This is the second part of a series produced with the Texas Tribune about state senator John Carona, the founder and CEO of Associa, the largest HOA management company in the United States. The first story can be read here.

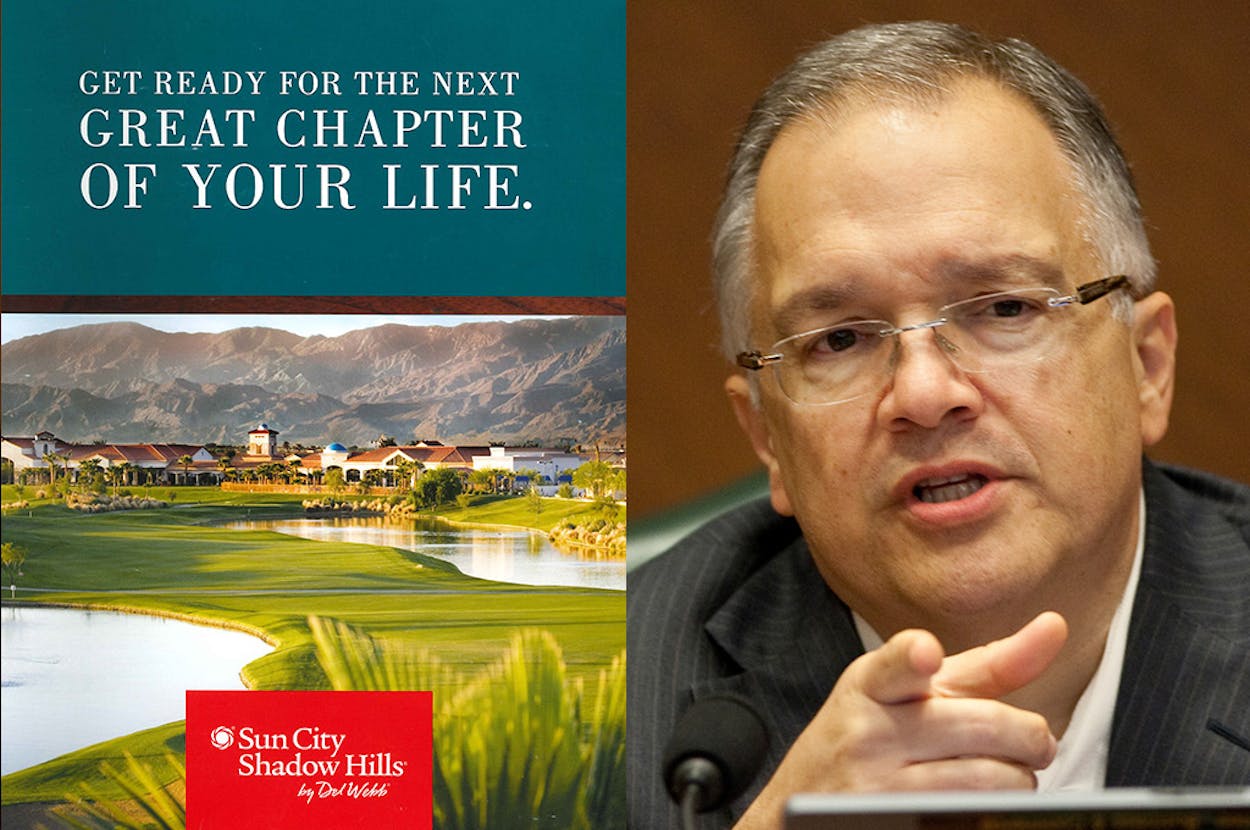

The slick brochure advertising homes in the Sun City Shadow Hills neighborhood near Palm Springs has escapist senior fantasy written all over it.

On the cover, a lush green expanse of golf course fairway cuts through two shimmering lakes and ends at what looks like a Spanish village, where uniform clay roofs sit on top of white building facades, offering a perfect color transition between the Bermuda grass in the foreground and the desert mountain landscape behind it.

