As the wife of the president of the United States, Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Johnson was renowned for her graciousness, dignity, and poise in the national limelight, for her charm and effectiveness as a political speaker, and for the capabilities she displayed in her role as First Lady, as a public figure of the first magnitude. When she was young, however, few who knew her would have dreamed that she possessed such qualities.

As a girl, a young woman, and a young wife, in fact, Lady Bird (she was given her nickname by a nurse because “she’s purty as a ladybird”) was not a person to whom other people paid much attention. During her childhood—in the East Texas town of Karnack—the reason was her manner. The lonely little girl, whose mother died when she was five and whose older brothers were off at school for much of the year, lived alone with her father, Thomas Jefferson Taylor, a tall, burly, ham-handed owner of a general store and cotton gin, loud and coarse, who “never talked about anything but making money” and was known as “Mr. Boss” throughout Harrison County. While apparently fond of his daughter, he didn’t know what to do with her and packed her off alone at the age of six, a tag around her neck for identification, to her mother’s spinster sister in Alabama. Lady Bird was raised by her aunt, who moved to Karnack. Frail, sickly Aunt Effie “opened my spirit to beauty,” Lady Bird says, “but she neglected to give me any insight into the practical matters a girl should know about, such as how to dress or choose one’s friends or learning to dance.”

Lady Bird loved to read, particularly in a beautifully bound set of books that had belonged to her mother. She memorized poems that she could recite decades later, finished Ben-Hur at the age of eight. As for other companionship, the handful of students at Karnack’s one-room school were almost all children of the itinerant black sharecroppers who worked her father’s 18,000 acres of red clay cotton land; they seldom stayed for long, since her father was notoriously ruthless in his treatment of tenants behind in their rent. “I came from…a small town, except that I was never part of the town—lived outside,” she says. During her high school years in nearby Marshall (she graduated at fifteen), the lonely little girl became a lonely young woman. Despite her expressive eyes and smooth complexion, she was considered plain, and her baggy, drab clothes seemed almost deliberately chosen to make her less attractive. To the other girls, preoccupied with dresses and dancing and boys, she seems to have been almost an object of ridicule. Says one: “Bird wasn’t accepted into our clique….She didn’t date at all. To get her to go to the graduation banquet, my fiancé took Bird as his date and I went with another boy. She didn’t like to be called Lady Bird, so we’d call her Bird to get her little temper going….When she’d get in a crowd, she’d clam up.” In talking about her, they recall a shyness so profound that it seems to have been an active fear of meeting or talking to people. Lady Bird’s own recollections are perhaps the most poignant. “I don’t recommend that to anyone, getting through high school that young. I was still in socks when all the other girls were wearing stockings. And shy—I used to hope that no one would speak to me.” She loved nature, boating on the winding bayous of Lake Caddo or walking along its shores (“drifts of magnolia all through the woods in the Spring—and the daffodils in the yard. When the first one bloomed, I’d have a little ceremony, all by myself, and name it the queen”), but the boating and walking were also usually “by myself.” So deep was her shyness that, as a high school senior, she prayed that if she finished first or second in her class, she would get smallpox so that she wouldn’t have to be valedictorian or salutatorian and have to make a speech at graduation. (She finished third.) The school newspaper joked that her ambition was to be an old maid.

Although she remained silent and retiring at the University of Texas, indications of determination and ambition began to appear. Instead of returning to Karnack when she graduated in 1933, as her father and aunt had anticipated, she insisted on spending an extra year at the university, so that she could obtain a second degree—in journalism, “because I thought that people in the press went more places and met more interesting people, and had more exciting things happen to them.” Attempting to overcome her shyness, she became a reporter for the Daily Texan and forced herself to ask questions at press conferences. Nevertheless, the attempt seemed to be a losing one. Except at press conferences, one friend recalls, “she was always pleasant, smiling, and so quiet she never seemed to speak at all.” Her best friend, Eugenia Boehringer, despaired of making her more outgoing or even of persuading her to change her style of dressing; despite the “unlimited” charge account her father had opened for her at Neiman-Marcus, she still wore flat-heeled, sensible shoes and plain dresses, of colors so drab that they seemed deliberately chosen to avoid calling attention to herself. And despite her journalism degree, when college ended, she did return to Karnack. It was on a visit to Austin some months later, in September 1934, that by chance, in the office in which Eugenia Boehringer was working as a secretary, she met Lyndon Johnson, who was then assistant to Congressman Richard M. Kleberg. Eugenia and Johnson were friends; through her, he already knew who Lady Bird was; he immediately asked her for a date and on that first date he asked her to marry him, which she did in November.

After her marriage, there was an additional reason that people did not pay much attention to Lady Bird Johnson: the way her husband treated her.

Upon their return to Washington from their honeymoon, he told her that he wanted her to serve him his morning coffee in bed; to bring him his newspaper in bed, so that he could read it as he sipped his coffee; to lay out his clothes; to fill his fountain pen and put it in the proper pocket; to fill his cigarette lighter and put it in the proper pocket; to put his handkerchief and money in the proper pocket. And to shine his shoes. And she performed these chores. (When he first told her he wanted his coffee in bed every morning, she was to recall, “I thought, What!?!? Me?!?! But I soon realized that it’s less trouble serving someone that way than by setting the table and all.”) And he made sure that everyone knew that she was performing these chores, loudly reminding her about her duties in front of other people. He was constantly inviting congressmen, fellow staffers, and friends to their modest one-bedroom apartment on Kalorama Road at the last minute and telephoning Bird to inform her that another two guests—or ten—would be arriving shortly for dinner. And in these telephone calls, he did not ask her if she could handle the additional people, he simply told her—curtly—that they were coming. Often the invitees would be in the room with him when he telephoned. They heard his tone of voice.

