that oppressiveness you see with other parents, never the idea that their way was the only way. My dad went out of his way to make sure that I felt accepted by him.”

If such fatherly support helped instill in the younger Bush a sturdy self-assurance, his mother gave him her tart tongue and free spirit. To this day, they tease each other mercilessly. Once, George W. had been forewarned by another family member that his mother was grieving over the death of her beloved dog C. Fred. “So he came through the front door,” remembers Barbara, “and shouted, ‘Hey, Mom,where are you, doggone it?’”

When Bush talks about “the family as the backbone of Texas” and “Texas as a wonderful way of life” in his gubernatorial campaign speeches, what he’s referring to is his own Midland childhood. This is not the Midland that Clayton Williams, the last Republican gubernatorial candidate, described during his 1990 campaign. Williams’ Midland was a world of flamboyant wildcatters and cowboys. Bush’s Midland, however, was a world full of people like his parents, Ivy Leaguers who had come to West Texas to make their fortunes. The families got together for golf at the country club. They had backyard barbecues in their neighborhood—a neighborhood no different, really, than any upscale neighborhood in Houston or Dallas. They went to First Presbyterian and joined the board of the United Way and sent their kids off to private schools back East. Although the younger Bush saw his parents mingle with poor people, theirs was a world devoid of hardship.

Like his father, George W. attended the exclusive prep school Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts. He distinguished himself early. His English teacher, a Mr. Chips type, asked the class to write an essay on emotion. Wanting to impress his teacher, the young Bush looked up synonyms for “tear” (as in “droplets from eyes”). Unfortunately, he looked up “tear” (as in “to cut”). Bush wrote, “Lacerates ran down my cheeks.” The professor gave him a zero.

In the mid-sixties Bush went off to Yale to major in history. “I wasn’t exactly an Ivy League scholar,” he says with a good-natured grin. “What I was good at was getting to know people.” Considering Bush’s collegial nature today—his styled casualness, his tendency to greet male friends with the phrase “Hey, buddy”—it should come as no surprise to learn that at Yale he was president of his fraternity, the Delta Kappa Epsilons. Although he did not graduate Phi Beta Kappa as his father had, he did follow his father into the university’s Skull and Bones Club, a secret society for the males of prominent families.

During Bush’s Yale years, his father left the oil business and entered politics in Texas, losing a 1964 U.S. Senate race to the incumbent Democrat Ralph Yarborough. Afterward, George W. was walking across the campus when he saw the famed campus chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, who later became an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War. Bush introduced himself. “Oh, yes,” said Coffin. “I know your father. Frankly, he was beaten by a better man.”

George W. was stunned by such a comment, furious that someone could so easily dismiss the old man. The incident engendered a lifelong distrust of Easterners and began to shape his own political thinking. “What angered me was the way such people at Yale felt so intellectually superior and so righteous,” he says. “They thought they had all the answers. They thought they could create a government that could solve all our problems for us.” At Yale, he adds, many students were plagued by what he calls guilt-ridden thought. “These are the ones,” says Bush, “who felt so guilty that they had been given so many blessings in life—like an Andover or a Yale education—that they felt they should overcompensate by trying to give everyone else in life the same thing.” While Democrats might say that Bush, in his college years, was already becoming elitist, one with little sympathy for the plight of the underprivileged, Bush says that his education only made him want to get back to Texas, as he puts it, “away from the snobs.”

By the time Bush graduated in 1968, his father had been elected to the House of Representatives out of Houston. At the time, it was often said that the elder George had gone into politics only to prove himself to his own father—the same allegation that would later be thrown at George W. But the younger Bush says he never felt any desire, as he got older, to enter public life. “People think we had ponderous political discussions at the dinner table,” he says. “Hell, our family dinners consisted of arguments about sports.”

