If your property taxes are too high, blame the Legislature and the shell game it plays with public school finance.

First, let’s back up. The property tax/school finance intersection is a complicated beast and one that deserves a little unpacking. To start, property taxes are not a state tax; property taxes are paid annually by homeowners and collected by local school districts instead of the state. Even if you don’t own a house, you pay property taxes; a portion of your rent goes toward taxes paid either by landlord or your apartment complex, which is on the hook for the property taxes collected on commercial real estate.

Because Texas has no income tax, school property taxes and the sales tax—both of which everyone in the state pays in some capacity—affects the lives of Texans more than any other source of government revenue. To put it in perspective, if property taxes were a state tax, the $28.1 billion collected by the state’s school districts would make property taxes the second-largest tax in Texas behind the sales tax. It’s not just the rising market value on homes that drives the wealth, but every new skyscraper office tower also drives up a district’s taxable wealth.

As I said, property taxes are collected by local school districts—but it’s the Legislature that makes the rules on how those funds are distributed. And the rules are a complex school-funding formula that has put a greater burden on property-tax payers to pay for the state’s public schools while simultaneously reducing the state’s share of the expenses.

This extra burden is not felt by all taxpayers, though. If you live in a poor part of the state, your property taxes may actually decline, and in rural areas with relatively stable values, the taxes may stay about the same.

But, if you are in a high-growth area with rising commercial and residential values—say, Austin or Dallas or Houston—you may find yourself living in a school district that is not only subsidizing poor school districts but also the Legislature’s commitment to those school districts.