But there is trouble beneath the utopic veneer: Many of the 55-and-up “active adults” who live here have become disillusioned with the homeowners association and the property managers who run it. They worry about how their nearly $9 million in annual dues money is being spent, complain about financial conflicts of interest, and say they collectively are getting gouged by fees and fines without the kind of transparency or due process one would expect from a government agency with similar responsibilities.

Like most new developments in U.S. metropolitan areas, Shadow Hills is governed by a private homeowners association, and membership is not optional. To live here, you must become a member, pay $237 a month in dues and abide by a lengthy and sometimes onerous set of rules. One that has been generating controversy of late is the “Conduct Code” section of the sssociation’s rules and regulations. It says homeowners are responsible for the actions of friends, visitors and even vendors.

That was the policy the HOA cited to Carolyn Little when she was issued a $50 speeding ticket, even though it wasn’t her car and she wasn’t driving. It was a Home Depot carpet installer who got caught by the association’s private police force for driving seven miles over the 35 mph speed limit down Sun City Blvd. Little, 71, said she just happened to be the first homeowner expecting a visit from Home Depot that day—and it was her address that the driver gave the guard when he checked in at the front gate.

“They want their money and they don’t care if it’s at the resident’s expense,” she said. “We like it here. It’s just that these rules are crazy.”

The dissidents say complaints about heavy-handed rules fall on deaf ears in Shadow Hills: the association recently authorized the purchase of another radar gun—evidence, as they see it, that the property managers are looking out for their bottom line and not the best interests of the homeowners.

While the Sun City Shadow Hills Community Association was organized as a nonprofit dedicated to the protection of the neighborhood and its residents, it is run by a for-profit management company. With a budget of about $10 million a year, it’s not unlike running a medium-sized business.

In this case the task falls to Professional Community Management, or PCM, a subsidiary of Associa, the largest HOA management company in the United States. The company’s founder and CEO is state Sen. John Carona, R-Dallas, chairman of the powerful Senate Committee on Business and Commerce and architect of Chapter 209 of the Texas Property Code—the section dealing with single-family HOAs.

Associa bought PCM, one of the largest property management firms in Southern California, in 2010, marking a decade of acquisitions by the privately held company. In 2000, Carona listed just five companies in which he reported ownership or executive oversight on financial disclosures Texas elected officials must provide. By 2011, the figure had ballooned to more than 120 companies.

A dizzying number of acquisitions and spinoffs has turned Associa into an HOA management behemoth. The company now operates in 31 states, plus several locations in Canada and Mexico. It also has created numerous subsidiary businesses to cash in on the growing HOA market and to become what Carona calls “a one stop service opportunity” benefitting both his company and his customers.

Carona was not familiar with the specific concerns from Shadow Hills, one of more than 9,000 associations Associa manages, but he said complaints from homeowners generally come from a vocal minority: “In the service business you’re only going to hear from the people with problems,” he said. Associa spokeswoman Carol Piering referred questions about dealings with homeowners to the volunteer board that is legally charged with overseeing the affairs of the estimated 5,400 residents living in Shadow Hills.

“With a community this large, it is not uncommon to have a variety of viewpoints that create a dialogue that would contribute to the board making informed decisions for the common interest of all of the residents,” she said.

Carved from the picturesque Coachella Valley, Shadow Hills offers all the amenities one might expect in an upscale retirement community: two eighteen-hole golf courses, tennis courts, indoor and outdoor pools, a bar, a restaurant and even an amphitheatre. On a recent visit to the massive Montecito clubhouse and recreation center, sixty- and seventy-somethings could be seen playing bridge and mahjong (a card game), lifting weights, loosening up with water aerobics and, in one pulsating room, taking a Zumba dance class.

“Baila! Baila! Sabor!” the music blared.

Only senior citizens are allowed to live in Shadow Hills, so most people came here to retire or to spend their winter months in the warm desert climate. Tangling with the HOA board, generally speaking, wasn’t on the to-do list.

“I don’t think any of us were doing anything more than buying a house and in some cases buying into a lifestyle,” said Martin Stone, 63, a former bankruptcy lawyer who moved here two years ago after a heart attack sidelined his career. “I don’t think any of us thought we were buying shares in a private government and that it was then going to seek to exercise this level of control over our lives.”

