In early January, I contacted the public relations department of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, asking if Mark Cuban, the team’s billionaire owner, would agree to an interview. I received an email from Cuban himself. He wrote that he would be happy to answer some questions over email “as long as we don’t talk politics.”

Huh? Cuban didn’t want to talk politics? One of the more entertaining sideshows of the 2016 presidential campaign was Cuban’s smashmouth attacks on Donald Trump. He lambasted Trump’s intelligence, likening him to a “guy who’ll walk into the bar and say anything to get laid.” He denigrated Trump’s business ventures, proclaiming that his companies were such failures that he must have gone to school at Trump University. He told CNN that Trump was “batshit crazy,” he told the entertainment television show Extra that Trump “gets stupider before your eyes,” and he told Bloomberg Businessweek that Trump displayed “a complete and utter lack of preparation, knowledge, and common sense.”

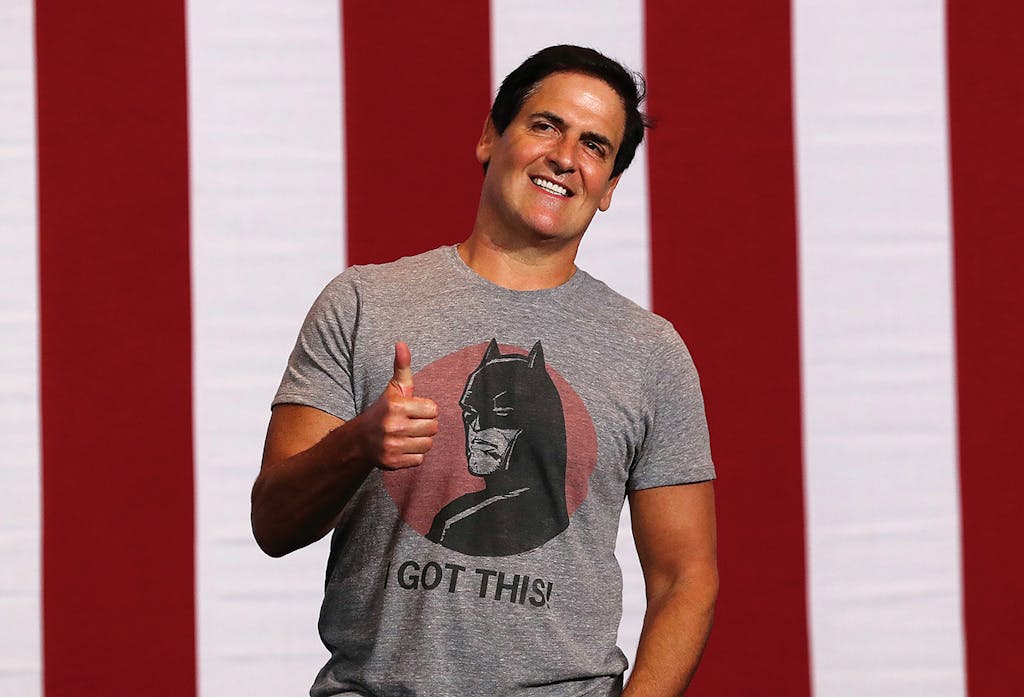

Although Cuban doesn’t belong to any political party, he decided to endorse Hillary Clinton at a rally in Pittsburgh, where he was born and raised. Wearing a Batman T-shirt, blue jeans, and tennis shoes, he jubilantly said hello to the crowd in Russian (his way of mocking the alleged ties between Trump and Russian president Vladimir Putin), and he then launched into a surprising stem-winder of a campaign speech. “Leadership is not yelling and screaming and intimidating,” he declared. “Leadership is having a clear, positive vision. . . . You have to have a thirst for knowledge. You have to be always learning.” Cuban gave the crowd a big, crooked grin. “You know what we call a person like that who screams and yells? What we call them in Pittsburgh? A jagoff. Is there any bigger jagoff in the world than Donald Trump?” The crowd let out an ear-splitting roar.

Since making his fortune in 1999, when Yahoo paid a staggering $5.7 billion in stock to purchase a small Internet company that he co-owned, Cuban has been no stranger to the limelight. Besides the fame that’s come his way as owner of the Mavericks, he’s been a regular guest on the business-television networks, where he weighs in on such topics as stock market trends. He’s a star on ABC’s Shark Tank, critiquing hopeful entrepreneurs’ business pitches. He’s even been a contestant on Dancing With the Stars and played bit roles in movies (in the campy 2015 flick Sharknado 3: Oh Hell No!, he played President Marcus Robbins, who shoots his way to safety when attacked by man-eating sharks).

