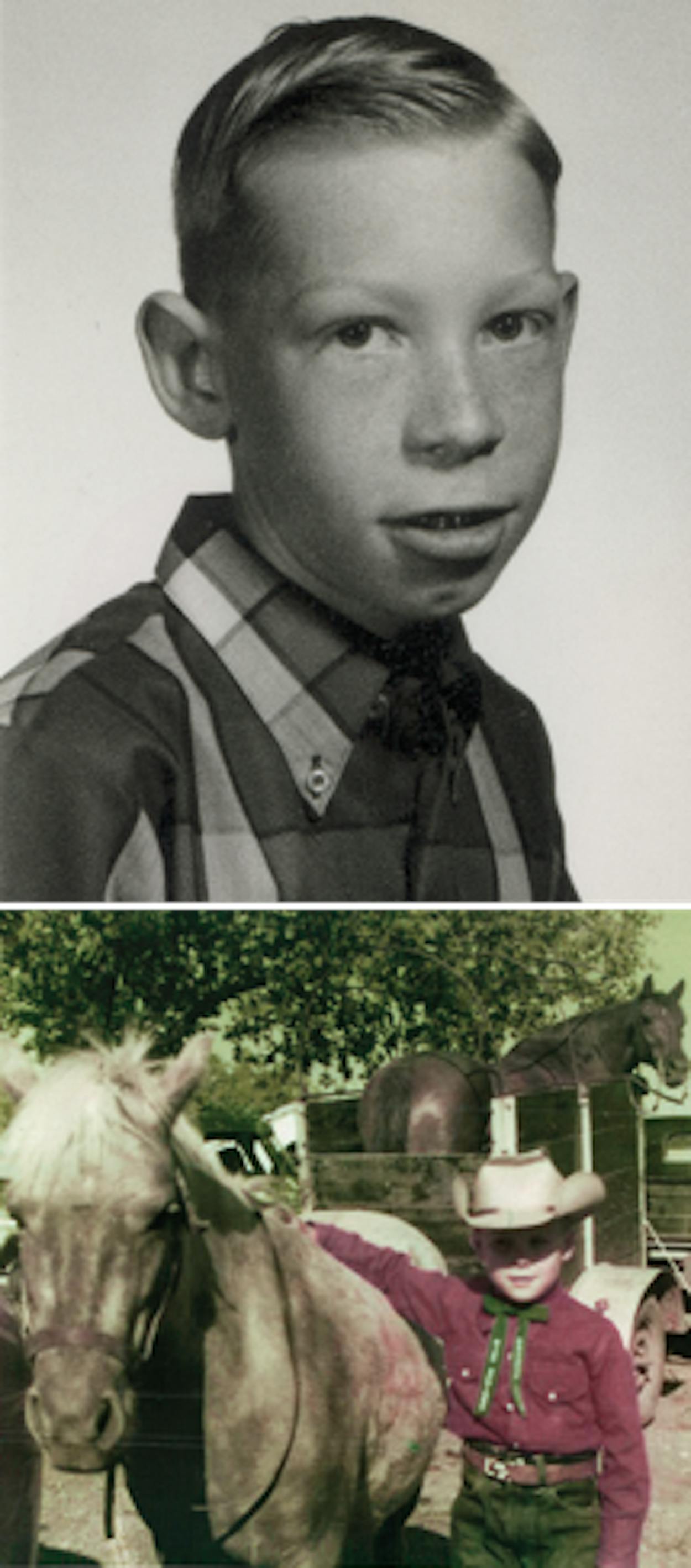

Bill White

I grew up in a house on East Castle Lane, which is one block off Military Highway. Now it’s an upscale area, but back then it was in the country. Until I was in high school my street wasn’t even paved. There were fireflies in the summer and trees everywhere. My dad had two jobs, so during the week he couldn’t get much time, and dinner would be ranch-style beans and tuna fish and a few things that my mom could do and then she’d grade English papers at night. She was a teacher. But Sunday was our family day: Sunday school, church, yard work, throwing around a baseball or football, and watching the ball game while barbecuing. That’s how I grew up.