The first rumblings of discontent were felt in late 2011 when the Shadows Restaurant was temporarily shut down for a kitchen remodel few knew about. At first the complaints were confined to an inquisitive group of seniors who were easily dismissed by the board as troublemakers with too much time on their hands and too many pesky questions.

Then the board awarded PCM-Associa an additional $3,000-a-month contract, effective January 1, 2012, to manage Shadows Restaurant and revealed plans for a large expansion, even though it had been losing tens of thousands of dollars a month.

Residents say things reached a boiling point in early 2012, after the board held a raucous town hall meeting to discuss plans to expand the money-hemorrhaging restaurant. The board subsequently appointed an Associa subsidiary employee, Jerald Cavoretto, to fill a vacancy on its board of directors, which fueled more criticism about PCM-Associa’s influence over the non-profit board. Cavoretto was later elected to a full two-year term.

Cavoretto, who serves as board treasurer, said in an email that he recuses himself from voting on any issue related to PCM-Associa “or any other issue which I feel would present a conflict.”

For critics, the permissive ethics rule sits atop a pile of complaints about PCM-Associa and the Shadow Hills board, which they say has been too cozy with the management company and unreasonably slow in providing the financial documents to which they believe they are entitled.

Ronald Bob Marley, a CPA for more than fifty years and former president and CEO of Baskin Robbins, said he moved to Shadow Hills to live out his golden years in peace. But after the restaurant controversy exploded, he threw in with the graying revolutionaries.

Marley, 82, said in all of his years in the business world he had “never seen such a one-sided contract” as the one PCM-Associa signed with the association. The company is paid about $145,000 a year in management fees, figures from association financial records indicate. Marley estimates the association is also paying $3 million a year to Associa for payroll, and association records show that includes a processing fee of 5 percent — which is above and beyond the management fee — and a variety of tack-on charges.

Marley and other critics are upset that PCM-Associa is also advancing itself large sums each month, without formal invoices, to cover payroll costs. They liken the payments to a revolving zero-interest loan.

“They’re using our money to finance their business,” Marley said. In emails exchanged with one dissident homeowner, board members defended the payroll advances, saying they are authorized and reconciled monthly to reflect actual costs—which are sometimes higher than the advances.

Shadow Hills is not the only common interest development where homeowners have complained about a lack of transparency and overly warm contractor ties with governing boards. That’s a common refrain across the industry, said Mike Parades, former owner of an HOA management company and instructor of best management practices at the Community Associations Institute, the chief lobby and education group for HOA interests.

While it’s generally a low-profit business, large “mega-management” companies like Associa rack up profits by selling ancillary services to a captive audience, Parades said. He said in many cases the associations often have no idea that their management company has ties to everything from the maintenance contractors to insurance and even banking services.

“They are a big business and they are all run by a volunteer board of directors that may or may not understand what the hell they’re doing,” Parades said. “That’s kind of scary, isn’t it?”

Carona said Associa managers always disclose the company’s links to subsidiaries, presenting itself as a turn-key operation with a long list of affiliated contractors.

“We don’t ever go and represent ourselves as just a management firm. From day one we represent ourselves as a management and lifestyle services firm,” he said. “We show our full array of offerings but clients are always free to pick and choose from what they want and what they don’t want.”

However, Carona also said in mid-March that Associa’s ownership of Dallas-based Associations Insurance Agency Inc. was disclosed on AIAI’s website. It was not. After the Tribune asked about it, the Associa parentage was disclosed under an “About Us” blurb.

Parades said the CAI code of ethics, which he helped draft, requires more than that, though. He says management companies must provide associations with written disclosures of any actual or perceived conflicts of interests, including ownership of any companies providing ancillary services.

According to interviews and published reports, board members repeatedly have said they were unaware of Associa’s links to subsidiaries and affiliates, including AIAI, founded and owned by Associa.

Linda Jeter, president of the board of the Silvermill Homeowners Association in Katy from 2008 to 2010, said she and fellow members did not know that Associa affiliates had quietly gotten in the banking and insurance business, for example.

“They did switch our accounts over to the Associa bank and the Associa insurance without ever saying anything about it,” she said. “We didn’t really pay any attention to it.”

