This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The out-of-towner who introduced himself as John Clifford sounded too good to be true—especially in early 1992, which was one of those down cycles that the aerospace industry has learned to expect in election years. Horizon Discovery Group, the small aerospace company operated by Neal and Karen Jackson, was struggling to stay afloat. So were most of the other small subcontractors who orbited the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. The Jacksons, who were expecting their third child in the fall, were about to lose their funding on a long-term project with one of NASA’s prime contractors, GE Government Services. They had talked about getting out of the business, maybe even leaving Houston. Then John Clifford phoned with a proposition that changed their lives and the lives of a lot of people at the Johnson Space Center.

Clifford talked with a Southern drawl and described himself as a good ol’ boy with more money than brains. He and his partner, Joe Carson, owned a number of companies, including Eastern Tech Manufacturing in Maryland and Southern Technologies Diversified in Atlanta. Eastern was developing a unique piece of hardware, and Clifford wanted the Jacksons to represent the product and put him in touch with the right people. The new hardware was a lithotripter, an ultrasound device that smashes kidney stones without invasive surgery. Clifford’s lithotripter was not the standard model found in hospitals, which is so large it has to be transported by an eighteen-wheeler, but a portable model small enough to fit in a spaceship. The hardware sounded right for NASA. In the weightlessness of space, calcium leaches from astronauts’ bones and forms spiny stones that cause immense pain. Clifford made it clear that he was talking about both government and commercial contracts—hundreds of millions of dollars—and that he was offering the Jacksons a chance to get in on the ground floor. He took note of Karen’s pregnancy and guaranteed that by the child’s first birthday the Jacksons would have made at least $1 million. Dazed by the offer, Neal and Karen made a down payment on a lot and hired an architect to design the $500,000 home they had always dreamed of owning.

The Jacksons were typical of the mom-and-pop entrepreneurs who lived in Clear Lake City and the other NASA bedroom communities south of Houston—a close-knit group of scientists, engineers, and business people, well-educated, ambitious, dedicated to the exploration of space. The older ones had arrived in Houston in the sixties, the dawn of America’s space program, but most had hitched their wagons to NASA in the seventies or eighties when they were still in school. Many had dreamed of being astronauts but had settled for positions as support troops. Neal Jackson had ten years of service as an Air Force pilot when McDonnell Douglas hired him in 1983 to train astronauts. Like others in the industry, Neal and Karen moved into a tidy middle-class neighborhood where names like Saturn, Gemini, Apollo, and Challenger seemed painted on every street sign, shopping center, park, or doughnut shop. From their patio gazebo they could look across a vacant field and see the sprawling, campuslike Johnson Space Center complex with the rocket casings of historic missions scattered about like the art of a post-utopian culture.

It was a homogeneous community. People belonged to the same trade organizations, clubs, and churches. They ate at the same steakhouses and drank at the same pubs. They perused the pages of Commerce Business Daily, a bulletin published every morning by the Department of Commerce listing every potential government contract from toilet paper to space shuttles, and swapped information on who was bidding what contract. Life in the aerospace industry revolved around NASA contracts. When a big-ticket contract was up for renewal, the community came to a rapid boil. Résumés were updated and mailed. People jockeyed for position. Small companies like Horizon networked and formed alliances, and large companies worked the halls of Congress. Eight or ten prime contractors dominated the process and set the agenda, subsidiaries of giants like Lockheed, Boeing, General Dynamics, Rockwell, Martin Marietta, McDonnell Douglas, and General Electric. When a contract moved to a new corporation, the scientists and engineers who had worked for the incumbent contractor simply switched badges and went to work for the company that had won the bid. Switching badges was not so much a sign of corporate disloyalty as it was the method by which NASA maintained continuity. In the end, everyone worked for NASA.

Karen founded Horizon Discovery Group in 1985 while Neal was serving with the Air Force Reserve. Later he became her first employee. She was still the company’s CEO in 1992, when the mysterious John Clifford came on the scene. In the argot of the industry Horizon was a body shop: The company sought support and service subcontracts in fields where it had some expertise—writing, for example, a womb-to-tomb mission requirement document for the space shuttle—then hired from the available pool of “bodies” the scientists, biomedical engineers, or market specialists a job might require.