The trip back and forth to his district, a trip that had to be made at least once, and usually more than once, each year, was a difficult one, since the 1,600 miles of roads between Washington and Austin were not the broad interstate highways of later decades; although Lady Bird was to recall that the distance could be covered in “three hard days,” generally the trip took five days. After he was married, Lyndon Johnson no longer took that trip. One way in which Herman Brown repaid Johnson for the federal contracts he procured for Brown and Root was to place the company plane at the Johnsons’ disposal. But only one Johnson used the plane. Lyndon Johnson flew back and forth. His wife drove—drove, after she had packed. Lady Bird disliked flying, but the principal reason she made the long drive instead of using the Brown and Root plane was that the Johnsons did not feel they could afford two sets of household furnishings or a second car. Every time Lady Bird drove from Washington to Texas and back, she took with her a carful of boxes. “For years,” she would later recall, “my idea of being rich was having enough linens and pots and pans to have a set in each place, and not have to lug them back and forth.” And of course everyone in the Texas delegation was aware of this disparity in the Johnsons’ travel arrangements. Says one congressman: “He treated her like the hired help.”

Lyndon Johnson possessed not only a lash for a tongue but a talent—a rare gift, in fact—for aiming the lash, for finding a person’s most sensitive point, and striking it, over and over again, without mercy. And he did not spare the lash even when the target was his wife—not that great talent was required to discern the rawest of Lady Bird’s wounds: her terrible shyness, her dread of having attention called to herself.

Everyone was aware of the way he talked to her because he talked to her that way in public, shouting orders at her across a crowded room at a Texas State Society dinner (“Lady Bird, go get me another piece of pie.” “I will, in just a minute, Lyndon.” “Get me another piece of pie!”). “He’d embarrass her in public,” recalls Wingate Lucas, a congressman from Fort Worth. “Just yell at her across the room, tell her to do something. All the people from Texas felt very sorry for Lady Bird.” If while entertaining friends at home or while staying overnight at a friend’s house, he saw some imperfection in her attire, such as a run in her stocking, he would order her to change stockings, “just ordered her to—right in front of us,” as her friend Mary Elliot recalls.

Also public were Lyndon’s constant attempts to get Lady Bird to improve her appearance, about which she had always been so sensitive—to make her lose weight, to wear brighter dresses, to replace the comfortable low-heeled shoes she preferred with spike-heeled pumps, to get her hair done more often, to wear more lipstick and more makeup. And after 1940, when his assistant John Connally married Idanell Brill, Johnson was able to flick the lash even harder. The dazzling Nellie Connally was everything Lady Bird was not—perfectly dressed, outgoing, poised, charming, beautiful; as a freshman at the University of Texas, she had been named a Bluebonnet Belle, one of the ten most beautiful girls on the campus; as a junior, she was named the most beautiful: Sweetheart of the University. After Nellie became a member of the Johnson entourage, Lyndon made sure that Lady Bird never forgot the contrast now so conveniently near at hand. “That’s a pretty dress, Nellie. Why can’t you ever wear a dress like that, Bird? You look so muley, Bird. Why can’t you look more like Nellie?” Nellie, who had become close friends with Lady Bird, was distressed at such remarks. “He would say things like that right in front of whoever was present. ‘Get out of those funny-looking shoes, Bird. Why can’t you wear shoes like Nellie?’ Right in front of us all! Now, can you think of anything more cruel?” Aware of Lady Bird’s shyness, her almost visible terror at having attention called to herself, acquaintances said to each other: “I don’t know how she stands it.” And, of course, because of the complete lack of respect with which she was treated by her husband, they didn’t have much respect for her, either. Seeing that in her relationship with Lyndon her opinion didn’t count, they gave it little consideration themselves. She talked hardly at all, and when she did try to talk, Nellie says, “nobody paid any attention to her.”

Not long after he was elected to Congress in 1937, moreover, Johnson had begun spending frequent weekends at Longlea, an eight-hundred-acre estate in the northern Virginia hunt country that had been built by Charles E. Marsh, the immensely wealthy publisher of the Austin American-Statesman, and designed by Marsh’s mistress, Alice Glass. Glass, a shade under six feet tall, with creamy skin and long reddish-blond hair, a woman so spectacular that the noted New York society photographer Arnold Genthe called her “the most beautiful woman I have ever seen,” was a small-town girl from Marlin, Texas, who had become a witty, elegant hostess of a brilliant table and a sparkling salon of politicians and intellectuals. In addition, she possessed a political acumen so keen that the toughest Texas politicians enjoyed talking politics with her; it was Alice Glass who devised a compromise that pulled Johnson and the fierce Herman Brown off a collision course that had threatened Johnson’s career. By 1940 Alice Glass had been Lyndon Johnson’s mistress for more than two years, in a passionate love affair of which Marsh, patronizing and paternalistic toward the young congressman, was unaware. Observing Johnson’s willingness to sit silently listening to Alice read poetry, knowing the risks he took in being the lover of the consort of a man so vital to his political career—this affair stands out in his life as one of the very few episodes in it that ran counter to his ambitions—the Longlea circle believed that his feelings for Alice were unique, a belief shared by Alice, who had told intimates that she and Johnson had discussed marriage. In that era, a divorced man would be effectively barred from public office, but she said that Lyndon had promised to get divorced anyway and accept one of the several job offers he had received to become a corporate lobbyist in Washington. As a result, she kept fending off marriage proposals from Marsh. “She wouldn’t marry Marsh after she met Lyndon,” her sister, Mary Louise, says.