During his twenties, as his father kept rising in the governmental ranks (ambassador to the United Nations, national chairman of the Republican party, U.S. liaison officer to China, CIA director), George W. carried on what he now calls his cavalier days in Houston. He lived the life of the classic bachelor, driving a Triumph, chasing women, drinking, and never seriously pursuing a career. If he ever seemed cowed by his father’s success, he never showed it. In 1973, when George W. was 26, he got drunk and drove over a neighbor’s trash can. When he was confronted by his father, the younger Bush challenged him to a fight, saying, “You want to go mano a mano right here?”

Standing up to his father might have been part of George W.’s struggle during those years to figure out how to be his own George Bush. He applied to and was rejected by the University of Texas School of Law. He worked for less than a year at a Houston agribusiness company—”A dull coat-and-tie job,” he says—and then he worked for a year in an anti-poverty program. On weekends, he flew F-102 fighter jets for the Texas Air National Guard (his father, of course, had flown a bomber in World War II). It has been reported that Bush mysteriously got ahead of a long waiting list to get into the Guard. When I ask him if he tried to avoid the draft, he grins and says, “Hell, no. Do you think I’m going to admit that? You are out of your mind. Let me give you the political answer, Mr. Reporter”—and then he tells me he wasn’t dodging anything. He says he even asked to be put on an alert program that could have sent him on a three-month rotation to Vietnam, but he was never called.

In 1973, telling no one in his family, he applied and was accepted to the graduate program at the Harvard Business School. “We never knew a thing about it until he just happened to mention to us that he was moving to Massachusetts,” says Barbara. Nor, after Harvard, did he consult his parents about moving to Midland. In 1975 the 28-year-old Bush threw his clothes in the back of his blue 1970 Cutlass and headed west, an eerie retracing of his father’s own move to Midland in a red 1947 Studebaker. “I could smell something happening,” George W. says about Midland in the mid-seventies, and a few years later, another oil boom did hit. With the boom came another generation of young oilmen, many of them childhood friends of Bush who also had gone off to good schools. Now, molded by an upper-class urbanity, they had returned to run their oil companies in button-down shirts and khakis and loafers.

With no job, without the slightest bit of training in the oil business, Bush began working for day wages as a landman, going through courthouse deeds, looking up ownership of mineral rights. His last name did open doors for him: The older leathery oilmen took to calling him Bush Boy and showed him the ropes. Bush soon formed his first company, Arbusto, which is the Spanish word for “bush” and pronounced “Ar-boost-o.” After he drilled a few dry holes, his friends sarcastically began calling the company Ar-bust-o.

George W. was determined to make it without financial support from his family. He lived frugally in a two-room concrete garage apartment, never cooking and rarely cleaning. “His apartment looked like a toxic waste dump,” says Charlie Younger. While he never developed a reputation as a particularly successful oilman—his father, in fact, had been far more adept at finding the gushers during his Midland days—Bush became one of Midland’s great young characters. He was a voracious partyer and beer drinker. One night, he and a friend climbed onstage at the Ector County Coliseum and stood at the back, singing along with Willie Nelson. Bush would go out to dinner at his favorite Mexican restaurant wearing a pair of flimsy black Chinese slippers that he had picked up while visiting his parents in Peking. He dressed so badly (to this day he hates pants with cuffs) that an annual tournament held among friends at the Midland Country Club began awarding a George W. Bush prize to the worst-dressed golfer at the tournament.

In June 1977 he met Laura, the daughter of a Midland homebuilder, and moving fast, “He’s a guy who does not hesitate to make decisions,” says a friend—they were married three months later in a small wedding in front of seventy people. Both were 31. “We didn’t even know he wanted to get married until he showed up at the door with this beautiful creature, Laura, and announced that she was going to be his wife,” says Barbara.

