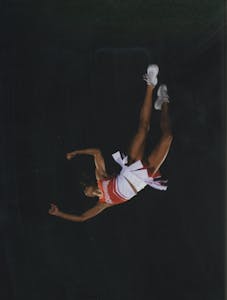

THEY HAD NAMES LIKE KAYLEE AND HAILEY and Ashley and Brittany, and they all had long legs and glossy hair and tan summer skin. More than a thousand of them—1,345 cheerleaders from across Texas—had come to Southern Methodist University, in Dallas, on a sticky afternoon in June for the first day of cheer camp, and a clutch of mothers and squirming little sisters was taking in the view. On the lawn outside Dallas Hall, girls in starched cheerleading uniforms the bright colors of LifeSavers built pyramids and performed midair toe-touch jumps and a dizzying number of standing back handsprings; the nimblest ones were lifted ten feet off the ground, where they each wobbled on one leg, grinning, before dropping into the outstretched arms below. Clipboards in hand, an army of clean-cut instructors from the National Cheerleaders Association stood watch, taking notes and appraising them, as the girls offered encouragement to one another (“Awesome job, Bailey!”). At the end of the day, they dusted themselves off and walked arm in arm to their dorm rooms, smiling and clapping and, of course, cheering. As they made their way across campus—We’ve got spirit. Yes, we do!—a thousand ponytails swayed back and forth.

I had come to SMU in hope of understanding what it was about cheerleading, exactly, that had sparked such hostility just a few weeks earlier at the Texas Legislature. While pressing issues like balancing the budget and financing public education had been put on hold, the House had found the time to consider HB 1476, or “the booty bill”: legislation that prohibited cheerleading squads, marching bands, and dance and drill teams from performing at public schools “in a manner that is overtly sexually suggestive.” The bill, which inspired an intense, two-hour floor debate that included the spectacle of legislators shaking pom-poms and blasting KC and the Sunshine Band’s “Shake Your Booty,” had been ridiculed in newspapers (“Bunch of Sis, Boom, Baloney!”) and on cable news and late-night talk shows. “You wouldn’t have the Texas Rangers out there busting the cheerleaders and putting them in cuffs, would you?” Bill O’Reilly asked the author of the legislation, Houston Democrat and lay preacher Al Edwards, on The O’Reilly Factor. The Daily Show piled on with a segment called “No Child’s Sweet Behind,” which featured correspondent Bob Wiltfong bumping and grinding during an interview with Edwards. “Is it any wonder Texas has become a national punch line?” marveled Austin American-Statesman columnist John Kelso, who suggested that the Legislature create a watchdog group to monitor cheerleading and call it the Bipartisan Observational Organization on Booty, or BOOB.

But a majority of lawmakers, who voted to pass the bill, failed to see the humor in it. During the floor debate in the House, Republican Carl Isett, of Lubbock, called for a return to “old-fashioned morality,” citing sexually suggestive cheerleading—along with out-of-wedlock births and throwaway marriages—as evidence of the moral decay of our time. “If I take my twelve-year-old son to a high school football game, I don’t want to have to cover his eyes when the cheerleaders are on the field,” he said. Linda Harper-Brown, a Republican from Irving, praised the bill as “a shot across the bow” for school districts, which would have lost funding under its provisions if they did not ensure that their cheerleaders’ routines were sufficiently wholesome. Representative Edwards went so far as to suggest a link between “overly sexy performances” on the sidelines and a host of social ills. “We see, as a result, more of our young girls getting pregnant in middle and high school, dropping out of school, having babies, contracting AIDS, herpes, and cutting off their youthful life at an early age,” he said. “And members, it’s part of our responsibility to do something about it.” While legislators who opposed the measure criticized it for being everything from a sexist bill (no one was regulating football players’ behavior) to a publicity stunt, the rhetoric from supporters—which included the local chapter of Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum—seemed to suggest that cheerleaders posed a threat to the moral fiber of the children of Texas every time they walked onto a football field.

