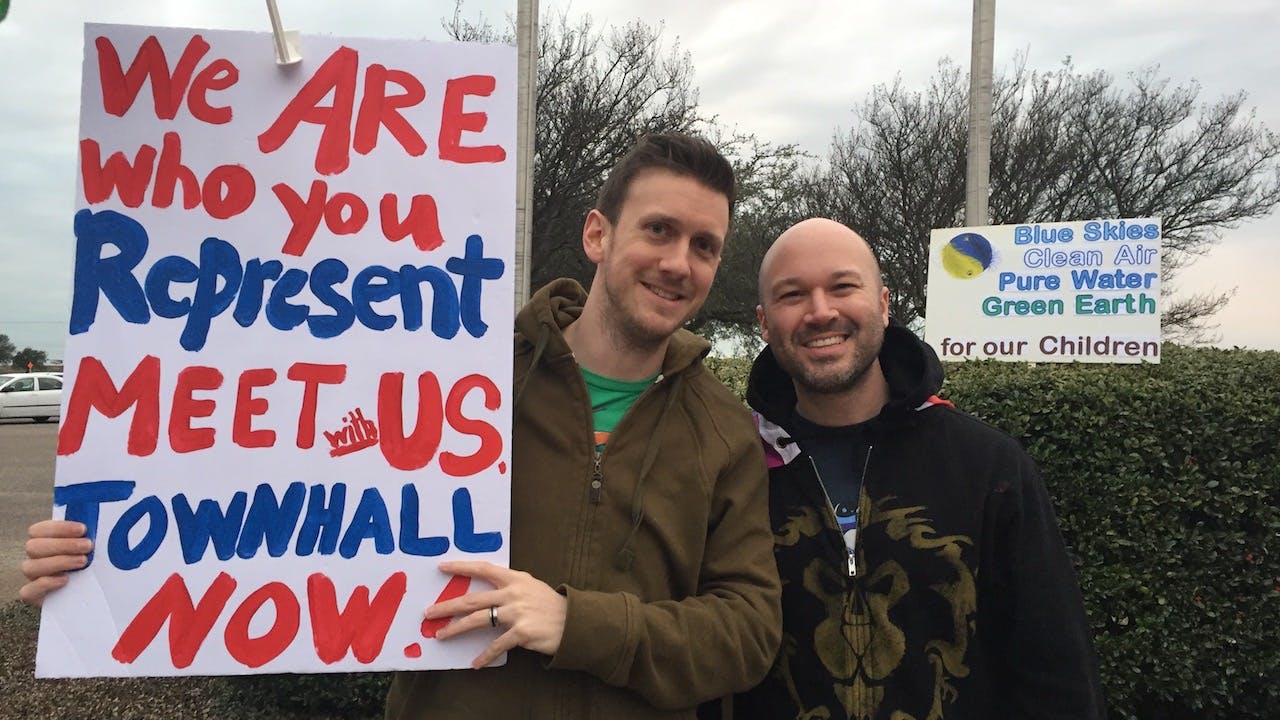

John Simpson and Mark Leech had never participated in a protest before last month. In fact, the couple—who got married in Temple last June—wasn’t particularly political before the 2016 election. They became concerned, though, that there would be new challenges to their marriage as Donald Trump began issuing executive orders (there have been reports that the administration is drafting an order on religious freedom, which concerns Simpson and Leech). Simpson was also concerned about Trump’s appointed Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, the border wall, and the suggestion of new tariffs on Mexican imports. And so, together, they started making phone calls. A friend told Simpson to call his senators, but when he tried, he kept getting a busy signal. Then, when the couple learned that Texas U.S. Senator John Cornyn would be speaking at the Temple Chamber of Commerce on Friday, January 27—as the keynote speaker at the annual Salute to Business banquet—they decided to show up in person to voice their concerns.

They weren’t alone, either. They were joined by their neighbors in the community—the Bell County Democratic Party, an older man in a suit and tie with a sign that read “This Is What A Liberal Looks Like,” a retired National Guard member—and by dozens of people from Austin and Waco. All told, there were about seventy people waiting outside the Temple Convention Center that evening, starting around 4:30 in the evening and sticking around until seven, waiting for their Senator to arrive and chanting slogans like “What do we want? A town hall! When do we want it? Now!” and “Pick up your phone!”

The demonstration wasn’t made up of seasoned activists and full-time ax-grinders; there were college students in the crowd, but also retirees. “We’re the moderates,” the retired National Guard member explained. Simpson, who voted for Cornyn in 2014, said, “I didn’t know what to expect. This is my first protest.”

It wasn’t the first protest for Suzie and Windel Dickerson, but it had been a while. The couple, who drove down from Waco, met during the Vietnam War, but this was the first protest they had attended together. Suzie protested the war in Vietnam, against Nixon, and rallied for the Equal Rights Amendment in her youth, but by the eighties, she had settled in, and was content to stay home until the election of Donald Trump. “Everything’s wrong,” she said when asked what brought her back to the picket lines. Windel shared the sentiment, but was more specific—he was there, he said, specifically to urge Cornyn not to let Trump “muzzle” the Congressional Budget Office. “Without that, they’re just governing in the dark,” he said.