But what really shocked his friends—and, of course, his parents, who once again had no idea of his plans—was his announcement that he was entering the 1978 race for the House of Representatives in a West Texas district that stretched from Midland-Odessa past Lubbock. After 34 years, the incumbent Democratic officeholder, George Mahon, had decided to retire, and Bush, after just two years in Midland, saw another opportunity. If his father’s political ambition was shaped by the idea of noblesse oblige, the obligation of public service among those born in high places, George W.’s was shaped by the idea of carpe diem: Seize the day. Close the deal. Make something happen.

His friends did not know that he even cared that deeply about politics. “They were a little confused about why I was doing this,” admits Bush, “but at that time, Jimmy Carter was president and he was trying to control natural gas prices, and I felt that the United States was headed toward European-style socialism.”

“Were you trying to show people that you too could do something that your dad had done?” I ask.

“Absolutely not,” he says. “Hell, no. I wanted to run.”

“George did sort of leap into it,” says Laura, “but even back then he was smart enough to know that a lot of politics was simply timing. You know, there are a lot of would-be governors of Texas sitting around today who never took the opportunity to get into a race when the time was right. If George is good at anything, it’s timing.”

In what seemed to be a largely amateur effort, Bush recruited his oil buddies, all political novices, to act as his campaign advisers. He never asked his father for help (although his mother did send out a letter to the people on her Christmas card list, asking them to contribute to the campaign).

Bush’s opponent in the Republican primary called him a carpetbagger, a Connecticut Yankee, and a member of the Rockefeller-controlled Trilateral Commission, which, according to the opponent, was trying to take over the world. “I didn’t even know what the Trilateral Commission was,” says Bush, who won the primary anyway. He then lost 53 percent to 47 percent in the general election to the popular Democratic state senator Kent Hance of Lubbock. Near the end of the campaign, the easygoing Bush lost votes when he was accused of loose morals because he had served beer at a meet-the-candidate party for Texas Tech students.

Bush’s strong showing gave him his first taste of the power of the Bush name in Texas. But for the next decade, he barely mentioned politics again. It was as if his congressional campaign had been just another one of his impulsive ventures. He began to concentrate on building his oil business, now called Bush Exploration. “I became totally inebriated with hitting the big one,” he says. He raised more than $2 million from investors but lost most of the money in dry holes. He used to joke that he was “all name and no money.” In 1983, needing more funding, he merged with Spectrum 7, a Cincinnati oil company owned by friends. Bush was president of Spectrum 7 for three years, supervising more than 180 wells, until another oil bust came and prices plummeted, drying up the company’s drilling funds. But Bush landed on his feet again, which critics charge would never have happened if he hadn’t been named Bush. In a stock swap, Spectrum 7 merged with Harken Energy in Dallas in return for more than $2 million worth of Harken stock—a good deal considering Spectrum 7 had lost $400,000 in the six months before the sale. Bush received 200,000 shares of Harken and a seat on the board of directors at a salary of $120,000 a year (later reduced to $40,000).

A few years later, government regulators and investigative reporters would scrutinize every aspect of Bush’s deal with Harken, including reports that he had used his influence at the White House while his father was president to help the little-known Harken win a potentially lucrative contract to drill for oil off the coast of Bahrain. There were also allegations that Bush had conducted illegal insider stock trading in 1990, when he sold his Harken stock, worth $848,560. But a four-month Wall Street Journal investigation concluded that there was no evidence Bush had ever used his political influence to help Harken. Though Bush cannot deny he has received some business opportunities because he is a Bush, he points out that the Harken allegations illustrate the downside of the Bush name. “Look what happened to my brother Neil [who, according to George W., underwent a”completely unwarranted” investigation into his role in Colorado’s Silverado savings and loan scandal, even though a federal court approved a $49.5 million settlement to be paid by Neil and the other Silverado directors]. If you’re a Bush, you’re going to get politically attacked just because of who you are. Damn right it makes me more defensive of the Bush name—and more loyal to it.”