But his foray into presidential politics brought him a whole new level of public attention. Meet the Press host Chuck Todd was so intrigued by Cuban that he had him on the show. Such unlikely figures as old-school Republican Mitt Romney and consumer advocate Ralph Nader said Cuban should make his own run for president. One of the Washington Post’s political writers, Chris Cillizza, suggested Cuban could be “a potent combination for a candidate—particularly in this sort of anti-politician, populism-first environment.” And James Pethokoukis, a scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, went so far as to describe Cuban as “Trump without the crazy.”

The Clinton people were so taken with Cuban that they invited him to a couple of the Clinton-Trump debates, where he sat in the front row (apparently hoping to distract Trump) and later worked the spin room, making derogatory comments about Trump’s performance. Cuban said he would donate $10 million to a charity of Trump’s choice if he would spend four hours with Cuban discussing policy issues. He told Fox Business that “in the event Donald wins, I have no doubt in my mind the [stock] market tanks.” What’s more, he declared to CNBC, Trump was destined to abuse the powers of the presidency. “The levels to which he would be corrupted by that power are just beyond conception,” he said.

Although Cuban obviously backed the wrong horse—and, so far, the stock market has not faltered—he still remains a source of great curiosity to political insiders. Tim Miller, Jeb Bush’s former spokesman, who is now a partner in a prominent Washington, D.C., public affairs firm, told me that if Trump does not crash and burn over the next four years, there is little chance that a traditional status-quo Democrat, such as a senator or governor, will be able to beat him in 2020. “The only people who I think could go toe-to-toe with Trump are Michelle Obama or Mark Cuban,” Miller said. Mark McKinnon, the former political adviser who co-created and co-hosts Showtime’s The Circus (which covered the 2016 presidential race and just announced a second season), told me that if the Democrats don’t want Cuban because of his more-conservative positions on economic policy, he would have a shot at winning as a third-party candidate. “You need thirty million dollars to get on the ballot in every state, which wouldn’t be a problem for him,” McKinnon explained. “And then he would be wide open to go mano a mano against Trump, making the case that he’s essentially a far better version of Trump, someone who’s a better businessman and who’s also got a much better, more thoughtful grasp on the issues.” McKinnon continued, “If the question for 2020 becomes who can out-Trump Trump, the clear and perhaps only answer is Cuban.”

Yet just two months after the election, I couldn’t get Cuban to discuss politics with me. Why, I emailed him, after making such a mark on the 2016 campaign, was he giving me the silent treatment? “I’m not talking politics,” Cuban promptly emailed back, offering no further explanation.

I took a different tack, asking if he might talk about politics when the NBA season comes to an end this summer. “I’m not talking politics,” he repeated.

I called someone who knows Cuban well. “Has Cuban decided he’s got better things to do than consider the possibility of leading the country?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m totally sure he’s thinking about running for president,” said Cuban’s friend with a chuckle. “It’s too tempting for him not to think about.”

So why then, I pressed, was he not speaking out? “Right now, he’s decided to sit back and let the Trump era play out,” the friend said. “But don’t worry, we’ll hear from him. We’ll hear a lot from him. There’s no way Mark can stay quiet for very long.”

Cuban is a youthful-looking 58 years old—he will be 62 in 2020—with a thick thatch of black hair, a flat stomach, and muscled arms (he works out for an hour almost every day). According to Forbes magazine, he is worth $3.4 billion. He lives with his wife and their three young children in a 24,000-square-foot mansion in North Dallas that has ten bedrooms, thirteen bathrooms, a 1,000-square-foot living room, an eight-car garage, a pool, and a tennis court. He has other residences, in Miami Beach, Florida; Manhattan Beach, California; New York City; and on Grand Cayman. And he owns a couple of jets and a 288-foot yacht called Fountainhead (in a nod to Ayn Rand, his heroine) that has a basketball hoop with a glass backboard mounted over the rear deck.