The board fired Associa after complaining of poor service and unresponsiveness, but it had nothing to do with directing any business toward affiliated vendors, she said.

(Carona was the co-founder and largest shareholder of Dallas-based First Associations Bank, which specialized in HOA accounts; the bank was sold earlier this year to California-based Pacific Premier Bancorp, Inc., which made Carona a director and retained its depository services agreement with Associa, according to Securities and Exchange Commission disclosures).

Gary Stone, a former Associa subsidiary manager in Dallas, says it’s no coincidence boards often have no idea that an Associa-owned company is producing the insurance policy that an association is required to have.

When it came to discussing the sale of AIAI coverage to HOA boards, his managers were expected not to mention the ownership and to “just tell ‘em they’re good policies,” Stone said.

“I would have to go the board and say, ‘Look, now it’s insurance time,’ and ‘Oh look, we’ve got a new insurance company that we can use,’” Stone said. “It just happened to be Carona’s.”

Carona told the Tribune that there probably are times when “we push a little hard” to sell add-on products but he said the company’s policy is to disclose ownership ties and he insisted the bundled services are “good for the client.”

“Nothing that we’ve ever proposed that I’m aware of in terms of ancillary services has ever been any higher than the market rate,” he said.

(Whether the insurance policies are a bargain or not is a subject of dispute. Carona says AIAI never intends to sell insurance to assocations unless it’s the lowest bidder. But critics say Associa stacks the bidding process in its favor and sells questionable “master program” policies that don’t provide adequate coverage of risk).

The laws impacting association-ruled communities vary from state to state. But people who live in them willingly sign contracts binding them to some pre-determined conformity. Those who break the rules or quit paying their dues—the private contractual version of a property tax—face penalties or even foreclosure, because otherwise their neighbors would have to endure their nuisances or pay their share of the assessment load.

With almost a fifth of the U.S. population living in HOA-governed communities, “you’re going to have problems,” said CAI spokesman Frank Rathbun. But he said polls commissioned by the CAI routinely show 70 percent or more of the people who live in them are happy with their HOAs.

“What politician wouldn’t love that kind of approval rating?” Rathbun asked.

The problem is that when things go south, like it has for many of the residents of Shadow Hills, generally the only options are to sue, a costly and uncertain venture, or to eject the board in an election—which can be harder than it sounds. In Shadow Hills and other HOA-ruled communities, developers control the votes of unoccupied houses, so until a subdivision is fully occupied they retain major influence over board seats.

And unlike a typical town square, the common areas of Shadow Hills are private property, so the normal tools of democracy aren’t always readily available to those who want to change the system. When a group of dissatisfied residents asked for the board’s permission to form a club and use a conference room in the clubhouse in which to gather and discuss their concerns, for example, they were turned down on the grounds that a similar group already existed. The management company also controls the website and the monthly magazine, The View, whose pages read as if no one has ever complained about anything at Shadow Hills. Even planting yard signs or distributing flyers in residents’ mailboxes must meet approval of the association, the dissidents say.

Martin Stone, the former bankruptcy lawyer and Shadow Hills rabble rouser (no relation to Gary Stone of Dallas), recently had his rights to the common areas suspended after the association said his swamp cooler violated strict architectural design protocols. He claims they even deactivated the transponder on his car—so he can’t automatically open the front gate of the neighborhood from his car when he comes and goes.

Living under the current board rules “has all the evils of a monarchy with none of the benefits of noblesse oblige,” Stone fumed.

The dissidents discussed filing a lawsuit against the HOA but say they don’t want to go that route. Instead, they are throwing their energy into the upcoming 2014 spring board elections—the first in which residents expect there will be no developer-backed candidates. Stone and other critics, including former Deloitte accountant Gaelyn Lakin, say the rebellion has morphed into a full-fledged opposition movement, and they believe they have a good shot at electing neighborhood leaders who will better represent their interests, throw open the books and strike a better management deal than the one they say never should have been given to PCM-Associa.

That day can’t come soon enough for Lakin.

“I’m ready to move back to the United States,” she said.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- John Carona