Molly Ivins, Texas’ most famous resident journalist, pulls on a cigarette, shoves an errant strand of strawberry blond hair out of her eyes, stares down the mountains of notes and messages blanketing the surface of her rolltop desk, blinks twice through her glasses, stabs the play button on her answering machine, and states her goal for the day, and perhaps, the rest of her life. “What we try to avoid,” she says in a smoky voice that snags each and every syllable, “is that help-I’m-drowning feeling.”

What Ivins is drowning in, of course, is her own success. Her best-selling book, Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?, has propelled her out of her modest regional stature as a political columnist and the last remaining voice of old-time Texas liberalism into nationwide stardom. Suddenly she finds herself getting that A-list everyone-wants-you rush that comes with being (a) the nation’s favorite professional Texan, (b) a political pundit-humorist appearing on national newscasts, including 60 Minutes and Nightline, (c) a widely read author and two-time Pulitzer nominee, and (d) a 48-year-old woman reaping fame and fortune for the first time. But if something is getting lost along the way—such as the definitive book about Texas politics that she has always wanted to write—well, Ivins may be the only one who cares. She is, like so many Texas liberals of the old school, not entirely comfortable with attention and acclaim.

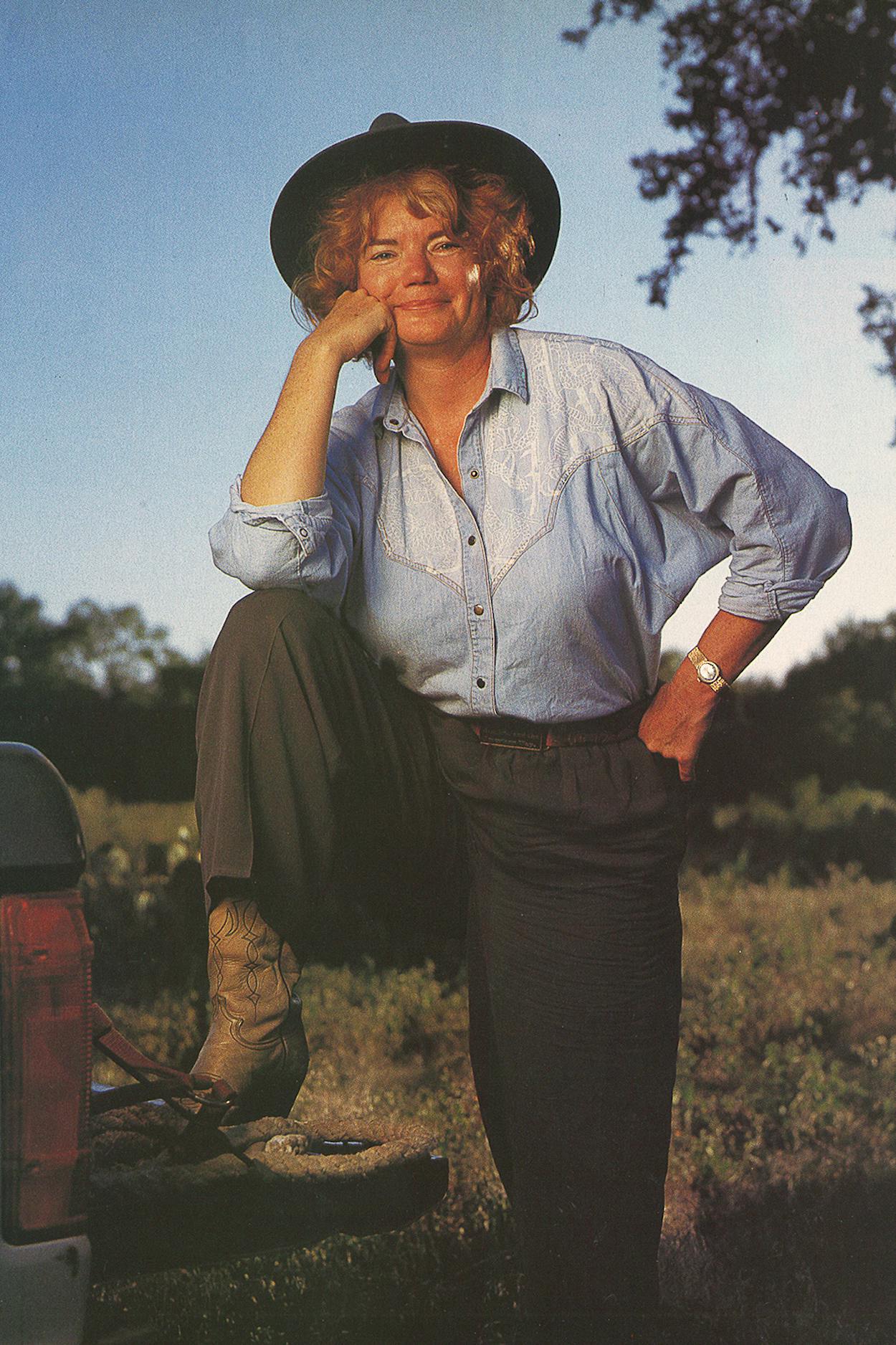

Ivins copes by cloaking her fairly formidable six-foot frame in the informality for which she has become infamous: bare feet, bare face, purple cotton shorts and a matching purple T-shirt. She is never without her most critical accessory, a smoldering Marlboro Light. She snatches serenity in measured steps, padding through her sunlit home in politically correct South Austin, tracing a path from the work littered dining room table to the sunny kitchen, where she lights another cigarette off the burner, puffs, and then heads back to the desk to check, once more, the appointment book that is already filling up with writing assignments and speaking engagements, coast to coast, through much of next year and beyond. Mostly, Ivins keeps at it, trying to ignore the anxious internal whisper that at times suggests that she does not deserve it all, that hisses that she is in grave danger of becoming one of those self-aggrandizing, self-important souls she has spent more than two decades satirizing. “I saw a shrink because I thought I suffered from fear of success,” Ivins confides grimly, “but I found out I suffered from fear of becoming an asshole.”