If there is one place where the narrative of Bush’s life turns, it would be at Colorado Springs’ Broadmore Hotel in 1986. Bush, his wife, and some friends had flown there to celebrate his fortieth birthday. He woke up with a raging hangover and announced he would never drink again. He and his close friends and family members say he has not had a drink since.

Those who want to understand a key difference between the personalities of Bush and Ann Richards need only study the way each of them gave up alcohol. Richards went into a twelve-step program, discussing her recovery at length with others, contemplating her deeper emotional needs, studying what she was trying to avoid through alcohol. Bush says he simply got tired of drinking.

“I’m not sophisticated enough to figure out if I had a clinical problem,” Bush says now. “And I can’t say there was something significant that happened to make me change my life. All I know is I was a high-energy person, and alcohol began competing with my ability to keep up my energy level. I wish I could say there was some more profound reason. But I just stopped.”

It was a classic George W. Bush decision. “George is not an overly introspective person,” says Laura. “He has good instincts, and he goes with them. He doesn’t need to evaluate and reevaluate a decision. He doesn’t try to overthink. He likes action.”

Shortly after his decision to stop drinking, Bush also had a long conversation with an old family friend, evangelist Billy Graham, and he began reading the Bible daily. He then moved to Washington to work on his father’s 1988 presidential campaign. Bush family members say the relationship between the father and his firstborn son matured dramatically. Finally, the young rascal—the Yale frat president turned Houston bachelor turned beer-drinking Midland oilman—had grown up. He quickly became his father’s most trusted adviser. When the elder Bush had his children meet the campaign staff for the first time, George W. stood up, looked straight at campaign manager Lee Atwater, and said, “How can we trust you?” For once, the irrepressible Atwater was speechless. “Listen, pal,” George W. said, “if you go to war for our family, we want you completely on our side. We love George Bush, and you better bust your ass for him.”