Cuban is utterly unapologetic about his wealth. “I am the luckiest motherf—er in the world,” he once said. “When I die, I want to come back as me.” For all his possessions, though, Cuban doesn’t really act rich—certainly not the way Trump does. His standard uniform, which he wears almost every day of the week, is a T-shirt, blue jeans or workout pants, and tennis shoes (for Shark Tank, he dresses in a blazer and button-down shirt, but he doesn’t wear a tie). He’s often seen around Dallas ordering a hot dog at 7-11, an omelette at IHOP, or a salad at Campisi’s, an inexpensive Italian restaurant. He takes Zumba classes at Life Time Fitness. At Mavericks games, he has a courtside seat—no owner’s box for him—and he acts like any other rabid fan, pumping his fists in the air and shouting obscenities at the referees, which tends to get him fined by the NBA.

As opposed to other billionaires, Cuban is not shadowed by bodyguards. He isn’t driven by a chauffeur in the mornings to an ornately decorated corporate headquarters. He does almost all his work in a cluttered home office that’s overflowing with autographed basketballs, books, and stacks of paperwork. Although he does have a staff that operates out of a plain brick building in Dallas’s Deep Ellum district, near downtown, he rarely talks to any of them on the phone, and he does his best not to attend meetings.

What he tries to do is conduct all his business through email, which he says saves him valuable time. He reads and writes emails all through the day and into the evening, and it is not unusual for him to answer emails from people he doesn’t know. Last year, a twenty-year-old Ohio man, Peeyush Shrivastava, cold-emailed Cuban with a pitch to invest in his start-up company, which was developing a medical imaging device. Cuban quickly replied, the two struck up an email relationship, and Cuban soon gave Shrivastava $350,000 in seed money to get his company off the ground.

Business journalists like to describe Cuban as a serial entrepreneur. He owns or partially owns more than 150 companies, ranging from Magnolia Pictures (an independent film distributor) to Landmark Theatres (the nation’s largest theater chain) to AXS TV (a cable and satellite television network that mostly broadcasts music videos and rock concerts) to numerous small consumer product firms (like Alyssa’s Cookies, a Florida company that makes high-protein oatmeal cookies) that he first learned about on Shark Tank. (If you haven’t seen the show, entrepreneurs make sales pitches to Cuban and other super-rich “shark” investors who offer up their own money for a stake in the business.)

Despite the fact that he will never come close to spending all the money he already has, Cuban is still looking to get in on the next big thing. Because he believes a growing number of consumers are increasingly disturbed by the lack of online privacy, he has been investing in small firms like Dust (formerly Cyber Dust), which makes an app that, among other things, automatically erases text messages as soon as they are read. Because he believes the day is coming when doctors will be able to diagnose many diseases simply by analyzing patients’ sweat or testing their blood, he has invested in little-known health care technology companies, including one that has created a tattoo patch that reads chemical structures in human skin and another that enables physicians to collect a person’s health care data via mobile apps.

In one of his emails to me, he mentioned that he had just finished reading The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World, by Pedro Domingos, a professor at the University of Washington. Cuban explained that he wanted to learn as much as he could about the technology behind artificial intelligence and machine learning (in which computers are able to program themselves) and then find out “which companies are leading the way”—in other words, which companies are worthy of a major investment from him. “I’m always trying to learn to get an edge,” he wrote.

People who know Cuban love to talk about his ability to guess what the future will bring. “It’s as if he can see around corners,” Todd Wagner, Cuban’s longtime business partner, told me. “He just thinks about things in a different way than the rest of us. When we see half a glass of water, we debate whether it’s half full or half empty. Mark, however, looks at the glass of water and says, ‘Who poured this?’ ”

As a boy in working-class Pittsburgh, Cuban went door to door selling garbage bags instead of flower seeds or Fuller brushes, because he realized that housewives in the neighborhood were always running out of garbage bags. When he got older, his mother, who worked for a real estate company, had a man teach Cuban to install carpet so he would always have a trade to rely on. But Cuban preferred coming up with his own ventures. When the staffs at the local newspapers went on strike, he and a buddy drove to Cleveland to collect copies of the Plain Dealer to resell for a tidy profit back in Pittsburgh.

