The attorney general gazed out across the Bosque River Valley, took a deep breath, and raised his Remington 12-gauge shotgun. “Okay,” he called out. “Can I see one?” An orange clay pigeon flashed across the sky before disappearing into a field some forty yards away. He turned and laughed: “Can I see one more?”

It was a bright-blue mid-May afternoon, and Greg Abbott was relaxing with some of his old classmates from Duncanville High School, Billy and Buzzy and Randy and Rickey and Kevin and Joe. If those names sound like they come from Ward Cleaver’s America, that’s because they do. Abbott had a classic small-town upbringing; these are the friends he stayed up late with playing cards and dominoes before drifting off to sleep on backyard trampolines. The men have remained close over the years, happily recalling the times when they first tried chewing tobacco on a football trip to Corsicana or pulled an all-nighter while puzzling over the periodic table. The property, a gorgeous piece of land between Glen Rose and Hico, belongs to Rickey. Each year they try to gather here to swap stories, catch up on their families, and do a little hunting and fishing.

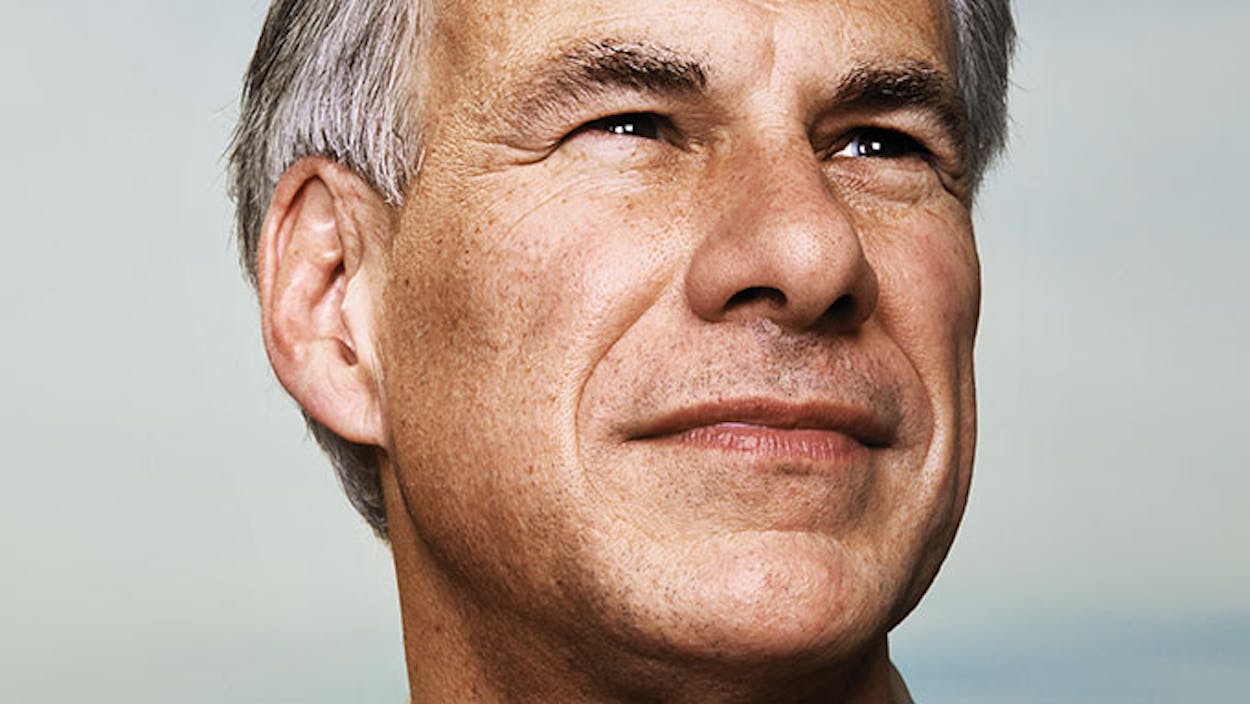

While one of the men adjusted the automatic trap, the 55-year-old sat in his wheelchair on a wide wooden deck and took in the view. He wore hunting boots, casual brown pants, and a gray short-sleeved shirt. “See that ridge over there?” he asked, pointing off into the distance. “Remember when we went out there and shot birds?”

“Well, shot at birds,” Rickey replied.

“That’s right,” Abbott said with a broad, easy smile. “A lot of birds went home happy that day.”

Soon the trap was ready, and the group grew silent. The attorney general raised his shotgun again. “Pull!” he cried.

The clay pigeon took flight at a more leisurely speed, and he squeezed the trigger. Boom! The pigeon sailed on, undisturbed. Boom! The target landed gracefully in the tall grass, fully intact. The group erupted with the kinds of jokes that high school buddies love to make at one another’s expense, even when one of them is the state’s highest-ranking law enforcement official. “Who gave Greg the box of blanks to shoot with?” Randy asked. Buzzy laughed. “This is where we do the Dick Cheney,” he said. “Better run!”

Abbott brushed them off and reloaded. “Pull!” This time, the moment the clay pigeon came into view, it exploded into a shower of orange bits. “Great shot, Greg!” went up the chorus.