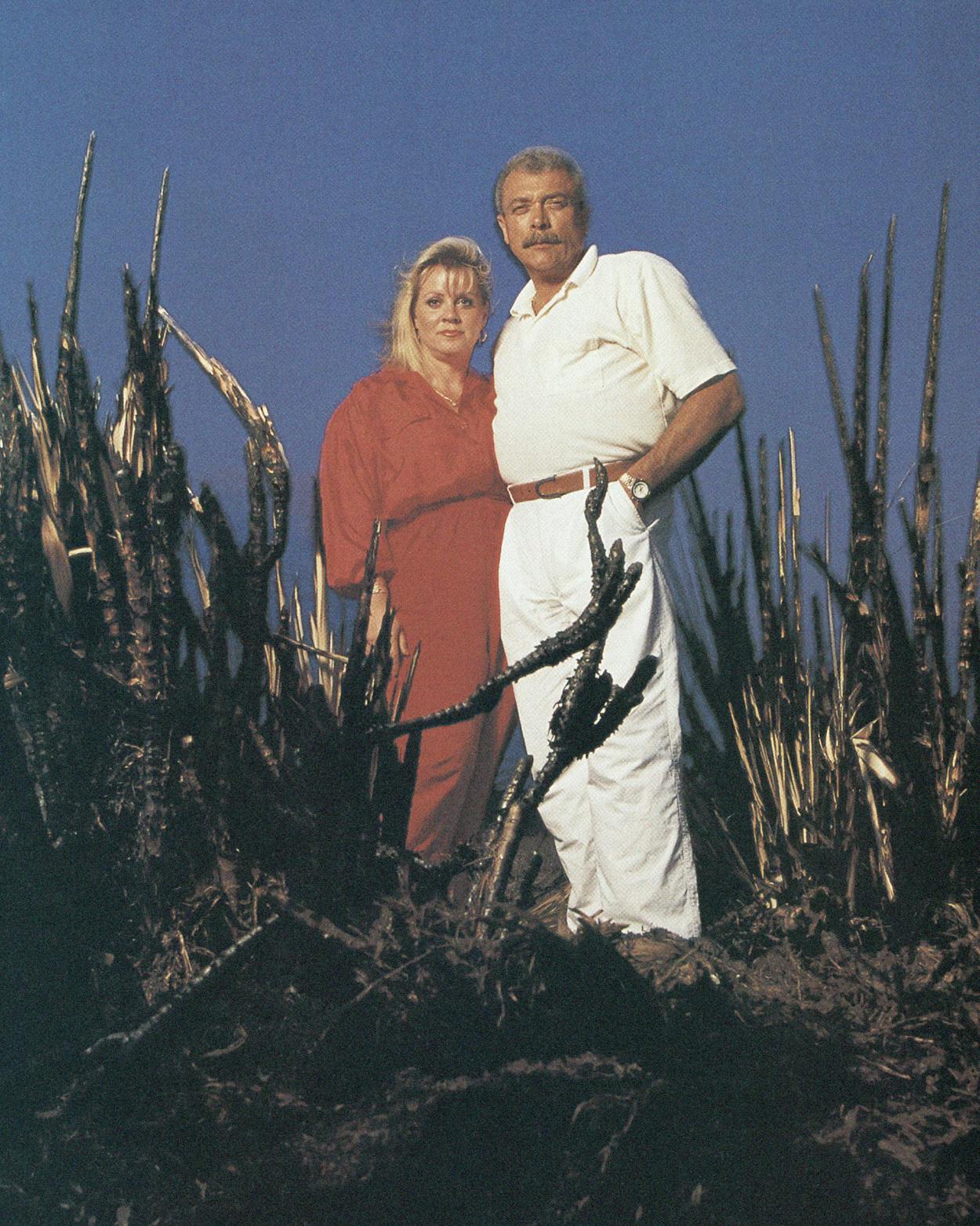

Blond, pretty, pleasingly plump, the 34-year-old Karen was a hardheaded businesswoman with little tolerance for nonperformers. She was Horizon’s organizational strength, the 43-year-old Neal its technical expert. He was a good front man, an aerospace engineer from Texas A&M, an Aggie’s Aggie, macho, egotistical, a bull of a man with broad shoulders, curly steel-gray hair, and fading good looks. He may have been prone to indecision and too slow with the follow-up, but his twenty years in the Air Force and the reserve and his background training pilots and astronauts made him a natural in the industry, as did his record as an unabashed patriot. When Operation Desert Storm erupted, Neal volunteered. Together, Karen and Neal gave Horizon credibility. You heard that word over and over in the aerospace industry. A company’s most precious asset was credibility, which was one reason John Clifford chose Horizon to represent the lithotripter. But there was another, more practical reason. Because Karen owned and operated the company, Horizon qualified as a “small, disadvantaged business.” Eight percent, or roughly $400 million, of the Johnson Space Center’s annual $5 billion budget was set aside for small, disadvantaged businesses.

On April 1, about a month after Clifford’s first telephone call, the Jacksons agreed on the deal at a meeting at Southern Technologies’ new office in a warehouse on Houston’s South Loop. Clifford wanted to seal the bargain with a handshake, but Karen insisted on a written contract. This was her first face-to-face meeting with Clifford. He was younger than she had expected, in his mid-thirties, and a little arrogant, something of a show-off. At that first meeting, Clifford went out of his way to impress on the Jacksons that he was a ruthless businessman who played by his own rules. If that bothered them, he said, now was the time to speak up. “Nice guys finish last,” he said. Karen volunteered that she’d been trying to tell Neal that for years.

This was Clifford’s proposition: Neal would guarantee his services as a contact man for the next twelve months, introducing Clifford and his company to the most important people in the community. Clifford mentioned in particular Carolyn Huntoon, the director of the Life Sciences Projects Division at the Johnson Space Center, who would have to approve the lithotripter project. In return, the Jacksons would be paid $7,500 a month for the first two months, then $10,000 a month for another ten months. In addition, they would receive 25 percent of any government contracts they brought in. This was a no-lose deal, a joint venture with NASA. Clifford emphasized that the deal with NASA was merely the seed money: The NASA logo could be invaluable in marketing the product commercially. After Clifford handed over the first payment that afternoon—in cash—Neal danced around the room and waved the bills in the air.

