Introduction and annotations by presidential historian, Michael Beschloss, a regular commentator on ABC news and PBS’s The Newshour With Jim Lehrer and the author of the just-published Reaching for Glory: Lyndon Johnson’s Secret White House Tapes, 1964-1965. He is also the host and narrator of Lady Bird, a PBS documentary on Lady Bird Johnson that will air on December 12.

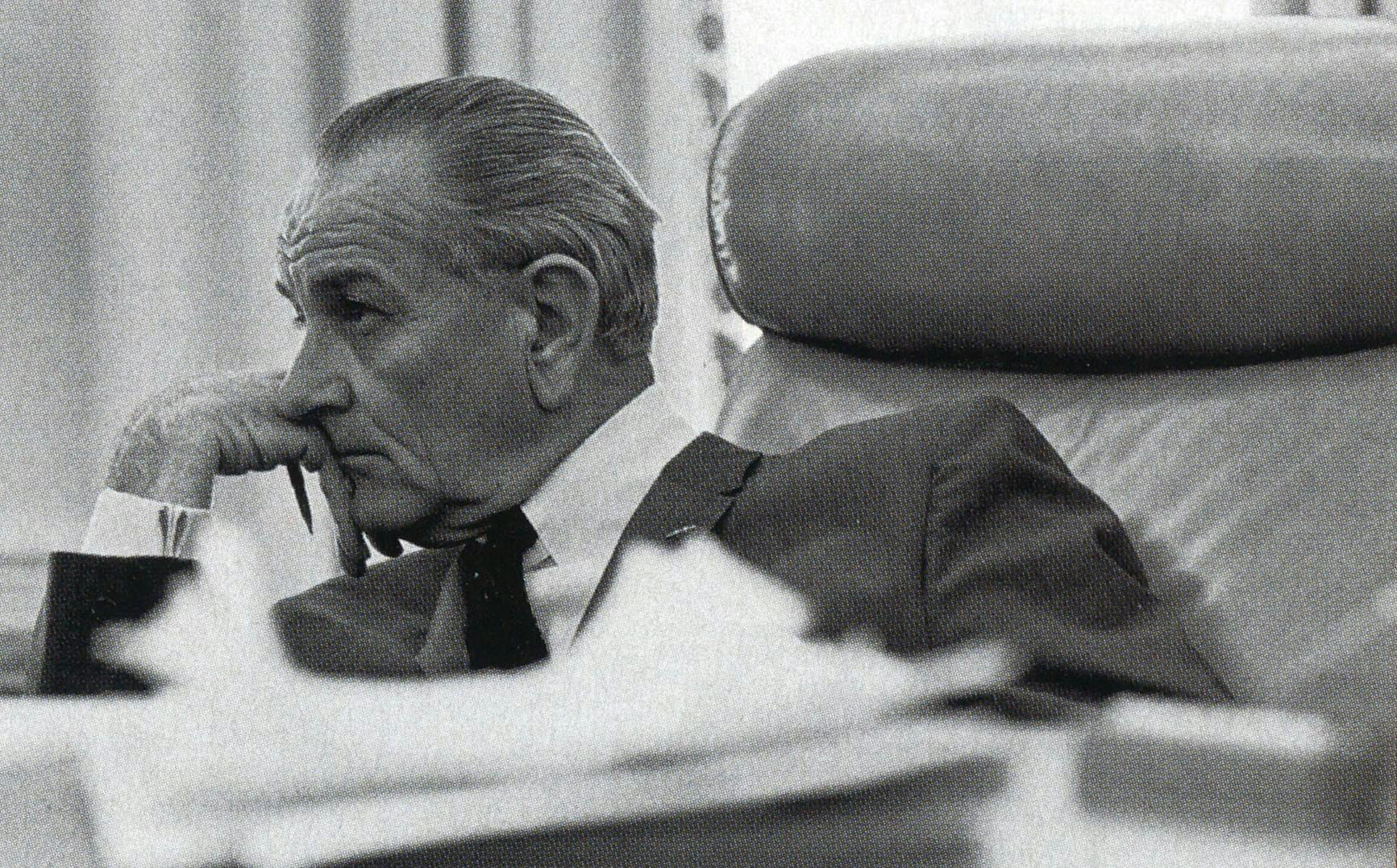

After Richard Nixon was inaugurated in 1969, former president Lyndon Johnson returned to the LBJ Ranch near Stonewall and set about writing his presidential memoirs, The Vantage Point, with the help of two of his speechwriters, Harry Middleton and Bob Hardesty, and a young political scientist named Doris Kearns, who had served as a Johnson White House Fellow. Middleton recalled that when they got Johnson to reminisce, he was “at his storytelling best … relating affairs of state as if they had happened in Johnson City.” He and his colleagues had hoped to capture LBJ’s language and idiom to give readers a sense of the appealing inner man. But not Johnson. As Kearns remembered, when he saw his words on paper, he said, “Goddammit! … Get that vulgar language of mine out of there. What do you think this is, the tale of an uneducated cowboy? It’s a presidential memoir, damn it, and I’ve got to come out looking like a statesman, not some backwoods politician.”

