In November the citizens of the North Texas city of Denton went to the polls for the midterm elections. They filled in their ballots for the various political races—governor, senator, and so on—and then came upon a very curious proposition. They were asked to vote on an ordinance banning all fracking, a technique used in oil and gas drilling, within Denton’s city limits.

The proposition, one newspaper would later write, was “as odd as a vote against Friday night football.” Denton (population 130,000) sits on the northern edge of the Barnett Shale, the third-largest onshore natural gas field in the United States. Inside the city’s nearly one hundred square miles are more than 270 gas wells. They generate $1.1 million a year in taxes for city government and $2.4 million for the Denton Independent School District. At least ten thousand additional acres in Denton have already been leased by energy companies for future drilling, which guarantees the city more taxable bounty in the years to come.

For most of the past decade, all the wells drilled in Denton and the rest of the Barnett have been hydraulically fracked, a process in which pressurized water, sand, and chemicals are sent down the well bore to blast apart the shale and release its hydrocarbons. Fracking is the only economically feasible way to extract gas from the Barnett Shale. Even when oil and gas prices are soaring, conventional drilling doesn’t capture enough of the gas to be financially viable. So a fracking ban would essentially halt drilling in Denton.

Yet that was precisely what supporters of the proposition on the ballot were asking Denton citizens to do: eliminate within the city the very drilling technique that brings in so much money, not to mention the two thousand jobs it’s estimated to generate in the next decade. An organization called the Denton Drilling Awareness Group, started in 2010 by a home health care nurse named Cathy McMullen, had collected enough signatures from registered Denton voters to force the city council to put the issue on the ballot. The group claimed that residents who lived close to gas wells experienced higher rates of illness, due in part to the cocktail of chemicals that was sometimes vented into the air. What’s more, the group alleged, residents faced the constant threat of a large spill of toxic fracking fluids or even a well blowout. There was plenty of Barnett land outside the city limits for the oil and gas companies to exploit, McMullen and her group declared. Why bother Denton?