Driving back to Clear Lake that night, the Jacksons joked that they were probably being followed. “We’d never been paid in cash before,” Karen recalled. “It was legal tender for a legal contract, but still . . .” Things were moving faster than they had ever imagined.

The Setup

Of course they had never imagined that they were being set up. More than a year would pass before the Jacksons realized that they had been designated as the Judas goats of Operation Lightning Strike, an FBI sting designed to root out fraud and corruption among NASA employees and contractors. The wheeler-dealer who called himself John Clifford was really Special Agent Hal Francis, who had arrived in Houston the previous summer fresh from a similar sting in St. Louis called Operation Brown Bag. Francis was not all that different from the fictional Clifford, just a good ol’ country boy who grew up in Mississippi and cultivated a gift of gab. Karen Jackson’s initial impression was on the mark: Francis was a hot dog, ruthless in the pursuit of his own cause. Francis had served with the supersecret National Security Agency in the early eighties and joined the FBI in 1988. His reassignment to the Southern District of Texas in 1991 was fortuitous. The NASA Inspector General’s Office needed help. It had investigated hundreds of complaints of contract abuses and kickbacks, many of them at the space center, but had yet to get a single conviction. Most of the complaints came from anonymous calls to the NASA hotline.

Sifting through the open cases, Francis and his boss, Art Schultz, the supervisor of the government’s fraud squad—together with investigators from other federal agencies—created the elements of Lightning Strike. Francis would reprise his role as Clifford. A phony company, Southern Technologies Diversified, was created and given a financial history. When the Jacksons checked the company’s financial rating, it showed that Southern Technologies had annual sales of about $45 million.

Over drinks at Fuzzy’s, a downtown bar, the agents decided they needed something to sell, some kind of “black hole project” that would appear to suck government money into the tunnel of no accountability while actually sucking greedy contractors into the trap. Francis came up with the idea for the miniature lithotripter. As a prop, the bureau purchased a 1983 model ultrasonic device from Johns Hopkins Medical Center for $5,000. The company that supposedly manufactured the lithotripter, Eastern Tech, was a real company: Its president had cooperated in Brown Bag.

Once covert operations were approved in December 1991, Francis went undercover. All conversations with targets were recorded. In keeping with policy, Francis regularly filed reports and placed his tapes into evidence, and he met each morning with Art Schultz. The two met weekly with Assistant U.S. Attorney Abe Martinez and other federal prosecutors. To target a subject, the government has to establish that the subject is predisposed to commit a criminal act. Higher-ups at the FBI’s headquarters made the call on who was and wasn’t predisposed, but Martinez had to decide when a target had sufficiently compromised himself to warrant prosecution.

Francis’ initial targets were GE Government Services and the Life Sciences Division at the Johnson Space Center. He didn’t contact the Jacksons until he had spent all of January and most of February having doors slammed in his face. Frustrated by an inability to crack the close-knit community or score with the corporate executives and NASA bigwigs, Francis apparently decided to use Neal Jackson as bait. Once Jackson was under his spell, Francis began to construct a house of cards based on the belief that Jackson was predisposed to crime. This predisposition rested on two anonymous complaints: that Karen was merely a front for their small disadvantaged business and Neal was the real boss, and that Neal had once attempted to influence government contracts by flying GE Government Services executives on hunting trips to West Texas. Neither complaint survives scrutiny, but that didn’t stop the FBI.

Neal was the perfect instrument for Lightning Strike, a man so taken with his own abilities and ambitions that he would see what he wanted to see, hear what he wanted to hear. In the spring Jackson flew to Baltimore to inspect the manufacturing facilities at Eastern Tech. The plant specialized in “black box,” or top secret, electronics. Eastern had contracts with, among others, the National Security Agency, with whom Clifford claimed to have once served. Neal inspected areas where technicians were assembling circuit systems for robots, and he saw the prototype of the lithotripter. Neal had researched ultrasound equipment and believed the device to be genuine.

A few weeks later Neal and Karen flew to Atlanta to Southern Technologies’ headquarters. Clifford and Joe Carson (a fake name used by another undercover agent) met them in a Rolls-Royce convertible and treated them like visiting royalty. At NationsBank they watched Clifford sign a $1 million line of credit for the lithotripter. Always the Southern gentleman, Clifford hurried ahead to open doors for Karen. As they were about to leave, Karen gave Clifford a hug and for an instant felt him freeze. Months later she realized that he had been wearing a body mike.

Twice in the spring and summer of 1992, Clifford invited Neal to the Florida Keys for one of his boys-only fishing trips aboard his 54-foot cabin cruiser. There is a classic photograph, taken by Clifford, of Neal kissing a thirty-pound dolphin fish. The boat was one of the undercover agent’s favorite toys, a method of making targets relax and lulling them into compromising conversations. These trips usually included dinner at a fancy restaurant and an evening at a topless bar, another of Agent Francis’ passions. Clifford would knock down tumblers of whiskey and expound on his philosophy of ruthlessness, how he’d steamroll anyone who got in his goddam way. He talked about accounts in offshore banks and offered to arrange one for Neal that even Karen wouldn’t know about. Neal declined.