It was Johnson’s book, not theirs, and he got what he wanted. The result, published in 1971, was so leaden that much of it read like a parody of a presidential memoir. The New York Times observed that, from reading the book, LBJ’s life and administration must have been no more eventful than Calvin Coolidge’s. Johnson historians have always wished that some record of LBJ’s storytelling sessions while creating his memoirs had survived. I have always presumed that they must have had the flavor of the private Johnson I have been hearing on the secret White House tapes that I have been transcribing and editing since 1994.

As luck would have it, this summer Middleton found the transcript of one such session. He is retiring as the director of the LBJ Library in Austin in January 2002 and came across it while cleaning out his office. On August 19, 1969, at Johnson’s temporary office in the federal building in Austin, LBJ ranged over his whole life in front of a tape recorder. During later sessions, when Middleton and Hardesty tried to record him again, Johnson glared at the machine and barked, “Turn that thing off!” But thanks to this never-before-published transcript, we have an astonishing window on the real Johnson. Here are some of the best excerpts.1

Getting on the Ticket in 1960

More than forty years after John Kennedy chose LBJ as his Democratic running mate in Los Angeles, we still don’t know for certain how it actually happened. According to LBJ’s nemesis Robert Kennedy, JFK made a pro forma offer to Johnson, who was then the Senate majority leader, expecting him to refuse. When Johnson accepted, JFK sent RFK to Johnson’s Biltmore Hotel suite to get him to withdraw. Here is Johnson’s version:

In 1960 I knew I couldn’t get nominated [for president]. But there were lots who didn’t think so. Mr. Rayburn2 called me a candidate for president and opened an office. I closed that office. There were several reasons. One, I’ve never known a man who I thought was completely qualified to be president. Two, I’ve never known a president who was paid more than he received. Three, my physical condition.3 I just couldn’t be sure of it. I’ve never been afraid to die, but I always had horrible memories of my grandmother in a wheelchair all my childhood. Every time I addressed the [Senate] chair in 1959 and 1960, I wondered if this would be the time when I’d fall over. I just never could be sure when I would be going out.

Bobby [Kennedy] was against my being on the ticket in 1960. He came to my room [at the Biltmore Hotel] three times to try to get me to say we wouldn’t run. I thought it was unthinkable that [John] Kennedy would want me—or that I would want to be on the ticket as vice president. [After he won the presidential nomination John Kennedy] called me and said he wanted to see me. He came in [the next morning] and said he wanted me on the ticket. I said, “You want a good majority leader to help you pass your program.” I didn’t want to be vice president. I didn’t want to be president. I didn’t want to leave the Senate.

Rayburn told me the night before that he had heard they were going to ask me to run on the ticket. He said, “Don’t get caught in that one.” I said I had no plans to run—and that he must have been drinking to think that I had. So I told Kennedy, “Rayburn is against it, and my state will say I ran out on them.” Kennedy said, “Well, think it over and let’s talk about it again at three-thirty.” Pretty soon Bobby came in. He said Jack wanted me, but he wanted me to know that the liberals will raise hell. He said Mennen Williams4 will raise hell. I thought I was dealing with a child.

I said, “Piss on Mennen Williams.”

He said, “You know they’ll embarrass you.”

I said, “The only question is, Is it good for the country and good for the Democratic party?”

Prior to this, [John Kennedy] said, “Can I talk to Rayburn?” Rayburn was against it because the vice president is not as important as the majority leader. The vice president is generally like a Texas steer—he’s lost his social standing in the society in which he resides. He’s like a stuck pig in a screwing match.

Kennedy talked Rayburn into it. He said, “Mr. Rayburn, we can carry New York, Massachusetts, and New England but no Southern state unless we have something that will appeal to them. Do you want [Vice President Richard] Nixon to be president? He called you a traitor.” Rayburn always thought Nixon called him a traitor. Nixon brought me the speeches, and they contained a phrase “treasonable to do that” or something like that. I thought Nixon’s version was more just—but I lost that argument with Rayburn. Rayburn came in that morning and said, “You ought to do it.” I said, “How come you said this morning I ought to do it when last night you said I shouldn’t?” He said, “Because I’m a sadder and wiser and smarter man this morning than I was last night. Nixon will ruin this country in eight years. And we’re just as sure to have it as God made little apples.”