Whether or not Lady Bird was aware of her husband’s affair with Alice—and the circle of Longlea “regulars” was certain she was—weekends at the Virginia estate must have been especially difficult for the young wife; to Alice’s adoring sister, Mary Louise, and to Alice’s best friend, Alice Hopkins, both of whom knew of the affair, she was an obstacle to Alice’s happiness, and of course, she was not at home in the brilliant Longlea salon. No matter how many times he met her, Charles Marsh had trouble remembering her name; he was constantly referring to her as “Lyndon’s wife.” “Everybody was trying to be nice to her, but she was just…out of place,” Alice Hopkins says, and although the first part of that sentence may not have been true, the second was—and Lady Bird knew it; decades later, describing Longlea in an interview with me, she said: “My eyes were just out on stems. They would have interesting people from the world of art and literature and politics. It was the closest I ever came to a salon in my life….There was a dinner table with ever so much crystal and silver.” She appears to have felt keenly the contrast between herself and her hostess: “She was very tall, and elegant, really beautiful….I remember Alice in a series of long and elegant dresses and me in—well, much less elegant.”

On many weekends, moreover, Lady Bird was not at Longlea. “I could never understand how she stood it,” Mary Louise says. “Lyndon would leave her on weekends, weekend after weekend, just leave her at home.”

Throughout Lady Bird Johnson’s life, however, there had been hints that behind the terrible shyness, there was something more—much more.

At the university, there had been her decision to get a journalism degree and the courage with which she forced herself to ask questions at press conferences—and the glimpses her few beaux had beneath the quietness. One of them, Thomas C. Soloman, recalls that for a time “I thought I was the leader.” But, he says, he came to realized that “we had been doing what she wanted to do. Even when we went on a picnic, it was she who thought up the idea….I also knew she would not marry a man who did not have the potentiality of becoming somebody.” J. H. Benefield came to realize that the shy young woman “was one of the most determined persons I met in my life, one of the most ambitious and able.”

Handed the task, customary for congressmen’s wives, of escorting constituents visiting Washington, she carried out the assignment with unusual thoroughness, not only arranging the standard 8:30 a.m. tours of the Capitol but taking the visitors farther afield: to Mount Vernon and even Monticello. Realizing that her husband, despite his prenuptial avowals of fervent interest in culture and history, would never visit the Smithsonian Institution or the Civil War battlefields, she made these tours with his constituents instead. And after a while, when a visitor had a question about a building they were visiting, the answer would be readily available. A friend came to see that “she must have read everything about the city of Washington and its history, and the Capitol, and Mount Vernon and Monticello; I don’t mean just guidebooks but biographies of Jefferson and Washington. She knew everything—and I mean everything—about the gardens at Monticello and how Jefferson had planned them. She even knew about the Civil War battlefields. She had done a tremendous about of work, without telling anyone.” Asked a question, she would reply in a voice so soft as to be almost inaudible. “She would never say one word unless you asked,” one Texan says, “but if you asked, she always knew the answer.” Not only did she grant, eagerly, graciously, any favors that the visitors requested, she suggested other favors—hotel reservations, train schedules for a side trip to New York. “I early learned,” she says today, that CONSTITUENTS was spelled with capital letters,” and she didn’t forget their requests. Her husband had told her to get a stenographer’s notebook and carry it in her purse everywhere, jotting down anything she had to do. She never forgot the notebook; it—and her diligence in crossing off the items written in it—would be remarked upon by her friends for the next forty years.

Even at Longlea, there were hints—although the scintillating Longlea regulars didn’t notice them. She seemed always to be reading. One summer was to become enshrined in Longlea lore as “the summer that Lady Bird read War and Peace”; the regulars snickered because the quiet little woman carried the big book with her everywhere—even though, by the end of summer, she had finished it. When, during the loud arguments to which she sat silently listening, a book would be cited, Lady Bird would, on her return to Washington, check it out of the public library. One was Mein Kampf, which Charles Marsh had read and to which he was continually referring. She read it, and while she never talked about the book at Longlea, when Hitler’s theories were discussed thereafter, she was aware that, while Marsh knew what he was talking about, no one else in the room did—except her.

And there were other qualities, which were noticed even though their significance was not. To the regulars’ condescension, Lady Bird Johnson responded with an unshakable graciousness. While Alice Hopkins says that Lady Bird “was just out of place,” Mrs. Hopkins adds that “if everyone was just trying to be nice to her,” she would be nice right back, calm and gracious—“self-contained.” Even Alice Glass’ sister has to admit that there was something “quite remarkable in her self-discipline—the things she made herself do. She was forever working,” not only on her reading but on her figure—she had always been “dumpy,” but in 1940 or 1941 the extra weight came off, and stayed off.

And as for her husband’s affair with the salon’s mistress, “oh, of course,” Lady Bird must have known, the regulars say. Wasn’t her husband often going—without her—to Longlea when, as she could easily have determined, Charles Marsh was not at home? But although Mary Louise says, “I could never understand how she stood it,” stand it she did. “We were all together a lot—Lyndon and Lady Bird and Charles and Alice,” Mary Louise says. “And Lady Bird never said a word. She showed nothing, nothing at all.”

When, at Texas State Society parties or other Washington social functions, her husband bellowed orders at her across the room, or insulted her, she never showed anything, either. She would sit silently or say simply, “Yes, Lyndon,” or “I’ll be glad to, Lyndon,” and she would do so as calmly as if the request had been polite and reasonable. People might say to one another, “I don’t know how she stands it,” but she stood it—and she stood it with a dignity that his shouts and sarcasms could not rattle, a dignity that was rather remarkable. But most acquaintances didn’t really notice this. Their attitude toward Lady Bird Johnson was influenced by her husband’s attitude toward her. She never tried to talk very much, of course, and when she did, she wasn’t listened to very much. She was just a drab little woman whom nobody noticed.