That cheerleading, of all things, found itself in the crosshairs of a culture war was unlikely enough; that it happened in Texas, which introduced the world to the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders 33 years ago, was stranger still. In the end, the booty bill failed to reach the governor’s desk; the Senate refused to consider HB 1476, and it died before the end of the regular legislative session. The House succeeded only in passing a resolution that called on the Texas Education Agency to monitor school performances for sexual content. No videotapes of raunchy cheerleading routines ever surfaced, and even Edwards was hard-pressed to name a school whose squad had crossed the line. But the stigma has lingered. Just before the start of the school year, Texas Education Agency commissioner Shirley J. Neeley sent a memo to every superintendent in the state, directing them to monitor their districts’ cheerleading squads, marching bands, and dance and drill teams for any “overly sexually suggestive” routines and cautioning that “inappropriate performances are unacceptable and should not be tolerated.” It was a strange imperative, given what I had seen that summer day at SMU, when girls had whiled away an afternoon reciting upbeat cheers. Then again, it has been a long journey from pleated skirts and saddle shoes to accusations of indecency. Why, when cheerleading is more popular than ever, have our feelings about it grown so complicated?

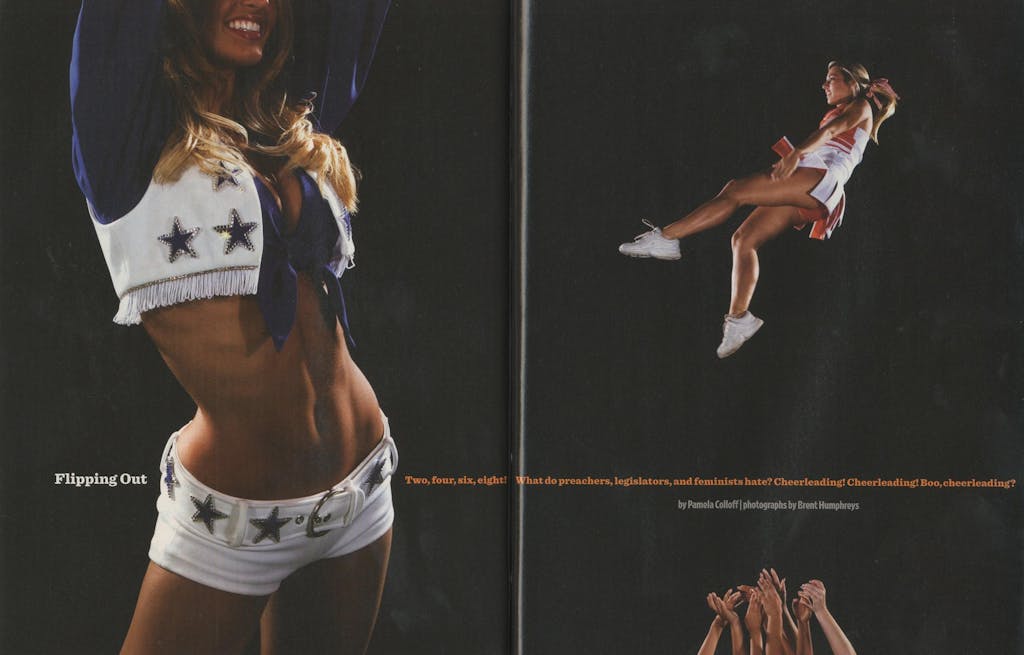

IF THERE WAS A MOMENT IN HISTORY when sex became forever associated with the sidelines, it happened on the hot, humid afternoon of September 17, 1972, when the brand-new Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders—seven professional dancers who Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm had promised would add a “touch of class”—paraded onto the field at Texas Stadium in front of 55,850 spectators, wearing only hot pants, go-go boots, fringed vests, and satin blouses tied snugly above the midriff. Part Vegas showgirl, part girl next door, the women wore royal-blue-and-white uniforms that allowed for plenty of jiggle and signaled the start of a new way of seeing the cheerleader in the public imagination. (Until that fall, the Cowboys’ game day entertainment had featured the CowBelles and Beaux, a group of local high school students who had worn matching varsity sweaters and performed pom-pom routines.) Just as Schramm had intended, his new squad soon had Dallas talking; breathless news reports speculated, contrary to fact, that the cheerleaders were not wearing bras under their trademark blouses. “We were an overnight phenomenon,” remembers Dixie Luque, a member of the original squad who is now a real estate agent in Plano. “When we came off the field, there were fans waiting at the end of the ramp wanting our autographs and gentlemen throwing roses from the stands, asking if they could take us to dinner. And you’ve never seen so much mail! None of us imagined—we were just a bunch of girls who loved the Cowboys and loved to dance. I mean, who would have thunk?”

