It was a brisk cloudless Halloween afternoon, the kind of autumn day that redeems six months of unsparing Texas summer: football weather. Inside Austin’s suburban Hilton Inn, Governor Dolph Briscoe had chosen the Tenth Annual Texas Conference on Tourist Development as the occasion for a rare public appearance. To a round of applause led by his wife, Janey, he saluted the state’s Coca-Cola bottlers, whom he awarded a Special Citation of Merit for their distinctive contribution to tourism: giving away a package of discount vacation coupons with every case of Cokes. There were other prizes, a speech, handshakes all around.

Outside, the Hilton’s marquee announced in foot-high letters:

NOW APPEARING

THE TOTAL STRANGERS

Another Briscoe anecdote was born.

The sign was not a prank, the Hilton’s management protested later with a hint of dudgeon: there really is a group called the Total Strangers, an easy-listening dance band performing nightly in the hotel’s pub. Just a coincidence.

But a provocative coincidence, nevertheless. Somewhere, no doubt, there are other officeholders as reclusive, as secretive as Dolph Briscoe—a comatose ward-captain in the Bronx, perhaps, or a furtive county clerk in the wilds of Idaho. But are there any equal in stature to the chief executive of the third largest state?

It was not supposed to be that way. Briscoe, after all, once sought the governorship on a promise to throw open his doors to the public every two weeks, so that “anyone who wants to complain, make suggestions, or just talk to the governor will be welcome.” Try that today. For all practical purposes the Invisible Man of South Texas is unique among the country’s leading political figures. His low profile, and the lengths he has gone to protect it, have made him an enigma to many and a joke to others.