One night at a Fort Lauderdale bar, Clifford remarked that he didn’t care if the lithotripter worked or not. His only concern was getting money out of NASA. This statement pushed Neal’s button. His own tongue loosened by whiskey, Neal told Clifford to produce or get lost. “John, we don’t enter these things lightly,” Jackson said. “I’ll tell you, you can take your money and your three-day boat trip and shove it up your ass.” When Neal thought about Clifford’s cavalier attitude in the sober light of day, how he went out of his way to make even the most innocuous transaction appear sleazy, he decided it had something to do with Clifford’s background as a National Security Agency spook.

All that spring, Jackson introduced Clifford to the right people. From the perspective of the undercover agent, the right people were people who could be targeted. Meetings or lunches were arranged with individuals and groups at NASA and with major contractors. On three separate occasions, meetings were scheduled with Carolyn Huntoon, the space center’s director of Life Sciences, but all were canceled for various reasons. At a division of Krug Industries, Neal introduced his boss to 49-year-old Jim Verlander, a fellow Aggie and a business acquaintance. A research scientist, Verlander had been with NASA since the Apollo program and was currently working on an ultrasound device for the space station. This alone made Verlander a potential target. But there was something else that made the scientist ripe for exploitation—his vulnerability. Verlander’s pregnant wife suffered from cervical cancer, and the family had exhausted its savings.

Clifford showed Verlander a brochure on the lithotripter. Verlander told Clifford to forget it, that the machine was not on NASA’s wish list. On the other hand, if this technology could be redesigned as a multitissue imaging system that could study all the organs of the body, Verlander believed that it might sell. No problem, Clifford told him, the boys at Eastern Tech would get to work on it right away.

Clifford paid Verlander $5,000 to write an unsolicited proposal to the space center, extolling the wonders of the lithotripter—now referred to as a multitissue ultrasound imaging system, or MTIUS—and asking NASA to approve $600,000 to develop the prototype. This was a relatively small amount for NASA; Huntoon had the authority to approve it out of discretionary funds. Even so, getting the proposal into Huntoon’s hands would be tricky without inside help. A few days later Verlander called Clifford, offering to provide exactly that help. Verlander told Clifford that he had a mole deep inside NASA, close to Huntoon, who could tell Clifford how to get the project funded. This service would cost $3,000. Clifford agreed.

Though it now appears that there was no mole—Verlander invented the mysterious insider to improve his stock with Clifford—he did have a friend who worked in Huntoon’s division. David Proctor, a 33-year-old, pudgy, mild-mannered biomedical engineer who had once played saxophone in the Abilene Cooper High School band and had a graduate degree from Texas Tech, had been at NASA since 1988. Along with other engineers, Proctor had traveled to Russia with Huntoon to work on the joint U.S.-Russian space station, but he wasn’t tight with the director of Life Sciences. Proctor planned to quit NASA at the first opportunity and open a consulting firm with Verlander. The lithotripter could be their ticket to better things.

Though he never met Clifford, Proctor became Verlander’s partner, editing the proposal, supplying costs for hiring engineers, sharing the money. To fine tune the proposal and do future work for Clifford, Proctor needed a more powerful computer than the one he had at home (using his computer at the space center would have violated NASA policy). When Clifford learned of this dilemma, he loaned Proctor a $10,000 model through Verlander that was more than adequate for the job. A few months later Proctor was surprised to receive a $1,000 Christmas bonus from Clifford—again through Verlander.

In the weeks that followed, the undercover agent greatly accelerated activities. He persuaded the Jacksons to incorporate another small, disadvantaged business, Space Payloads and Commercial Enterprises, or Space, Inc., with Karen as its CEO. Space, Inc., was conceived as an electronics manufacturing company, though it would depend on Eastern Tech for hardware. The Jacksons owned 51 percent of Space, Inc., and Clifford owned the other 49 percent.

The first thing Space, Inc., needed to qualify as a vendor to NASA was a financial statement. Neal pointed out that the company had no finances, but Clifford didn’t see that as a problem. They would simply create one. After all, Eastern Tech, their partner, was well financed. Clifford offered to supply blank invoices or whatever else might help. They needed someone to draft the financial statement, and Neal thought of his friend Dale Brown, who was trying to persuade Clifford to sink money into one of his pet projects, a NASA theme park. Brown, 37, and two younger associates owned TerraSpace, a small company that shared offices with Horizon. These entrepreneurs saw themselves as “the future captains of the aerospace industry” and believed that the wave of the future was the transfer of technology from the government to the free market: NASA had blazed this trail repeatedly with such inventions as the cellular phone, and the lithotripter was following that same path. Assistant U.S. Attorney Abe Martinez later described Brown as “a gnat who wouldn’t go away,” but Hal Francis saw another target and put Brown on the payroll. Brown recalls that he used numbers supplied by Clifford to cobble together a financial statement good enough to satisfy NASA’s requirements. Clifford seemed pleased and promoted Brown to marketing director at a salary of $5,000 a month, plus 10 percent of the profits from the lithotripter.

In the summer and fall Clifford elevated the profile of the project and lured more victims into his net. He commissioned the prestigious Washington consulting firm of Beggs and Associates to lobby the lithotripter at NASA headquarters in Washington and in Congress. The president of the firm, Jim Beggs, had been the top guy at NASA during the Bush administration and had persuaded Congress to fund the U.S.-Russian space station. He had also been indicted on charges of falsifying government contracts, though the charges were later dismissed and the government issued a written apology. Nevertheless, the FBI and the Department of Justice believed that Beggs was dirty and gave Hal Francis permission to move on him.