Of course, the cheerleader had always been an object of desire; she was the unattainable girl at the top of the high school caste system, the prettiest one in the class. The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders were not technically cheerleaders—they didn’t cheer—but their name evoked those old associations and only magnified them. Coming at the height of the women’s movement, their uncomplicated brand of femininity held monstrous appeal, though it wasn’t until January 1976, when the Cowboys played the Pittsburgh Steelers in Super Bowl X, that they secured their reputations as national sex symbols. TV cameras rarely focused on the sidelines then, since professional cheerleading squads were still a novelty; the Steelers had no one other than their fans to cheer them on. But during a break in the game, a cameraman let his gaze wander to the edge of the field. Gwenda Swearengin, the former Miss Corsicana contestant—turned—Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader who had caught his eye, looked back—and winked. Seventy-five million viewers across America were watching. And so, as the story goes, the first pinups of the gridiron were born. Soon there were swimsuit calendars, made-for-TV movies, Love Boat cameos, shampoo commercials, and public appearances with thousands of screaming fans. The cheerleaders were so popular that in 1977 their cheesecake posters outsold Farrah Fawcett’s.

The Cowboys franchise traded on the squad’s all-American, mass-market eroticism, at the same time careful to keep its image squeaky-clean. Cheerleaders were not allowed to fraternize with players, perform where alcohol was served, smoke cigarettes while in uniform, or even chew gum on the field. They were, after all, “America’s Sweethearts.” To drive the point home, their director, Suzanne Mitchell, reeled off a list to a Dallas Morning News reporter of all the dignified jobs her girls were busy holding down when they weren’t high-kicking at Texas Stadium. “They’re teachers and secretaries, P.E. instructors and stewardesses,” she told the paper in 1977, adding, “We don’t pick these girls up at go-go joints.” The success of the squad required its image to remain above reproach; after the release the following year of the X-rated film Debbie Does Dallas—which featured a group of cheerleaders trying to finagle a trip to Big D so they could audition for a squad whose blue-and-white uniforms looked awfully familiar—the franchise sued for a trademark violation and won. When Jerry Jones announced in 1989 that he wanted to outfit the squad in halter tops and spandex and relax the rules that kept cheerleaders from socializing with players, more than a third of them quit, complaining that the team’s boorish new owner was trying to undermine their “traditional virtues” and “high moral standards.” (“I feel like we are a sacred, sacred organization,” one cheerleader said.) Jones eventually backed down.

These days, the 37 women who are the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders spend much of their time at the team’s headquarters, in Irving, in a chilly dance studio with blond-wood floors and mirrors that extend from floor to ceiling. On the wall is a list of aphorisms that urge them to be better: “Wear a cheerful countenance at all times.” “Look at the sunny side of everything.” “Give so much time to the improvement of yourself that you have no time to criticize others.” On the opposite wall stands a scale. Outside, the foyer is lined with blown-up swimsuit calendar photos in which cheerleaders are pictured in tiny bikinis crawling on all fours across expanses of sand or running their hands through their sea-soaked hair or arching their backs at the water’s edge. The women who are picked to be Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders—more than a thousand audition each year for the honor—must still adhere to the same strict code of conduct and be able to dance for upwards of four hours in sweltering heat (longer, if the game goes into overtime) without ever letting their smiles falter. Each cheerleader must attend rehearsals at least four nights a week and stay at her audition weight or risk getting cut from the squad, a rule enforced with occasional weigh-ins; she must also reaudition for her job at the end of the football season. Although the pay has risen from $15 per game to just $50, no one is complaining. “It pays for gas and panty hose!” one cheerleader told me. “Pretty much every girl who’s come through these doors saw the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders on TV when she was a little girl and knew that’s what she wanted to be when she grew up,” explained former cheerleader Courtney Sparks, who recently retired from the squad. “This is a childhood dream.”