So, in essence, everyone wants Molly—except, perhaps, Molly. The unexpected blockbuster status of Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?—a collection of columns satirizing George Bush, Ronald Reagan, and the Texas Legislature, among others—raises those nagging fears that her impact as a journalist has been eclipsed by her impact as an entertainer. But what can you do when the national media keep calling?

In her column for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, which appears three days a week and is syndicated in 96 newspapers, Ivins explains politics and brings government to life. She may not be the country’s most trenchant analyst or its most dazzling reporter, but her unrelenting enthusiasm for human foolishness invites readers to take on the political process. “The most amazing, amusing and fascinating of games once again bursts upon us in all its insanity,” Ivins wrote at the beginning of the 1982 Texas legislative session. “The stakes they play for in politics are paper and money. The chips they play with are your life.”

She has, as the jacket of her book declares, “a sharp eye and a sharper pen.” She writes about stupidity in politics, and she never runs short of material. Her targets have ranged from pretentious yuppies (“In the New Age none of the vegetables are their regular color. It’s all red lettuce, yellow bell peppers, golden beets”) to the presidents of the United States (“Calling George Bush shallow is like calling a dwarf short”) and Ross Perot (“all hawk and no spit”). Yet she retains a tolerance for human weakness that sometimes borders on admiration. What other female journalist would have jokingly defended girl-crazy congressman Charlie Wilson of Lufkin by writing, “His standing order on secretaries is, ‘You can teach ’em to type, but you can’t teach ’em to grow tits’”?

And they love her—the politicians, the yuppies, the so-called conservative East Coast media elite. They can’t get enough. To meet the ever-growing demand for her work, Ivins begins with her column. Then she does short pieces for her favorite lefty journals—the Progressive, the Nation, and Mother Jones—and longer ones for mass-market publications such as McCall’s and Playboy. On top of that, she gets calls at least twice a day from radio shows, begging for her salty opinions. Ivins is also a frequent contributor to the MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour, National Public Radio’s All Things Considered and any other news show that suddenly finds itself in need of an authority on Texas. Finally, there are speeches; everyone from the American Civil Liberties Union to Republican clubwomen, it seems, wants to hear Ivins hold forth. “Do I want to speak to a bunch of women at the River Oaks Country Club?” Ivins asks herself, as she squints at her datebook. “No” she answers, moving on to the next request.

And so it goes, day in and day out, Molly schedules herself into mainstream America. You’d think she’d be happy. She’s famous. She’s almost rich. Texas finally had a governor from her side of the political spectrum, her old friend Ann Richards. The place that has supplanted Scholz Garten as the new Austin lefty hangout, La Zona Rosa, is even semi-air-conditioned. But in fact, Ivins is wary. Get her on the subject of success, and the West Texas marbles-in-the-mouth accent falls away, the one-liners dry up like a played-out well. “I have always been a left-winger and an outsider. I loved being that. I was perfectly cheerful with that role,” Ivins says. “Then suddenly you’re one of the talking heads on Nightline, and you think you must have sold out.”

Ivins takes another long drag on her cigarette, enveloping herself in that ever-present cloud of smoke. Behind it, the expression on her broad, open face is one part perplexed, one part mournful. No wisecrack, no punch line, follows. Because the truth is, for Molly Ivins, fame hasn’t been all that funny.

“I spend most of my life feeling like I’ve been shot out of a cannon,” Molly Ivins says, her long hair whipping wildly in the wind as a Yellow Cab hurtles across Houston toward her next destination. It is the third day of the Republican National Convention. Ivins, armed with three packs of Marlboro Lights, is dressed in a flowing turquoise ensemble and scuffed running shoes. She looks like a big butterfly in a big hurry.

Her schedule would exhaust weaker mortals. Today Ivins not only must write her syndicated column but she also has to gather information for assignments from the Nation and Newsweek. She will also fulfill her obligations as a pundit, hitting the talk show circuit, and of course, find material for her next column. It is a media star’s day, evenly divided between work and promotion.

Not a second goes to waste. By the time Ivins finishes breakfast at the Ritz-Carlton with the media elites from Newsweek, she has settled on a topic for her column: lying. “It used to be politicians were afraid to do it because they’d look dumb if they got caught,” Ivins remarks in the cab. In particular, she is amazed by the Bush camp’s distortion of Bill Clinton’s tax record and Hillary Clinton’s legal opinions. Dashing to the Star-Telegram’s makeshift office in the Astrohall, Ivins fortifies herself with coffee and cigarettes and starts her column. It is still unfinished when she grabs her purse, her notebook, and another cab for the ride to lunch at Brennan’s.

Barreling up Main Street, Ivins puts these free minutes to use. Inspired by Patrick Buchanan’s confoundingly divisive speech of the night before, which called for a house-to-house battle against decaying values, she tries out a line. “We missed the Renaissance, the Reformation,” Ivins declares, her unmade-up face brightening and her voice rising. “Now let’s have our own religious wars in this country!” Like comics and politicians, she is always either collecting lines or trying them out. Often, it’s hard to separate the real Molly from her shtick, conversation from rehearsal.