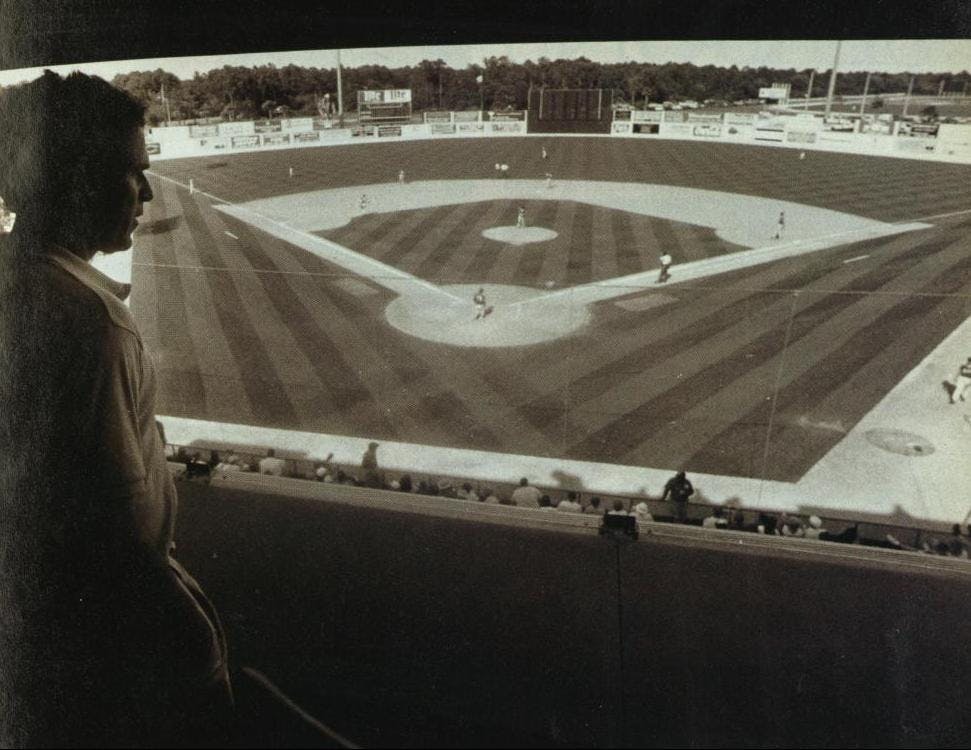

After the election, George W. moved himself and his family to Dallas. He initiated the $85 million purchase of the Texas Rangers, recruited financial partners, and added around $600,000 of his own money (a small percentage compared with the multimillion dollar investments of other investors). As a reward for putting together the deal, Bush received 1.8 percent of the team (worth more than $1.3 million at the time of the team’s purchase) and was paid approximately $200,000 annually to act as managing partner of the team.

Although Bush says there was no political motivation to buy the Rangers—his youthful dream, he says, was to buy the Houston Astros and build an apartment for himself in the right-field wall—the Rangers job did make him a Texas celebrity. During games, he sat near the first-base dugout (never upstairs in a box), signing autographs, chewing sunflower seeds, and getting face time whenever the television cameras would turn his way. (Not all of it was good: During Nolan Ryan’s 300th victory, the cameras showed Bush picking his nose.) He traveled the state on the mashed potato circuit, giving a canned speech about the glories of the Rangers, throwing in a few jokes about the family (“Ladies and gentlemen, I know you wished the most famous Bush could be here tonight.” Pause. “But Mom was busy”).

State Republican party leaders salivated at the idea of Bush’s running for office. He was a natural. So what if he didn’t have a great grasp of state government? The last Republican governor, Bill Clements, didn’t even know the names of most state agencies when he first ran in 1978, and he ended up beating the experienced Mark White. Moreover, Texas voted for Bush’s father during the presidential elections; surely, they would vote for the son too.

Bush did consider running for governor in 1990, then he decided the timing wasn’t right while his father was still president. (Another story has it that the White House vetoed a George W. race because it would be too embarrassing to the father if the son lost.) But the political bug had returned. In late 1991 the elder Bush asked George W. to visit Washington to interview members of the Cabinet about the upcoming 1992 campaign. George W. got the message that White House chief of staff John Sununu needed to go. After talking to his father, George W. spent the night at the White House and the next morning walked into Sununu’s office and came out with his resignation. Some White House staff members were stunned that the coup de grace was administered by such an outsider. But George W. was proving himself to be a savvy political player, the type who would confront people and take stands in a way his father wouldn’t.

In retrospect, George W. says he learned two lessons from his father’s 1992 defeat: Baby boomers were looking for a generational change in leadership, and if you campaign on the status quo, you lose. “People don’t care what you did for them last year,” says Bush. “They want to know what next year is like. Richards is telling people that we’re all getting better because the level of crime has gone down a few percentage points. No one cares about that. Everyone is still scared to leave their homes.”

He also recognizes that Richards, despite her national stardom, is vulnerable simply because Texas is increasingly becoming a Republican state. Republican leaders still believe the only reason Richards won in 1990 was because Clayton Williams turned out to be such a stereotypical good old boy who infuriated many Republican women with his rape-and-weather joke. “George W. Bush is too smart to screw up like that,” says state Republican chairman Fred Meyer. “If you look at results of the 1990 Williams-Richards race [in which Williams lost by less than 100,000 votes], all George has to do is get back the upscale Republican female voters from Houston and Dallas who abandoned us last time—and he wins.” It’s a hopeful analysis: In the past four years, Richards has probably won back her share of Democrats who crossed over to vote for Clayton Williams, and she still has a great following among women, Republican and Democrat.

Nevertheless, George W. Bush, the master of timing, sees the 1994 gubernatorial election as his greatest opportunity of all. He has bought four new suits from the Culwell and Son men’s store in Dallas. He has paid visits to many older GOP fat cats, former supporters of his father’s, some of whom have been skeptical of his candidacy. A few privately say they aren’t sure they appreciate the idea of a Kennedy-like dynasty emerging among Republicans. But supremely confident that “they’ll like me if they just get a whiff of me,” Bush has persuaded the old fat cats to come through. Of the first twenty donors who gave $20,000 or more to the Bush campaign, seventeen were contributors to his father’s presidential campaign.