Dallas and the Assassination

As president, Johnson studiously avoided discussing the Kennedy assassination. Almost alone in refusing to be interviewed in person for The Death of a President,5 William Manchester’s history of the assassination that was written with the cooperation of the Kennedy family, LBJ insisted on answering the author’s questions in writing. He also refused to be questioned by the presidential commission he had appointed to investigate the murder, chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren; he provided a written statement instead. Wilder conspiracy theorists claimed that LBJ was closemouthed because he might have said things that could have tied him to Kennedy’s murder. In fact, even years later, Johnson was upset by his memories of the day and worried that talking about it would revive old controversies with Robert Kennedy over how well he had behaved.

Dallas has always been a nightmare for me. I’ve never discussed it, and I don’t want to think about it any more than I have to. I’ve only been in Dallas once since that assassination—to an REA6 meeting.

I was elected to the Senate in 1941 when I was 33 years old. That election was stolen from me in Dallas; they kept counting votes until W. Lee O’Daniel7 won. He was a nonentity and a flour salesman. When I accepted the vice president spot, I went to Dallas to speak, and there was great revulsion that I had joined the ticket with the pope of Rome. They spit on us. They knocked Mrs. Johnson’s hat off and said a lot of ugly things. That is pretty commonplace now, but it was new to us then. And it was in Dallas that we learned it.

I never wanted to go to Dallas in 1960, and things didn’t get any better there by 1963. Kennedy thought our [1964] election was in danger. I knew it was. The popular image of Texas is of billionaires and people with dollar bills coming out of their ears. He wanted to raise one million dollars [in Texas]. I guess two or three times he talked to me about it and said, “We’ve got that four-million-dollar debt to pay off.”

He had an appointment with [Texas governor John] Connally.8 Kennedy suggested that we come to Texas on my birthday [August 27]. The vice president’s relationship to a president is like the wife to the husband—you don’t tell him off in public. Kennedy mentioned four or five [Texas cities] he wanted to come to. Well, I’ve never raised a dime in Dallas in my life—never even carried Dallas. He felt each of those places could contribute $400,000.

Connally spoke up firm, clear, straightforward: “Mr. President, that would be the worst thing you could do. For the first thing, with you going in four or five places, everyone would say you are just interested in getting money. In the second place, that weekend at the end of August would be a bad weekend. All the rich folks will be up in Colorado cooling off, and all the poor people will be in Galveston and down around the Gulf Coast.” Kennedy wouldn’t take issue with him. He said, “I guess that’s right.” That ended it, and we went back to Washington.

The next thing, I heard Connally was in [Washington] at the Mayflower [Hotel]. He had a meeting with the president. Kennedy called Connally and said, “Come up—I want to visit with you.” After Kennedy told Connally what he wanted, Connally said he could work on [a trip to Texas at a later date]. Kennedy said, “Let’s set a definite date.” So a meeting was signed on. Connally came on out to my house [in northwest Washington] and told me what had happened. I said, “Why didn’t you tell me?” He said, “I assumed you’d be there [at the meeting].” Connally told Kennedy, “Don’t say anything about money. Make whatever speech you want to make anywhere in Texas and then just give one fundraiser in Austin.” Apparently, Kennedy agreed. Then we all went to work to raise money. Kennedy put Bill Moyers9 in charge [of the trip].

We had a good [visit] in San Antonio.10 It was hot, but it was pleasant. Then we went to Houston. It was also a pleasant meeting. A great deal has been made that the president and vice president had ugly words.11 Those were the figment of unbalanced imagination. The wish was father to the thought. When we got off the plane, the reception committee said Mrs. Johnson and I could ride in such and such a car. So we got in, and when we did, someone said, “Senator [Ralph] Yarborough is supposed to ride here.” So someone ran up to him and said, “You’re supposed to ride in this car.” Yarborough said no, he’d ride with [Houston congressman] Albert Thomas. Thomas was very anxious to be with Kennedy. Thomas jumped on the Secret Service car following the president. Then we came along. Yarborough rode with Thomas part of the way, not with us. I didn’t care, but the newspaper boys went wild. It was the biggest [thing] ever since [French president Charles] de Gaulle farted. There were headlines the next morning and all kinds of queries to [Kennedy press secretary Pierre] Salinger: “Was it true that Yarborough would not ride with the vice president?”

Shortly after we got to the [Rice] hotel, Kennedy called and said, “I wish you would come down and have a drink with me.” He had only his shorts on. Kennedy had a scotch and water or whatever it was he drank. I had a scotch and soda. Kennedy said he had been told about the incident with Yarborough. He said, “I told my staff people, ‘Tell him he either rides in the car or he doesn’t ride.’” I said, “Mr. President, it doesn’t make any difference.” He said, “Well, I just told them to tell him that.”

