If Jim Hogan, the Democratic nominee for agriculture commissioner, had his way, his race against Republican Sid Miller would be determined using a novel approach. “I’d tell everybody to Google my name, and then I’d tell them to Google Sid Miller’s name,” Hogan says. “We could settle the whole election according to whose Google profile the voters found more appealing.” That may seem like a strange way to approach a political campaign, but Hogan is not your ordinary candidate. In fact, he’s the un-candidate of the year.

A farmer and insurance agent by trade, the affable 63-year-old Hogan is a familiar face in his hometown of Cleburne. Most days, you can find him hanging out at Burger Bar, a local institution about the size of a voting booth that first opened its doors in 1949, or at the local public library, where he whiles away the hours in his carrel, attending to business. He has never run for public office. He hasn’t raised a dime for his campaign. He didn’t attend the state Democratic convention. He doesn’t have a website. He does not even have a “Vote for Hogan” bumper sticker on his pickup. Why not? “I don’t like people to vote for someone ’cause their name is plastered on a car,” he says. “I just want to give everybody across the state something refreshing.”

The fact that Hogan has made it this far is surprising enough. Though the office of agriculture commissioner is relatively obscure to the average voter (the commissioner’s job is to oversee the Texas Department of Agriculture), it is a post that has been filled by some familiar names over the years, including Jim Hightower for the Democrats and Rick Perry for the Republicans. In the March 2014 primary runoff, Hogan defeated Kinky Friedman, the well-known musician, humorist, and cigar aficionado (and onetime columnist for Texas Monthly), but state party officials didn’t know what to do with him. They told Hogan he needed to raise money, but he rebuffed their advice. They told him he couldn’t win in November, and Hogan reminded them that the Democrats hadn’t won anything in decades. “I may just be your best candidate,” he told them.

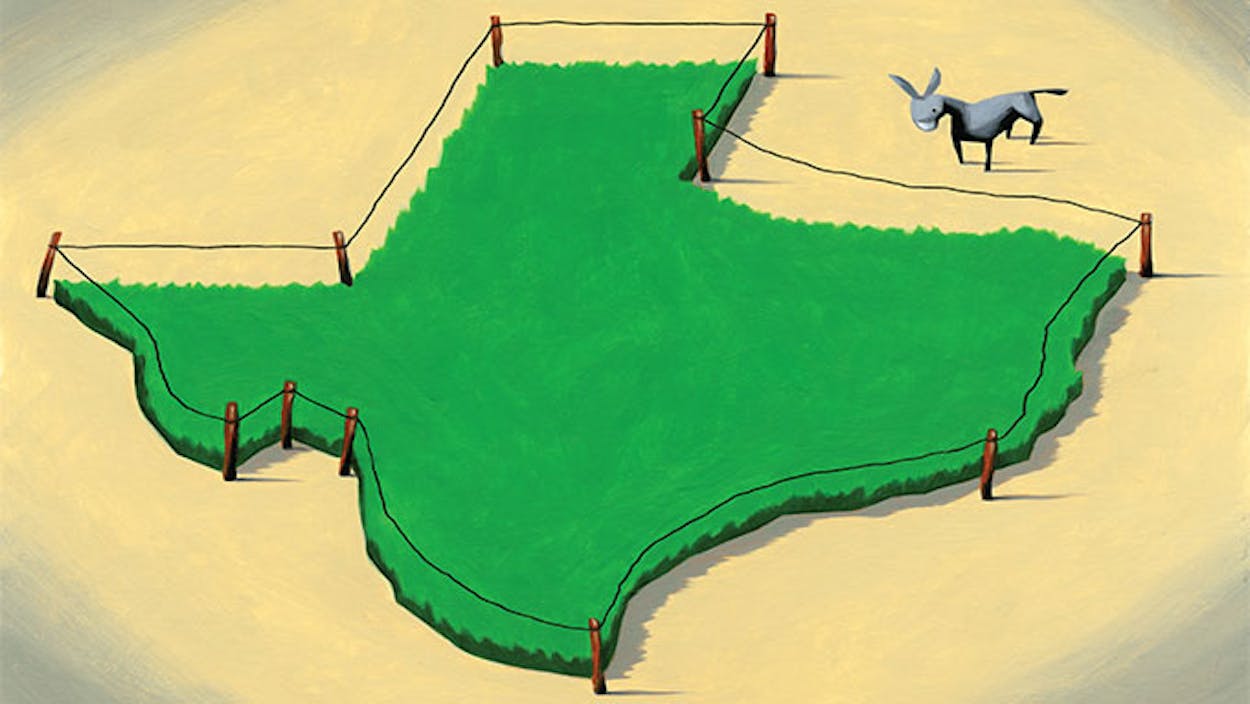

And all that helps illustrate just how barren the times are for the Democrats, who appear doomed to run one futile race after another. That is not to say that Wendy Davis and Leticia Van de Putte, the party’s nominees for governor and lieutenant governor, respectively, are not talented candidates. But based on all reasonable expectations, they are in no position to win in November. Still, a major party cannot run candidates like Jim Hogan for statewide office and expect to be taken seriously. I mean no disrespect to Hogan. He is a salt-of-the-earth fellow who would have been a great candidate back in the day when Texas was a rural state. He has three stock ponds on his farm where his neighbors are welcome to fish. He raises just about everything that the soil of Johnson County can yield, including watermelons, which he gives to his brother’s grandson to sell. One almost can’t help but pull for him. But he’s the last thing the Democrats need if they are ever going to play a serious role in state politics.