At the elegant, crowded restaurant, Ivins is feted by friends and ogled by the patrons. She floats her religious wars bit over the meal and is rewarded with another quip for her column. When a friend cracks, “Why should the Bosnians have all the fun?” Ivins swiftly appropriates it.

After lunch, Ivins races downtown to the Hyatt Regency, where she appears on NPR’s Talk of the Nation. The host is a balding, bearded man named Robert Siegel; the topic is humor at the convention. Ivins shares her guest duties with New York Times reporters Maureen Dowd and Frank Rich and comedian Al Franken, who is participating by phone. Ivins’ role, naturally, is to be a professional Texan.

“You are our native Texan here,” Siegel begins, “so I assume Houston strikes you as a reasonably normal place.” Ivins, who has made her name by making Texas a very abnormal place, knows what to do. Her syllables soften as she explains why convention delegates aren’t out jogging (“Republicans do not exercise in the public parks”) and jokes about Phil Gramm’s political alter ego, Dickie Flatt.

Siegel remarks that in Gramm’s keynote speech he had referred to “my mama” instead of just “mama,” which he understood to be improper southern usage. “It’s just ‘mama,’” Ivins concurs. “I wonder if the Republicans have to close up the mama gap.”

Maureen Dowd wants to know why so many Houston events have been decorated with baby elephant shrubbery: “Why do they have this topiary fetish?” Siegel wants to know about Lubbock: “What is it about Lubbock, by the way?” Finally, it is time for the inevitable question: On Ivins’ Top Ten List of Things Journalists Ask About Texas, this is number one. Dowd, at least, poses it ruefully: “Is George Bush a Texan?”

Ivins hunches toward the microphone and, like a sandwich chef at Sonny Bryan’s, starts to slather her words together. “Damn near everyone who died at the Alamo was from out of state,” Ivins admits, only it sounds like “Damn-near everwon whodahd atthealamo wuzfrum outtastyte.” Then she gives her stock response: “Real Texans do not use the word ‘summer’ as a verb. Real Texans do not wear those navy blue slacks with little green whales all over them And no real Texan has ever referred to trouble as ‘deep’”—long pause—“‘doo-doo.’”

Ivins does the show on automatic pilot, using lines she has used so many times before, validating the tired notions outsiders cling to about Texas. Not until she gets back in the cab does she let the professional Texan facade drop. “Bush hasn’t lived here for twenty-six years,” she says wearily. “The connection has become a little attenuated.”

Such is the price of being Molly Ivins—too much time spent on mindless pursuits and endless promotions. Her heroes are journalists like William Brann, the nineteenth-century Waco editor known as the Iconoclast, who was assassinated for his acerbic writings. But Ivins’ own great work remains unwritten. The year before last, she took a leave from her columnist’s job at the Dallas Times Herald to write what she christened The Big Book. It was conceived as a way to explain the effects of governmental actions on ordinary people—what happens, say, when a bill passes from the Texas Legislature into real life—and it would be told in Ivins’ sharp, irreverent style. But devoid of her daily deadline, Ivins foundered. Eventually she returned to the Times Herald, sporting a T-shirt that warned, “Don’t Ask About the Book.”

But the Herald proved to be no retreat. After lingering for years, the 112-year-old paper finally expired, and Ivins found herself on the unemployment line, accepting, as she says now, invitations from “everyone from the Marfa masons who wanted me to speak.”

At the same time, the project Ivins had christened The Little Book—otherwise known as Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?—was taking on a life of its own: It hit the New York Times best-seller list and dug in for 27 weeks. In other words, The Little Book was turning into A Very Big Book. Unfortunately, payment for The Little Book was contingent on some portion of The Big Book; hence Ivins found herself broke and out of work, even as she was making those requisite appearances on Leno and Letterman, denying rumors that she would replace Andy Rooney on 60 Minutes, and advising actress Judith Ivey on playing a Molly-inspired character on Designing Women.

The serious work would have to wait. The new job with the Star-Telegram and a renegotiated book deal—Ivins is now committed to doing a second collection of her pieces while she works on The Big Book—have erased her money problems. But fame and financial security have once again interrupted the ambitious project that might satisfy those inner demons and prove that Ivins is, indeed, the definitive voice of Texas.

Back at the Astro Dome, Ivins is wowing Jeremy Paxman of the British Broadcasting Company. She declares that “in absence of a flying pig,” the Republican nominee will be George Bush. She talks up Hillary Clinton, trots out Pat Buchanan’s speech (“Religious warfare, what an idea!”), and analyzes Bush’s chances for reelection. “Frankly, she says, “I think he’s dead meat.” This cracks up the Brits in the control room. “She’s very good, this woman,” they say to each other. “She’s fahntahstic!”

Ivins gallops back to the Astrohall to finish her column, then grabs another cab to meet with some editors at People, who are also charmed with her religious warfare line. Later, at the Star-Telegram pressroom, she downs a brownie for dinner and catches Marilyn Quayle’s speech on TV. When the camera pans on Quayle’s daughter, Corinne, Ivins deadpans, “Is she the one who has to have the baby?”

Then it’s off to another TV show—for ABC news, with humorist P.J. O’Rourke. As Ivins makes her way through the convention crowd, it is clear that everyone knows her. A security guard screams, “Molly Ivins, mah favorite columnist!” Other journalists, who have either worked with her or written about her, come up for a quick embrace: Los Angeles Times editor Shelby Coffey, the former editor of the Times Herald; Alexander Cockburn of the Nation; Calvin Trillin of the New Yorker; and Murray Kempton of Newsday (“I liked you when you were semi-successful!”).