The Manchester book has it that we were heard to say loud words. Well, there weren’t any. I went downstairs with Mrs. Kennedy and then afterwards we went to the Thomas [testimonial] dinner. Then to Fort Worth. I got up early the next morning for breakfast. Mrs. Kennedy didn’t want to go to that breakfast.12 Her stomach was just not conditioned to raucous Texans so early in the morning. President Kennedy said it took Mrs. Kennedy longer to get ready and he made his reference to himself and to me—that no one could make anything out of us anyway.13 Then [inside at the breakfast] Mrs. Kennedy made her entrance, and she sat by me.

When Kennedy left, he said, “Come by my room.” I went up there. I had my baby sister and brother-in-law14 with me. She lived in Fort Worth. Kennedy was once again in his shorts. He called me to come in. He was putting on his shirt, walking around and talking. He put his arms in his shirt. That was the way he always dressed. He would put on his shorts and then put on his shirt. I would always dress the other way; put on my shorts, then put on my trousers. I had been raised to cover up that part of me first. I told my sister to wait in the hall.

He said, “How did you like that [comment] about us not taking any time to get ready?” He was looking for a compliment or a laugh about his little witticism. Presidents always look for that kind of thing, and people always give it to them. I said it was very nice. He said it was a hell of a crowd. I said it was. I told him my sister was out there, and he said, “Bring her in.” I took my sister in. He turned to her and said, “You’ve been awfully good to us in Fort Worth.” He then turned to me and said, “Lyndon, there is one thing I’m sure of—it’s that we’re going to carry two states in the election if we don’t carry any others, and those two are Massachusetts and Texas.”

We got to Dallas, got off the plane.15 Then I shook hands with the Kennedys when they got off their plane. Yarborough got into our car, and everything was very nice. We started to go down to the center. I was very impressed and very pleased with the crowds. Then we heard shots. It never occurred to me that it was an assassination or a killing. I just thought it was firecrackers or a car backfiring. I had heard those all my life. Any politician—any man in public life—gets used to that kind of sound. The first time I knew that there was anything unusual was when the car lunged forward. And at the same time, this great big old boy from Georgia16 said, “Down!” And he got on top of me. I knew then that this was no normal operation. Something came over the radio. No—I don’t know whether I really heard this or whether I’ve just read it and it impressed me so much that I assume I heard it. Anyhow it said, “We’re getting out of here.”

Youngblood was tougher and better and more intelligent than them all. Not all the Secret Service are sharp. It has always worried me that they weren’t. They are the most dedicated and among the most courageous men we’ve got. But they don’t always match that in brains. But the problem is, you pay a man four or five hundred dollars a month and you get just what you pay for.

Youngblood put his body on me. He did that all the way to [Parkland] hospital. When I got there and got out of that car, I had been crushed. I was under orders from him all the way. In situations like that, they’re in command, and you don’t question them. “In this door—to the right—here.” Just like it had been planned, every step of the way. When they’re good—and Youngblood was good—they’re the best you can find.

Mrs. Johnson wanted to see Mrs. Kennedy. And Nellie Connally. Then from there on, there were frequent conversations, and pretty soon they came back and said [Kennedy] was dead. It’s all vague in my mind who said what, and where, and who it was. But somewhere in my mind, I knew that this conceivably could be part of something even bigger. So I said, “Let’s get back to Washington as soon as we can.”

We went in an unmarked car, and I remember leaning over the back of the seat, all the way back. We went in Air Force One, just as they told us to. I called the attorney general [Robert Kennedy] from the plane, and I asked him if I should come back to Washington and take the oath. He said he would call me back, but he thought offhand I should take it there.17 He was calm and unexcited. [Deputy attorney general Nicholas] Katzenbach came on [the telephone]. The plane was full of people. We stepped into [the presidential stateroom] to get the oath from Katzenbach. I called a lawyer in Dallas, Irving Goldberg. He said he’d get Sarah Hughes.18 Everyone was saying, “Let’s get this plane off the ground.” I said, “No, we’ll wait for Mrs. Kennedy [to arrive with the late president’s coffin].”

![Texas senator Ralph Yarbrough (far left, next to John Connally) listens a speech in Fort Worth during Kennedy's trip to Texas. The media reported that Yarborough refused to ride in the same car as Johnson in a motorcade, and LBJ commented that the "newspaper boys went wild. It was the biggest [thing] ever since de Gaulle farted."](https://img.texasmonthly.com/2013/01/LBJ-0006.jpg?auto=compress&crop=faces&fit=fit&fm=pjpg&ixlib=php-3.3.1&q=45)

The Warren Report

In this passage Johnson is not quite leveling with his writers. From the day of Kennedy’s assassination, he had privately suspected that JFK was murdered by a conspiracy. In a post-presidential interview with CBS, he told Walter Cronkite that he had never been convinced that a lone gunman killed Kennedy. Immediately after the taping, he and his staff successfully pushed CBS to delete those comments from the broadcast version for reasons of “national security.” In my first volume on the secret Johnson tapes, Taking Charge,19 LBJ is told by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover the morning after Kennedy’s murder that the FBI had seen the suspected assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, at the Soviet embassy in Mexico City two months earlier. Worried that this news might leak out, poison American self-confidence, and cause Americans to demand military retaliation against Moscow that might cause World War III, LBJ was eager to appoint an investigatory panel that would offer an answer to the question of who killed Kennedy. He was also eager to derail demands for investigations of the crime by the FBI or at state and local levels. He was pleased when the Warren Report concluded that the culprit was a lone gunman, acting alone.