This election cycle is unlike any the state has seen in more than ten years, with several open seats, from governor on down, appearing on the ballot. This should have given the Democrats hope: it is their first real opportunity to catch the Republicans at a time of weakness. The GOP ticket has little star power. The party’s standard-bearer, Attorney General Greg Abbott, has run a lackluster campaign for governor, with carefully rationed public appearances. Dan Patrick, an ultra-conservative state senator who is poised to become the next lieutenant governor, has run a scorched-earth campaign based on social issues and a hard line on immigration. Ken Paxton, who is running to replace Abbott as attorney general, has been reprimanded for violating the Texas Securities Act and has spent much of the election out of sight. Glenn Hegar, the candidate for comptroller, is running on an ideological platform of doing away with property taxes and replacing them with sales taxes, a longtime dream of the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation that would make it difficult for local governments to function. That lineup has produced one of the most telling developments of the season: Rasmussen Reports, a polling firm that generally tends to be conservative, recently altered its assessment of the governor’s race from a double-digit lead for Abbott to a more modest eight-point lead and changed the outlook for the state from “safe Republican” to “leans Republican.”

But can the Democrats capitalize on that? For the first time since Ann Richards, the party has produced a well-known candidate for governor with a national following and the ability to raise large amounts of money. The question that must be asked is whether today’s Democratic party has the infrastructure necessary to win a statewide race—the money, the down-ballot candidates, the consulting talent, the PR muscle, the operatives, the issues research team, the number crunchers, who constitute the worker bees of a major political campaign—and all the other things that are essential to winning an election, the most important of which is finding sympathetic voters and getting them to the polls. All available evidence suggests that the answer is no.

How did things go so wrong for a party that dominated Texas politics for decades? The decline started with changing demographics. The old working-class neighborhoods in the big cities began to disappear in the sixties and seventies as their residents moved to the suburbs and took their votes with them. During that same time, an influx of people from the Northeast began to move to Texas and also embrace the suburban lifestyle. And why not? Everything in the ’burbs was new: the roads, the schools, the parks. The suburbanites didn’t need anything from the government, and they increasingly adopted the message of no new taxes and a conservative view on social issues. In short, the Democrats lost their constituency, and it has never come back.

If the arrival of newcomers from other states changed the political complexion of Texas, a similar movement from the south, involving a very different set of newcomers, had an even greater impact in recent years: wave after wave of Hispanic immigrants crossing the Rio Grande and settling in Texas. Immigration became the number one issue for Texas Republicans, and it remains so today. A new mantra made its appearance among GOP voters: “Secure the border!” Meanwhile, Democrats dreamed of a “brown wave” that would sweep over the state, but it soon became apparent that such a wave was not going to turn the tide in favor of their party. The Hispanic immigrants did not bring with them a sufficient interest in politics or the belief that government could help them, and they failed to show up at the polls in numbers that could have tipped the balance of power.

To their credit, Republican operatives like the state GOP’s chairman, Steve Munisteri, and political guru Karl Rove saw the need for rebranding the party and bringing Hispanics into the fold. But the party’s current leadership, Abbott and Patrick among them, have been blind to the hostility directed toward the state’s fastest-growing ethnic group. Abbott has antagonized Hispanics as a staunch defender of the state’s repressive voter ID law, and Patrick has loudly talked about stopping the “invasion” of Texas by immigrants.

The question Democrats have to ask themselves is why they haven’t been able to connect with voters in the past twenty years. As the state has moved further to the right, the party has been unable to produce a compelling narrative that explains what it means to be a modern Democrat. In many ways, they have allowed the Republicans, particularly those candidates and voters on the far right, to define them in the eyes of the electorate. Who remembers the message of Tony Sanchez, in 2002? Or Chris Bell, in 2006? Or Bill White, in 2010? Cycle after cycle, the Democrats have failed to capture the public’s imagination either by clearly defining the issues or by producing a candidate with the charisma and talent to excite the base.

Davis started off promisingly enough after she exploded onto the national scene because of the filibuster on the abortion bill. But since that time she has done very little to gain ground against Abbott. She has been through several rounds of staff changes, and it has seemed as if her camp has no strategic plan. She has never really gotten her sea legs as a speechmaker. And she is battling one of the biggest weapons the Republicans have: Barack Obama. His administration is a huge animating force for conservatives, and a doomsday scenario for Texas Democrats starts with an unpopular Democratic president in the White House. Bill Clinton is the only Democratic presidential candidate of recent vintage who has made a decent showing in Texas.

If there is an X factor in this election working in the Democrats’ favor, it might be Battleground Texas, an organization of poll workers who had ties with the Obama political machine and whose stated mission is to turn Texas blue. The problem is, Battleground is largely unproven and doesn’t have the confidence of top Democratic strategists. What remains to be seen is whether Battleground will be effective as it knocks on doors and blankets neighborhoods that fit the Democratic demographic or whether it will turn out to be just another group making a lot of noise with little to show for its efforts. The long-held notion that Texas may be on the brink of turning blue dominates conservative nightmares, but the reality is that, despite a shaky and uninspiring ticket, Republicans are in firm control of the state. And if Abbott and the rest of the ticket do indeed run the table in the general election this November, then you can expect them to remain in charge of state government for at least the next few cycles. It will be incredibly difficult for a Democratic challenger to knock off an incumbent in 2018, barring a scandal or some other dramatic turn of events.

Back in Cleburne, Hogan remains unfazed by all of this as he pursues his quixotic quest to be commissioner of agriculture. Like his fellow Democrat Victor Morales, the schoolteacher from Crandall who drove around the state in his pickup campaigning for the U.S. Senate in 1996, Hogan may soon become a footnote in Texas political history, but he seems comfortable with that result. “I hope my candidacy stirs good people to run,” he says, adding that even his daughter didn’t think it was a good idea. “She told me, ‘They’re not ready for your kind.’ ”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Sid Miller