But to give Lightning Strike real cachet, the FBI needed to snare an astronaut. Francis targeted two of them, one of whom turned out to be a friend and neighbor of Dale Brown’s. David Wolf, 36, was an expert on ultrasonic equipment and one of the inventors of a bioreactor that regenerates human tissue in three dimensions. More to the point, he worked directly with Life Sciences director Carolyn Huntoon. When Wolf learned of the miniature lithotripter from Dale Brown, he eagerly agreed to review it, and a dinner was planned with John Clifford and his partner, Joe Carson. The dinner developed into a drunken night on the town. In the company of Jackson and Brown, Clifford and Carson picked up the astronaut at his home in Clear Lake in a limousine. Drinks were poured on the way to the Rainbow Lodge in River Oaks. At dinner many bottles of champagne were consumed and a tab accumulated in the hundreds of dollars. Clifford waved off Wolf’s attempt to pay his part, but the astronaut persisted and left some money on the table. The second half of the evening evolved at Rick’s Cabaret, Houston’s premier topless club, where Clifford hired two dancers to put on a private show for his group. Long after the others were ready to leave, the undercover agent was still ordering drinks and paying the dancers.

They never got around to discussing the lithotripter. A few days later, on Clifford’s orders, Brown left a copy of the lithotripter proposal in Wolf’s mailbox. Brown should have known that the proposal was a proprietary document—a trade secret—and that any unauthorized person caught with it was committing a crime. Wolf said later that he threw it in the trash. Had he brought it to Carolyn Huntoon’s attention—as Clifford hoped—the act would have ended Wolf’s career as an astronaut and probably put him in jail. The undercover agent did not give up, however. On at least a dozen occasions in the months that followed, he tempted Wolf with offers of trips to the Florida Keys and other enticements. Each time, Wolf turned him down.

The FBI had deep pockets and Hal Francis knew how to use them. At the Space Expo Symposium at the South Shore Harbour Hotel in League City in October, giant corporations like IBM, Martin Marietta, and GE Government Services set up hospitality suites. So did little Space, Inc. With plenty of food, liquor, and sexy hostesses, Space, Inc.’s suite was perhaps the most popular at the symposium, attracting among others former astronaut Buzz Aldrin. At Christmas Karen planned a wine-and-cheese open house at the office, but Clifford decided instead to splurge for a black-tie affair at South Shore Harbour Country Club and invited the presidents and CEOs of all the top aerospace corporations. To speak to this group, the undercover agent hired former NASA administrator Jim Beggs, who chose a topic of interest to everyone, “NASA and the Clinton Era.” A month earlier Bill Clinton had been elected president. Many in the industry saw the 1992 election as a battle for the future of the Johnson Space Center, and Clinton’s victory almost assured that the center would endure. David Proctor recalled that his boss, Carolyn Huntoon, had boasted to her staff that if Clinton won, she’d be the new director of the space center. And so she was.

By the end of 1992, Karen was nearly out of the picture. Her baby, a third son the Jacksons named Colin, had been delivered by emergency cesarean section in September. Complications followed. In December the child almost died from a general seizure and spent two weeks at Hermann Hospital suffering from a rare neurological disorder. Clifford sent flowers and a card. Because the Jacksons had changed insurance companies after the child’s birth, the illness was determined to be “pre-existing” and hospital bills soon climbed above $100,000. On top of everything else, business was nonexistent. As the Jacksons became increasingly vulnerable, the FBI made its move. In October Clifford and Joe Carson told the Jacksons that the monthly payments of $10,000 would stop in November. In the future Neal would be paid according to the number of contacts he introduced. Neal didn’t understand what was happening, but Karen did: John Clifford was breaching their contract. She wanted to take the matter to their lawyer, but Neal persuaded her to wait. He still believed that by his baby’s first birthday, Clifford would come across with a million bucks.

The Trap

Early in January 1993, the Jacksons got a break, or so they thought. An executive for a Houston robotics manufacturing company, Automaker, called Neal about an item she had noticed in Commerce Business Daily. The Tobyhanna Army Depot in Pennsylvania was taking bids on an assembly robot. Perhaps her company and Neal’s company could bid it jointly: Automaker as the prime contractor, Space, Inc., as the subcontractor. At a meeting with the Automaker executive, Clifford boasted that he had a friend who had a friend at the Pentagon who could help land the Tobyhanna contract. Put off by his sleazy suggestion, the executive remarked that Automaker didn’t do business that way. “If you don’t bid it,” Clifford said casually, “we will.”

The Jacksons were flabbergasted. The notion of Space, Inc., as the prime contractor was ludicrous. But Clifford had it covered. Eastern Tech would buy existing hardware, modify it to Tobyhanna’s specifications, then step aside and allow Space, Inc., to be the prime contractor, thus giving the small company instant credibility. Clifford told Neal to write a proposal using numbers that Clifford would supply from “an inside source.” He reminded Neal that this was his final chance, that Space, Inc.’s future depended on getting the Tobyhanna contract.