At the event in Temple, an organizer led chants throughout the evening and tried to keep spirits up as the night got colder. “If John Cornyn can’t come to Temple, Texas, without seeing us,” he said, “He can’t go anywhere.” And that’s true, to a point—Cornyn came to Temple, but the crowd never saw him. However he arrived at the building, he did so with little fanfare. If he went in through the front door, he managed to avoid his constituents outside. Cornyn’s office did not confirm or deny if the senator saw the protestors when contacted by Texas Monthly.

Six days later, on January 31, a group of 150 people gathered outside of Cornyn’s Austin office at noon, standing on the sidewalk and asking to be let up to the office to speak with staffers. A small group of five was admitted, and they requested that a staffer come down to the sidewalk to see the larger group. One did, but it was a brief visit. She stepped outside the front doors, assessed the crowd, and immediately turned left to go eat lunch.

Eventually, as the lunchtime crowd had dwindled, the Senator’s staff agreed to meet with the demonstrators in groups of five at a time. Julie Gilberg of Austin, who waited with her husband until three in the afternoon to visit the office, said that the staffer who eventually met with them asked her to schedule appointments in advance—which, she says, might be a challenge. “I don’t have much luck calling that office.”

Eventually, as the lunchtime crowd had dwindled, the Senator’s staff agreed to meet with the demonstrators in groups of five at a time. Julie Gilberg of Austin, who waited with her husband until three in the afternoon to visit the office, said that the staffer who eventually met with them asked her to schedule appointments in advance—which, she says, might be a challenge. “I don’t have much luck calling that office.”

That’s a subject that’s come up frequently since the election. KXAN ran a story last week with the headline “Want to contact a lawmaker? You might have trouble,” and Houstonia reported that “neither Houston nor Austin phone lines were in service for days” in Senator Ted Cruz’s office.

For the past eight years, regardless of the direction of Congress, liberals have had a bulwark in the veto power of the presidency. Protestors who have surfaced in the new administration have been looking to the last successful opposition movement that sprung up when a single party controlled both houses of Congress and the presidency: the tea party. In January, the New York Times wrote about the link between the current push toward activism among liberals and progressives and the tea party movement.

In August [2009], routine hometown events got unexpectedly rough for members of Congress. At a neighborhood event at Randalls, a grocery store in Austin, Tex., Congressman Lloyd Doggett came face to face with a group of “tea party patriots,” carrying signs that said “No Socialized Health Care.” In Austin — and in congressional districts across the country — the tea partyers chanted what became their battle cry: “Just say no!”

Their tactics weren’t fancy: They just showed up on their own home turf, and they just said no.

Few of the demonstrators in Temple or Austin specifically cited the tea party as an inspiration for their activism, but they seem to be learning the lessons that led that movement to succeed, based on their numbers and the fact that each demonstration, thus far, has been larger than the last.

The question that remains is what lesson officials like Cornyn, Ted Cruz, and representatives throughout Texas—especially high-ranking members like U.S. Representative Michael McCaul, whose Austin office saw nearly 80 demonstrators show up on February 1 to urge him to change his position on Trump’s immigration executive order—learn from the experiences of their Democratic counterparts eight years ago. Less than two years after the rise of the tea party, Democrats lost their supermajority in the Senate, and their majority in the House. Cornyn isn’t up for re-election until 2020, but Ted Cruz could face a general election challenger in 2018. A representative like McCaul, whose district went from voting for Romney by a 20.3 point margin to voting for Trump by a 8.9 point margin, meanwhile, could be genuinely vulnerable if the momentum of the past few weeks is sustained and he fails to win over his newly-engaged constituents. (In McCaul’s own race against perennial candidate Tawana Cadien, where he raised $1.6 million in campaign contributions, he gained 20,000 voters over his 2012 number, while Cadien—who raised $3,531—saw her own total grow by 25,000 votes.)

How the officials receive the demonstrations is likely to have a big impact on how long they go on—and how large they end up being. A Cornyn aide issued a statement to Texas Monthly explaining that, if constituents are getting a busy signal when they call, it probably just means that right now there are a lot of people calling.

“Our office can receive as many as several thousand emails, phone calls, and messages a day. Like any phone system, when the U.S. Senate’s lines are tied up it can be harder to get through. A member of our legislative staff reviews every opinion expressed in a phone call, voicemail, letter, or email and responds to all written opinions individually as fast as they can,” the statement read, and for those who show up outside of the office looking for a meeting, “All of our offices try to see everyone who comes to visit, but there are space constraints.” (The statement concluded with screenshots of several social media messages from people praising the Senator and his staff for their communication.)

For McCaul’s office, responsiveness seems like a priority. Elizabeth Litzow, communications director for the congressman, acknowledged the demonstrations and the increased number of calls, saying, “The chairman continues to support the first amendment right of all Americans to peaceably assemble, so we are there to listen to what they have to say. With the one that happened in Austin, we had a couple staffers there to listen, because the boss was [in Washington, D.C.] voting. We recorded it so the boss could see it, and they were pleased with that, since they just wanted to have their voices heard. We took it back to the congressman, and now we have it in our database.”

It remains to be seen how many callers and demonstrators McCaul, Cornyn, Cruz, and other representatives in Texas will be adding to their databases. At least some of the people who’ve been drawn to activism in recent weeks, it’s clear, are finding standing on the sidewalk outside of their elected official’s office to be a worthwhile way to spend their lunch hour. The first-time activists in Temple and the reawakened protesters in Waco won’t be on their own if they decide to make protest and activism a part of their regular routine. “I’m planning on showing up next Tuesday,” Gilberg said.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- John Cornyn