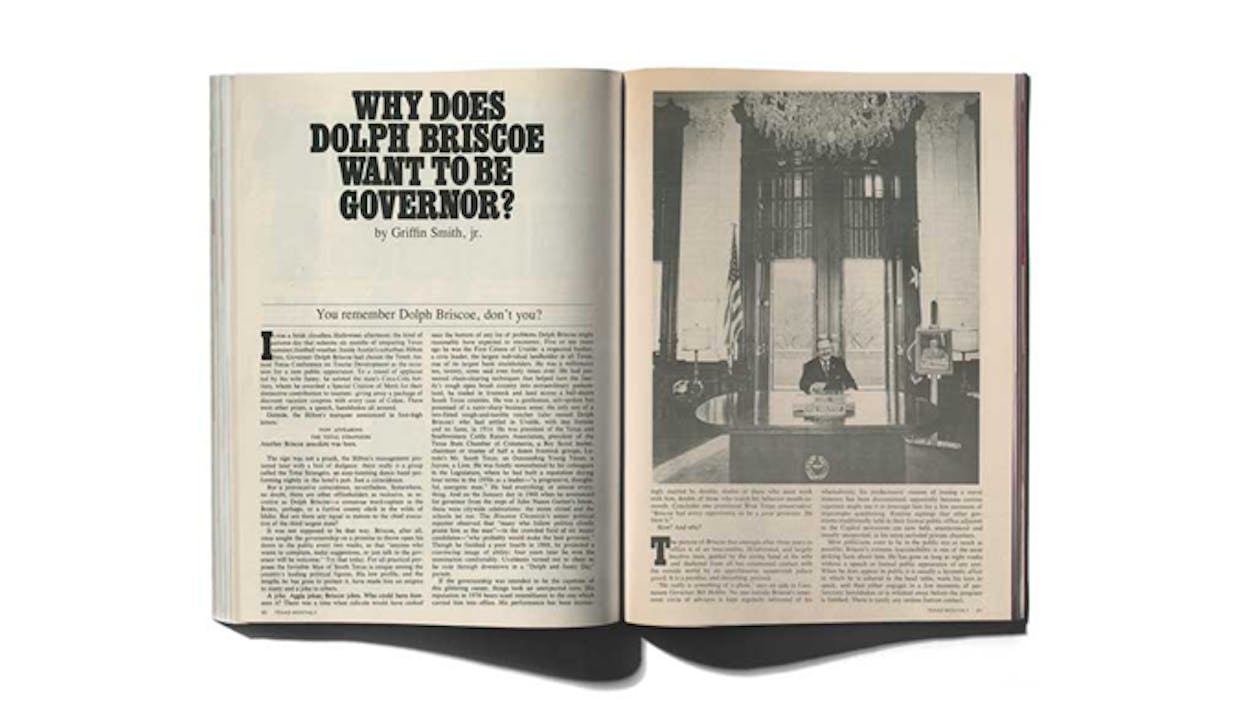

A joke. Aggie jokes. Briscoe jokes. Who could have foreseen it? There was a time when ridicule would have ranked near the bottom of any list of problems Dolph Briscoe might reasonably have expected to encounter. Five or ten years ago he was the First Citizen of Uvalde: a respected banker, a civic leader, the largest individual landholder in all Texas, one of its largest bank stockholders. He was a millionaire ten, twenty, some said even forty times over. He had pioneered chain-clearing techniques that helped turn the family’s rough open brush country into extraordinary pastureland; he traded in livestock and land across a half-dozen South Texas counties. He was a gentleman, soft-spoken but possessed of a razor-sharp business sense; the only son of a two-fisted rough-and-tumble rancher (also named Dolph Briscoe) who had settled in Uvalde, with less fortune and no fame, in 1914. He was president of the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, president of the Texas State Chamber of Commerce, a Boy Scout leader, chairman or trustee of half a dozen livestock groups, Laredo’s Mr. South Texas, an Outstanding Young Texan, a Jaycee, a Lion. He was fondly remembered by his colleagues in the Legislature, where he had built a reputation during four terms in the 1950s as a leader—“a progressive, thoughtful, energetic man.” He had everything, or almost everything. And on the January day in 1968 when he announced for governor from the steps of John Nance Garner’s house, there were citywide celebrations: the stores closed and the schools let out. The Houston Chronicle’s senior political reporter observed that “many who follow politics closely praise him as the man”—in the crowded field of six major candidates—“who probably would make the best governor.” Though he finished a poor fourth in 1968, he projected a convincing image of ability; four years later he won the nomination comfortably. Uvaldeans turned out to cheer as he rode through downtown in a “Dolph and Janey Day” parade.

If the governorship was intended to be the capstone of this glittering career, things took an unexpected turn. His reputation in 1976 bears scant resemblance to the one which carried him into office. His performance has been increasingly marred by doubts: doubts of those who must work with him, doubts of those who watch his behavior month-to-month. Concludes one prominent West Texas conservative: “Briscoe had every opportunity to be a great governor. He blew it.”

How? And why?

The picture of Briscoe that emerges after three years in office is of an inaccessible, ill-informed, and largely inactive man, guided by the strong hand of his wife and sheltered from all but ceremonial contact with the outside world by an apprehensive, amateurish palace guard. It is a peculiar, and disturbing, portrait.

“He really is something of a ghost,” says an aide to Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby. No one outside Briscoe’s innermost circle of advisers is kept regularly informed of his whereabouts; his predecessors’ custom of issuing a travel itinerary has been discontinued, apparently because curious reporters might use it to intercept him for a few moments of impromptu questioning. Routine signings that other governors traditionally held in their formal public office adjacent to the Capitol newsroom are now held, unannounced and usually unreported, in his more secluded private chambers.

Most politicians want to be in the public eye as much as possible; Briscoe’s extreme inaccessibility is one of the most striking facts about him. He has gone as long as eight weeks without a speech or formal public appearance of any sort. When he does appear in public it is usually a hermetic affair in which he is ushered to the head table, waits his turn to speak, and then either engages in a few moments of perfunctory handshakes or is whisked away before the program is finished. There is rarely any serious human contact.

The amount of time he spends in Austin, and what he does while he is there, are subjects he seems determined to shroud in obscurity. His aides have dismissed questions about his customary office hours as “insulting” and have declined to answer them. He himself has admitted he keeps no list of appointments, saying that he learns of his daily business agenda from “informal notes” passed to him by his secretary and “usually discarded at the end of the day.” If a corporation ran its headquarters with the same haphazard unaccountability, it would be out of business in six months.

Lee Jones, a Capitol correspondent for the Associated Press, recently tried to tally Briscoe’s absences from Austin by checking the flight logs of the airplane which the state makes available to its governors. The first obstacle was Briscoe himself, who tried to stymie Jones’ inquiry by contending that his logs of the state-owned aircraft were secret and confidential information the public had no right to see. An opinion by Attorney General John Hill, based on the state’s Open Records Law, made short shrift of that peculiar claim, leaving Capitol observers to wonder how anyone could have been so politically and legally naive as to suggest it in the first place.

