On this night the early returns are favorable. Well-wishers pepper Bush with promises of support as he poses for snapshots and scrawls autographs. The audience listens intently to his after-dinner talk as he refers to himself as “first son” and makes small jokes about giving campaign speeches for his dad (“He won anyway”) and staying at the White House for the Inauguration (“The accommodations are not bad there”). But when he starts talking about running for governor, the crowd slips from his grasp. As he touches on state issues like economic development and education, chair-shifting and throat-clearing muffle his message.

The evening illuminates the problem facing young Bush: how to take advantage of his name and still establish himself as a politician in his own right. The similarities with his father abound. Both went to Phillips Andover prep school. Both went to Yale. Both were pilots. Both started out in the oil business in Midland. Both lost their first political races. Cynics in the Capitol press corps already refer to young Bush as “the shrub.”

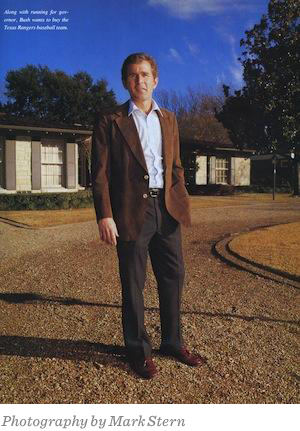

But George W. is quick to point out the differences—starting with his name. Although he was frequently called George Junior during the eighteen months that he served as an adviser to his father’s campaign, the appellation is erroneous: the president is George H. W. Bush. Relaxing in his hotel suite following his Lincoln Day speech, George W. says, “Someone once asked, ‘What’s the difference between you and your dad?’ and I said, ‘He went to Greenwich Country Day and I went to Midland San Jacinto Junior High.’ ” With his coat off, his Bush-for-president tie loosened, and a cigar in his mouth, he displays none of the Eastern courtliness of his father. Family friends say that he is the most Texan of the five Bush children, and U.S. senator Phil Gramm approvingly calls him “a redneck with a good common touch.”

Born in Connecticut, Bush moved with his parents to West Texas at the age of two. His life followed the patterns of many sons of successful fathers: he was close to his mother and modeled his career on his father’s. He was seven years old when his younger sister, Robin, died of leukemia. The family tragedy bonded him to his mother, he recalls. “Mother’s reaction was to envelop herself totally around me,” he says. “She kind of smothered me and then recognized that it was the wrong thing to do.” The family moved to Houston in 1959, when young George was in the eigth grade. He started at Andover two years later, and the family legacy was already weighing heavily on him. Classmate Clay Johnson, now the president of the Horchow Collection in Dallas, says Bush reminisced at the class’s twentieth reunion about how afraid of failure he had been when he first arrived. “He talked about how hard school was,” Johnson remembers. “Yet he had such a sense of duty—his dad had gone there and his uncles—and it was expected of him to hang in there and be tough.” For the first time, but not the last, George W. had to prove himself worthy of being his father’s son.

He went to Yale, as Bushes do. His nascent political skills emerged at a fraternity ritual during his freshman year. Older members were ridiculing the fifty members of his pledge class, claiming that the freshmen didn’t care about each other. To prove their point, the upperclassmen demanded that each freshman name all of his fellow pledges. No one came close—until George named all fifty.

After Yale he followed the Bush pattern of public service: military duty (flying F102s), electoral politics (his father’s 1970 Senate campaign), and good works (a job with a Houston organization in which professional athletes worked with Third Ward children). Then he went back to the East Coast, getting an MBA from Harvard before returning to Midland in 1975 to do what his father had done before him—start his own oil company. “It was just obvious that Midland was the place for me,” he says.

He did it without family money. Raising cash from investors, he formed an energy company eventually called Bush Exploration. It was successful but small by Midland standards. “I’ll be the pauper in the governor’s race. I’ll be the one hollering and screaming that they’re tyring to buy it,” he says jokingly. He married Laura Welch, a local school librarian, in 1977 following a three-month romance. In a town of rich oilmen, the Bushes lived in two modest brick houses, moving to the second after twin daughters were born in 1981. Neighbors describe him as an involved father, behind the video camera at birthday parties or building snowmen with his daughters—a down-to-earth sort who knocked around the yard in shorts and bare feet. When a friend’s wife was seriously ill with leukemia, he took their kids out for ice cream and ball games. Once he spent a week painting a friend’s new house.