During the summers, we would go to a lot of baseball games. Dad coached Little League and PONY Baseball. He had some notoriety because he helped form the PONY League in San Antonio and took his team to the PONY Baseball World Series. Our house was full of bookshelves with trophies everywhere. Both of my parents taught Sunday school. They taught me for six years. When I’d graduate to the next Sunday school class, they would graduate and continue to teach me.

There was a lot of church growing up. My mom’s family was fundamentalist Baptist, and my father came from a Methodist family. In fact, when my dad came back from the war, he was recovering from a disability when he met her at Hot Wells Baptist Church. My maternal grandmother insisted that my brother and I be baptized in the Baptist tradition as well as the Methodist tradition so that we wouldn’t lose our souls.

I was also interested in music. I listened to all kinds, from the Beatles—which was a little cutting-edge—to country to classical music. Music was part of the family life. My dad played by ear. We’d have a family band where I’d play the guitar, my mother or my brother would play the banjo, and my father was on the piano. He liked the oldies, like “Danny Boy,” and that was probably the one that we played the most. We practiced a lot. We were always working, doing something. My family didn’t believe in sitting around and watching a lot of TV.

When I was a kid, we always had jobs. For a while I ran the concession stands in the city parks, Elmendorf and Woodlawn and Roosevelt and San Pedro. All of the parks had concession stands. You would get a permit for a corner, and then you would sell snow cones and Cokes and snacks. I really got to know the city, and we ate all over town. Like a lot of active teenagers, I had an early meal and a late meal. The early meal would be at the Whopper Burger at Blanco and 410 and the late meal would be Mi Tierra.

A big change for me came when a friend of my dad’s that we’d known from coaching and bowling got elected to the state Senate in 1966, Joe Bernal. Joe was really active in demanding that people on the West Side got some of the services that people in other parts of San Antonio had. There started being changes in San Antonio politics around then, in the late sixties. There was a group of people who got active in civil rights called the Methodist mafia. People in my church were active in that.

One thing that expanded my horizons was that when I was a junior in high school, I won a national speaking contest sponsored by the American Legion. I’d heard about it because a young man had won it a couple of years before from my town, a fellow whose politics are a little different from mine: His name is Alan Keyes. My dad was his mentor, and he would come to our house. My dad encouraged so many young people to read the newspaper, to read magazines, and even when he was a principal, he would teach a course called current events, where he tried to get people thinking. He didn’t tell them what to think, but he wanted them to be active citizens. About every other week I would go on the road, and the American Legion audiences responded to me and I liked them. They would have me go to state conventions in different states. At the time, there was a lot of turmoil in our country about the Vietnam War, and campuses were erupting. I got to see a lot of the country on that speaking tour.

I was also the editor of the school newspaper. One time there was this heated discussion because a couple of my editorials had a little too much contemporary relevance, so to say. One of them had to do with the female drill squad and whether this qualified as either an academic activity or a physical sport. My opinion was that there ought to be more women’s sports. I thought drill squad was more like “women as ornament.” A drill squad person did not like that. Some parents were upset. The principal insisted that the paper was an extracurricular activity, not some commercial newspaper entitled to First Amendment rights. The journalism teacher supported me, but she said that she didn’t have a good eye for picking up on what might be a little controversial and that if I did write something controversial, she would probably lose her job. So I tried to avoid too many controversial topics after that. As told to Mimi Swartz on April 2, 2010

Rick Perry

I don’t really have a hometown, and it’s just the peculiarity of where I grew up. It’s not a town. It was sixteen miles to Haskell, the closest place that had a post office, and if you went into Haskell today and said, “Rick Perry is a hometown boy,” they’d go, “No, he’s from Paint Creek.” It’s a very broad area but with very few people. For instance, my dad was a county commissioner. This is a county that’s nine hundred square miles, thirty miles by thirty miles, and his precinct was a quarter of that and there were about 350 registered voters.