The only event of the evening that completely commands Ivins’ attention is Barbara Bush’s speech. For this, she takes a seat in the press box adjacent to the stage. To her left she can see the First Lady on the podium; straight ahead she can see the surging crowd and an enormous TV screen aglow with shimmering white hair. Ivins straightens her spin as the steely Mrs. Bush dons her grandmotherly mask. She rolls her eyes when Midland is described as “a small, decent community.” But when Mrs. Bush hushes the floor with her symphony of selflessness and sacrifice, Ivins is galvanized. “However you define family, that’s how we define family values,” the First Lady tells the crowd. “For us, it’s putting your arms around each other and being there.” At the end of the speech, Ivins’ grin is as wide as a West Texas sky—and not because this unmarried, unruly liberal has bought a ticket on the family values train. “This is really an effective piece of political theater,” she declares. “Just ace.”

With eleven o’ clock approaching, Ivins hustles off to one more appointment. On the way, syndicated columnist Cal Thomas snags her arm. “Molly,” he asks smugly, “what Texas colloquialism do you have tonight?”

“Dead meat,” Ivins mutters and pushes past him, making her way to another show.

In a nail salon in northwest Austin, Molly Ivins is getting the second manicure of her life. The first one was for the Republican convention, and now, as she prepares to ride a campaign bus with Bill Clinton and Al Gore, she is treating herself again. The salon is located in a small converted home; the front room is full of girlish things, like makeup and sweatshirts decorated with ribbons and bows, and the back room is crowded with a baby swing and toys. A cheerful toddler appears and disappears. It is not an atmosphere one would normally associate with Ivins, who has come late to the world of femininity and domesticity. Part of Ivins’ shtick is her declaration, sometimes accompanied by batting lashes and rolling eyes, that she always felt excluded from “the norms of southern womanhood.” Indeed, she has lived most of her adult life as a nomad and a rebel, directed by her notebook, unfettered by convention. She did not plan her life this way. “In all my fantasies I always assumed I would get married and have six children along the way with the greatest of ease,” she says, splaying her nails so that the barely pink polish catches the light. At her twenty-fifth college reunion in the spring of 1991, Ivins confessed to her classmates that she was astonished at how they had planned their lives and met their goals. “I don’t think I’ve decided much in my life,” Ivins says now, bewilderment creeping into her voice. “Don’t you think life just happens?”

When Ivins talks about her childhood, her voice drops to a whisper and she becomes more terse than normal. The “sweethearts” and “darlin’s”—the southern girl’s social grease—disappear from her lexicon. As with the stories she tells on others, Ivins has been known to embellish the story she tells on herself, though she tends to leave out the jokes: The biography she fashions for readers and viewers can create the impression that she is a product of a tiny East Texas town, especially when the information is delivered in her best down-home patois. She also says that she was shaped by the racism of her era. A much-recounted memory is of being told that the water fountains designated for black people were dirty, while she could see even as a young child that the fountains for whites were the ones choked with chewing gum and litter.

While true enough, the stories Ivins has shaped for herself obscure a somewhat more complicated history. The East Texas of her childhood is actually the better neighborhoods of Houston, where her family moved from California after she was born. Her parents were from Illinois. Her mother was from a prominent family; her father, a proud and ambitious oil company executive, was not.

“A classically upwardly mobile family,” Ivins says dully. The Ivins’ home was prosperous—they moved to River Oaks when Molly was in the seventh grade—but it was also highly regimented and deeply conservative. Friends recall Molly’s father, James E., as a commanding figure who was hard of hearing as a result of a World War II injury. “He was kind of a Captain Ahab type,” an old friend remembers. “He yelled a lot, and you had to yell around him.”

Ivins, a bright student and a voracious reader, struggled to be heard in more ways than one. In the fifties and early sixties Houston was a segregated town, and the same hypocrisy Ivins saw on the street she also perceived at home. The family dinner table became the scene of screaming matches over civil rights between Ivins and her father, then general counsel for Tenneco. (Her older sister and younger brother, as well as her mother, were less political.) Ivins rarely won. “He was not the kind of guy you would identify with Molly,” says Roy Bode, an editor who worked with Ivins at the Times Herald. “He was the kind of guy you would identify as one of Molly’s targets.” Though father and daughter eventually called a mealtime truce, Ivins was marked. “I’ve always had trouble with male authority figures,” Ivins says, “because my father was such a martinet.”

Like many shrewd children, Ivins found other people who encouraged her worldview: a firebrand teacher at St. John’s, Houston’s most exclusive private school, who encouraged her writing talent and her budding liberal views; her best friend’s parents, social activists who subscribed to the Texas Observer, which was then literary and left-wing, the only publication of its kind for thousands of miles.

Another factor also moved Ivins from the mainstream: She was six feet tall by the sixth grade. At St. John’s she tried basketball without success and took up smoking, hoping it would stunt her growth. Her best friends were also bright but eccentric. “We weren’t cute; we weren’t in a sorority mold,” recalls one. “The only thing we had in common was that we just didn’t fit anywhere.” Dates were rarer than liberals, a fact Ivins took to heart. “If you’re a woman who’s never been picked, you’re able to take a different approach,” says the same friend. “You don’t have to be ladylike and prim.”