He missed a couple, endured some more jeers, and hit a few more. After a while he called for someone to join him, and the games of knockout began. On his first round, he hit the pigeon, and as it came apart, he fired again and hit one of the larger fragments, an impressive shot. A few friends cycled through, then they switched games and fired at ten pigeons in a row to see who could shoot the most. Thirty minutes went by, then an hour, then an hour and a half. Abbott never stopped shooting. Once his friends had all had a chance, he called me over to shoot. I acquitted myself respectably. He then asked if the assistant to the photographer, who was there to take his picture for the magazine, wanted to give it a try. She agreed reluctantly, saying she hadn’t shot since she was a kid, but once she started, she never seemed to miss. From the back, Randy called out, “He’s the attorney general—you’re supposed to let him win.” But Abbott was having none of it. He offered her a wide smile and shook her hand. “That was terrific shooting,” he said.

The attorney general’s own shooting was, as a Boy Scout leader once told me at summer camp, “not too bad for the range, not so good if you’re under attack.” What was notable was his endurance. Everyone else took breaks; Abbott just kept blasting away. His shoulder, I caught myself thinking, is going to be black-and-blue tomorrow. Like many Texas politicians, Abbott has made guns central to his identity, but the intensity with which he does so seems at least in small part an attempt to balance out the fact that he is disabled.

No one can deny his toughness, which has come to define his career. A former track star at Duncanville High, he was nearly killed at the age of 26 during a freak accident while jogging. Ever since then, he has willed himself to extraordinary heights. A lawyer by training, he became a state district judge in the early nineties, then a member of the Texas Supreme Court, and finally the attorney general, in 2002. In all that time, he has never lost an election. Now he looks almost certain to continue that streak. He declared his campaign for governor in July, and while knife fights have broken out in several down-ballot races—the battle for lieutenant governor features a three-term incumbent fighting for his political life against three current officeholders—Abbott has escaped the prospect of a bitter Republican primary, drawing only a single, poorly funded opponent, former state party chair Tom Pauken. And by mid-September, no Democrat had yet declared for the race either. Despite the fact that a recent poll showed that 51 percent of Texas voters have no opinion of him, barring an unexpected twist, Greg Abbott will be the next governor of Texas.

That means he has already become the de facto leader of the state GOP, as Rick Perry, who will not run for reelection, rides off into the sunset. This transition comes at a critical time: the party is pushing further to the right on issues both social and economic at the same moment that sweeping demographic change and a faint heartbeat in the moribund Democratic party have made the long-term prospects for Republicans less clear. Though they control all levels of government in what is an inarguably conservative state, the pressure will be on Abbott to maintain that grip. If it loosens, he’ll get the blame.

Over the years Abbott has staked out positions that clearly define him as a conservative’s conservative. As he tells anyone who will listen, the attorney general has sued the Obama administration no fewer than 27 times. Earlier this year he described his typical workday as “I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home.” Or, as he puts it on the campaign trail, “I didn’t invent the phrase ‘Don’t mess with Texas,’ but I have applied it more than anybody else ever has.” He has successfully defended the placement of a Ten Commandments monument on the Capitol grounds before the U.S. Supreme Court and has threatened to file suit against the City of San Antonio for passing an ordinance in September that prohibits discrimination against people because of their sexual orientation. He has filed a brief with the Supreme Court arguing that the Second Amendment provides citizens with an individual right to bear arms. And he has gleefully battled perceived federal overreach in matters of environmental regulation, redistricting, and voter ID.

At the same time, he has tried to use his biography to soften those partisan edges. The pitch is simple: Because of his disability, he has a special understanding of the challenges facing all Texans—and the fact that he has accomplished so much is an indication that they can achieve great things too. Because his wife of more than three decades, Cecilia, is a third-generation Mexican American woman whose grandparents didn’t speak English, his family embodies the blending of cultures that is key to the future of Texas.

But does Abbott have what it takes to broaden the Texas GOP’s base and ensure its continued dominance? His daunting war chest of approximately $22 million provides ample evidence that many politically active people across the state think the answer is yes (Pauken, by comparison, has raised less than $250,000). Abbott’s fundraising totals, combined with a careful sequence of chess moves, have allowed him to capture the feeling that all politicians running for office desperately crave: inevitability. As the deliberate rollout of his campaign this summer made clear, he is both smart and cautious. “You know that scene in The Bourne Supremacy in which Jason Bourne uses his own passport and pops up on the grid?” says Jim Grace, an attorney for Baker Botts and an astute observer of the Capitol. “One of the agents tracking him says, ‘He’s making his first mistake.’ And another agent replies firmly, ‘It’s not a mistake. They don’t make mistakes. They don’t do random. There’s always an objective.’ Well, that’s how people think about Abbott and his campaign team. They don’t make mistakes.”

Still, the question remains: What should we expect from an Abbott administration? One afternoon, while traveling with him between campaign stops, I asked which Texas governors he would model himself after. He didn’t seem entirely comfortable with the question. In all the time I spent with him, he rarely paused to answer, but on this occasion there was a slight delay before he spoke: “My background is so completely different from previous governors that my administration will be unique.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott