I see Ross Perot as a throwback, a distinct cousin to two types of 19th century mythical American heroes. In his deeds, Perot is as gargantuan—as wonderful and awful and ridiculous—as Davy Crockett. In his idealisms, Perot would fashion himself, and the rest of us, after one of the proper and patriotic boy heroes dreamed up by the Rev. Horatio Alger.

Alger always began by investing his hero with the proper boyhood values—values which were personified by the Boy Scouts of America. Cheerful, brave, clean and reverent, those were good values for boys, suitably child-like and simplistic, which is about all a kid—and a lot of adults—can handle.

Anyway, to get on with our story, Perot continued in the Algerian mold through college. The Boy Scout with all the merit badges became the best-all-round midshipman at Annapolis, twice elected president of his class. After four hard-working, hustling years in the Navy aboard ships, he left to earn fame for himself in American business.

Here, Ross Perot begins to nudge a little against the outlines of an AIger hero, begins to show a little too much flamboyance. He is a salesman for IBM and he is selling too many computers and business machines. Management must do something! After four years, they sit on him, put a ceiling on commissions a salesman can make in a year. But a Perot down is not a Perot defeated! He makes his year’s limit in 19 days! Then he gives them the finger. Quits.

Here he has left Horatio Alger behind and has become a man in the monumental mold of a Davy Crockett. Davy was too big for Tennessee as Ross was for IBM. Both went off in search of bigger bear. Davy took his rifle and went to the woods. Ross took $1000 and went on his own into the corporate jungle.

Within a few years, both were legends. The man of action has always been number one in the hearts of the American people, whether it’s killing bears in the woods or making a killing on the market. What Perot did was not only sell computers, he sold the whole system, programming, operation and maintenance—and everyone said he was crazy, just as they dared Davy Crockett to run for Congress. But Perot pulled it off in stunning fashion, until by 1969 his stock in Electronic Data Systems (EDS) was worth (on paper) more than one billion dollars. This is roughly equivalent to a U.S. congressman killing 109 bears, which is what Crockett did during a nine-month period in 1826.