I had visited the dance studio that July afternoon to ask the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders what they thought about the debate over cheerleading. Carefully sidestepping any questions about politics, Laura Beke and Elizabeth Davis sat and talked with me, emphasizing that they and their fellow squad members were always mindful to be “ladies” and “role models” and were proud to be part of “a classy organization.” “We wear more clothes than most people do on the beach,” offered Beke. Several other cheerleaders—women in their early twenties with perfectly sculpted bodies and manes of blond hair—were busy teaching DCC Camp, the cheer and dance instruction that the squad gives to local girls each summer. Over the thumping beat of RuPaul’s “Looking Good, Feeling Gorgeous,” the cheerleaders stood in front of the bank of mirrors, counting to the music (“Step five, six, seven, eight!”) while they effortlessly walked through a dance routine. Behind them, a motley crew of junior high school students—girls with mouths full of braces, pudgy girls with acne, flat-chested girls who hadn’t hit puberty yet, girls with frizzy hair and glasses—watched in rapt amazement. Studying themselves in the mirror with fierce concentration, they tried to follow along. They thrust their chests forward and swiveled their narrow hips back and forth, awkwardly aping the cheerleaders who were dancing in front of them, trying for all the world to look like someone’s idea of sexy.

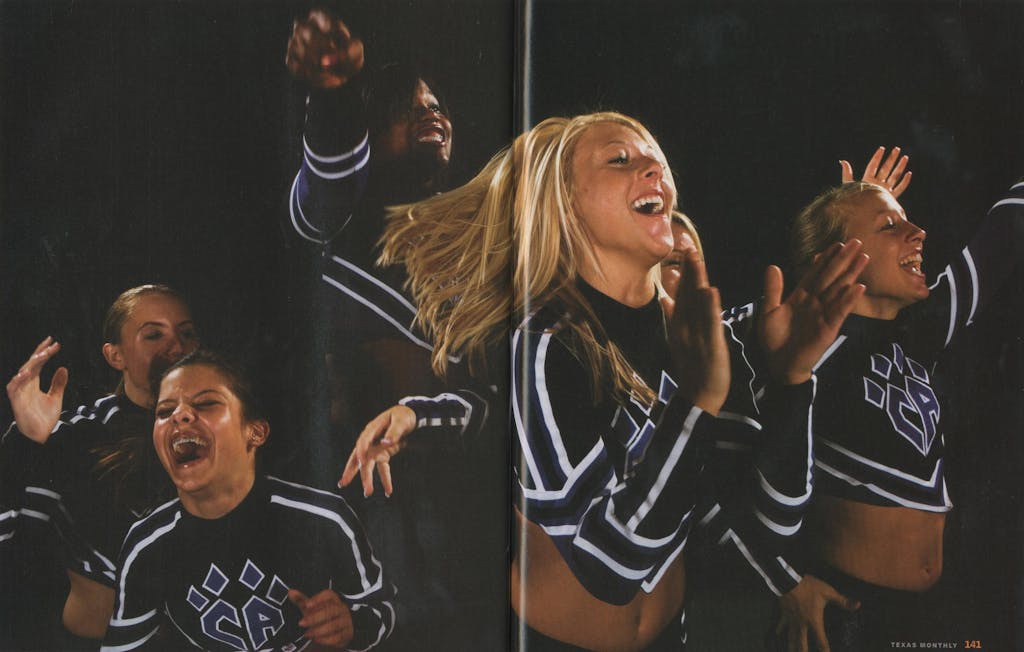

SEVENTEEN MILES NORTHEAST of Dallas is the suburb of Rockwall, a mostly white, middle-class enclave of big-box stores, chain restaurants, and subdivisions that, as one resident observed during my visit, might more aptly have been named Wonderbreadland. Although its 5A football team, the Yellowjackets, has for years maintained a near-perfect losing streak, its varsity cheerleading squad has given Rockwall something to brag about. In January the girls won second place at the National Cheerleaders Association’s annual competition, where they came in just three one-hundredths of a point behind the Kentucky high school that cinched the title in their division. Rockwall’s success was not unexpected; most of the girls on the squad have taken cheer and gymnastics lessons since they were in kindergarten and can perform the most demanding stunts with such grace and ease that even when they are spinning in midair ten feet above the ground, they seem to be doing nothing more demanding than breathing. The eighteen-member squad includes two sisters, Hannah and Caroline Wilson, whose great-grandmother, Chug Linn, cheered for Rockwall during the 1930-31 school year. Before she died this summer, Linn was able to recollect little of her life through the fog of Alzheimer’s, but she never forgot the Rockwall High School fight song (“For the boys, we’ll yell and yell and yell!”), which she would recite faithfully, from start to finish, whenever she was given the opportunity.