Most importantly, he has made it to the general election without a primary. (Early last summer, Bush made sure to visit his potential Republican gubernatorial rivals or to take them to a Rangers game to quietly let them know he was going to run and persuade them to dropout—which they did.) Without a primary opponent, Bush had time to develop his platform, which was nonexistent. He also spared himself a bruising fight with an opponent who could have forced him to debate such social issues as abortion or gun control, which might have isolated Republicans on the far right or given Richards more fodder to use against him in the general election.

As Bush began delivering his first campaign speeches in November, he told audiences that he was not running because he was the son of George and Barbara Bush; he was running because he was concerned for the future of his own children. It was a great line. The only problem was that his brother Jeb was also using it in his own Florida gubernatorial campaign. George W. Bush was proving himself to be a terrific campaigner, but a critical listener couldn’t help but wonder if, deep down, Bush was truly prepared for this race.

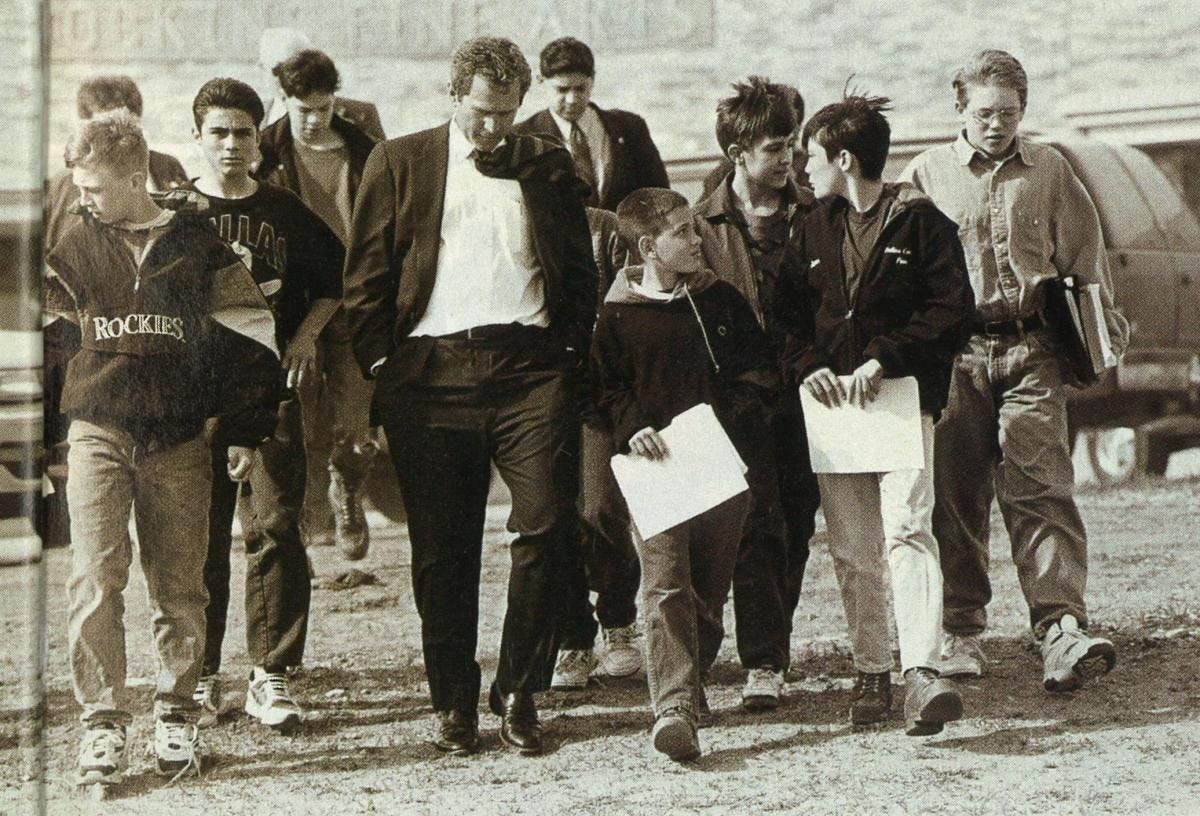

It’s a morning meeting of criminal justice officials in the northeast Texas town of Sherman, and Bush has arrived to pass on his vision of Texas: a state where everyone is, to use one of his favorite words, “accountable.” A state where people alone are responsible for making their lives better. A state with a drastically reduced welfare program, in which benefits are cut off after two years and the recipients forced to go to work. There will be no guilt-ridden Yalies in Bush’s Texas. No William Sloane Coffins. The kind of government Bush says he prefers is one that creates “negative reinforcement” to make people change their behavior. “A governor can’t pass a law to make you love,” he says. “But he can pass a law to protect the innocent, law-abiding citizens from thugs.”

To that end, he is sharing with these Sherman officials his seventeen-point plan to stop juvenile crime, which includes sending especially violent juvenile criminals, even those as young as fourteen, to adult prisons (though segregated from the adult population) for mandatory sentences. “It’s always been normal, when a child turns into a criminal, to say that it’s our fault—society’s fault,” Bush says. “Well, under George W. Bush, it’s your fault. You’re going to get locked up, because we aren’t going to have any more guilt-ridden thought that says that we are somehow responsible.”

A juvenile probation officer challenges him. “We don’t need more juvenile detention facilities,” she says. “We need more rehabilitation for these kids to help them change.”