Cuban’s father, a car upholsterer, told his son that if he wanted to go to college, he was going to have to pay for it himself. Cuban got a student loan to attend Indiana University, in Bloomington, where he studied business and continued his entrepreneurial ways. He made $25 an hour teaching disco dancing to other students, and he took some of his loan money and purchased a bar near campus, which became wildly popular until it was forced to close after Cuban held a wet T-shirt contest and authorities discovered that one of the contestants was a sixteen-year-old girl with a fake ID.

After graduation, he returned to Pittsburgh to work at Mellon Bank but soon quit because he couldn’t stand working for a corporation. For a while, he sold television-repair-shop franchises. In 1982, when he was 23 years old, a couple of his college buddies who had moved to Dallas told him he would love the city’s weather and women. Although he had no job prospects, Cuban threw some wrinkled clothes and a sleeping bag in his ’77 Fiat X1/9 with a hole in the floorboard, drove to Dallas, and moved in with five other guys in a shabby three-bedroom apartment in the Village, a huge singles apartment complex.

He worked for a few weeks as a bartender before taking a job at Your Business Software, a small retail store on Oak Lawn Avenue that sold computer software. Cuban knew next to nothing about computers. But the personal computer revolution was just beginning, and he wanted in. He opened the store each morning, swept the floors, and talked to customers throughout the day. At night, he would lie on the floor of his apartment and read software manuals. When he was fired after nine months—he didn’t open the shop on time one morning because he had stopped by a customer’s office to pick up a payment to the store—he borrowed $500 to start his own company, which he called MicroSolutions. He specialized in connecting the computers at a particular business to a common server (an exotic task at that time), and he modified software to fit the particular needs of that business. He worked ridiculously long hours, seven days a week, often pulling all-nighters. “That’s one of the secrets to understanding Mark’s success,” said Wagner, who before going into business with Cuban had also attended Indiana University and then moved to Dallas to practice law. “He will always outwork you. Always.”

Within a few years, MicroSolutions was doing projects for such clients as Walmart and Zales Jewelers, and in 1990, CompuServe bought the company for $6 million. Cuban was 32. He bought a lifetime fly-free pass from American Airlines for $125,000, traveled the world, and, as he put it, partied “like a rock star.” He took acting lessons in Los Angeles. But in the end, he couldn’t escape his love of business. He began day-trading in the stock market, displaying an uncanny ability to predict which companies (especially those in the tech industry) were on their way up or down. By his account, he made $20 million over the next four years just playing the stock market, and he started looking around to see what he could do next.

In 1995 Cuban and Wagner purchased a controlling interest in a little Dallas company called AudioNet that sought to deliver radio broadcasts of sporting events to pagers—remember pagers?—so that fans could listen to their favorite teams’ games, no matter where they happened to be. Cuban immediately sensed the potential of such a venture, except what he wanted to do was put the broadcasts on a relatively new online networking infrastructure called the World Wide Web, also known as the Internet. He persuaded the owners of a local radio talk station, KLIF, to let him tape its daily shows. He then turned a spare bedroom at his Dallas home into a computer lab of sorts, where he and a couple of programmers encoded the shows and figured out how to transfer them to a website, where they could be replayed over and over. (They were creating primitive versions of “podcasts,” a word that had yet to be invented.)

Cuban and Wagner raised more money, hired a sales staff, and began signing deals with radio stations around the country. Soon, he was hosting live broadcasts on the company’s website (now known as streaming), and within a couple of years, he added video: not only sporting events but music videos, old television shows, even Bill Clinton’s grand jury testimony. The videos were slow to load and the picture often janky, but the website was getting a million hits a day. In 1998 Cuban and Wagner renamed their company Broadcast.com and decided to take it public. Wall Street, which was just getting caught up in the dot-com boom, sent the stock soaring from $18 to $62.75 in its first day. The next year, Cuban and Wagner sold Broadcast.com to Yahoo, and they became billionaires.

Cuban purchased a Gulfstream V jet for $40 million. He bought his mansion for $13 million and moved in with his girlfriend and soon-to-be-wife, Tiffany Stewart, who continued to drive a Honda to her sales job at an ad agency. (For a long time, he didn’t put any furniture in the living room, preferring it be used for Wiffle ball games and Rollerblading.) A basketball junkie, he bought the Dallas Mavericks from owner Ross Perot Jr.—yes, that’s right, the son of Ross Perot, the irascible Dallas businessman who ran for president in 1992 as a third-party candidate—for $285 million, reportedly the highest price ever paid for an NBA franchise at the time. The Mavericks were terrible, with lopsided losing records, and Cuban was not expected to make them any better. When he began racking up fines for screaming at the referees—in one infamous episode he was fined for saying about a ref, “I wouldn’t hire him to manage a Dairy Queen”—New York Post sports columnist Phil Mushnick called Cuban “an attention-starved rich kid” and snarled, “The sports world needs him like it needs a third armpit.”