Rockwall’s first game of the season, against the North Garland Raiders, featured none of the provocative sideline moves that had caused so much hand-wringing in Austin. As the Yellowjackets tried to move the ball that August evening, their cheerleaders did back handsprings down the length of the field and stood on the sidelines urging the team on, shouting in unison: “Go orange! Go white! Go ’Jackets! Fight, fight, fight!” Their uniforms were not what one would wear to church on Sunday, but they were hardly offensive, either; a fitted top covered the midriff, and a flouncy skirt, which grazed the top of the leg, was worn over black spandex shorts that revealed nothing more than a pair of well-toned thighs. Climbing onto one another’s palms, the cheerleaders ran through their repertoire—soaring above the field in arabesques and scorpions, bottle rockets and basket tosses—while the boys battled it out on the field below. (Overcome by the heat, the Yellowjackets’ mascot periodically dashed off the field to remove her enormous plush-covered head and gulp down water, wiping the sweat from her face with her furry orange arms.) When one of Rockwall’s players suffered an injury and lay grimacing on the 40-yard line, each cheerleader knelt at the edge of the field and looked appropriately solemn. And during the third quarter, when the team needed a little extra encouragement, they leaped into the air again and again with broad smiles, yelling “Let’s go, Rockwall!” In spite of their efforts, the Yellowjackets still lost, 20—17.

Sitting on the yellow school bus that ferried them to and from the game that evening, the girls talked about their frustration over the way cheerleading had been maligned this spring. “We’re not trying to offend anyone,” Hannah Wilson said. “I mean, the worst thing you can say about us is that we all like to be the center of attention.” Perhaps mindful of the image that they wanted to project, the girls talked at length about the church missions they had participated in, the most recent of which had taken several members of the squad as far as Ghana. “We are truly, truly blessed,” one girl told me. Their sponsor, an upbeat English teacher and former cheerleader named Holli Loveless, drove the point home. “Cheerleading has always tapped into issues like sex and power, but these girls are morally strong,” she said. “They are well rounded in their family lives and spiritual lives.” The squad was particularly exasperated by the way that one of its members, Kristin Turner-Wurm, had been portrayed this spring in the Dallas Morning News’ free spin-off, Quick; a front-page article on HB 1476, which ran under the headline “The Dirrty Rule,” was accompanied by a photo of her performing a stunt in a sports bra. The image had been taken out of context, she explained; she had been photographed practicing at Cheer Athletics, a Garland gym that is famous not only for turning out winning squads but also for toughening up its cheerleaders by making them practice without air-conditioning. “I don’t wear a sports bra when I perform. I wear a uniform,” she said. “They made what we do look bad.”

As the school bus made its way back to Rockwall, the cheerleaders passed around bubble gum and sent text messages to one another in the dark. One girl hunched over a binder, doing her homework by the light of her cell phone. The sound of pop culture filtered through the conversation now and then, as when one girl started singing the Black Eyed Peas’ hit “My Humps” (“What you gon’ do with all that junk?/All that junk inside your trunk?”). But when the bus swung into the Rockwall High School parking lot, the girls all chimed in:

Hail, dear old Rockwall!