So at a time when many women, particularly in Ivins’ social strata, planned to stay close to home and join the Junior League, the tall girl from Texas set her sights on a career as a foreign correspondent. She studied philosophy and language at Smith College in Massachusetts, doing a little fine-tuning on her personality as well. “You try going to Smith from Texas after November 1963,” she says. “Being a Texan was not a treat. I learned to speak with no accent very quickly.” She took a year at the Institute for Political Science in Paris but soon after found herself back in Houston, reporting on sewers for the Chronicle. Ivins persevered, however, and won the Perle Mesta Franco-American Friendship Foundation Scholarship to the Columbia School of Journalism. She got her master’s degree, living on Campbell’s split pea soup with ham, and in the late sixties she got a job at the Minneapolis Tribune. She moved from the police beat to one she calls “movements for social change”—blacks, women, student radicals—but her heart was elsewhere. Ivins answered an ad in Ronnie Dugger’s Texas Observer, flew down to Austin for an interview, and was hired almost instantly. “Home,” she would come to say, “is where you understand the sons of bitches.”

“What people saw in the Observer was another way,” says Kaye Northcott, who was editor in 1970, when Ivins was hired to be co-editor. Often, the person who pointed the way was Molly Ivins. She had been teaching herself how to be an Observer writer—opinionated, funny, unabashedly left-wing—since her adolescence; now she turned her talents on a state that was as backward, poor, and ignorant as any Third World country. The first day Ivins set foot in the statehouse, she saw one legislator dig another in the ribs and announce, “Hey, boy, yew should see whut Ah found mahself last night! An she don’t talk, neither.” Ivins was hooked, not just on politics but on the theater of politics, and her great gift was that she could convey these comic but crucial scenes to her readers.

While other newspapers were mired in the House-Bill-x-passed-by-x-votes form of political reporting, Ivins was crisscrossing the state, packing a typewriter and one wrinkled, defeated dress, sleeping on air mattresses in the homes of Observer subscribers, reporting on the foibles of public servants. She brought home national issue of the day—racism, sex discrimination, abortion, busing, pollution. Almost always, her weapon was humor. On a case of rural air pollution, she stated, “Even hardly folk who enjoy the sharp, natural odor of a fresh cow pie find feedlots overpowering.” She described Governor Dolph Briscoe as having “all the charisma of bread pudding.” Morning News stories contained “the most meat-headed, shallow, unctuous, sanctimonious, vapid, ludicrous, knee-jerk prose ever printed in all seriousness by a major metropolitan daily.” In a sense, she would be heard. Using the Observer as her forum, Ivins promoted her “dripping-fangs liberalism.” She was for labor and against racism, for big government and against big corporations. She believed criminals could be rehabilitated and that gun control should be legislated. Above all, she believed in the sanctity of the First Amendment. If Daddy didn’t like it, lots of other folks did.

Ivins was having a great time. “Being a liberal meant having more fun than anybody else,” she says. Texas’ kamikazelike left held no power—“it was better to be right than win” is the way the left thought of itself—but these liberals were the state’s embattled intellectuals. For many, the futility of their enterprise funneled their sense of humor. Money didn’t matter; what counted were politics and beer, books and ideas, pranks and stories. Those were the days when a legendary crowd gathered at Scholz Garten, and under the stars and the live oak branches would flow twelve-beer arguments on the nature of man.

The Observer office, in an old house at Seventh and Nueces, was a rat’s nest of old newspapers, empty beer bottles, and overflowing ashtrays, but the people it attracted became the family Ivins should have had: Ann Richards and her husband, Dave, who practiced law from the first-floor office; writers like Gary Cartwright and Bud Shrake; good-time politicos like Don Kennard and Bob Armstrong; and humorist John Henry Faulk. Faulk, a garrulous activist and folklorist who had been blacklisted in the fifties, was a particular inspiration, teaching Ivins that she could be both a committed liberal and an entertainer. On the river trips and camp-outs, at the singalongs and great debates, the shy, self-deprecating writer perfected a new persona: thick-talking, quick-thinking, hard-drinking Molly Ivins. In Austin she could be an outsider, but she also belonged; for the first time in her life, she fit.

But only briefly. The New York Times had taken note of her work, asked her to write some op-ed pieces, and in 1976, hired her away. Friends believed she was bound for stardom. But the Times of that period was quite different from the paper it is now. In the mid- to late seventies it had few women reporters, few feature sections, and very little lively writing. For Ivins, that meant trouble.

She covered many of the big stories of the era and tried to imbue them with as much of her voice as the paper would allow. She covered the Son of Sam killings, Elvis’ funeral, and the state’s fiscal crisis. “Governor Carey proposed an $11.345 billion New York State budget today that calls for major cuts in welfare and Medicaid, along with a revised formula that would reduce local school aid to many districts” was a lead of one front-page story that ran under Ivins’ byline. In 1977 she was made Rocky Mountain bureau chief. From her home in Denver, she covered nine states, writing about, among other things, Mormons, Indian tribal courts, grasshopper plagues, ski bums, and the joys of Butte, Montana.

Her work was fresh and funny, but she was unhappy. “It’s hard to leave Texas behind,” Ivins says. “I carried it right with me.” She tried to style herself as the eccentric outsider—affecting her tall Texan act, wearing a buffalo-hide coat to cover the legislature in Albany, greeting everyone with “Hidy!” and taking her dog, Shit, to the newsroom—but it backfired. The Times did not want Molly to be Molly; they expected Molly to become, well, the Times. The copy desk regularly translated Ivinisms to Timesisms—converting “beer gut” to “protuberant abdomen,” for example—and the paper’s executives didn’t go for her laid-back Austin look. After her probationary period ended, Ivins was criticized not for her reporting but for dressing badly, laughing too loudly, and walking around the newsroom in bare feet. “That did bring back a whole lot of feelings,” Ivins says now. “‘I’m too big, I’m too loud, I’ll never fit in’—the way Texans are perceived in the East. I was just miserable.”