I had no question about the Warren Report. I am no student of it. All I know is this: I was no intimate of Justice Warren. I didn’t spend ten minutes with him in my life. But I concluded that this was something that Hoover and the Massachusetts courts and the Texas courts could not handle. We had to seek the ultimate to do the possible. And who is the ultimate in this country from the standpoint of judiciousness and fairness and the personification of justice? I thought it had to be Earl Warren, chief justice of the United States.

I knew it was bad for the court to get involved.20 And Warren knew it best of all, and he was vigorously opposed to it. I called him in [to the Oval Office]. Before he came, I was told that Warren had said he wouldn’t do it. He was constitutionally opposed. He thought the president should be informed of that. Early in my life I was told it was doing the impossible that makes you different. I was convinced this had to be done. I had to bring the nation through this thing. When Warren came in and sat down, I said, “I know what you’re going to tell me, but there is one thing no one else has said to you. In World War I, when your country was threatened—not as much as now—you put that rifle butt on your shoulder. I don’t care who sends me a message. When this country is threatened with division and the president of the United States says you are the only man who can save it, you won’t say no, will you?” He said, “No, Sir.” I had great respect for Warren. And from that moment on I was a partisan of his.

I shudder to think what churches I would have burned and what little babies I would have eaten if I hadn’t appointed the Warren Commission. If there was no Warren Commission, we21 would have been as dead as slavery.

The War in Vietnam

Here Johnson explains himself on the war. Intriguingly, he obliquely charges President Kennedy with complicity in the murder of South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem, which began the succession of coups that led to the questionable regime of generals Nguyen Cao Ky and Nguyen Van Thieu.