How we love you

Ever you’ll find us

Loyal and true.

When they had finished, head cheerleader Bronwyn Hill stood up and yelled, “Make sure to tell the guys they had a great game!”

IN A SIMPLER TIME, before anyone had heard of the booty bill, a Texan named Lawrence Herkimer got the idea to fasten dyed crepe-paper streamers to the end of a wooden stick. He called his invention a pom-pom. (Later, when he discovered that the term meant something rather crude in Hawaiian, he changed it to “pom pon,” but the original name stuck.) In 1956 he and his wife began making pom-pom kits out of their garage in Dallas, and girls across the Southeast soon started clamoring for them. After Herkimer applied for a patent, the uniform business he owned, Cheerleader Supply Company, started producing pom-poms wholesale. And so the cheer industry was born.

“Mr. Cheerleader,” or just “Herkie,” as the 79-year-old Herkimer is called, is credited with creating everything from cheer camp to the spirit stick and for turning Texas into the cheerleading capital of the world. He conceived of his most imitated invention—the herkie—during World War II, when he was a cheerleader himself at North Dallas High School. (The herkie, which involves thrusting one leg forward in midair while crooking the other back at the knee, is still a sideline perennial.) While an undergraduate at SMU, Herkie conducted the first-ever cheer clinic, teaching 52 girls at Sam Houston State University, in Huntsville, the art of public speaking, gymnastics, and rhyme; it was so popular that he made it a fixture at SMU and then at colleges around the nation. When he founded the National Cheerleaders Association in Dallas more than half a century ago, he launched the city’s reputation as the epicenter of all things cheerleader. Herkie has since retired to Miami Beach, where he isn’t quite as limber as the day he performed 38 backflips for a Cheer detergent commercial. (Doing a herkie now, he joked over the phone, would require “a crane and some piano wires.”) On the subject of the Legislature and HB 1476, which I asked him to weigh in on, Herkie was philosophical. “There have always been humorless people,” he said. “They made the same complaints fifty years ago: ‘These girls need to cover up—they’re half-naked’ or ‘It’s disgusting how they are throwing their legs apart.’ You can read something ugly into anything, you know.”

Cheerleading has changed since the days when Herkie taught girls to do pom-pom routines to the tune of “Lollipop.” The technical skill and athleticism that are required by squads like Rockwall’s have made cheerleading more than just a popularity contest. At many 4A and 5A high schools, the baseline at tryouts is no longer poise or a pretty face; it is a rounded-off standing back handspring, a technique that only students who have had years of practice in gymnastics can execute. (Splits and cartwheels went out of fashion around the same time as Keds, feathered hair, and “How Funky Is Your Chicken?”) Routines have become so dazzling now that one annual competition is broadcast on ESPN. The acrobatics have come at a price; in the past 22 years, cheerleading has accounted for more than 50 percent of catastrophic sports injuries—that is, injuries involving hospitalization or death—among girls in high school and college. At cheer camp, where instructors stress the importance of safety, it is not uncommon to see girls in splints, hobbling around on crutches, or occasionally pushing the least fortunate member of their squad around in a wheelchair (bedecked in the squad’s school colors, of course). Early last year, a cheerleader at Prairie View A&M University was paralyzed from the neck down when her squad failed to catch her after throwing her in the air.

Because modern cheerleading is so physically demanding, many of its boosters think it should qualify to be a sport in its own right. But just as calling the Miss America pageant a “scholarship competition” elicits eye rolls and snickers, so too does the “Cheerleading Is a Sport” slogan that is emblazoned across so many girls’ T-shirts. School districts have been slow to recognize cheerleading as an activity that is on par with other girls’ sports. If anything, cheerleading suffers from a double standard; while some administrators are “grounding” squads—forbidding their members to perform stunts as a way of heading off accidents— no school districts have benched their football teams as a safety precaution. And so cheerleaders find themselves in a catch-22; the more they ask to be taken seriously, the more dismissive their critics become.