Cuban, however, completely changed the Mavericks’ culture. He not only paid top dollar for good players, he bought another jet for the team to use, and he equipped every player’s locker-room cubicle with a personal stereo, flat-screen monitor, DVD player, and Sony PlayStation. In 2011 the Mavericks won the NBA championship, and the team’s value leaped to a reported $1.4 billion. Cuban had done it again.

Today, Cuban does short television interviews, and he’ll talk about the Mavericks to sports reporters before home games (he holds those sessions while he works out on a stair-climber machine in the team’s fitness area). But everyone else in the news media has to go through email. His responses to questions are usually brief and to the point. When I asked him about how he was able to oversee so many enterprises, he simply wrote, “I have great people who work for me. I let them do their jobs.” Many questions he ignored. At one point, he wrote to me, clearly impatient, “Let’s part as new friends and stop so that I don’t have to dedicate the rest of my year answering your questions.”

I didn’t take it personally. I knew Cuban was a busy man. Why would he want to spend his valuable time putting up with a nosy reporter who wanted to talk about his political future, a subject Cuban did not wish to discuss?

But for just a moment, let’s consider the possibility of Cuban’s making a serious run for the presidency. Would he in any way be a viable candidate?

Like Trump, Cuban has a big fan base. Besides the five to seven million viewers who watch him each week on Shark Tank, he’s got 6.49 million Twitter followers. He is constantly in demand to give speeches around the country about his sales techniques and business philosophies. (“Work like someone is working twenty-four hours a day to take it all away from you,” he likes to say.) Such business publications as Inc., Success, and Entrepreneur love to write glowing stories about him (“Mark Cuban’s 12 Rules for Startups!” “The Only Mark Cuban Success Strategy Guaranteed to Work for You!” “The Ultimate Maverick!”).

And though he can be exceptionally brash—he loves, for instance, using the f-word—he hasn’t said anything so far that has set off public outrage. (No doubt that is another reason he likes doing email interviews: he gets to control his message.) Nor does he have any past scandals to explain away. (In 2008 the Securities and Exchange Commission accused Cuban of insider trading, claiming he confidentially received negative news about a company from one of its executives and sold his shares in the company before the news was publicly released. But he fought back, angrily accusing the lead government prosecutor of lying, and he was cleared by a jury in federal court.)

Perhaps what is most curious about Cuban as a potential politician is that he has spent a lot of time studying policy issues. Over the years, on his blog and Twitter account, he has written about such diverse subjects as the need to fix but not eliminate the Affordable Care Act, the advantages of initiating a government-funded robotics program to improve the country’s manufacturing plants, and the importance of political leaders’ being more technologically savvy. (“Wars won’t be fought with bombs and bullets as much as bytes and advanced technologies,” he blogged. “Homeland security will be much more about machine vision, learning, and Artificial Intelligence.”) He has said that he’s in favor of a higher minimum wage (but only for those in the food service and retail industries) and a higher capital gains tax. He has suggested that income taxes should automatically go up or down depending on the unemployment rate or some other economic metric. He believes federally guaranteed student loans for college should be cut back, which he thinks will eventually force colleges to lower their costs. (“The biggest drain on our economy today is student debt,” he has said.) He wants the government to stay out of people’s private lives. And he is okay with marijuana being legalized.

But does Cuban truly have the desire to mount a future White House run? During the 2016 campaign, he told one interviewer, “It’s interesting to me. It really, really is . . . I truly believe my ideas are better.” In another interview, however, he said he would never run. “You think I’d put myself and my family through this shit show?”