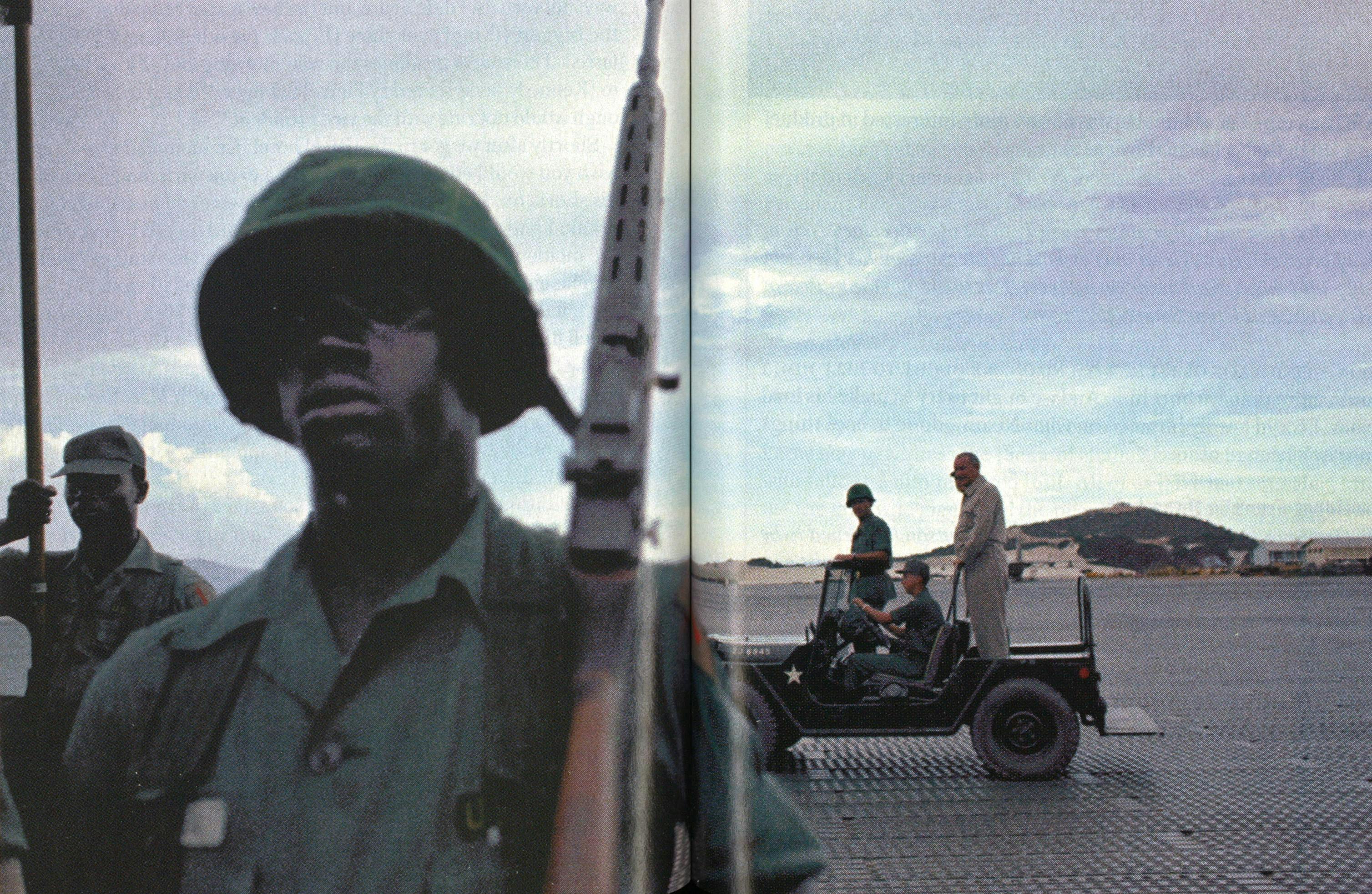

We started the day after we got back to Washington after Dallas to try to bring peace in Vietnam. Those first few days, Vietnam was on top of the agenda, before the visiting heads of state got home from the [Kennedy] funeral. We avoided the course this thing took and continued to avoid it until July 1965. [Secretary of State Dean] Rusk agreed that we ought to try to put a new face on things and make a new effort to see if the Communists were amenable to overtures for peace. I sent [Ambassador Henry Cabot] Lodge back to do everything he could.

They had just—with our encouragement—assassinated Diem before I went into office. We found it difficult to put Humpty-Dumpty together again. With all Diem’s weaknesses, it was not easy to tear that government apart and put it together again. Thieu and Ky emerged as leaders. We brought them [toward reform] about as fast as we dared. I’m afraid we’ve overstepped the [Vietnamese] constitution—speeding it the way we did. But I have no reluctance about those two men.

The [Communists] want what we’ve got, and they’re going to try to get it. If we get out, it will be tragic for this country. If we let them take Asia, they’re going to try to take us. I think aggression must be deterred. That’s just sound policy. I believe the big nations have to help the little nations. I think we ought to have stopped [Fidel] Castro in Cuba. Ike sat on his fanny [in 1959] and let them take it by force. I believe you’ve got to keep your guard up and your hand out. I want to be friendly with the Soviets and with the Chinese. But if you let a bully come in and chase you out of your front yard, tomorrow he’ll be on your porch, and the next day he’ll rape your wife in your own bed.

We had several bombing pauses [in Vietnam]. We indicated several things to the enemy, through India and other countries. If [North Vietnamese leader] Ho Chi Minh ever said anything but “Let them eat cake,” I am unaware of it. Our hope and prayer constantly was that maybe he’ll do something, but there was never any question of it. People say there’s nothing worse than Vietnam. Well, I think there are lots of things worse than Vietnam. World War III would be much worse. The good Lord got me through it without destroying any Russian ships, or Chinese. I constantly walked on eggs, one foot in China’s basket, one foot in Russia’s basket. One misstep could have kicked off World War III. “So help me God” were the happiest words I heard. When Nixon took the oath, I was no longer responsible for Vietnam or the Middle East.

The Decision Not to Run in 1968

Johnson explains his bombshell announcement not to run for president on March 31, 1968. He is eager to refute charges that he pulled out of the race out of fear that he would lose after Senator Eugene McCarthy’s surprisingly good showing in the New Hampshire primary and Senator Robert Kennedy’s entry into the race. To do so, he insists that his basic decision to stay out in 1968 had been made in 1964.

The morning of March 31, [1968,] Lady Bird came in and woke me up at five-thirty. She said, “[LBJ’s elder daughter] Lynda is going through a trying period. She just told her husband22 good-bye, and she’s an expectant mother. He’s going over there by your orders. He doesn’t even know what you’re going to say or do.” [Lady Bird] said we ought to meet her at the [White House] gate.

Lynda was coming on the red-eye special. We met her. We went upstairs and had a cup of coffee. She told us everything he had said, every little movement, where she kissed him. She looked at me, and she had tears in her eyes and her voice. She said, “Daddy, why does Chuck have to go and fight and die to protect people who don’t want to be protected?” It was hard for her to understand.

That night I looked over at Pat,23 who had his orders for [Asia]. The only doubt I ever had about the March 31 decision—the only thing that could have made me reverse it—was those two boys, or 200,000 more, saying I was a yellow-bellied S.O.B.