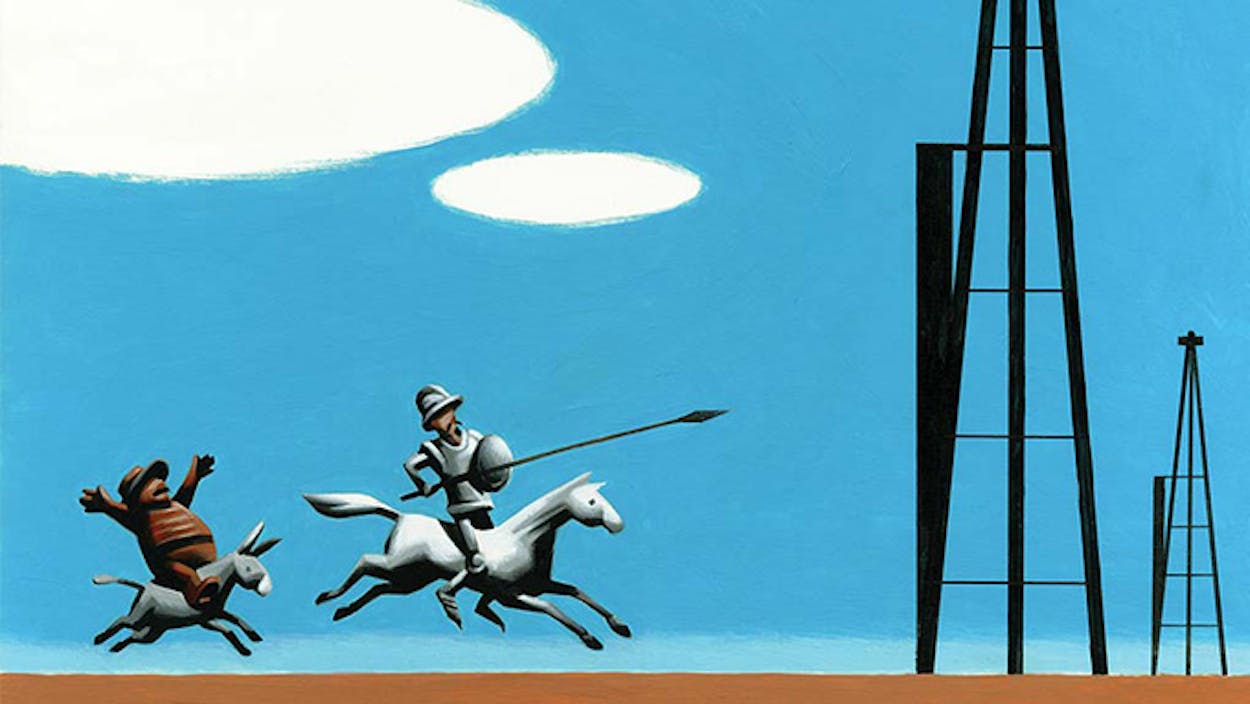

It seemed the most quixotic of grassroots movements, destined for defeat. McMullen and her group had raised only $75,000 to promote their campaign. The proposition’s opponents had raised $750,000, the vast majority of it from oil and gas companies such as Chevron, Occidental Petroleum, and XTO Energy. Spokesmen for the oil and gas industry dismissed the anti-frackers as nothing more than liberal “activists.” Surely, they added, the good voters of Denton would see through the activists’ “scare tactics,” “mischaracterizations of the truth,” and “anti-oil-and-gas ideology.”

But that wasn’t quite what happened. On election night, at a party at a small Denton nightclub, McMullen and her supporters stared at one another in disbelief as the results were announced. The proposition had passed 59 percent to 41 percent—close to a landslide. For the first time in Texas history, a municipality had banned fracking. “Denton has had enough of fracking!” McMullen cried. “We have had enough!”

McMullen, who is 56 years old, is hardly an activist. “I don’t know leftist from rightist,” she told me. She is married to a retired FBI agent whom she describes as “not exactly a radical man.” After spending many years in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, they moved in 2004 to a small farm in Wise County, west of Denton, where McMullen planned to raise miniature donkeys after she retired. They arrived just in time for the Barnett fracking boom. “A company started drilling in the property right next to ours,” she said. “We went from a peaceful country life to feeling like we were in an industrial zone. But there was nothing we could do. When you live in the country, you have no rights.”

In 2009 McMullen and her husband decided to move into a neighborhood on the west side of Denton. Within a week of arriving, McMullen saw that an oil company was preparing to drill a gas well about three hundred feet from their neighborhood park. She quickly learned that Denton, like a lot of municipalities, was not prepared for urban drilling. The city did have a setback ordinance on its books that prevented any drilling within five hundred feet of residences or parks—hardly much of a setback at all—but the ordinance allowed for numerous exceptions. For instance, it allowed operators to rework fracking sites that were permitted long before the setback provision was enacted.

McMullen recruited her husband and a few of her neighbors—among them, an opera singer, a librarian, a University of North Texas student, and a doctor—to help pass out flyers to Denton citizens about the dangers of fracking. Though no long-term study has been conducted of the adverse environmental or health effects of fracking—and the industry claims that allegations made by anti-fracking organizations are baseless—no one can deny that the life of a neighborhood is com-pletely disrupted when a gas well is drilled and fracked nearby. The noise from the drilling rig is screeching. Dust billows into the air, and the chemical odor is nauseating. Trucks barrel up and down roads. In the evenings, the light from the huge electric lamps illuminating the drilling site is nearly blinding.

McMullen and the Denton Drilling Awareness Group couldn’t halt the fracking near her local park—the city had allowed the drilling—but they continued pushing for stronger ordinances to keep oil and gas companies out of the city’s neighborhoods. Finally, in January 2013, after numerous hearings and delays, the city council passed regulations that prevented drilling within 1,200 feet of any residence. A few months later, an oil and gas company named EagleRidge Energy, claiming that the new restriction still didn’t apply to existing drilling sites, defiantly began fracking an old site within a few hundred feet of a neighborhood called Meadows of Hickory Creek. “It was close to where a school bus dropped off kids,” McMullen said. “Clouds of black emissions were pouring up from the drilling site. The kids got off the bus and ran for their homes, holding their noses. Their parents wouldn’t even let them go trick-or-treating at Halloween because the air was so bad.”