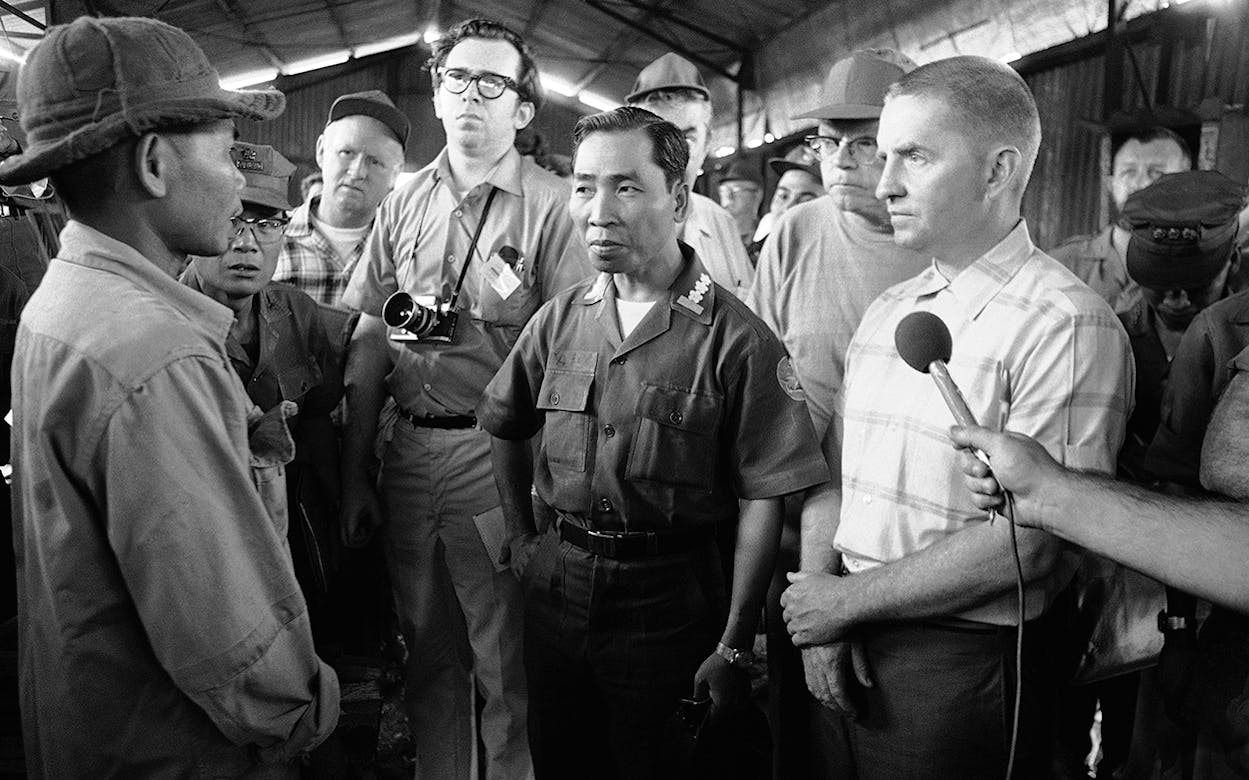

One Bunyanesque deed calls for another, especially if you are a Boy Scout committed to doing a good deed a day (Ross Perot, at 43, is regional president of the Boy Scouts of America.) Thus he decided, five years ago, to do the greatest good deed of all, to marshal the American people behind President Nixon’s Vietnam policy and to do all he could to hasten the return of American prisoners of war. He set up United We Stand and hired newscaster Murphy Martin as its president. The thinking behind United We Stand went something like this: If the Vietnamese Communists really understood how solidly the American people are behind President Nixon’s policy, then they will relent and not only give up the prisoners but give up the war. It is said that Ross Perot spent two million dollars on United We Stand before it disbanded. Its effect on the North Vietnamese seems negligible.

If Perot puzzled us, think what he must have done to the enemy envoys. Everytime they would close the door on him he would ante up with another offer. Okay, he said, I’ll tell you what I’ll do. You release the prisoners and I’ll rebuild your hospitals and schools destroyed by American bombs. His word was backed by fifty million in a Bangkok bank. Of course they didn’t take him up. Some great capitalistic joke, they must have said to one another.

Much as Crockett did, I think Perot has begun to read and act out his own legend. Ultimately, a man such as this sees himself as a symbol of America and Americans, a living testament, as it were, and all his acts, thereafter, are writ in patriotic terms.

The Horatio Alger in Perot drinks soft drinks and is strong and upright in adversity. When he lost more money than any American has ever lost on the stock market, when his EDS stock dipped from 1.5 billion to 160 million, he did not flinch. Does money mean anything to Ross Perot? I think not as much as the pursuit of it, which keeps him lean and alive.

Perot also has a program for America. He would make the worker a capitalist by allowing taxpayers to accumulate $100,000 in tax free capital gains over a lifetime. He would have Americanism taught in the schools—his own brand, of course, and more often than not he puts his money where his mouth is. He is a Presbyterian who gave $150,000 to Catholic schools; a rich Anglo who gave $1 million to the Boy Scouts with the stipulation that they use the money to recruit the poor and the minorities.

In a simpler time in America, when Sinclair Lewis strode the Main Streets looking for stereotypes, Ross Perot would have been looked upon as a paragon of good American values.

But these are not simple times and simple times may never return, which brings us to the relevance of Mr. Perot’s idealizations in today’s world. They are positive, but they are also pat, and seemed to be patterned after Fourth of July orations. In his company he hires with a 1950 conformity in mind and enforces what would be considered straight dress codes. Behind his desk is a plaque which reads: “Eagles Don’t Flock; You Have To Find Them One By One.” Certainly Ross Perot is an eagle, alone and individual unto himself. But does he permit eagles in his organization?

Now Perot’s Wall Street venture has gone down the drain, and veterans on the Street blame the failure on Perot’s attempts to pattern brokers after his platoons of computer program experts. “Wall Streeters are individualists,” said one brokerage official. “You can’t do that to them. His biggest mistake was trying to tell people how to run their own affairs. When he started to regiment people, he began losing a lot of good salesmen.” Shades of Ross Perot at IBM!

In retrospect, which is a damnable substitute for derring-do, saving Wall Street was a brave but foolhardy mission for Perot, much like Davy Crockett making his stand at the AIamo. At the last minute, Perot realized it and pulled out, sent up the white flag, which is what Davy did. I know traditional Texas history has Davy fighting to the death, but Mexican historians, while speaking of his courage, record that Crockett surrendered. He was taken before a firing squad and shot. Perot was sent packing to Dallas, a defeated visionary.

Is he diminished because now we see him as a tilter at windmills, a beautifully bizarre man who sticks out his neck and gets it chopped off? Yesterday I said yes, but now I say no. Perot the quixotic and eccentric individual I salute, no matter how short his heroics fall.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ross Perot