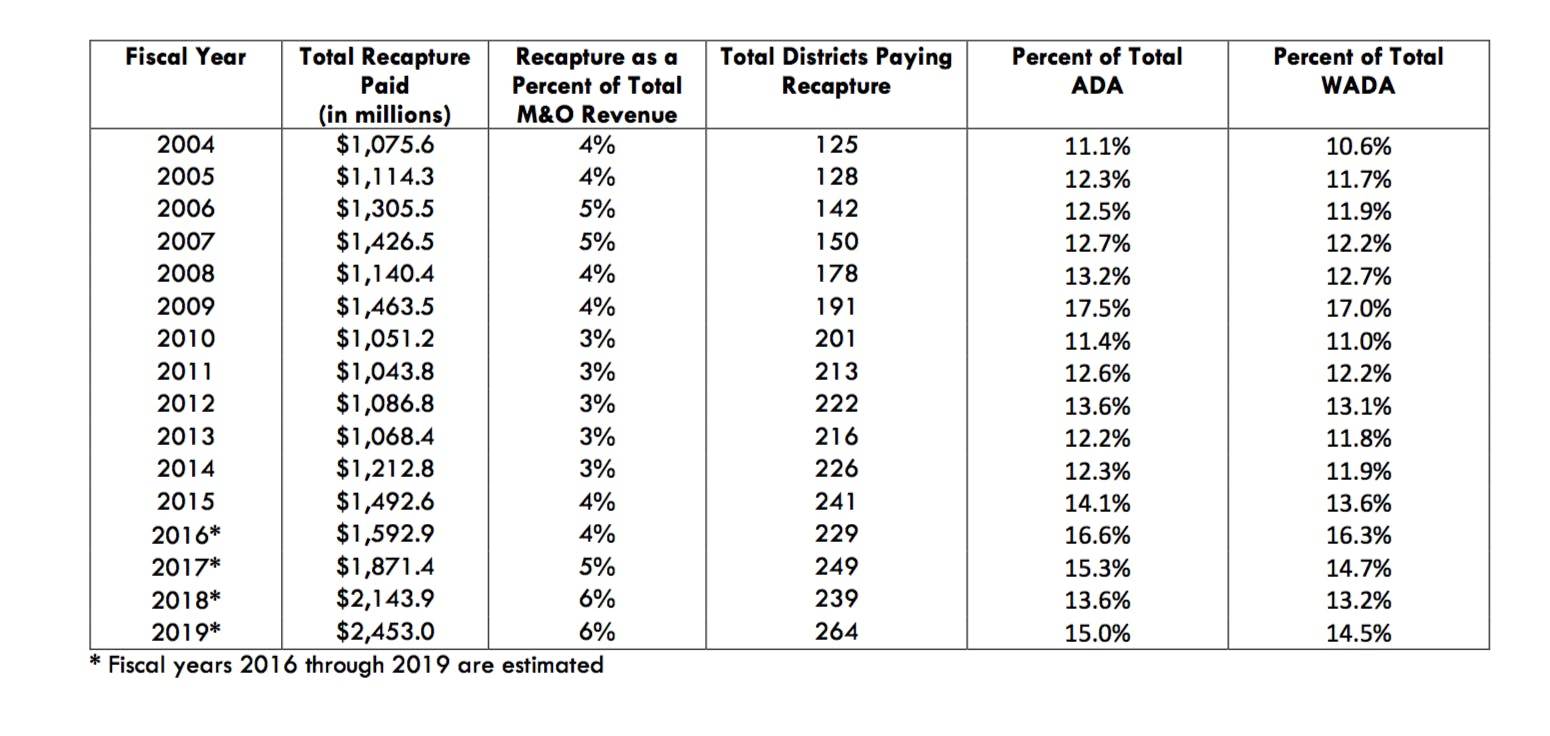

Since the early nineties, the state has had a system of “recapture” or “redistribution” to capture some of the tax revenue of high-value districts and give the money to low-wealth districts to pay for schools, a system known as Robin Hood. So who gives money to the state’s Robin Hood system? A decade ago, the state-sanctioned mythical highwayman took part of the local property taxes collected by 142 school districts; today, the number of districts contributing to this recapture fund is 229, a figure that will grow to 264 by 2019 if school finance reform does not occur.

As property values go up across Texas, more districts fall into the wealthy category. This creates two issues: 1) it takes money away from “wealthy” districts, which are not always so wealthy, and 2) it lowers the state’s obligation to pay for public education. This, of course, is to the benefit of the state’s budget writers.

This is coming home to roost, to a degree, in two of the state’s biggest districts. For years, one of the basic unwritten rules of public school finance in Texas has been that Houston and Dallas are exempt from having the state take some of their local taxpayer revenue for redistribution to other school districts. They’re so big with such a diversity of ethnicities, wealth, and poverty that they are like their own education principalities.

When the state Supreme Court ruled last year that the system of school finance is constitutional (while lamenting in the written opinion school finance’s sorry state), nothing better demonstrated just how broken the system is as the fact that Houston, for the first time, will become a property-wealthy district this year and will have to give a portion of its property tax collections to the state. Dallas is only about two years behind. No longer principalities, Houston and Dallas are now supplicants to the state budget writers. This means the state will take local money away from these ISDs, which both support a majority of low-income students and schools.

The Houston saga began last year when the district learned that, for the first time in its history, it owed a $162 million payment into the Robin Hood fund. In a vain effort to force the Legislature into school finance reform, Houston voters last fall decided to not make the payment and instead allowed the state education commissioner to permanently take $18 billion of commercial property off the HISD tax rolls and assign it to other school districts for taxation. While what we have been talking about is the taxes raised to pay for school maintenance and operations, if the real estate is off the HISD roll, it no longer would be available for additional taxes to build new schools. The gambit did not work, and suddenly Houston was racing toward a summer deadline when it would lose its taxable real estate.

In the meantime, the district’s lawyer, David Thompson, found a loophole in state law that allowed state education commissioner Mike Morath to lower HISD’s bill to either a $77 million payment or the loss of $8 billion in taxable property. Last week, the Houston school board set a special election for May 6, asking voters whether the district should write the check or give up commercial real estate to another district for taxation. Board members called it a partial victory. Not everyone felt that way, according to the Houston Chronicle:

About 10 speakers at Thursday’s meeting lambasted the idea of the board reversing its stance on paying the recapture money. Ken Davis, principal of Yates High School, said the TEA’s lessening HISD’s recapture bill is not a favor.

“That’s not a gift -they’re still taking money from our schools,” Davis said. “Push back on that. You are all standing at a time where you set a standard for what the rest of the state does. Stand up and take a step forward.”

When the 2017 legislative session started, House Speaker Joe Straus said he was willing to take up school finance reform, but Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick said it was too complex for a regular session. The problem for Houston was that waiting for a special session would mean missing the deadline and losing the commercial property from the district’s tax rolls forever.

The Thompson loophole will save about 40 wealthy school districts approximately $40 million in tax payments to the state. It involves how property values are calculated on local option homestead exemptions. If a school district has rising values but is not part of the recapture system, its local option homestead exemption counts against it and the state reduces the funding the district receives from the state’s coffers. If a district raises rates to generate more money locally, the state also reduces how much money it gives the district. Once again, state budget writers are the ones who get a break.

“Recapture is real obvious. It’s the visible part of the iceberg. It’s the part above water,” Thompson told me. “Think about all the (other districts); that’s the part of the iceberg below the water. If my values go up locally, my taxpayers may pay more money to their schools, thereby thinking the schools have more money . . . What people don’t know is I’m writing a bigger check locally and the state is very systematically reducing state aid to offset that increase at the local level. So rising property values locally just frees up state money to be spent in areas other than education.”