As for politics, apart from entertaining her husband’s guests and his constituents, she had no connection at all with this major activity of his life.

During her husband’s campaign for Congress in 1937—he would be unopposed in 1938 and 1940—she had, as always, a welcoming smile and a warm meal for him and his aides at all hours of the night. But when, occasionally, someone—someone who didn’t know her well—raised the possibility that she herself might campaign, the very suggestion that she might have to face an audience and speak brought such panic to her face that the suggestion was always quickly dropped. Sometimes she could not avoid standing in a receiving line at a reception for the congressman—and although she would shake hands and chat with strangers filing by, she would perform this chore with so obvious an effort that her friends felt sorry for her as they watched; the bright smile on her face would be as rigid as if it had been set in stone.

In 1941 Johnson unsuccessfully ran for the Senate. That campaign was little different. She learned of her husband’s decision to run only after the decision had been made; he didn’t bother to tell her until after the press conference at which he told the public. Then he flew down to Texas to begin the campaign; Mrs. Johnson followed by car, so unessential was her participation considered. Having purchased a movie camera, she took pictures of Lyndon as he gave speeches, but they were for showing at home, not for use in the campaign. “I went around with my little camera, cranking,” she was to say during one of our interviews many years later. As she said this, she held up an imaginary camera in an amateurish way and pantomimed turning the crank, and as she did so, she hunched over a little, portraying—vividly—a timid little woman hanging back at the edge of a crowd, pointing a camera at her husband. Whatever she looked like to others, that was what Lady Bird Johnson looked like to herself. Did she have any other role in the campaign? “I packed suitcases and got clothes washed, and tried to see that Lyndon always had clothes; every day Lyndon went through three or four or five shirts….Traveling with him,…trying to get him to eat a regular meal, or taking his messages. Just being on hand in his hotel to answer the phone so he can take a shower. And sitting on the platform at all the big rallies.” And the few words she had to say on the rare—very rare—occasions when she represented her husband at a minor event (“Thank you very much for inviting me to this barbecue. Lyndon is very sorry he couldn’t be here”) were such an ordeal that they made her friends cringe.

Her single attempt to contribute something more ended in embarrassment. She had been making big pitchers of lemonade and baking batches of cookies and lugging them to the campaign volunteers working in various offices around Austin, and she decided that on these visits, in order to thank the volunteers for their efforts and to spur them on to more, “I would give this little speech to them: ‘Every single vote counts.’” She wrote and rewrote the few paragraphs of that brief talk, memorized it and nerved herself up to give it. But she evidently repeated it too many times. Meeting her on the street one day, a friend smilingly began to quote her speech back to her, and since the friend was not a campaign worker, Lady Bird felt that her speech had become a joke quoted around Austin. That was the end of her speechmaking in that campaign. Forty years later, she was to tell me that when the friend quoted her speech back to her, she realized, “Maybe it had made the rounds. I guess I gave the speech too often.” Hearing a change in her voice as she spoke, I glanced up from my notepad. Mrs. Johnson was at that time 68 years old. Her face was lowered, and she was blushing—a definite, dark red blush—at the memory of that humiliation so many years earlier.

As for the less public side of the campaign—the planning of strategy and tactics—the planners say that the candidate’s wife was almost never present. “Well,” she says, “I elected to be out a lot.” Asked why, she replies: “I wasn’t confident in that field.” Was there also another reason? “I didn’t want to be a party to absolutely everything,” Lady Bird Johnson says.

Back in Washington after the 1941 campaign, she had a new apartment in the Woodley Park Towers off Connecticut Avenue, much more spacious than the Kalorama Road apartment and with a living room that, she recalls, “just hung over Rock Creek Park, and was just filled with green.” But an apartment wasn’t what she wanted. “I had been yearning and talking about having a home,” she recalls. The Johnsons had been spending about six months of the year in Austin, and every year they seemed to be living in a different apartment there—small and temporary. And in Washington, more and more of their friends were buying homes. “The central theme of my heart’s desire was a house,” she recalls, but there was no money to buy one. She and Lyndon had wanted children, but after seven years of marriage there were no children. “This was a sadness,” she remembers, and changes the subject. But sometimes, despite herself, her sorrow slipped out; an old friend was to remember chatting with Lady Bird at this time about other topics; every so often Lady Bird would pause, and a wistful look would cross her face, and she would say, “If I had a son…” or “If I had a daughter…” During the fall of 1941, she was still taking constituents to Mount Vernon—she was to say she stopped counting after her 200th trip—and she was very tired of those trips. Nellie Connally says, “She was like a sight-seeing bus. That’s what congressional wives did: They hauled the constituents around.” During that fall, she still entertained constituents at dinners—dinners at which her guests paid little attention to her. Anxious for something else to do, she enrolled, with Nellie, in a business school in Arlington, taking courses in shorthand and typing; years later, Mrs. Johnson, almost always careful not to say a derogatory word about anything, would say of the business school: “That was a dull, drab little place.” And all during that fall the Texas parties continued at which her husband ridiculed her or shouted orders at her. “The women liked her,” Nellie Connally says. “Every woman sympathized with her. If they didn’t like her for herself—and they did—they liked her because they saw what she had to put up with. It made what they had to put up with not so bad.”