The best way I know to put it is this: My best judgment told me in 1964 in the spring—May or June—that if the good Lord was willing and the creeks didn’t rise, if we had the best of everything, I could get the job done. I could get my ideals and wishes and dreams realized to the extent I would ever get them realized by March of 1968. The odds were that I could survive that physically—but there was no assurance, and there were grave doubts.24

No one can ever understand who was not then in the valley of death how you were always conscious of that. I would see [President Woodrow] Wilson’s picture, and I would think of him stretched out upstairs at the White House.25 I would think, “What if I had a stroke like my Grandma did, and she couldn’t even move her hands.” I would walk out in the Rose Garden, and I would think about it. That was constant, with me all the time.

I told [New York Times columnist James] Scotty Reston [in 1965 that] I’d have [to enact my legislative programs] in six to eight months: “The Eastern media will have the wells so poisoned by that time that that’s all the time I have. They’ll have us peeing on the fire,” I said. “I don’t think any man from Johnson City, Texas, can survive very long.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower

The conventional wisdom of the time had it that as president, Eisenhower was somnolent and ineffectual. Here LBJ, who had served alongside Ike as the Democratic Senate leader for eight years, shows that he knows better.

I got the impression that columnists thought Ike was not exciting and didn’t know what was going on. I never saw this. I found his knowledge of men and events complete, [but] I disagreed with his evaluation of conditions often. He was too conservative for me, too admiring of some situations and rather prejudiced towards others. But he was filled with patriotism. He was a great help to me, and he was a balance to me often.

Senator Eugene McCarthy

LBJ is being slightly disingenuous here. As his secret White House tapes show, he seriously considered McCarthy for vice president in 1964.

I always thought of Senator McCarthy as the type of fellow who did damn little harm and damn little good. I never saw anything constructive come out of him. He was always more interested in producing a laugh than a law in the Senate.

President Richard Nixon

In 1969 Johnson was surprisingly friendly to his old adversary Nixon. He appreciated that Nixon was essentially carrying on his Vietnam policy and that he had made no serious effort to cut into the muscle of LBJ’s cherished Great Society programs.

I don’t find a lot of fault with Nixon. We ought to help him, I think, more than we hurt him. And we ought to try to make his load easier. I could hardly improve on what Nixon’s done to cool things since he’s been in office.

President Franklin Roosevelt

On October 29, 1940, Congressman Lyndon Johnson happened to be in President Franklin Roosevelt’s office when FDR’s isolationist ambassador to London, Joseph Kennedy—at whom Roosevelt was furious for his freelancing and his insufficient outrage against Adolf Hitler—returned to the United States. LBJ omits the detail that as FDR invited Kennedy by telephone for dinner, he drew his finger across his throat, razor fashion. Johnson twits Roosevelt for his indifference to civil rights, contrasting that unfavorably with LBJ’s own record.

I was with President Roosevelt the day he fired Joe Kennedy. He picked up the phone and said, “Hello, Joe, are you in New York? Why don’t you come down and have a little family dinner with us tonight?” Then he hung up and said, “That son of a bitch is a traitor. He wants to sell us out.” Well, Kennedy did say Hitler was right.

Anyway, Roosevelt didn’t have any Southern molasses compassion. He didn’t get wrapped up in going to anyone’s funeral. Roosevelt never submitted one civil rights bill in twelve years. He sent Mrs. Roosevelt to their meetings in their parks, and she’d do it up good. But President Roosevelt never faced up to the problem.

President John F. Kennedy

Six years after JFK’s death, Johnson still cannot figure out why Americans were so enamored of the man whom he had considered a backbench absentee senator of little promise.