The answer is that Briscoe may have been acting out of desperation: the logs were as damaging as everyone expected. They showed the governor had gone to Uvalde for at least a portion of the 135 days during the first ten months of 1975, including 64 non-holiday weekdays and at least one eight-day period during the last legislative session. That was a minimum: any additional trips he might have made in his own personal Lockheed could not be verified from the state plane logs.

In addition, when long-time Capitol newsman Stuart Long checked the state payroll records for “acting governors” who serve when a governor is out of the state, he found that Briscoe had been absent, not just from Austin but from Texas, on an average of one day every two weeks during fiscal 1975.

Despite the evidence, Briscoe’s executive assistant Ken Clapp continues to insist with a straight face that the governor usually leaves Austin “after work on Friday evenings” and returns “early on Monday mornings.” In truth, not only does Briscoe seldom keep such hours, for him to spend as many as five consecutive days in Austin is the exception, not the rule. Last December, for example, he spent a total of seven days in the Capital City.

Briscoe’s friends uniformly report that he seems happier, “more himself,” when he is away from Austin at the ranch. Lyndon Johnson did much of the work of his presidency at home in the Hill Country, so the real question is not whether Briscoe spends an inordinate amount of time in and around Uvalde, but whether he is attending to state business while he is there. The evidence is that he is not. Only three airplane logs showed members of the governor’s staff joining him for the flights, reinforcing speculation that his attention to official duties in Uvalde might be minimal. A caretaker at one of Briscoe’s Uvalde-area ranches told the Dallas Times Herald that the governor sometimes disconnects the telephones when he is there. The governor himself is evasive about his work habits away from Austin. When the Associated Press submitted a written question asking “what sort of communications and other facilities are available at Uvalde to enable [you] to keep in touch and do [your] job as governor,” Briscoe curtly returned their inquiry unanswered.

A public official should be judged in more important ways than the number or press conferences he holds. But Briscoe’s relations with the press have promoted his reputation as a phantom more by his own choice than by theirs. He has gone out of his way to promise regular news conferences and then has repeatedly broken his own pledge. On November 10, 1972, shortly after his election, Briscoe promised reporters he would meet with them regularly before the inauguration to discuss his legislative plans; he then virtually disappeared until January. At the beginning of the 1975 legislative session, he volunteered the promise to meet with reporters once a week; by April, he had gone five consecutive weeks without doing so. By May 1973, four months into his first term and deep in the midst of the legislative session, he had not called a single conference strictly devoted to answering newsmen’s questions. When he called in reporters to announce his opposition to the proposed constitution in October, 61 days had passed since his last “weekly” press conference. Challenged by reporters, the governor responded that, well, he might just have press conferences every 61 days instead.

Politicians commonly have friction with the press, but not in the way Briscoe does. The point is not so much that he tries so hard to avoid reporters, as that he makes gratuitous promises of cooperation, which he then does not keep.

Most of the encounters which the governor’s aides describe as “press conferences” are actually situations in which a few stray reporters have caught him in a hallway. As the governor wound up his speech to the Texas Research League last November, reporters for major Texas dailies whispered a request to this writer to join them at a door that seemed to be his most likely exit. “You don’t even need to have any questions,” one of them said. “We just need some more linebackers. If we can block the door, he’ll stop and talk to us for a minute, but if there are just a few of us, he slips right on by.”

Some of the governor’s absences have been downright baffling. In the weeks after his election, he remained in seclusion at Uvalde, not merely avoiding the press but also denying audiences to senators who tried to visit him. The first week of 1973 came; the Legislature came; but still, no Briscoe. He had scarcely begun to assemble a staff. House members joked openly about the “mystery man,” going so far as to ask whether the Speaker had formed a committee to “go find Briscoe and let him know we’re down here.” Two years later his behavior was even odder. A long-standing Capitol tradition calls for both houses of the Legislature to send a ceremonial delegation to the governor on the opening day of the session. The governor is expected to greet them politely, and they are expected to return and inform their colleagues that the governor has, indeed, greeted them politely. It is one of those ritual civilities of politics, symbolic of the separate but shared exercise of power: a gentlemen’s courtesy that politicians ordinarily enjoy. In 1975 Briscoe was inexplicably missing. Recalls a high-ranking Senate employee: “We sent five dignitaries, headed by [elderly East Texas senator A. M.] Aikin. A few minutes later Aikin came back, and the Senate asked for his report. He said, ‘We went to the governor’s office and it was locked. We found an aide who let us in the back door. He wasn’t there.’”