The situation deteriorated, and Ivins became more rebellious. After describing a ritual chicken slaughter as a “gang pluck,” she was called to the office of Abe Rosenthal, the paper’s legendary Napoleonic editor, and was demoted to number two on the city hall beat back in Manhattan. The painful episode exposed a conflict in Ivins’ nature: She wanted to be an outsider, but she also wanted to be a player. Expelled from the loop, she was sitting right back at her father’s dinner table all over again.

The Times Herald came to her rescue. In 1982 Dallas was still booming, and a real newspaper war was flourishing. The Herald had become a flashy paper of rogue columnists—John Bloom dreamed up drive-in-movie critic Joe Bob Briggs there. Ivins was recruited with the promise that she could write what she wanted; instantly, she resumed her traditional role, skewering the city’s white-male establishment. She called Ross Perot “a man with a mind half-an-inch wide” and Eddie Chiles “a loopy ignoramus.” Mayor Starke Taylor she nicknamed Bubba, Governor Bill Clements the Lip. She satirized Dallas’ passion for positive thinking: “The entire contents of one such rally,” she wrote, “is contained in the children’s book about the little train that thinks it can.” She regularly took aim at the city’s delirious devotion to conspicuous consumption: “The inequities in our society are becoming too glaring, too cruel, finally obscene. It is not just that the upper middle class hastens to switch to rice vinegar while children starve in Ethiopia—our fellow citizens are homeless in our streets.”

Eventually the city fathers stopped getting the joke, especially when her leads began with “It’s been ten years this month since Saul David Alinsky died” and “Happy May Day, comrades.” The bust was settling in. Pressure was put on the paper’s owner, the Times Mirror Corporation. It was felt, in the words of then editor Will Jarrett, that “Molly was not in love with Dallas and Dallas was not in love with her.”

In what appeared to be a brilliant compromise, Ivins was dispatched to Austin to cover Legislature once more. She was forty. She had learned form Saul Alinsky that a journalist should never want anything, but three years later, she bought a house—a real one, a nice one, with big windows and a garden. She began to plan—the idea for The Big Book was percolating—and the Herald would be her base from which she could come and go. But then the Herald was gone, and as had happened with so many plans before, this one seemed to slip from her grasp.

Driving back over the river toward that home in South Austin, Ivins is thoughtful. At the convention she had bemoaned the lack of role models for women. “With Hillary Clinton on one side and Barbara Bush on the other, you wind up thinking there’s something wrong with you,” she had told a reporter, adding, “I don’t think there’s a woman in America who doesn’t suffer doubt, confusion, and anxiety.” Today Ivins drops the pundit’s mask. She never married, she says, because the men she liked never asked. She is sorry that she never had a child. Her face, in the setting sun, is proud, but her voice is soft. For years she had something to prove to herself, and now maybe she doesn’t. She turns into her driveway and pulls out her keys, and out of ten polished fingers, only one is chipped.

Inside the cavernous art deco interior of the auditorium, Ivins is alone on a naked stage, behind a podium flanked by two small areca palms. She is dwarfed by the space. Something about the stripped-down scene—the hall blissfully unremodeled, the lone performer, the unreserved warmth of the crowd—gives this night at Lamar University-Port Arthur a timeless quality. Scenes like this one have played in Texas for decades: the sophisticate bringing to the smaller towns stories of the larger world.

As part of the university’s distinguished lecture series, Ivins is talking presidential politics, but the subject has been folded into her basic speech, the one that reveals how and what she thinks. Aglow in a bright purple dress, rhinestone earrings, and the adulation of the audience, she begins by spinning those seductive insider’s tales. She tells them what Perot sounds like when he calls to gripe about a column (“A Chihuahua,” she says, mimicking his high-pitched bark expertly) and what it was like to watch the campaign trail in 1984 (“Worst case of attempted milking by a presidential candidate I had ever seen”). She’s polished without being intimidating, and she’s got a seasoned comic’s timing. Guarded and sometimes haughty offstage, Ivins has the star’s gift of appearing open and intimate in front of a crowd.

When Ivins gets to Bill Clinton, the jokes taper off and her sermon begins. First she proffers an endorsement. “He likes to campaign and he likes to govern,” she says. She follows with an endorsement of the political process in general (“I still really believe in all of it”), followed by a recitation of the Declaration of Independence. “These are ideas people are dying for,” she tells the crowd. Turning somber, she warns, “We are in danger of taking our political legacy and flushing it away out of sheer inertia.”

Money is ruining our political system, Ivins declares, her voice quickening with intensity. “Sixty to seventy percent of the money that puts people in office comes from organized special interests,” she says. “This is legalized bribery.” Ivins exhorts the crowd to take back their government and to regain control over an “economy hijacked by ideological zealots in the 1980’s.” The after-dinner speech has become a call to arms, Ivins style. “It’s actually great fun to be a freedom fighter,” she tells the audience.

If it seems odd for a journalist to be endorsing candidates and freedom fighting, it pays to remember that Molly Ivins has never styled herself as an ordinary journalist. Her beat, as she sees it, is injustice, and objectivity is, to her, of only limited value. As her speech—and her column—reveals, Ivins knows what she thinks and how to package her ideas. “What I really want to do is get people interested,” she says. “They should be absorbed by politics as they are by sports. The best way to get them interested is to be funny.” The irony is that as Ivins’ fame has grown, it has become harder to accomplish her goals.