Then came Pearl Harbor. Although Lyndon Johnson had promised Texas voters that if war began he would immediately enlist and be “in the trenches, in the mud and blood with your boys,” he would in fact spend the first five months of the war on the West Coast. When he was about to leave on his first trip to the coast, on which he would be accompanied by John Connally and Willard Deason, he said that Lady Bird might as well get some use out of her typing classes and took her along to type his letters. Telephoning his congressional office every evening, he was told about problems in the district: about federal installations for which he had obtained preliminary approval before his departure—a big Air Force base for Austin, an Army camp in Bastrop County, a new rural electrification line—but that were now stalled in the federal bureaucracy; about scores of businessmen whose plans for construction or expansion of factories were stalled by lack of necessary approvals from federal agencies such as the new War Production board and the Office of Strategic Materials; about letters and telephone calls—hundreds of letters and telephone calls—from constituents about routine pre-war matters and about new war-related problems. There was no one to handle these problems. In Connally, Walter Jenkins, and the brilliant speechwriter Herbert Henderson, Johnson had possessed an exceptional staff, but Jenkins had enlisted in September, Henderson had suddenly, unexpectedly died in October, and Connally’s departure left no one in Suite 1320 of the House Office Building except apple-cheeked Mary Rather—charming, efficient, but only a secretary—and O. J. Weber, bright and aggressive, but only 21 years old and with just a few months’ experience. And the problems had to be handled quickly. If final authorization for the new military bases in the 10th Congressional District was not pushed through, some other congressman would snap up the bases for his district. If constituents didn’t get the necessary assistance in Washington, the feeling would spread that there was no one in the district’s congressional office except secretaries, that the district was without adequate representation in Washington—at a time when a congressman was needed with particular urgency. If Johnson’s absence from Washington was to be prolonged, voters might begin asking why he didn’t resign his seat and let the district elect a new congressman. The political danger was real—and imminent. Let dissatisfaction mount and, with an election scheduled for July 25, 1942, he might, if he didn’t resign, be replaced. Someone had to take over the office, to be in effect, in all but name, the congressman from the 10th District until the real congressman returned. Someone had to handle a congressman’s multifaceted chores: to persuade Cabinet officers and high-level bureaucrats to cut through red tape and get the big projects moving again, to negotiate with the new wartime agencies on behalf of businessmen, to serve as the necessary link between constituents and federal agencies. Discussing the situation out on the coast, Johnson, Connally, and Deason agreed that choosing an ambitious young politician or lawyer from Austin, who might become a possible rival, was too risky. Moreover, the choice had to be someone who was not only totally loyal but who would provide a sense of continuity, someone who would make the district feel that the office was being run as if Lyndon Johnson were still there running it; someone, therefore, who was identified with Lyndon Johnson. It is unclear which of the men first suggested that the best choice—perhaps the only choice—was Mrs. Lyndon Johnson; she thinks it was Deason whom, to her astonishment, she first heard mention her name. Her husband at first dismissed the idea, but the more it was discussed, the clearer it became that it was the only solution. Johnson and his entourage returned to Washington after only two weeks, but learned that he and Connally would soon be leaving again, on a trip whose duration was indefinite. He told Lady Bird she would have to do the job. And when, on January 29, 1942, he and Connally left for the coast again, Lady Bird went to Suite 1320.

On this trip, Johnson and Connally would be gone for ten weeks. The two tall, handsome young Texans traveled up and down the West Cost, visiting shipyards, meeting with Navy training officers and contractors’ representatives to discuss new training programs, going to filmings and Hollywood parties, and having what Connally describes as “a lot of fun” while Johnson was lobbying for a powerful wartime position in Washington. (Connally was only temporarily deferring to Johnson’s wishes in accompanying him. Later, he would push for active service, and would serve with distinction on the aircraft carrier Essex.) The alacrity with which Johnson had leapt into the 1941 Senate race had made Alice Glass realize that her lover’s political ambitions would always take priority and that divorce was not a realistic hope. After the 1941 campaign, she had finally agreed to marry Charles Marsh, but now, when Johnson asked her to visit him in California, she went. An idealist herself who had first been attracted to Johnson because she felt he was an idealist, she still believed in his idealism and felt he was a young man on his way to fight a war or at least to participate in the war effort. (She would become disillusioned by the contract between Johnson’s activities and the grim battles on Bataan peninsula in the Philippines and a great naval battle raging in the Macassar Strait being reported daily in the newspapers, however. Years later, jokingly suggesting in a letter to a mutual friend, Brown and Root lobbyist Frank C. “Posh” Oltorf, that they collaborate on a book on Johnson, she said, “I can write a very illuminating chapter on his military career in Los Angeles, with photographs, letters from voice teachers, and photographers who tried to teach him which was the best side of his face.”) Despite the reality of his West Cost activities, however, Johnson had managed to leave the impression with his wife and staff that active service in a combat zone was imminent, and Lady Bird believed this. And she ran his office.

Her husband didn’t make it easy for her. He did not, in fact, give her much of a vote of confidence before the staff; he appears to have been unable to bring himself to tell Miss Rather and Weber that she was to be in charge of the office. He told her to write him daily letters listing the project she was working on and to leave wide margins so that he could put instructions next to each item, but he told Weber and Miss Rather to write letters, too, and left the impression with them that he wanted them to report to him on how Lady Bird was doing.

At first, she didn’t behave as though she was in charge. Confidence was a scarce commodity for Lady Bird Johnson. Asked years later about her early days in the office, she replies: “I was determined, and I wanted to learn. And I was scared.” She went on attending business school in the mornings, and in the office she downplayed her role, to make it appear to the two secretaries that she was on a level with them: Although she sat at her husband’s desk as he had instructed her to do, she moved a typing table and a typewriter in beside his chair and began to share the typing with the two secretaries—who at first treated her as a sort of apprentice secretary; there is a faintly patronizing note to Weber’s report, in a letter he wrote to Johnson a week after she began working, that “Lady Bird is very industrious about her shorthand and typing at school.” She let Mary Rather, who had experience doing it, make most of the calls to the departments and agencies.