“Wait a minute,” says Bush, his temper rising—he does not respond well to criticism—”In order to win the war, we’ve got to make these criminals realize we mean punishment. They’ll start changing once they realize they’re going to get punished every time they screw up.”

While Governor Richards, the twelve-stepper, proposes that juveniles undergo more counseling, including heavy counseling for drug addiction, which she calls the major root of crime, Bush wants quick results. He doesn’t think much about the roots of crime. He also doesn’t put much stock in open-ended rehabilitation programs. At Richards’ urging, the Legislature initiated a policy establishing drug treatment in prison—a program that criminal justice experts almost unanimously agree is long overdue in Texas—but Bush will have none of it. He proposes to take $25 million from drug treatment programs in the adult prison system to build more local detention centers for juveniles. “The first priority is building more prisons and getting these criminals off the streets,” he says.

Bush’s approach to crime is indicative of his strengths and weaknesses as a politician. On the stump, his lock-’em-up attitude has great appeal to voters, but it’s naive for him to think the high recidivism rates for criminals will ever drop significantly unless there are strong rehabilitation programs for prisoners used to a life of crime.

As a political newcomer who has spent little time studying government policy, Bush is having to learn as he runs. During a tour of a boot camp in Austin one afternoon, a boot camp official was giving an in-depth report on the variety of vocational classes offered to the young inmates. “Hey,” interrupted a curious Bush, firing a question out of left field, “what happens when one of these fellows decides he wants to punch you?”

Depending on your point of view, it is either refreshing or a little unnerving that a man who might be governor in November is still working out his ideas about what a governor should do. In a meeting earlier this year, he told his group of education advisers (which included former GOP gubernatorial candidate Tom Luce and state Senate Education Committee chairman Bill Ratliff) that he wanted to hear some proposals that would completely undermine the top-heavy Texas Education Agency that controls local school districts. The advisers met among themselves a few times, then came back to Bush. After a one-hour meeting, Bush pulled the trigger and chose the most radical option presented to him: a “home rule” plan that would allow a locality’s voters to declare the locality completely independent from the TEA and set up its own school system, using whatever teaching methods and curricula it chooses. (Districts would have to remain under state school-financing provisions and continue to have to meet certain state-set guidelines for educational achievement.)