In 1978 Bush again followed his father’s pattern: he entered politics. Motivated, he says, by a strong antipathy for Jimmy Carter, he ran for the congressional seat being vacated by George Mahon of Lubbock. Bush was the underdog in the Republican primary to former Odessa mayor Jim Reese, who had run a strong race against Mahon previously. In a district that ran from Midland to Lubbock, Bush carried only his home county—but that was enough. In the general election he faced Kent Hance, then a conservative Democrat but now a Republican and a likely Bush rival for hte governorship. Hance ran as the true Texan in the race, proclaiming that “Yale and Harvard don’t prepare you as well for running in teh nineteenth congressional district as Texas Tech does.” He also criticized Bush for accepting out-of-state contributions. Bush was reduced to complaining about low blows. “We have been attacked for where I was born, for who my family is, and where my money has come from,” he said at the time, adding—in the best Bush manner—”I don’t think that’s fair.” Bush ran a credible race, but Hance won with 52 percent of the vote.

After his loss, George W. found himself becoming more involved in religion. For once he departed from his father’s course. Notwithstanding his family’s Episcopalian tradition, he joined the Methodist church after his marriage. Now he had come to take the Bible more literally, and at lunch one day he told his mother of his new fervor. He said that he felt a person must believe in Jesus Christ to attain salvation; the Bible was explicit on that.

What about Jewish friends or Arab friends who have led exemplary lives, Barbara wanted to know.

“I can’t refute your logic. I’m just telling you what the Bible says,” George answered.

His mother got up from the table and called Billy Graham. “Graham’s answer was wonderful,” George W. recalls. “He said something like, ‘Barbara, one of the things I learned is never to play God. A human being’s role is not to sit around determining who goes to heaven or who doesn’t, but to take what you can from your own religious experience and live according to it.”

“The answer for me as an individual is to exercise my choice and free will and let others do what they need to do.”

In business, unlike religion, George W. stayed close to the path his father had established. While the rest of Midland was riding the oil boom, he didn’t go deeply into debt—displaying the same cautious instinct that had kept his father from gambling heavily on offshore exploration in the sixties. When oil prices began skidding in 1986, George W. was one of the few oilmen who was well placed to sell out. He sold the company to Harken Energy in return for Harken stock, and today he holds around 300,000 shares, worth nearly $1.5 million.

With the sale of his company, George W. was at loose ends. He moved to Washington to work in the presidential campaign, playing the role of family spokesman and surrogate for the candidate. While reporters were questioning the elder George’s toughness, the younger George was earning a reputation for feistiness. He engaged in a shouting match with a network cameraman, and when Newsweek ran a cover about “The Wimp Factor,” George W. delivered the family’s angry protest. He says that the greatest lesson he learned from the campaign is to have fun as a candidate—to let today’s barb, today’s ugly characterization be gone tomorrow.

“I learned that from the man himself,” he says. “He doesn’t let the ugly side of politics bother him.” The statement is replete with unintended irony, since the Bush campaign against Michael Dukakis did not exactly take the high road. The 1990 governor’s race isn’t likely to win any awards for sportsmanship either. Republicans have learned the hard way—from losing elections like George W.’s race against Kent Hance—that playing rough works. Republican national committeeman Ernie Angelo of Midland says that Bush’s 1978 defeat was a “case of two nice guys running against each other. We always lose those races, no matter who the candidate is.”

The Republican field is already crowded with big names and big money. In addition to Hance, now a railroad commissioner, possible candidates include Secretary of State Jack Rains of Houston, unconventional oilman Clayton Williams of Midland, and corporate raider T. Boone Pickens of Amarillo. Some Republicans worry about the prospect of an “all-junior” ticket—Secretary of Commerce Robert Mosbacher’s son, Rob Junior, is looking at a race for lieutenant governor. But the most important issue in Republican primaries is the ability to win in November, and George W. is convinced that he comes out on top.

“If I run, I’ll be most electable. Absolutely. No question in my mind,” he says. “In a big media state like Texas, name identification is important. I’ve got it.”

Just as his father relied on symbolic issues in his campaign, George W. speaks vaguely about his political agenda for Texas. Like his father, he says he sees politics as a higher calling. “I want to affect the lives of people,” he says. “I want to make life better. I think politics is an arena where you can do that.”

His reaction to issues is largely ad hoc and, despite extensive briefings by Republican legislators, somewhat uninformed. In his Lincoln Day speech he endorsed allowing children to attend any school within a school district; afterward, he admitted that he did not know how his plan could be implemented and still be consistent with court orders for desegregation.

After Bush’s speech a local reporter asked him whether he saw himself as part of a political dynasty. “That implies you inherit something,” he answered. “I tried to shake every single hand that was here, and I’m not afraid of hard work. The concept of dynasty just doesn’t exist. If you mean political tradition, then yes.”

Later he brought up the subject of a dynasty again in private, comparing the Bush family with the Kennedys. “They never had to work,” he said. “They never had to have a job.” It is one difference, but not the only one. The Kennedys, like Ronald Reagan, embody a specific set of beliefs about the role of government. But George H. W. Bush rose to be president of the United States not by working for specific goals but simply by being ready to serve when called. In that regard, and in many others, the son mirrors the father.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush

- George H.W. Bush

- Midland

- Houston