But that changed.

Things weren’t being done the way Lyndon would have wanted, she felt. She was signing all the letters from the office, and, reading them, she was finding misspellings. When she asked Mary and O.J. to correct them, they would correct them in handwriting, and the letters looked, she felt, rather sloppy. Lyndon had never let letters go out like that: One mistake, no matter how minor, and the whole letter had to be retyped, no matter how many times it had been retyped before. And she could not blind herself to the fact that insufficient progress was being made on the projects Lyndon would normally be pushing through the bureaucracy, and that complaints were already beginning to be heard from constituents; Weber himself was to report that “some people were already hollering that Lyndon Johnson had gone off the job and his work wasn’t being taken care of.” She knew how important the efficient operation of his office was for Lyndon. And for her, too. Both of their lives were wholly bound up in his career. In her mind, moreover, he was at war—at any moment he might be facing the enemy. He should he spared worries about the office. That was the least she could do for him.

She knew, for she had heard their complaints over the years, how bitterly Lyndon’s various secretaries resented being made to retype letters over and over again for minor mistakes. It was very hard for her to insist that Weber and Miss Rather retype letters over and over again. But she felt that it was necessary that she do so. And she did. Once, after she had handed a number of letters back to Weber for what she recalls as “small misspellings,” she emerged unexpectedly from her office to find him smacking his fist on his desk in anger. But when he submitted another letter with a mistake, she handed it back to him.

She did things much more difficult—for there were people in Washington more formidable than Weber and Miss Rather.

“There was no doubt about it: O.J. and Mary knew more than I ever would,” she recalls, “but I did have one advantage. I had Lyndon’s name, and he had a network of friends in the departments… and I could get my foot in the door when sometimes a secretary couldn’t. I had a complete picture of my complete lack of experience,” she adds, “but I also had a feeling that nobody cares quite as much as you do about your business, and next to you, your wife… They knew more, but perhaps I cared a bit more.” She told O.J. and Mary that she would not be doing any more typing; form now on, she said, she would sign the letters they typed and handle as many of the calls from the constituents as possible—and she would be dealing with the departments and agencies herself. And, she said, she would be getting in earlier in the mornings; she wouldn’t be going to business school any longer.

Dealing with the departments and agencies. Lyndon’s many allies in Washington, such as the influential Washington insiders Thomas G. “Tommy-the-Cork” Corcoran and James H. Rowe, Jr., could make sure that agency heads and other high administrative officials accepted her telephone calls and, if a visit in person was necessary, could get her in to see them. But Corcoran and Rowe couldn’t help her once she was in. For the previous 29 years of her life, Lady Bird Johnson had never been able to make people listen to her, much less persuade them to do things for her.

She had to make them listen now.

Sometimes, when Lady Bird had an important call to make, Mary Rather, glancing into her office, would see her sitting at her husband’s big desk, in her husband’s big chair, “looking as if she would rather have done anything in the world rather than pick up that phone and dial.”

But she always picked it up.

And if a phone call wasn’t enough, if she had to go to see an official in person, she went to see him—even if the official was a Cabinet officer, even if the official was the most feared of Cabinet officers, Harold Ickes, Secretary of Interior, the tart-tongued, terrible-tempered Old Curmudgeon himself. “There were some real scary moments,” Lady Bird Johnson would recall forty years later. “One time I had to go see that formidable man, Mr. Ickes.” At parties, she had dreaded exchanging even a few words of social chatter with him; now she had to ask him to revoke an order relocating a Civilian Conservation Corps camp and to explain why, for political reasons, it should be revoked. But Ickes’ secretary didn’t keep her waiting too long under the giant moose head that hung over visitors in his anteroom at the Department of the Interior, and when she was ushered in, “he really couldn’t have been nicer.” Peering at her over the top of his rimless spectacles, he listened to her story, and then said simply that he would look into the matter. But hardly had she returned to the office when there was a telephone call from one of Ickes’ assistants. The matter had been worked out as Mrs. Johnson had requested, the assistant said.

During the ten weeks he and Connally were touring the West Coast, Johnson would sometimes telephone, and there was a constant stream of mail—her letters returned with Lyndon’s orders in the wide margins, and letters he wrote with more detailed instructions—and the instructions at first were those that would be given to a political novice. At one point, he even complained to Weber about his wife: “Since she doesn’t get pay she is irregular in writing, and I can’t fire her—Can’t you and Mary help me by persuasive reminders to write daily.” Only a few paragraphs from his letters are known—Mrs. Johnson has not released the rest—but from this handful, the tone appears to have changed. When, as he had been leaving for the coast, he had told her to write personal notes to key supporters in the district, he had done so with misgivings, but after copies of the first batch arrived, he wrote her, “Your letters are splendid…I don’t think I have ever sent any better letters out of my office.” And when she began making occasional suggestions, he could hardly help starting to notice that they usually contained considerable insight, if not into politics, then into human beings; for example, they had decided jointly that she should include in her letters to constituents a reference to the fact that she was working without salary, but now she said she thought that was wrong—too self-serving. “I agree with you,” he wrote. He wanted her to do more work, and more, and more—because, he wrote her, if she could do enough, “we would be invincible.” There may have been some resistance in the office to taking orders from her, but on March 1 he sent a letter of “instruction about the staff’s future responsibilities” and had her read it to the staff, and after that there was no question about who was in charge. Then, after ten weeks, he returned and learned almost immediately that he was going to the South Pacific; sitting at his desk, he wrote out his will leaving everything to her, had O.J. and Mary witness it, and left. “I remember how handsome he looked in his Navy uniform,” Lady Bird says.