The problem with that last statement is that Cuban obviously had a heck of a good time participating in 2016’s shit show, playing the role of the Trump troll, calling him a “goddamn airhead” and describing his economic plan as “jibberish.” (My favorite Cuban slam: labeling Trump’s run for the White House as “the Seinfeld candidacy—the campaign about nothing.”) He seemed to enjoy being wooed by a group of prominent Republicans, including 2012 nominee Romney, who wanted him to run as a third-party candidate in hopes of taking away Trump votes and keeping him from winning. When Cuban appeared on Meet the Press, Chuck Todd asked him if he would be willing to be Hillary Clinton’s running mate (this was before Tim Kaine had been chosen). “Absolutely!” Cuban responded.

And there’s no way he can ignore the buzz about his political future, even as a third-party candidate. As McKinnon told me, “People say that a third-party candidate can’t win a presidential election. But they forget that at least for a while, in 1992, Ross Perot was beating George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton, and he certainly could have won if a few things had not gone off the rails. Cuban could win. It just depends on how bad he wants it.”

For most of January, as Cuban stayed silent, I assumed he didn’t want it. But just as his friend had predicted, there was no way Cuban could stay quiet for very long once Trump became president. In the last week of January, Cuban finally let loose, posting dozens of tweets and retweets about Trump’s incompetence. He made the rounds of the cable networks, more than willing to act as the business community’s de facto face of opposition to Trump. He slammed Trump’s Muslim travel ban (“half-assed and half-baked”) and his proposal to put a tax on Mexican goods (“Mexico economy will suffer = more illegal immigrants”). He went after Trump for wanting to spend billions on such infrastructure projects as more roads and bridges (“We need to invest in infrastructure that supports and enables the future, not projects that tie us to a less competitive past”), and, of course, he knocked Trump’s intelligence, tweeting, “It feels like if you spot our president A and B, he wouldn’t be able to find C, He is going to need all of our help. A lot of it.”

It didn’t take long for Cuban to get under the president’s skin. On the morning of Sunday, February 12, while Trump was at Mar-a-Lago, his resort in Palm Beach, hosting the Japanese prime minister, he apparently read a New York Post story sizing up Trump’s potential challengers in 2020. In the story, White House sources acknowledged that their “biggest fear” is Cuban, because he can draw in Democrats, Republicans, and independents. “He’s not a typical candidate,” a White House insider said. “He appeals to a lot of people the same way Trump did.”

I know Mark Cuban well. He backed me big-time but I wasn't interested in taking all of his calls.He's not smart enough to run for president!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 12, 2017

Trump promptly tweeted, “I know Mark Cuban well. He backed me big-time but I wasn’t interested in taking all of his calls. He’s not smart enough to run for president!” Cuban, who clearly had not backed him at all, responded to Trump’s smackdown attempt with a puckish “LOL.” Later, Cuban tweeted about an earlier exchange he had had with Trump, in March of 2016, in which Cuban had written, “You need to dig in and know your shit.” He sent out another tweet in response to someone else’s tweet asking why Trump was tweeting at him. “I don’t know,” Cuban chortled. “But isn’t it better for all of us that he is tweeting rather than trying to govern?”

https://twitter.com/mcuban/status/830781584538218497

When I emailed Cuban to inquire about his return to political discourse, he let me know that he wasn’t completely opposed to Trump. He agreed, for instance, with Trump’s policies regarding “taxes, paperwork, and regulation reduction.” But what bothered him were the same things that had bothered him about Trump during the 2016 campaign: “his inability to manage, communicate, or lead, and his rush to pander to his base.” Cuban went on to write that he was disturbed by Trump’s “lack of situational awareness, understanding of the global balance of power, and his unwillingness to learn.”

So, I asked, given all the controversy that has already emerged over Trump’s presidency, was he giving any more thought at all to running against him in 2020? I sent that email an hour and a half before the Mavericks were to take on the San Antonio Spurs; I assumed I would not hear from him for a while. I figured he was focused on the upcoming game, shaking hands with fans and exhorting his players to do their best. Eighteen minutes later, however, he replied. “I’ll pass.”

I read the words a few times over, not sure exactly what to make of his response. Was he opting to pass on a 2020 presidential run? Or just on answering my question about it? And was he being intentionally vague? Why not just a flat-out no?

I picked up the phone, called Cuban’s friend, and asked if he thought Cuban was already campaigning for 2020. “Not yet. He’s got plenty of time,” said his friend. He chuckled again. “But don’t ever count him out. Cuban’s too good to be counted out. He could very well be the next man of the people.”

Cuban for president. Let the fun begin. LOL.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Mark Cuban

- Dallas