There are those who believe the governor is simply following in the footsteps of his distant relative Andrew Briscoe, who, having been elected to the 1836 Convention that produced the Texas Declaration of Independence, arrived nine days late for the signing. But for most people in the Capitol, the jokes have begun to wear thin. If the governor of Texas were nothing more than a figurehead, an American counterpart of the British monarch, Briscoe’s absenteeism could be dismissed as a harmless eccentricity. Instead he is an essential cog in the governmental machinery whether he wants to be or not. Regardless of whether a governor is liberal or conservative, public business cannot satisfactorily go on without him; the chief executive’s attitude affects state government in hundreds of ways, shaping decisions others must make even in areas over which he holds no direct administrative responsibility. His appointees to boards and commissions often want to know if he supports or opposes controversial policies before they make an irrevocable decision; legislators want to know if he plans to veto a bill before they expend their political capital trying to pass it. Because the governor does so much to set the tone of public affairs, even other statewide-elected officials need to know what he thinks.

Briscoe’s odd behavior has consequently impeded the conduct of state business in ways far more significant than his failure to greet A. M. Aikin’s entourage. One example is the experience of Forrest Smith, a tax attorney for Mobil Oil who served as Chairman of the Texas Youth Council (the state agency that oversees correctional facilities for delinquent children). He wrote the governor in January 1975 requesting an “urgent meeting” to discuss legislative matters affecting the council. Not only did he never get the meeting, his letter was never acknowledged. Three or four follow-up calls to Briscoe’s office were never returned. Smith—a Dallas conservative leader of some renown and a devoted Briscoe supporter who once personally introduced the governor as “a born-again Christian” at the First Baptist Church—is plainly puzzled by the experience. “I have no knowledge that he ever saw my letter or knew I’d called,” he says, “although I assume the messages did get through.” When Smith’s term expired in October 1975 the governor appointed someone else to fill the vacancy without any comment or explanation to him. Smith, who says he feels no rancor about the experience but seems to be a glutton for punishment, then wrote Briscoe a letter pledging support in the future. That was never acknowledged either.

Legislators have been particularly critical of Briscoe’s unwillingness to make his wishes known in time to affect the legislative process. In an example that could be multiplied many times over, one Houston representative wrote Briscoe a note two months before the 1975 session began, describing a pair of simple housekeeping bills and asking whether “you have objection to either bill, if they pass together.” He never heard another word. Under John Connally, Preston Smith, or any other Texas governor in memory, that sort of thing simply would not have happened.

An elected state official who was considering what he regarded as an “extremely significant” change in policy affecting the state’s revenues repeatedly sought Briscoe’s opinion on the controversial step. “For ninety days I left messages asking him to call me, but he never did,” the official says. “So finally I just went ahead on my own. If he were a governor he’d not only want to be consulted, he’d expect to be. I don’t think he even cared.” Legislative leaders including former Speaker of the House Price Daniel, Jr., and current Speaker Bill Clayton freely acknowledge that Briscoe has ignored important calls or letters; they are at a loss to explain why. One former state official, a friend of many governors, says, “I could pick up the phone and call Connally and get him—or he’d call me back. I could call Preston Smith and get him. But Briscoe? Impossible. It’s disturbing.”

Joe Allbritton of Houston, one of the nation’s most influential businessmen, was exasperated by his chronic difficulties in reaching the governor while serving as chairman of the Offshore Terminal Commission. General James Cross, who as the Commission’s Executive Director notified Briscoe’s office “numerous” times that Allbritton needed to see him or consult with him over the phone, says that during a period of two and a half years “I was unable ever to get in touch with the governor himself” on Allbritton’s behalf. While this was happening, the Commission was engaged in ticklish discussions about whether to recommend public or private ownership of the offshore superport.

Briscoe’s own department heads sometimes have difficulty seeing him. According to one, requests for interviews on “matters of paramount importance” ordinarily take five or six days to arrange (although there are rare instances when Briscoe has granted an interview almost immediately). Decisions on other matters requiring the governor’s answer or approval may take up to three months. He adds: “We [Briscoe’s department heads] have urged more ‘cabinet meetings’ because we need to know what direction he wants us to move in.”