Their detractors have included feminist theorists and academics, who have weighed in with essays like “Postmodern Paradox? Cheerleaders at Women’s Sporting Events” and “Hands on Hips, Smiles on Lips! Cheerleading, Emotional Labor, and the Gendered Performance of ‘Spirit.’” Why, they ask, should girls participate in an activity that still requires them to wear hair ribbons, lipstick, short skirts, and happy faces when Title IX long ago opened up other opportunities? Waving pom-poms at football games was one thing in the fifties, when chanting “Two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar” provided the only chance for girls to participate in school sports, but another thing entirely, they point out, when their role models are Venus Williams and Mia Hamm.

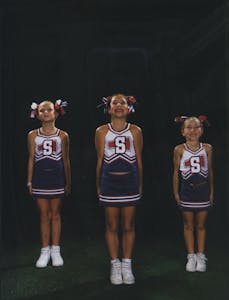

The argument against cheerleading was most forcefully articulated by Sports Illustrated’s Rick Reilly, who devoted a column of his—“Sis! Boom! Bah! Humbug!”—to the subject in 1999. “I guess this is like coming out against fudge and kittens and Abe Lincoln, but it needs to be said,” he warned his readers. “I don’t hate cheerleading just because it’s about as safe as porcupine juggling. I also hate it because it’s dumb. The Velcroed-on smiles. The bizarre arm movements stolen from the Navy signalmen’s handbook. The same cheers done by every troupe in every state. What’s even dumber is that cheerleaders have no more impact on the game than the night janitorial staff. They don’t even face the game. They face the crowd.” But such criticism has not had much resonance in Texas, where cheerleading is bigger than ever. All-star cheerleading—in which squads compete against one another and exist independent of school teams—is currently one of the fastest-growing athletic activities for girls in the nation, with Texas being home to one out of every four all-star squads. More than four hundred cheer gyms have opened from Beaumont to El Paso, each with a more exuberant name than the last: Atomic Cheer, Spirit Explosion, Cheer Factory, Cheer USA, Lonestar Cheer, Planet Cheer, Tumble Town, Wild About Cheer. The industry that Herkie helped to establish more than half a century ago now generates hundreds of millions of dollars a year. So popular has cheerleading become that the Dallas suburb of Garland has 48 squads, 12 of which are for kindergarteners alone.

A half-hour’s drive north of Garland, at Pro Spirit, in McKinney, I watched a peewee squad practice one afternoon. Pro Spirit is housed in a cavernous metal building on the western edge of town, where the subdivisions start to give way to grassland and the effect is that of entering a place set apart from the rest of the world. The walls are covered with shadow boxes filled with ribbons and medals and photos of girls triumphantly hoisting colossal trophies above their heads. On the day I visited in July, several dozen mothers sat in a darkened room that looked out onto the blue mats where their children were learning how to tumble; above them hung a sign that read “Positive Parents. Positive Coaches. Positive Kids. Positive Results.” The glass partition they sat behind was lit in such a way that they could observe their children but their children could not see them. In sparkly outfits that glimmered under the fluorescent lights, the four- and five-year-olds executed near-flawless routines in miniature; one girl was held up in the air (with the assistance of her coach) by four equally tiny bases. Their mothers gave unseen thumbs-up signs and applauded; the girls gazed back at the opaque glass, flashing their practiced hundred-watt smiles. They had a certain girly glamour to them despite the occasional runny nose. Each girl was honing the skills she would need ten years from now, one mother told me, to win a spot on her high school cheerleading squad.