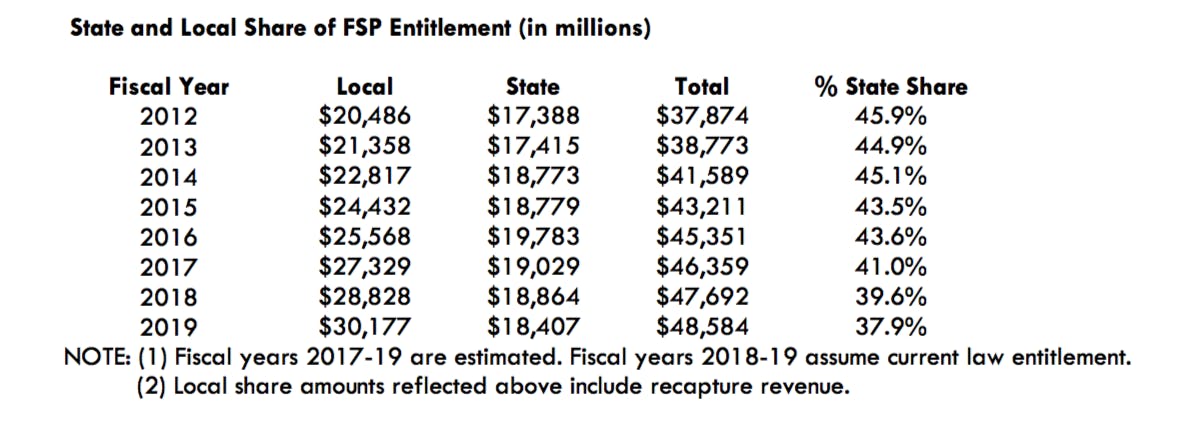

Just how much money does the increased appraisal on property in your school district and elsewhere save the state budget writers? The projection is $1.5 billion for the next two-year budget. And where does this money go? In its initial budget, the Senate plans to use the savings on other state expenditures. The Straus starting-point budget includes giving the money to the public schools, but only if a school finance reform passes. But even if the $1.5 billion is put back into the school system, the state’s share of funding the public schools will decline to 39 percent by 2019 without a major boost in state spending.

That figure does not include the $3.8 billion that the state will recapture from property-wealthy school districts over the next two years to redistribute to low-wealth school districts. (That amount is about equal to what the state collected in oil-and-gas severance taxes in the current two-year state budget, or to the taxes collected on alcohol and tobacco combined, or about twice the tax motorists paid to fill the tanks of their cars and trucks.)

In the meantime, a program that was meant to keep school districts from losing money because of 2006 property tax cuts is set to expire. A decade ago, state legislators wanted to make certain that no school district had its budget cut because of state-mandated tax cuts, so they set up a program called Additional State Aid for Tax Reduction. Originally, they intended the program to phase out as property values rose. But faced with a budget crunch in 2011, the Legislature put an expiration date on the program: September 1, 2017. When the program expires, it will leave 175 school districts faced with having to raise taxes or cut budgets to make up for $225 million in lost state funding. For the 55,000-student Frisco school district near Dallas, that means a $30 million budget cut, while the 100-student Webb Consolidated on the border will lose $4.3 million in state funding – 66 percent of its total operating budget. Losing the state tax-relief funding is a hardship for the districts; for the state’s budget writers, it’s just another $225 million they won’t have to finance.

“Even though the state is working to say, ‘We want to provide property tax relief,’ they benefit from higher tax rates and higher tax efforts made by the locals,” Christy Rome, executive director of the Texas School Coalition, told me.

Let’s face a big fact: educating the children of Texas is a massively expensive operation. In the 2015-16 school year, there were about 5.3 million children in the public schools, and almost 59 percent were economically disadvantaged. If the Texas system of public schools were a state, it would be bigger than the population of South Carolina and about equal to the populations of Maine, New Hampshire, Hawaii and Idaho combined. State budget authorities are projecting an increase of 82,000 students a year over the next two years—that’s more children entering the schools than there are people living in McKinney, Pasadena, or Waco. This rapid increase in the student population drove local, state, and federal spending on the Texas public schools to increase by almost $10 billion since 2008, from $41 billion to an estimated $51 billion in 2017; yet, if recalculated for constant dollars that combine the state’s population growth with inflation, the total spending on public education has declined from $40 billion to $38 billion during that same time period.

Throughout this, many school districts are faced with a state finance system that is a no-win proposition for them—and a big win for state budget writers.