The next weeks were a bad time for her. There were few telephone calls, and they were from Hawaii and then from New Zealand, and then there was one from Australia in which her husband said he was about to go into the combat zone; the weather in Washington was warm, and the windows in the Johnson apartment would be open, so that Gladys Montgomery, who lived in the apartment below, was awakened when the phone would ring “around three or four in the morning,” and Mrs. Montgomery could not help overhearing the words with which Lady Bird ended each call: “Good night, my beloved.” Then, for some time, there were no calls at all; the next word was a report that her husband was in a naval hospital in the Fiji Islands, dangerously ill. There were weeks of worry.

During these weeks, she ran his office. There were no longer any instructions in the margin of a letter to help her, although with a particularly thorny question she could call John Connally or Alvin Wirtz, an attorney who was Johnson’s most trusted adviser, in Austin. She was on her own.

Every day brought some new problem to be solved. A relative of a constituent had died in Palestine, and a lawyer from Palestine was needed to handle the estate. When Lady Bird went to the State Department, she was told arrangements would have to be made through the British Embassy. (“I didn’t see the ambassador—I wasn’t that size of an applicant,” Mrs. Johnson says, “but I did get to see” an official, “a very nice gentleman, with courtly manners. He said, ‘Won’t you join me for a bit tea?’ and he reached into the drawer with an almost conspiratorial wink and took out two lumps of sugar and dropped one in my cup and one in his.”)

“There were always mothers who said they hadn’t heard from Johnny in months and months,” she recalls. “Would I please find out where Johnny was.” There were “a whole lot of folks who wanted to get into officer candidate school, knowing they were going to be drafted sooner or later.” There were the businessman with half-completed plants “so you had to plead their cause before the War Production board or whatever… ‘Strategic materials’ and ‘OCS’ and lots of things became just a part of your vocabulary.”

And she learned she could solve the problems. “You know,” she recalls, “the squeaking wheel gets the grease. And if you keep after the Army Department or the Navy Department or the Red Cross long enough and pester them enough, we could help them. For one thing, it was down the street from us, and it was sixteen hundred miles from them, so you could help them.” The constituent got his lawyer from Palestine, and Austin got its Air Force base, and a lot of Johnnys were located, and Lady Bird Johnson heard mothers sobbing with relief on the telephone when she told them that their son was alive, he just hadn’t bothered to write, you know how young men are.

She learned, moreover, that she could solve problems in her own way. She could never use her husband’s methods, but she could use her own. If she was a squeaking wheel, it was a wheel that squeaked very politely. Recalling forty years later the lessons she learned during the summer of 1942 about helping constituents, she said: “If you’ll just be real nice about it, and real, real earnest, courteous, and persistent, you could help them.” She never let her smile slip or raised her voice or said a harsh word, but she never stopped trying to solve a problem—and a lot of them were solved. Edward A. Clark, an Austin attorney who needed a great deal of help, both for himself and for his clients, with the War Production board and other government agencies, and who had not looked forward at all to having to rely on a woman, says: “When she took over that office, she was wonderful. She gave wonderful service… And she did it without ever raising her voice or fussing—she never shouted even at a secretary. She thanked anyone who brought her a pencil. She was just as sweet and kind to them. She was grateful to everyone.” And as she got the lawyer and the Air Force base and the other things the constituents wanted, Lady Bird Johnson got something for herself, too—something she had never had before: confidence.

“The real brains of the office were O.J. and Mary,” she is careful to say, in recalling 1942. “And yet I played a useful role.”

When, years later, she would be asked how the summer of ’42 had changed her, she would always, as was invariable with her, put the changes in the context of her husband. “The very best part of it,” she would say, “was that it gave me a lot more understanding of Lyndon. By the time the end of the day came, when I had shifted the gears in my mind innumerable times, I could know what Lyndon had been through… I was more prepared after that to understand what sometimes had seemed to be Lyndon’s unnecessary irritations.” When, at the end of the day, Nellie or someone else wanted her to make still another decision—where to eat dinner, for example—she would “get almost mad at them.”

But she also saw some changes that were not in the context of her husband.

“After a few months,” she says, “I really felt that if it was ever necessary, I could make my own living—and that’s a good feeling to have. That’s very good for you, for your self-esteem and for your place in the world—because, well, I didn’t have a home, and I didn’t have any children, and although I had a tremendously exciting, vital life, I didn’t have any home base, so to speak, except for Lyndon, and it’s good to know that you yourself, aside from a man, have some capabilities, and I found that out, er, er, er, to my amazement, rather.” During my interviews with her, Mrs. Johnson was invariably helpful, cooperative, pleasant, but she seldom showed the depths of her emotions. When the interviews reached 1942, however, Lady Bird Johnson suddenly blurted out: “1942 was really quite a great year!”

Speaking of the qualities that Lady Bird Johnson revealed for the first time while her husband was away at war, Nellie Connally says: “I think she changed. But I think it was always there. I just don’t think it was allowed out.”