ALTHOUGH REPRESENTATIVE EDWARDS could not name a specific high school cheerleading squad or incident that spurred him to action, he didn’t pull the issue out of thin air, either. The National Cheerleaders Association issued a warning in 1995 that is still given to every squad that attends its annual competition. “Deductions will be given for vulgar or suggestive choreography, which includes but is not limited to movements such as hip thrusting and inappropriate touching, gestures, hand/arm movements and signals, slapping, positioning of body parts and positioning to one another,” it reads. All facets of a performance, it continues, “should be suitable for family viewing and listening.” (Although the wording is broad, it is far more precise than the definition that Edwards gave his colleagues for overly sexually suggestive cheerleading: “Any adult that’s been involved with sex in their lives will know it when they see it.”) The National Cheerleaders Association issued the warning after its judges began noticing a change in tone at competition. Hemlines had crept to the top of the thigh, and uniforms were showing more and more midriff. Of most concern to judges was the music that a few squads had selected to perform to. (Last year a college squad was cautioned that it would be penalized if it presented the routine it had prepared to 50 Cent’s bawdy “Disco Inferno.”) “We are the gatekeepers,” explained the National Cheerleaders Association’s vice president of marketing, Karen Halterman, when I visited the NCA headquarters, in Garland, this summer. “Our entire culture has been desensitized to explicit sexual content. We don’t want to impose or even define morality, but we must have parameters.”

Whether cheerleaders are singing Big & Rich’s “Save a Horse (Ride a Cowboy)” in the locker room or taking up practice time mimicking the dance moves in Ludacris’s “P-Poppin’” video—and what P stands for can’t be printed in this magazine—popular culture has put its imprint on what was once considered just good, clean fun. “If I tell my girls to come up with their own routine and I come back to polish it, my jaw drops when I see what they’ve done,” said coach Billy Smith, of Dallas’ Spirit Celebration. “When I tell them that we’re going to have to change the routine, they’ll say, ‘But this is what Beyoncé is doing!’” And yet contrary to what was argued on the House floor, raunchy performances—at least at the high school level—usually stay off the playing field; coaches know that their squads will be penalized at competition if their routines are off-color, and cheerleading sponsors are not eager to showcase their girls shaking it at games that will be attended by parents and members of the school board. So where are these risqué routines that so inflamed the passions of the Legislature? Over and over again, I heard the same answer from parents and coaches, all of whom were white and asked not to be quoted by name: “It’s a problem at the black high schools.” They read particular significance into the fact that the bill’s author, Representative Edwards, is African American. “Go to an inner-city football game, and you’ll see what I mean,” one coach advised me.

So I went to the first football game of the season at South Oak Cliff High School, in a gritty pocket of Dallas that could not have looked more dissimilar from Wonderbreadland. But at its heart, South Oak Cliff was no different from Rockwall; despite the finger-pointing from the suburbs, there was no bumping and grinding that Friday night, no booty shaking or “dropping it low.” The most offensive move of the evening was one very PG-rated shimmy. The squad had on the most demure cheerleading uniforms I had seen: loose-fitting athletic shorts and matching black tank tops with letters that spelled out “Bears.” Wearing dabs of glittery eye shadow and ponytails secured with white, star-spangled ribbon, the girls beamed up at the crowd as they did herkies along the sidelines. Perhaps there was a cheerleading squad somewhere in Texas that night whose routines would have made our legislators blush, but it was not to be found in South Oak Cliff. Then again, as long as there are cheerleaders, there will always be those who pass judgment on them; they are athletes in short skirts, stranded between the same impossible expectations that all women find themselves caught between. They must be attractive but not too sexy. Fit but not too athletic. Confident but not too outspoken. If the cheerleader is the symbol of perfect womanhood, she will never measure up until we figure out exactly what it is that we want women to be.

None of that mattered on that warm August evening, when the South Oak Cliff cheerleaders called out in unison to the players on the field, “You make the touchdown! We’ll make the noise!” The fans roared back their approval. Little girls studied the cheerleaders, waving miniature pom-poms in the air; lanky boys leaned over the railing, trying to catch their attention. The cheerleaders were beautiful under the stadium lights—young and radiant, with an aura of celebrity to them—and even when their team fumbled and fell behind, they kept on cheering.

Editor’s note: This post has been updated to correct the spelling of a name. It’s Gwenda Swearengin, not Swearingen.

- More About:

- Sports

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Football

- Dallas