Virtually every politician has an innermost group of trusted political advisers through whom outsiders develop a path of circuitous access. Roosevelt had his “kitchen cabinet,” Wilson had Colonel Edward House, LBJ had the informal “Texas Mafia.” By contrast Briscoe is a remarkable—one is even tempted to say unique—loner. Two months of interviews among politically attuned Texans, including statewide officholders, could not produce a single person who felt he could say with any assurance who Briscoe listens to. The politicians are as mystified as everyone else.

On frequent occasions in Austin, Washington, and elsewhere, Briscoe’s personal demeanor has conveyed the impression that he is curiously detached from his work. “He seemed unfamiliar with the issue” is a recurring phrase time after time in news reports of his press encounters. At one point last session, when he was asked about the school finance plan he had earlier labeled his “first priority,” it became painfully obvious that the governor was unaware a House committee had rejected most of his proposal two days before. A state legislator standing near Briscoe at a reception in May 1973 realized with mounting horror that the governor had failed even to recognize Education Commissioner J. W. Edgar. “How,” he shook his head sadly later, “can he solve school finance if he doesn’t even know the Commissioner of Education?” Another oversight had occurred earlier that year: several weeks into the 1973 session that saw a major fight over Briscoe’s marijuana and drug legislation, officials of the State Program on Drug Abuse, a division of the governor’s own office, were shocked to discover that he was ignorant of their existence.

While Briscoe stays deep in the background of his own administration, matters which need attention languish. By mid-January, the governor’s Energy Advisory Council (directed by law to formulate a state energy policy) had still not been called together for the regular meeting that was due in November 1975. Having pronounced himself an implacable foe of special sessions, Briscoe dithered for weeks in 1973 trying to avoid calling one that was plainly inevitable: the reduction of the speed limit to 55 mph in order for Texas to continue receiving federal highway funds. He finally called it for December 18, disrupting Christmas holiday plans for legislators and staff alike. He is notoriously slow in making appointments to state boards and commissions—one of the most significant powers a Texas governor has. A search of the Secretary of State’s register of appointments on December 1 showed dozens of vacancies, including some boards on which all the members’ terms had expired. One advisory council had 29 vacancies. Some divisions of the governor’s own office, like the Texas Film Commission, are under “acting” leadership more than twenty months after the previous director left.

Capitol observers are still incredulous about some of Briscoe’s protracted delays, like the nomination of Jim Wallace to a new district judgeship in Harris County. Wallace, a highly popular state senator who had sponsored Briscoe’s drug bill, had been checked out with everyone who mattered—including the local bar association, the Trial Lawyers Association, the defense attorneys, his Senate colleagues, and Briscoe’s own informal committee of Houston lawyers—and had received top marks from everyone. Even before the 1973 Legislature departed, it was widely understood around the Capitol that Wallace was in line for the job. “Well,” recalls a lobbyist from Houston, “Briscoe fiddled around with that appointment, and he fiddled around, and folks started going to see him. Finally Bill Hobby went to see him. He said, ‘Governor, you remember back when we were setting up this seat, everybody agreed that Jim Wallace ought to have it? Well, you know, Jim’s term is coming to an end, and I think you ought to go ahead and appoint him and get the uncertainty out of the way, because otherwise he’s going to have to run for the Legislature again.”

Months later, in 1975, Briscoe did appoint Wallace; but not until the uncertain senator had been forced to seek, and win, the Senate seat again. A special election costing $37,000 had to be called to replace him.

The situation prevailing on the State Banking Board is perhaps the most scandalous example of all. Charged with the responsibility of awarding new state bank charters—which are much-sought-after and potentially lucrative pieces of paper—the three-man board consists of two state officials and one layman who is appointed by the governor. Lay member James L. Lindsey’s term expired in January 1973, and Briscoe still has not named a successor. Under the law he continues to serve until the governor does so. Lindsey, who could win Senate confirmation without much trouble, says he “indicated to Briscoe soon after he took the governorship that I would like to be reappointed,” but he has heard nothing from the governor one way or another since that time. Because the other two members have a tendency to disagree about whether to grant new charters (Banking Commissioner Robert Stewart being more likely to frown on them than State Treasurer Jesse James), Lindsey has occupied the awkward position of a “holdover” swing vote for three years.