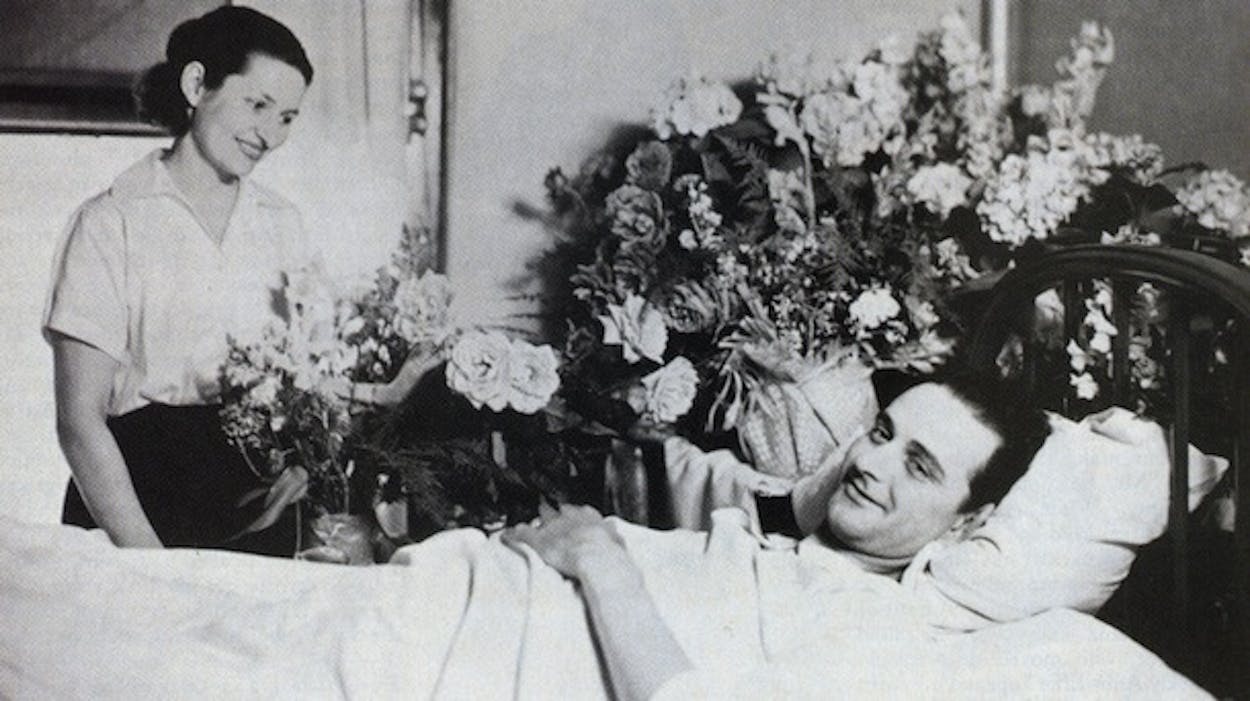

After Johnson returned from the war (“I was shaken when I saw him,” Lady Bird remembers. “He had been through a lot. He had lost weight…. My feeling was at once protective, and I just wanted to get him a lot of milkshakes.”), it was again not allowed out. Mrs. Johnson says that after her husband’s return, “I did not go into the office regularly.” Nothing could elicit from Mrs. Johnson’s lips one word that could possibly be construed as a criticism of her husband. Oh, no, she says with emphasis, she was not at all disappointed to stop working and return to her previous life. “I was glad to turn over the responsibility.” The turnover was complete. Any illusions Mrs. Johnson may have held about now being included in her husband’s political discussions were shattered at one of the first of those discussions, when she ventured to stay in the room after it began. “We’ll see you later, Bird,” her husband said, dismissing her. He treated her as he had before.

So impressed had Austin political and business leaders been with her that one day, Ed Clark recalls, when a group of them were at lunch, someone said—“kidding, you know”—“Maybe she’s going to decide that she likes that office, and then he’s going to wish he hadn’t gone off to war.” This joking became so widespread that it reached print in district newspapers; a letter to the Goldthwaite Eagle, for example, said that instead of reelecting Johnson to Congress in absentia, “I’d call a convention… and nominate Mrs. Lyndon Johnson for Congress to take her husband’s place while he is fighting for his country, and she would make a good congresswoman, too.” The joking reached Johnson’s ears—and after he returned, he took pains to put it to rest, to make clear that his wife’s role as caretaker of his office while he was in the Pacific, and indeed her role in his overall political life, had never been significant.

Lady Bird’s Aunt Effie knew how much her niece wanted a house, and now she told the young wife that she would pay most of the purchase price if Lady Bird found one that she wanted to buy. Moreover, there would be money from the estate of Uncle Claude Patillo of Alabama, who had recently died. By the fall of 1942 his estate was being settled, and Mrs. Johnson was informed that she would eventually be receiving about $21,000. “Now we can go and get that house,” she told her husband.

The two-story brick colonial at 4921 Thirtieth Place, a quiet street in the northwest section of Washington, was a modest eight-room house with a screened verandah at the rear, but she loved it. Her husband liked it too, but he insisted on bargaining and issuing ultimata to the owners. When they refused to accept his “take-it-or-leave-it” figure, the deal seemed dead. Coming home to their apartment one day, Lady Bird found her husband talking politics with Connally and asked if she could discuss the house with him Her husband listened to her arguments and then, without a word of reply, resumed his conversation with Connally as if she had never spoken. For once in her life—the only time in her married life that any of her friends can recall—Lady Bird Johnson lashed back at her husband.

“I want that house!” she screamed. “Every woman wants a home of her own. I’ve lived out of a suitcase ever since we’ve been married. I have no home to look forward to. I have no children to look forward to, and I have nothing to look forward to but another election.” In the retelling of this story, the denouement has a patina of cuteness. Johnson was reported to have asked Connally, “What should I do?” to which Connally is said to have replied, “I’d buy the house.”.This may not have been the actual dialogue, but by the end of 1942 the house was bought—for $18,000, about $10,000 of which Aunt Effie put up—and Lady Bird had her home. “You see,” Mrs. Johnson carefully explains, “I didn’t feel unhappy. I was happy about the house.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- LBJ

- Lady Bird Johnson