After eleven months of frustration, the FBI was finally ready to spring its trap. In February Clifford brought news that the chief of procurement at Tobyhanna, Joe Umbriak (who had been recruited to go along with the sting), was coming to Houston and told Neal to take him out and “throw a couple of titty dancers in his lap.” A fax arrived from Umbriak informing Space, Inc., that the price it submitted was a little high, and Neal and Dale Brown suggested lowering it by $5,000. But Clifford vetoed that idea. “We’re basically buying the contract,” he said. “We don’t have to lower the price.” Later, he told Neal that his friend had slipped $5,000 to his man in the Pentagon. In private Clifford told Brown, “This is Neal’s last chance. If this does not come off . . . Joe [Carson] will cut Neal off at the knees.”

Clifford remained mysteriously out of town during the stroking of the procurement chief but nevertheless directed it with frequent telephone calls. On March 4 Clifford called Neal allegedly from Tallahassee, Florida, and told him that plans had changed. Umbriak wouldn’t be coming to Houston after all but wanted them instead to deliver some “entertainment money” to a gay friend of his who would be staying at the Hobby Hilton. In return, the friend would give them the bid price needed to win the contract. Neal was instructed to get together $400 or $500 in unmarked bills, seal them in an envelope, and deliver the envelope to the hotel room. After the conversation, Neal sat in his office for nearly half an hour, trying to sort out the mess he was in: payoffs at the Pentagon, insider information on a government contract, and now bribes to a homosexual. Neal made no secret of his homophobia. Handing over money to a homosexual was a sacrifice he could not make. Leaning on their longtime friendship, he got Brown to make the delivery.

A few days later, Clifford all but vanished as mysteriously as he had appeared a year earlier. Then, on August 2, Clifford phoned Neal unexpectedly and asked him to meet him at the warehouse. Driving north on I-45, Neal thought of the day he and Karen were returning home with $10,000 cash and the prickly feeling that they were being followed.

The warehouse was somehow different than Neal remembered. Walking into the foyer, he was met by a man he had not seen before, escorted to a small room, and told to wait. Neal saw giant blowups of photographs propped against a wall. One was a blowup of the cover sheet of the unsolicited proposal for the lithotripter. Another was the shot of Neal kissing the dolphin fish. There were other candid shots of Neal, all of them seemingly innocent and yet somehow sinister in this setting. A video machine with a TV monitor caught his attention and he realized he was watching a film of himself and Karen signing the contract with Clifford—there he was, dancing around the room like a fool, waving a fistful of cash at a camera he didn’t know was there, saying, “If the tapes are rolling, we’ll have to live with it!” Stacked nearby were boxes of audio and videotapes with his name on them. He lost track of how much time passed, then the door opened and four or five men with hard faces entered the room, some carrying pistols. Among them was John Clifford.

“My real name is Hal Francis,” he said, flashing his badge. “I’m a special agent for the FBI, and you’re in a whole lot of trouble.”

The Tally

Dozens of aerospace professionals fell for Hal Francis’ well-crafted performance, and those who fell hard enough ended up at the warehouse. Of all the bells and whistles that adorned Operation Lightning Strike, the warehouse treatment was the most exotic and diabolical, a brilliant exercise in coercive persuasion in which victims were systematically reduced to jelly. Although the traps were sprung over a number of weeks, all the defendants recalled a common experience. Once Agent Francis had introduced himself, other agents unveiled large white boards on which were printed in heavy black scrawl the “crimes” committed by the subject at hand. To one side was written the corresponding number of years in prison and fines. For example, Dale Brown had 21 felony charges against him totaling sixty years and $1.25 million. Another agent explained the options. The subject could leave, in which case he would be arrested in a manner calculated to best embarrass his family. Or he could stay and help himself. None of the Lightning Strike defendants had ever been arrested or ever imagined himself in such a predicament. Everyone elected to stay. Then they learned the ground rules. They could not contact an attorney, otherwise all deals were off. They couldn’t speak of what happened to anyone except their wives and ministers. Before their day was over, all except one had confessed to crimes so vague that they weren’t sure they were even involved. All of them had “flipped”—that is to say, they agreed to go undercover for the FBI and trap friends and associates. As a final act of submission, they were handed a telephone and instructed to call the next victim and lure him to this theater of hell. While the warehouse treatment may strike an average citizen as constitutionally dubious—uncomfortably similar to the North Korean method popularized in The Manchurian Candidate—the technique has been used for years by the FBI. Apparently it is as successful in this country as it is in North Korea.

Francis has said that from the start of their dealings, Jackson and all the other defendants knew that the lithotripter was a fraud. The government has released only a tiny portion of the thousands of hours of tape made during Lightning Strike. The available transcripts confirm that Francis-Clifford presented himself as a scumbag—a successful scumbag—and more than once he tells Neal Jackson and others that his primary concern is getting money from NASA, that he could care less if the equipment works. The Clifford character was a fountain of jabbering promises and mixed signals, but nowhere does he say the lithotripter is fake.

What is clear is that the undercover agent used all of his ample resources to establish himself as a legitimate businessman and that he manipulated his targets and led them “down the slippery slope of impropriety,” as Houston attorney Dick DeGuerin has described it. Francis worked for more than a year to manipulate Neal Jackson into committing a crime. At each stage, Clifford is the one who suggests the impropriety—paying in cash, hiding money in offshore accounts, creating a phony financial statement, trying to influence an astronaut to sneak their proposal through the back door, using insider information to gain contracts. His back to the wall, his career and family in jeopardy, Jackson finally agreed to pay a $500 bribe. Neal may have been weak, greedy, and not too bright, but if he is a criminal, it’s because the government enticed him to be one.