To illustrate the point, Plano ISD last year sent Governor Greg Abbott a letter explaining, how as a property-wealthy district, rising values did not increase funding for local schools even though local property owners were paying higher taxes. In the 2015-16 school year, the PISD collected $470 million from local taxpayers, sent $52.6 million to the state for redistribution, and kept $417.6 million to pay for local education. If the district did not change its tax rate, rising values would push tax collections up by almost $40 million, but the state would now take an additional $43.6 million in recapture and leave the district with $5 million less to pay for schools.

The district could cut the tax rate so that total tax collections stayed the same, but the formulas would still take an additional $25.6 million because of rising property values and leave Plano with $392 million to run its schools—a $25.6 million cut from the previous year.

The other idea was to give taxpayers some relief by adopting a $10,000 local option homestead exemption while leaving the tax rate unchanged. But even this proved problematic for PISD: the district would raise another $30.2 million in total property tax collections and boost the transfer of funds to the state by $43.6 million, all while leaving the district with $13.4 million less to pay for schools.

No matter how it was calculated, Plano taxpayers paid more, the state reaped cash that lawmakers could use to reduce how much they had to spend on public education, and the schoolchildren of Plano were left with less money to pay for their education.

“For full disclosure, non-(wealthy) districts realize the same net impact,” wrote Missy Bender, Plano’s school board president. “The only difference is that when their property values grow, the state benefits by reducing their state funding rather than sending them a bigger state recapture tax bill. Either way, when property values increase, the true beneficiary of additional operating revenue is the State of Texas – not local school districts.”

The Spring Branch school district sent a very direct letter to taxpayers in 2015 outlining the same kind of math. “This year, taxpayers will pay $32 million more to SBISD from increased property values. SBISD nets only $2 million,” wrote Scott R. Muri, SBISD’s superintendent. “We continue to feel it is misleading for local taxpayers to write checks to our local school district when the majority of the funds attributable to local value growth actually benefit the bottom line of the State’s budget.”

Austin ISD’s chief financial officer, Nicole Conley, testified to legislators last fall that her district will pay the state $406 million in recapture payments this year, an amount equal to $1,400 in local property taxes. Between 2016 and 2020, she said, the district will pay $2.6 billion into financing the state’s schools. More than half the district’s tax revenue will go to the state in 2019, Conley said. The district has less money to spend per student now that it did before the massive budget cuts of 2011, and this is in a district where almost two-thirds of the students live in poverty and 28 percent are learning English.

But if the district raised taxes, more than 60 percent of the new revenue would go to the state. “Unfortunately, the state’s over-reliance on recapture is leading to an unintended inequitable burden for some communities’ taxpayers who are shouldering much more of the expense to educate our state’s children,” she said. “We know there are districts throughout the state that need additional fund to educate their students, but it is the duty of the state to provide those funds, not local property taxpayers.”

State funding of public education has grown by about $2.7 billion over the past two years—but that’s to cover an increase of about 85,000 students a year in the school system. The overall funding formulas, though, have allowed the state to reduce its share of the total cost and shift it to local property taxpayers.

This was evident in a graphic provided by the Legislative Budget Board to the Senate Finance Committee last month. In 2012, the state paid 46 percent of the cost of public education; by the end of this year that will have declined to 41 percent. If the Legislature does nothing for the next two years other than finance enrollment growth, the state share will go down to 38 percent by 2019. During that time period, local school districts will have increased their share of spending by about $10 billion, while the state’s share will have gone up $1 billion. Throughout this article I have focused on the impact on property tax payers—whether they are homeowners, a refinery, or a person who owns a pump jack in West Texas—the fact that the state shortchanges the system also has a negative impact on the property-poor districts.

In fairness to the Legislature, they wrote legislation in 2015 to increase the state-mandated homestead exemption from $15,000 to $25,000 and appropriated $3.9 billion to make up for the revenue lost by the school districts. But they also approved a franchise tax cut for business; this took $2.6 billion out of the state property tax relief fund that was set up to cover tax cuts passed in 2006. So when Governor Abbott said in his State of the State address to the Legislature last month, “We must continue to cut the business franchise tax until it fits in a coffin,” he might as easily have said, I want to cut business taxes to put even more of the burden of paying for schools on property tax payers.

Governor Abbott did offer support for Senate proposals to limit property taxes by cities and counties. However, according to the state comptroller’s office, cities, counties and special districts collect only 46 percent of all the property taxes in Texas, while school districts collect the remaining 54 percent. If Abbott and Patrick and Straus really want to reduce local property taxes, they’ll have to step up like former Governor Rick Perry and other state leaders did in 2006: sometimes you have to raise other taxes to cut property taxes.

Disclosure note: My wife is a long-time employee of the Texas Education Agency. We did not consult on this column, and it does not reflect either her opinion or that of the state agency. It is only my own from thirty years of covering the state budget, public school finance, and state taxes.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Public Schools