McMullen’s group decided its only recourse was a citywide referendum on the matter. The group quickly collected two thousand signatures, enough to place a referendum on the November 2014 ballot. Some of the signatures came from liberal students and faculty at the University of North Texas, located in the heart of Denton. “But what was amazing to me was how many of our supporters were just everyday citizens, from local merchants to Republican housewives to retirees who, deep down, were worried that their quality of life was in jeopardy,” McMullen said.

With little money for advertising, the anti-frackers resorted to door-to-door visits and small community rallies (one of which featured the Denton polka band Brave Combo). The pro-frackers—made up of the Denton Chamber of Commerce, the Denton County Republican Party, and Denton Taxpayers for a Strong Economy (a group started by two local businessmen, both of whom own land and mineral rights in the area)—barraged voters with mass mailings, billboards, and radio and television commercials. They warned that a ban on fracking was essentially a ban on all drilling and that Denton’s economy would never recover. Most voters just shook their heads and marked their ballots to stop the fracking.

The story, though, is hardly over. Since the election, both the Texas Oil and Gas Association and the state’s General Land Office have filed lawsuits against the city seeking a permanent injunction against the ban. In their pleadings, they claim the new ordinance is unconstitutional.

In particular, the lawsuits contend that state law gives two state agencies, the Texas Railroad Commission and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, exclusive jurisdiction to regulate the state’s oil and gas wells and that localities have absolutely no say in the matter. Christi Craddick, the Republican chair of the Railroad Commission, seemed flabbergasted that the people of Denton would dare infringe upon her territory, and she made clear in a post-election interview that fracking in Denton wouldn’t stop. “I’m the expert in oil and gas, and the city of Denton is not,” she told the Texas Tribune. “It’s my job to give [drilling] permits [to oil and gas companies], not Denton’s. . . . We’re going to continue permitting up there.”

Whatever happened to the once beloved notion of local control? When I asked Tom Phillips, the former chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court who is now a lawyer representing the Oil and Gas Association, why anyone should be all that upset if one city wants to ban fracking, he told me to read section 92.001 of the Texas Natural Resource Code, part of which states, “It is the intent of the legislature that the mineral resources of the state be fully and effectively exploited.” That means, Phillips explained, the state’s policy is the “sufficient recovery of natural resources.” He went on, “And that means a city has no authority at all to supersede state law and say, ‘There will not be any drilling for oil and gas in my backyard.’ That might be the way it works in other states, but not here.”

In other words, Denton, don’t mess with Texas’s oil and gas.

The city’s lawyers will defend the ordinance by arguing that localities have a constitutional right to protect the safety and welfare of their citizens, which means they get to regulate industries within their borders. They might go as far as to say that public health trumps property rights. But the chances of their winning those arguments in front of a conservative Texas court are about, well, zero.

What’s more, the oil and gas folks aren’t about to give other cities the chance to follow Denton’s lead and cut into their profit margins. (Rumors are circulating that groups in Mansfield, Arlington, and Alpine, in far West Texas, are planning their own anti-fracking petitions.) Oil and gas lobbyists are already pushing the Legislature to pass a bill expressly forbidding a municipality from banning fracking. Cities would presumably still be allowed to establish setbacks and such things as reasonable hours of operation at a drilling site, but they couldn’t abolish fracking. If the new legislation passes—and, let’s be honest, it very likely will—the fight will essentially be over.

As for Cathy McMullen, she still holds out some hope that the Denton ordinance might stand. But her greater hope is that her group’s little David-versus-Goliath campaign will not be forgotten—that, at the least, oil and gas companies will be more socially responsible. “We’re not tree huggers,” she said. “We don’t hate oil and gas. We just want some respect and some protection. Is that really too much to ask?”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Fracking