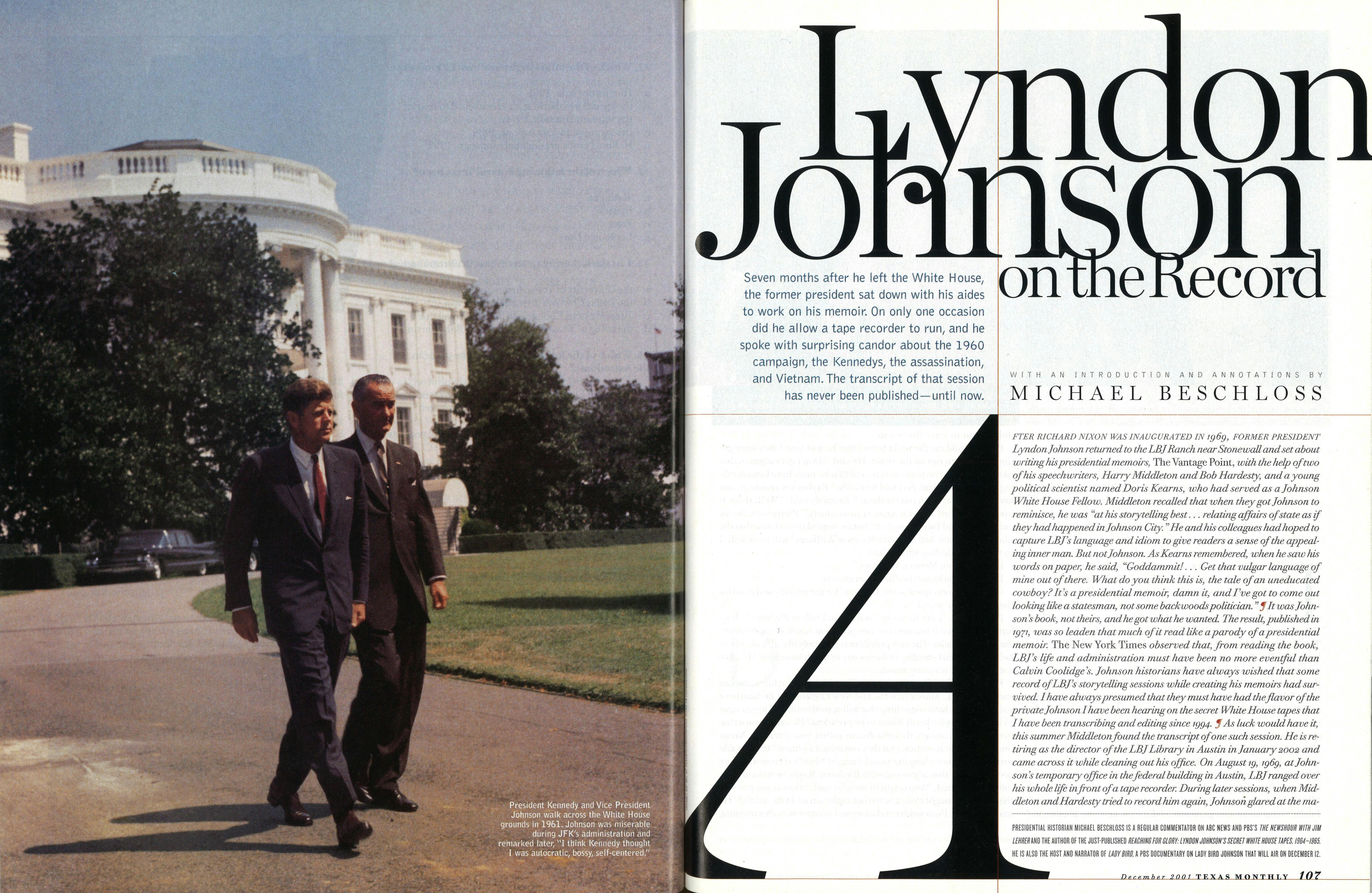

I think Kennedy thought I was autocratic, bossy, self-centered. Kennedy was pathetic as a congressman and as a senator. He didn’t know how to address the [Senate] chair. Kennedy had the squealers who followed him reported [on]. All of us have had squealers after us—the girls who giggle and the people who are just happy to be with you—but Kennedy was the only one the press saw fit to report on.

![President Johnson meets with Robert Kennedy at the WHite House in 1964. The two had a bitter political feud, and Johnson said, "I never did understand how the press built [RFK] into the great figure that he was."](https://img.texasmonthly.com/2013/01/LBJ-0005.jpg?auto=compress&crop=faces&fit=fit&fm=pjpg&ixlib=php-3.3.1&q=45)

Robert F. Kennedy

A year after RFK’s assassination, LBJ displays his abiding exasperation toward the man who had been his chief political enemy.

I never did understand Bobby. I never did understand how the press built him into the great figure that he was. He came into public life as [Joseph] McCarthy’s26 counsel and then he was [John] McClellan’s27 counsel and then he tapped Martin Luther King’s telephone wire. On civil rights I recommended to the president that no savings and loan association or no [FDIC] bank could continue if they did not make loans for open housing. Bobby called and said, “What are you trying to do? Defeat the president?” But the media was so charmed. It was like a rattlesnake charming a rabbit.

Getting His Name

I was three months old when I was named. My mother and father couldn’t agree on a name. The people my father liked were heavy drinkers—pretty rough for a city girl. She didn’t want me named after any of them.

Finally, there was a criminal lawyer—a county lawyer—named W. C. Linden. He would go on a drunk for a week after every case. My father liked him, and he wanted to name me after him. My mother didn’t care for the idea, but she said finally that it was all right; she would go along with it if she could spell the name the way she wanted to. So that was what happened.

I was campaigning for Congress in [inaudible]. An old man with a white carnation in his lapel came up and said, “That was a very good speech. I want to vote for you like I always have. The only thing I don’t like about you is the way you spell your name.” He then identified himself as W. C. Linden.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- Longreads

- JFK Assassination

- LBJ

- JFK