The failure of a banker-governor to act on such a crucial nomination to the Banking Board has caused extensive concern in financial circles. After Briscoe told newsmen at his last press conference in December that he had not given any consideration to the matter “lately,” Dallas Morning News reporter Sam Kinch, Jr., suggested that the prolonged delay might be “about to set a record for a holdover appointment.” Briscoe’s response, in its entirety, was: “What is the record?”

The results of Briscoe’s procrastination usually make no political sense. A case in point is the Joint Interim Surface Mining Operations Study Committee, created by the 1973 Legislature to investigate strip mining and present a report to the 1975 Legislature which would, thus informed, enact appropriate laws on the subject. The committee was to consist of three senators, three House members, and five “lay citizens” appointed by the governor. The legislators were ready to begin work when the session ended in mid-1973, and there was no real controversy about who the other members were supposed to be. Recalls a lawyer who followed the committee’s work: “It was one of those situations where the two protagonists—industry and the ecologists—agreed the study needed to be done, and had pretty much agreed beforehand on who ought to be appointed. Well, Briscoe just sat on his appointments—which were necessary before the committee could meet. Everybody was telling him about once a week, ‘Now goddamit, Dolph, we don’t really so much care who, just appoint somebody and let us get started.’” Why the delay? Senator Max Sherman of Amarillo, the committee’s chairman, says, “A lot of people tried to get him [Briscoe] to move, and he didn’t. That’s about all anybody knows.” Briscoe finally made his appointments on May 31, 1974, and by the time the legislators were finished with the Constitutional Convention in late July, only five months remained for them to complete the eighteen-month project.

With a sigh, the lawyer adds, “That’s what he does with everything. He sits on it forever, until you absolutely despair that anything is ever gonna happen, and then he finally does it.”

Visitors who manage to gain an audience with Briscoe often find the experience strangely unproductive. Several leading advocates of the proposed new constitution, who had been trying for weeks to win his support for the document, were finally allowed to meet with him on the day before he announced his opposition. Among those present were Attorney General Hill, Speaker Clayton, retired Supreme Court Chief Justice Robert Calvert, and state Representative Ronald Earle. “He greeted us all warmly,” one participant remembers. “He said, ‘I wanted you gentlemen to have the chance to discuss the constitution with me before I make my decision public,’ or words to that effect. We discussed one aspect that we thought he might disagree with, and then someone said, ‘Could you tell us any other concerns you might have?’ Well, he just smiled and said, ‘Oh, no. I couldn’t do that.’ So we had a little guessing game, talking about various articles. He just sat there, not saying anything, never asking any questions at all. The conversation kept lapsing. Finally we thanked him and left.”

Advisory groups that have worked on a nonpartisan basis with Texas governors for decades complain that he, unlike his predecessors, does not follow up on his agreements. “After we talked to Briscoe,” said an officer of one, “it was just like we’d never been there. It all disappeared.”

“Nothing happened”–that is the recurring complaint of those who deal with Briscoe personally. What frustrates them is not his reluctance to give commitments—that is a common ploy among politicians—but his lack of interest in discussing issues and his unreliability about following through on whatever commitments he does make. It is rare to find anyone who claims to have had a penetrating discussion with him about anything, including (especially) matters about which he has been outspoken, like school finance, and constitutional revision. What is he doing? His behavior is not devious, not the fancy skating of a skilled political operator. It is the indifferent behavior of someone who seems to care about next-to-nothing.

Among those whose work brings them into regular contact with the governor’s office, there is virtually unanimous agreement that many of Briscoe’s worst problems can be traced to his selection of staff.

From the beginning, Briscoe chose amateurs to run his administration. The Sharpstown Scandal did more than help elect him in 1972: it reinforced his own instinctive, homespun mistrust of political “types,” while at the same time making that mistrust seem entirely appropriate in the eyes of the public. Briscoe, who saw himself as a non-politician, came to power at precisely the time when non-politicians were becoming fashionable; and far from perceiving that there might be hidden risks in carrying that approach too far, he gloried in it. “Politics,” he told the bemused Legislature in his first address, “is not a game, and I will not play it.”