With Jackson in his back pocket, Clifford moved with relative ease. Seduced by the promise of huge profits from the lithotripter, the targets didn’t ask a lot of questions, and many bent over backward to please Clifford. For example, Verlander was enticed to write a proposal by the promise of 25 percent of lithotripter funding, and Verlander brought his pal David Proctor into the mix by lying that he had a mole planted deep inside Life Sciences. No telling how many people Clifford had in his sights: Art Schultz says the bureau eventually collected 40 to 50 prosecutable cases, though only 22 were turned over to the U.S. Attorney and 7 of those were rejected for insufficient evidence. A bitter debate ensued among various levels of bureaucrats over who should and should not be prosecuted.

Frequently the government’s requirement of predisposition came down to Jackson’s word to Clifford that a suspect was “our kind of guy.” Jim Beggs was targeted because Jackson remarked, “He knows how the game is played” and because another aerospace consultant (himself a target) confirmed that “Beggs and Associates knows how to spend your money without you winding up in jail.” The former NASA director escaped the trap, but his consulting partner, Jim Robertson, admitted accepting a proprietary document that, at the time the crime was allegedly committed, he had repeatedly told Clifford not to give him. An executive with Astro International fell for a similar trick. Clifford stuffed a brochure into the man’s pocket; folded inside was bidding information for a contract the company had already lost. The executive told me that he pleaded guilty, on the advice of his lawyer, to avoid being suspended from doing government business. Most of those who dared speak to an attorney were advised of the hopelessness of their positions. Vince Maleche, a division director at GE Government Services who pleaded guilty to accepting $2,500 from Clifford-Francis in return for placing Eastern Tech on a “short list” of bidders, was told by his lawyer that these were his options: He could live out his life on a half-acre plot in Alvin and maybe be found innocent or keep what he had and plead guilty. “The economics of pleading innocent were astronomical,” Maleche said.

Once the warehouse treatment began, they fell like dominoes. Maleche gave up his boss, Tony Verrengia, a retired Air Force officer who had joined NASA in 1964 and was one of the first men assigned to the space shuttle program. Verrengia gave up Carter Alexander, a pioneer of the manned space program who was the civilian equivalent of a general at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio and a few weeks from retirement after a distinguished 31-year career. Alexander, at the FBI’s direction, was helping to set up a slush fund to trap Carolyn Huntoon when Lightning Strike was leaked to the media. Though Huntoon was not a target during the covert operation, she became one after Proctor and Alexander flipped.

The truism that an honest man cannot be bribed was put to the supreme test by a relentless agent with an unlimited government expense account. Eventually, all the defendants succumbed to repeated temptations. They accepted cash for what appeared to be legitimate work and eventually turned over or accepted proprietary documents, at which point the cash became bribes. All of them did something that at least smacked of impropriety—including the corporations who allegedly accepted inside information. The $10,000 computer that David Proctor believed that he borrowed was viewed by the government as evidence that he took a bribe in return for using his influence to ram the lithotripter through NASA. This is ludicrous: Proctor was a peon in Life Sciences. But convincing a jury that he was not the mythical mole of which Verlander spoke so freely would have been difficult. Even though Proctor cooperated and did everything the FBI asked—including illegally entering a building and copying a credit card number—Proctor was one of only two defendants to get jail time. His real crime may have been talking to reporters for CBS. Ironically, long before Clifford showed up, Proctor was writing anonymous letters to the NASA inspector general reporting incidents of fraud and mismanagement and asking for an investigation.

Of the thirteen individuals who were ultimately fingered in Lightning Strike (two corporations were also nailed), Dale Brown was the only one who didn’t cop a plea. Brown’s rich uncle in New Jersey hired Dick DeGuerin, one of the few lawyers in Houston willing and able to challenge the sting. Once DeGuerin signed on, the government reduced the number of felony charges against Brown from 21 to 1, the only one they had any chance of proving—the $500 bribe to the man from Tobyhanna. DeGuerin’s defense was that his client had been entrapped. “If I show enticement on the part of the government,” the lawyer argued, “then the government has the burden of proving that Brown was willing to commit a similar crime before being enticed by the government. If the enticement is great enough, then predisposition is not a factor.” The judge didn’t buy that argument for summary judgment. An appeals court might have, but the point became moot when the jury deadlocked and a mistrial was declared. After interviewing the jurors, the government decided to drop the charge against Brown.

Lightning Strike accomplished several things, all of them negative. A brigade of federal agents worked 21 months and spent millions of dollars to trap such desperadoes as Jackson, Brown, and Proctor. Meanwhile, if there really were top-flight executives indulging in fraud and corruption, they are free to try again. The operation did prove that the space center had problems in its Life Sciences Division. The FBI was able to bypass the procurement system and run its lithotripter proposal through not once but three times. Carolyn Huntoon has said she rejected the proposal three times. In 1995 Huntoon lost her job as director of the space center; now she’s a NASA representative at the Office of Science and Technology in Washington, D.C. (Huntoon did not return phone calls requesting an interview.) Hal Francis resigned from the FBI, embittered by what he believes was a political decision to halt the sting prematurely. He now runs a private investigation agency in the Houston area and has written a book about Lightning Strike that has yet to attract a publisher. In the wake of the acrimony that developed between the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office over the sting, Abe Martinez requested a transfer from white-collar crimes to organized crime and narcotics.