The most obvious example of this is Ivins’ professional Texan routine. “She’s singing for her supper,” says media critic John Katz, who hired Ivins at the Herald and remains a fan. True, Ivins can’t control which questions she is asked. Talk of the Nation was just one example of many; on C-SPAN an interviewer once asked Ivins whether there is a building in Texas in the shape of the state, whether Jim Hogg had a daughter named Ura, why so many Texas men have two initials for a first name, how Texas could possibly elect a woman governor, and of course, whether George Bush is a Texan.

Ivins has perfected stock answers to such questions, but geographical gridlock has set in. Although she privately admits that Texas has changed enormously in the twenty-odd years she has been covering it—“There’s been a real decline in the number of outrageous crooks and outrageous characters”—she hasn’t yet found a way to capture the place that is Texas now. The old Texas was a sorry joke for all thinking people, easy to parody. It was racist, poor, uneducated, and proud of it. The new Texas—multiethnic, two-party, more sophisticated, more ambivalent about its own myths—still has its problems but often deserves better, or fresher, material than Ivins offers. Her coverage of Dallas’ foibles was livelier, for instance, than her coverage of the Legislature is now. Perhaps the most disheartening example is the first essay in her book, which she calls “an attempt to explain Texas to non-Texans.” It was written in 1972: “The reason folks here eat grits is because they ain’t got no taste. . . . Art is paintings of bluebonnets and broncos, done on velvet. Music is mariachis, blues and country. . . . Texans do not talk like other Americans. They drawl, twang, or sound like the Frito Bandito, only not jolly. Shit is a three syllable word with a y in it.” It isn’t that contemporary Texans can’t laugh at themselves; it’s simply getting harder to see themselves in Ivins’ jokes.

Celebrity status has also converted Ivins from a reporter to an armchair columnist. Perhaps because she has spread herself so thin, she does little original reporting, choosing instead to draw her opinions from the reporting of others. (Colleagues note that she rarely appears on the House floor, and they were surprised to see her take a seat on the Clinton-Gore bus.) Whenever she actually goes somewhere—such as the political conventions—the freshness quotient of her column soars.

The other drawback to her armchair reporting is the opportunity for error. Little mistakes creep into the column with unfortunate regularity—Ivins wrote that the largest newspaper in Arkansas nicknamed Clinton Slick Willie, but it didn’t—as do an unfortunate number of corrections. (One August column contained two.) Ivins has also made her share of television bloopers, as when she declared on NBC that Jesse Jackson won the Texas primary during the 1988 presidential campaign (he didn’t) or when she told Jay Leno on the Tonight show that Texas House Speaker Gib Lewis had resigned (he hadn’t).

Finally, as Ivins’ fame as a liberal has grown, her worldview has not; she’s loyal to a fault to her side of the political spectrum. While other journalists of the left, notably at the New Republic and the Washington Monthly, have taken a second look at entitlements, regulations, and the limits of government in times of diminishing resources and conflicting needs, her bogeymen have remained constant. Corporations, bankers, and Republicans are still the villains in her columns. The Morning News is still “a right-wing newspaper.” Lloyd Bentsen gets no credit for his dogged work on health-services policy, while Ann Richards is rarely criticized. (It’s doubtful that a conservative politician would have received the kindness that Ivins bestowed on Lena Guerrero—an “excellent” railroad commissioner—in her column.) These days, Ivins is revealing less and preaching more. When pressed, she will admit that the left has been no more successful in tackling social problems than the right, but she lives for conflict, not complexity. “There’s something fun about being on the front lines,” she says of the Texas she sees. “It’s much easier in a place where the good guys wear white hats and the bad guys wear black hats and there are fewer shades of gray.” For Ivins, the fun is all in the fight; it is the fight, after all, that tells her who she is.

Back onstage, Ivins’ speech is drawing to a close. She has grown nostalgic. She tells a favorite funny story about John Henry Faulk battling censorship in South Austin, then warns again that we could lose our freedoms if we don’t fight to preserve them. She closes by quoting another old political warrior on his memories of battle: “‘Tell them how much fun it was.’” Her smile is blissful, her voice rich with passion and something like joy.

“You get out there and freedom fight,” she says to the expectant faces in the dark, “and you’re gonna have a glorious time.”

It is a Friday evening at La Zona Rosa. Instead of Scholz’s worn wooden floors, beer signs, and an oak shaded patio, this place is stage-set funky, with corrugated tin walls, ceiling fans, folk art, and south of the border hues. Good new music plays on the sound system, and the tables are filled with politicos, artistes, and a pair of young lesbians with matching bleach jobs, necking aggressively. Few people seem to be thinking about changing Texas, much less about the nature of man.