Bush envisions schools being run by local school boards that care about education, but it’s at least equally likely that the home-rule plan could lead to endless debate among newly autonomous local school boards over whether to include sex education and school prayer in the classroom. Bush doesn’t seem to have thought much about this. He says he threw out the idea, in part, to get voters to begin thinking more deeply about various ways to reinvigorate public education. In a frank confession, he also tells me he went public with such a plan early in the campaign “because I knew I needed to show myself to be something other than what people project me to be, which is a nice and decent person but maybe not too substantive, maybe a guy who just floated through Yale as opposed to being a leading-edge intellectual.” He adds, “I wanted people to know I cared about ideas and that I was willing to think differently.”

Bush does not deny that there are still gaps in his policies. He talks about increasing the share of state spending for education—thereby shrinking the inequitable funding through local property taxes—but he cannot exactly say where that funding will come from. (The cost of raising the state’s share of education spending from the current 45 percent to, say, 50 percent, would send state spending soaring from $7 billion a year to $8 billion a year.) He says he wants to use his personal persuasive skills as governor to encourage localities to build “tough love” academies for unruly school kids and start mentoring programs for disadvantaged youngsters—but he doesn’t say exactly how he can talk financially overburdened city councils into spending more of their own money without receiving assistance from the state. He vows to overturn a federal court’s infamous Ruiz ruling that has made the cost of operating prisons excessively high—but he doesn’t know yet what his arguments in court would be.

Voters already seem to know he is weak on specifics. At a chamber of commerce luncheon in the little town of Mont Belvieu, south of Houston, an older woman hammered away at Bush with questions about funding for the extra prisons he wants to build. “Well, there’s someone who’s against me,” he told me afterward. Then the woman walked up and asked if she could get Bush’s autograph and take his picture.

For a moment, Bush seemed puzzled, but he understood when the woman said, “I love your father.”

On March 2, Texas Indepenence Day, the former president made a rare appearance for his son. He and Barbara were featured guests at a private $1,000-a-person fundraising dinner at Dallas’ Loews Anatole Hotel. It was a glorious evening to be a Republican from Texas. Around the tables, the crowd was giddy from U.S. senator Kay Bailey Hutchison’s recent acquittal. They talked about how strong she and Bush would look at the top of the Republican ticket in November. The ballroom was filled with polished, professional-looking women in their thirties and forties, exactly the kind of supporters Bush needs to beat Richards.

To thunderous applause, George and Barbara Bush came out behind glittery pink and blue curtains. Then, to even louder applause, out came their son and Laura. For a long moment, Big George and Little George looked at one another. Both were trying to control their emotions. It was “the passing of the torch,” George W. would later say. “For the first time in our family, Dad knew he was not going to be the center of attention. He knew it was another generation’s time.” Finally, the old man shook hands with his son and led Barbara, who had tears in her eyes, to their seats.

After an introduction by Nolan Ryan, George W. Bush stepped to the podium. He looked across the audience toward the center table. It was the first time his father and mother had ever heard him speak publicly. “Mr. President,” said Bush. Pause. “Mom.” The crowd roared. He was off and running, telling jokes about having his father’s eyes …”and my mother’s mouth.” Roar.

It was exactly the kind of speech his father never would have given—affable and irreverent, casual and down to earth. Smoothly, George W. segued into his theme: “This race is really not about me. It is about the desire of everyone in this room to see to it our children can live in prosperity. I’m just the messenger.”

But George W. wanted to make sure this audience knew this race was really all about him. When he got to the line in his prepared text that read, “As sure as I’m standing here, I know we’re going to win,” he said instead, “As sure as I’m standing here, I know I’m going to win.” Even at that moment, he was still fighting to be his own man, someone other than his father’s son.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- George W. Bush

- George H.W. Bush

- Dallas