Lightning Strike ended its covert phase in December 1993, a time when a major scandal could have seriously damaged the space center’s attempts to fund the U.S.-Russian space station. “Let me propose a scenario,” says Art Schultz, who retired from the FBI in 1995. “Let’s say a senator or a congressman who has put his political life on the line funding the space center hears that a major scandal is about to break. He calls up U.S. Attorney Gaynelle Jones and says, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ ” Schultz has no evidence that such a call was made. He’s merely relaying how he thinks it worked. Schultz says the U.S. Attorney’s Office lied to the FBI on several key issues, including a promise to prosecute two corporations. Instead, GE and Martin Marietta were allowed to pay a $1 million settlement without admitting guilt. “They bought their way out, plain and simple,” says the former head of the government fraud squad. “And they’ll just write it off to the next contract.”

Finally, Lightning Strike ruined the lives and careers of more than a dozen people and their families. Several defendants required psychiatric care, at least two contemplated suicide, and Dale Brown suffered a heart infection and had open-heart surgery. All feel betrayed by a government that they had served for years, and all have been barred from doing future government contract work. As confessed felons, they can’t vote or own firearms. All are on probation and many are under house arrest. Under the terms of their probation, the defendants can’t even talk to one another or compare notes.

Those who haven’t retired now labor at lesser jobs. Before Neal Jackson landed a job as a pilot for American International Airways, the Jacksons had lived for more than a year on their retirement fund and occasional flying jobs with the Air Force Reserve. Carter Alexander, who has a Ph.D. in physiology and was once a Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Air Force Academy, is a science teacher at Floresville High School. Brown is suing the government and all the corporations that cooperated with the government for $100 million. His partners at TerraSpace, who lost a $10 million contract because of Lightning Strike, are also suing.

In May, in defiance of their probation officers, a wretched group of Lightning Strike survivors met late one afternoon in the conference room at DeGuerin’s law office. This was the first time they had met face to face. One by one they stood and gave their names and a brief account of their ordeals. A few used the occasion to apologize to fellow aerospace professionals for ratting on them. All of them regretted that they had not demanded a jury trial. Having confessed to a crime, there is nothing to appeal. And yet the despair in their eyes was evidence that they understood the decision had been out of their hands from the beginning. “Once the FBI has you in their sights, you’re finished,” one of them observed, and the others nodded in agreement, almost before the words left his lips. “Even if you could beat the rap, you can’t beat the ride.”

Sting II

Even after the NASA probe, the FBI wasn’t through with Houston.

Recently, another FBI sting in Houston was launched to root out corruption at city hall. This time the bait wasn’t a phony ultrasound machine but contracts involving the city’s proposed $155 million convention hotel. Instead of rooting out corruption, however, this latest covert operation has resulted in charges of racism and entrapment and accelerated an already bitter behind-the-scenes turf war between federal law enforcement officials.

Zero Game

To date, the investigation of city hall has produced no arrests, no indictments, and a ton of confusion. The FBI claims that U.S. Attorney Gaynelle Griffin Jones refused to pursue the cases, and that in retaliation the bureau took them straight to the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. Jones disputes this and says that she took the cases to the DOJ. Washington responded by sending a special prosecutor to Houston to assist a grand jury in sorting out the mess.

Feds Run Wild

Some FBI agents believe that Jones, a Clinton appointee, sabotaged the sting to save Democratic officeholders. Jones’ supporters believe that the FBI’s old-boy network is conducting a vendetta against the U.S. Attorney, a powerful black woman with whom they have had a long-running philosophical quarrel. Bad blood between the two federal agencies goes back to at least 1991, when the FBI brought a case to the office of then U.S. Attorney Ron Wood involving a state senator accused of political extortion. “We had him dead, but they wouldn’t prosecute,” says Art Schultz, who at the time supervised the FBI’s government fraud squad. The feud ignited again during Lightning Strike.

Hispanic Outrage

Reaction to the sting has rocked Houston’s Hispanic community. Six of the eight black or Hispanic members of the city council were targeted, but not the five white members or the one Asian-American. Hispanic leaders fear that the sting has damaged their efforts to gain political respect, and suspect that the FBI preyed upon the Hispanic community’s cherished dream of having a place at the table. Betty Maldonado, a Hispanic activist appointed to the Port of Houston Authority by her patron, Mayor Bob Lanier, has been forced to resign because of the controversy. Maldonado was approached by undercover agents posing as wealthy Hispanic investors and hired to arrange meetings with minority council members. Maldonado says that what attracted her to the bogus investors was a promise that Hispanics would finally get an opportunity to be not mere subcontractors but investors in the hotel project. The sting became public when Maldonado refused to cooperate with the FBI and went instead to attorney Dick DeGuerin. Realizing that DeGuerin was about to expose the sting, FBI agents descended in the early morning hours on the homes of council members, grilling them for hours in an apparent effort to trap them in a lie. It is a crime to make a “material false statement” to any law enforcement investigator.

Final Irony

The sting has threatened the hotel project and prompted Lanier to ask Attorney General Janet Reno to intervene. Reno, by the way, is still looking into complaints from Lightning Strike.

G.C.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Houston