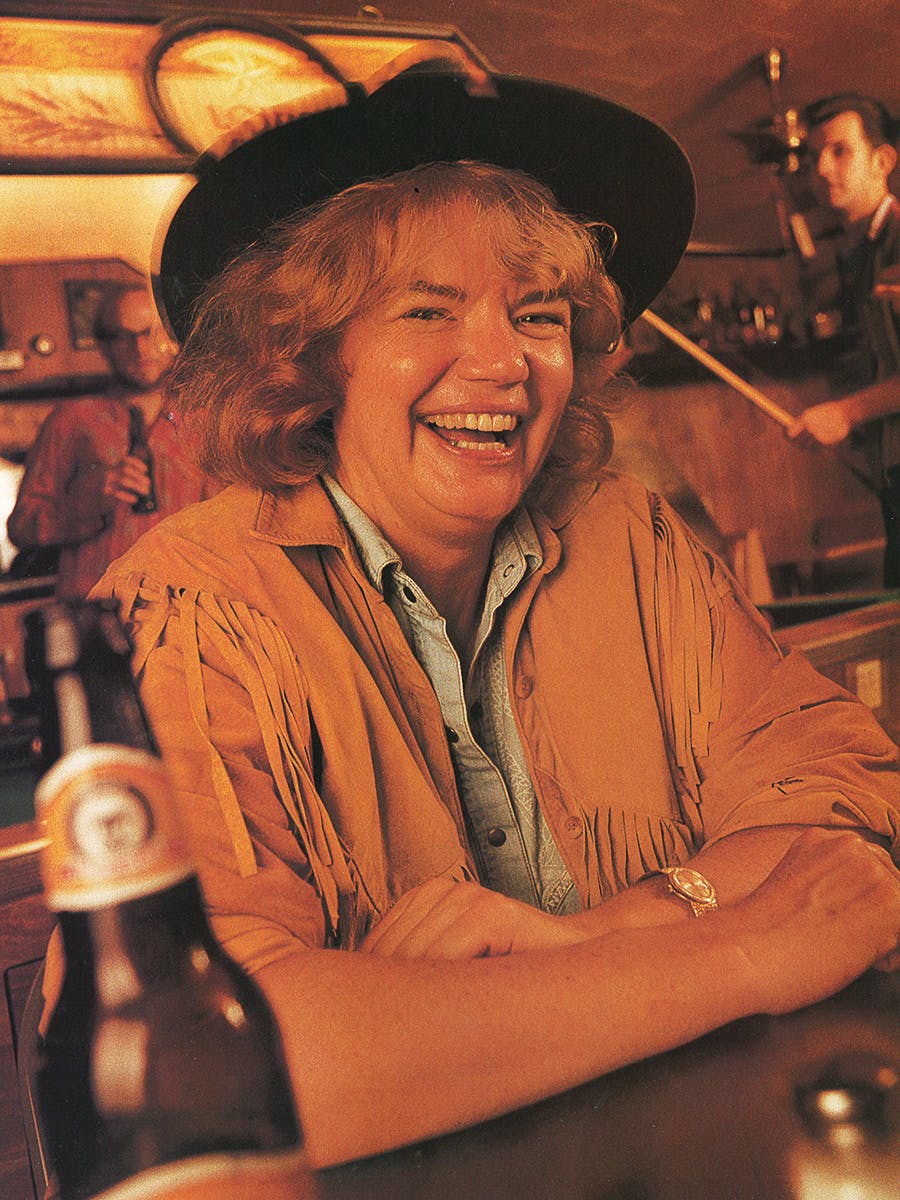

But along one wall, Molly Ivins holds court with a group of friends. They are mostly middle-aged guys, quick with a quip and loud with their laughter. As the shadows grow and the waitress pours refills, the table grows damp with water rings and dusty with cigarette ash, and the conversation rises and falls like the waves of a warm and friendly sea. Concessions have been made to the passing of time and youth, as the group complains about aches and pains, Austin traffic, and the efficiency of their liquid diets—the kind of talk that probably doesn’t figure much in conversations at Scholz’s. But soon they’re diving into James Baker’s role as Bush campaign guru (“How long is this guy bein’ paid by the taxpayers?” Ivins demands. “Is this an ethical question that would puzzle Gib Lewis?”); the Republicans in general (“It’s getting wiggy out there—did Barbara say she couldn’t imagine why anybody would sleep with George?”); and maneuvering in the ongoing morass that is congressional and legislative redistricting. “How fast does it move and what is the time frame?” Ivins asks of one plan. When a friend hints that a liberal victory may come to pass, Ivins clutches a fist, raises it, and laughs, and you believe for a moment that, for her, this is almost enough.

A few more Capitol groupies arrive, as do a couple of reporters, including Kaye Northcott, now with the Star-Telegram. Bob Slagle, the wizened, gum-chewing state Democratic party chairman, takes a seat at the opposite end of the table from Ivins, and she looks slightly abashed. “Shit,” Ivins grumbles. “I been crappin’ on him for years.” But as the voices grow louder and the smoke thickens, the good-natured ribbing at the table continues. Someone even teases Ivins about being introduced as a “talk show maven.” A rowdy consultant with unruly hair brings a baby in a carrier, plunks her down near Slagle, and then grabs a seat near Ivins to smoke. Ivins graces the baby with one long appraising look and then rejoins the guys.

The conversation floats to the left, as she complains she can’t find the right bumper sticker for her new pickup truck. “I liked one that says, ‘Visualize World Peace,’” Ivins says, “but I think I want one that says ‘Visualize Armed Revolution.’” Someone brings up Martin Wiginton, a much-beloved Austin lefty who died and chose to be buried in a pauper’s grave. It’s suggested that they take up a collection for a headstone inscription. Everyone eagerly agrees.

In the seconds that follow, you can sense a world slipping away, that ordered one where right and wrong were separate and distinct, where the battle lines were drawn and the boundaries clear, where wars were waged against enemies from without, not within. It was a world far, far from best-seller lists and talk show appearances; it was a world where it was easier to see what really mattered. For Molly Ivins, that world is gone. She has learned to claim her place in this one even as she mourns, like the most faithful lover, the loss of the old.

“I’ve made Kaye co-executor of my will,” Ivins confides. Then she pauses just a beat; the line has come to her, and a look of the devil lights her eyes. “I said, ‘Kaye, if there’s anything wrong with my head, pull the plug. Scatter my ashes in the Hill Country. Give my money to the ACLU.’”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- Molly Ivins