We lived on a gravel road. If you drove up in May and it had been a nice, wet winter, it could be one of the most beautiful places you’ve ever seen, with wildflowers and green grass, the fields fallow, getting ready to be planted. It could be one of the most beautiful places or it could be one of the most desolate, brutal, uninviting, and uninspiring places. And that was generally a function of the weather.

The people who were adults that lived through the early fifties in West Texas, I think, are some of the most principled, disciplined people in the world, and faithful. Because every day they got up, it was dry. And the wind and the sandstorms. This was before the days of deep tilling, and the sky would become like before dawn in its darkness—and this is in the middle of the day. Huge clouds of dust would roll in from the west. The only time I ever remember seeing my mother cry as a young boy was—they rarely ever bought anything, and certainly didn’t buy anything new, but she had bought a new couch. And there were places in our house that you could see outside through the cracks by the windows, and this dust storm came in and there was a layer of dust all over that new couch. And it just, you know, kind of—it was a hard life for them.

Ours was a little bungalow-style house. It had water that came in, but there was no indoor plumbing in the sense that we think of today. We bathed on the back porch in the number two washtub, and there was an outhouse, and that lasted until ’57, ’58, when Dad built indoor plumbing. We were rich, but not in material things. I had miles and miles of pasture, a Shetland pony, and a dog. I had the best playground you could imagine, but I didn’t have a lot of playmates because we didn’t have neighbors. I can’t tell you where the closest male was that was my age. It would’ve been miles away. There were a couple of young girls who lived, oh, a quarter of a mile up the gravel road. But I spent a lot of time just alone with my dog. A lot.

My dad always referred to that part of Texas as “the big empty.” His family has been out there for multiple generations. They were all tenant farmers. My folks, neither one went to college. My mother worked as a bookkeeper at a gin in Stamford. Dad farmed. When they were building Lake Stamford, he ran some heavy equipment there, but basically he was a dry-land cotton farmer. All the parents in that community worked a lot. But my mother and father were also square dancers. So I sat in lots of National Guard armories, where there would be folding chairs all around the sides, and the kids would be sitting in the folding chairs or talking or outside playing, and the parents were in there dancing. There was a guy who did the calling. His name was Marshall Flippo. Marshall Flippo. I don’t know why that name sticks with me. But he was a renowned square-dance caller. You know, “Skip to my Lou, my darling” and all that. That is the only pastime that I ever remember my parents being involved with.

We were fairly self-sustaining. Mom was a very, very good seamstress and still is. She made my sister’s clothes; she made a lot of my shirts. Now, with blue jeans we wore Levi’s. But when I went to college, Mother still made my underwear.

We had chickens. We milked our own cows, churned our own butter, had a garden, you know. Mother pickled and canned a lot of things and kept them in the storm cellar. Potatoes and different things she would grow and what have you. And we’d probably go to town once a week, on the average, generally on Saturday, to buy the staples, things like beans and flour. Now, Dad had some chickens that he kept in a pen, and I guess they must have been special chickens, may have been roosters, I don’t know what. But one time I let them out because I thought it was cool to watch the dogs chase the chickens, and the chickens got killed. My dad really whipped me. Bad. The worst I ever got in trouble at home was letting those chickens out.

There were three things to do in Paint Creek: school, church, and Boy Scouts. That’s it. And it was plenty. So that community was so close-knit. The scoutmaster was also the superintendent of Sunday school, he taught a Sunday school class, he was also president of the school board. There were two churches. There was a Methodist church and a Baptist church, and they were very intertwined. Methodists sprinkle, Baptists don’t. That’s all the differences that we as kids saw. And you know, the interesting thing for me is that we were no different from anybody else. By and large, everyone was the same. And so, from a “What did you learn in Paint Creek?” perspective, it’s that, you know, we were all equals. As told to Jake Silverstein on March 30, 2010

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Rick Perry

- Bill White