In the interval between his election and his inauguration he made only half-hearted efforts to persuade experienced Capitol hands like Jim Oliver to stay on; he shut himself off completely from old acquaintances like Walter Richter, a former state senator who headed the State Program on Drug Abuse, leaving them utterly uncertain whether they were supposed to remain or not. Eventually he surrounded himself with innocents: two lawyers with no substantial political experience, a school administrator, the pampered son of a small-town mayor. Only his press secretary, former LBJ man Bob Hardesty, knew any political ropes. The result was chaos: for while there may be something to be said for talented amateurs, there is nothing to be said for untalented ones.

“His organization,” says former Speaker Price Daniel, Jr., “is as poor as any I’ve ever seen. It borders on incompetence.” That is an attitude which, quite honestly, few knowledgeable people seem willing to dispute.

“Not only does he [Briscoe] not deal with people directly,” says a nonpartisan observer who has been in active contact with state government for years, “he doesn’t have a staff capable of dealing directly. Preston Smith picked good people and gave them some leeway. Briscoe’s staff doesn’t get anything done.” Says another: “The thing about Preston Smith was, at least he knew a lot about state government. Briscoe doesn’t. And Smith at least surrounded himself with some people who were pretty good; Briscoe has surrounded himself with idiots. They may be real bright in whatever it is they did before they came to the Capitol, but they don’t know a thing about state government. It’s frightening how stupid those people are.”

Both of these men had voted for Briscoe in 1972.

Shortly before Briscoe came out against the proposed new constitution last October, one of his top assistants called to discuss the document with a high-ranking aide to Lieutenant Governor Hobby. “We really like the Executive Article,” he confided, “and we’re gonna support that. But we just can’t go along with that Legislative Article at all.” Came the astonished reply: “But they’re the same thing! You know, ‘Proposition One: Executive and Legislative.’” “You’re kidding,” said the governor’s man.

Briscoe’s eventual opposition was based, he said, on a lengthy legal memorandum prepared by his aides. Over the course of two legislative sessions, Briscoe’s legal advisers have acquired a widespread reputation for strange, off-the-wall, alarmist interpretations of things that come their way—the mark, legislators believe, of the amateur who is unsure of himself. The reasons Briscoe eventually gave for his opposition to the constitution did nothing to dispel that view. One provision would have increased from one to 14 the number of courts available to hear appeals in criminal cases, and the number of criminal appellate judges from five to 42; Briscoe, amazingly, said he could not see how the criminal court reforms “could do anything but slow the process of justice.” He castigated another key provision allowing for annual legislative sessions, although the previous year he had endorsed a constitutional amendment which would have created them. He denounced as inadequate a provision enabling governors to have budget execution authority, although he himself had asked for precisely that power, in precisely those terms, the year before. (The popular liberal notion that the governor was acting as a cat’s paw for Houston industrialist George Brown and other conservative business critics of constitutional reform is emphatically disputed by the document’s leading supporters, who are convinced the decision was home-grown. “There is no evidence,” says Price Daniel, Jr., “that he was influenced by anyone outside his staff.”)

Acting on staff advice, Briscoe vetoed a rider to the 1975 appropriations bill which gave University of Texas regents the power to authorize construction projects without Coordinating Board approval. His action took a favorite toy (and a powerful political weapon) away from influential representatives of the political establishment among the UT regents and gave it to Briscoe’s friends on the Coordinating Board. “Those riders have been in the bills for sixteen years,” says former regent Frank Erwin. “He doesn’t have any power to ‘veto’ them; there’s a line of cases going back to 1911 that establishes that. Everybody knew it but his people. They don’t know the first thing about the legislative process.” In mid-December, the state Supreme Court unanimously found Briscoe’s attempted veto unconstitutional.

There is a distinct Keystone Kops ambience to the governor’s office. When Briscoe vetoed one House member’s bill, he gave reasons which applied to a different bill. Roy Coffee, Jr., Briscoe’s legislative liaison man in 1973, so infuriated legislators with his flagrant lobbying that he was ejected from the floors of both chambers, an unprecedented action in modern Texas politics. The legislative sponsor of a bill that Briscoe had expressly endorsed in his 1975 “State of the State” speech was thunderstruck to discover that members of the governor’s staff were going around bad-mouthing it to other legislators. On one memorable occasion, the governor called a press conference to sign a bill he did not have. Remembers a Senate employee mirthfully: “Everybody arrived in the governor’s office—reporters, cameras, dignitaries, the whole bit—and Briscoe said to an aide, ‘Where’s the bill’ ‘I dunno; I thought you had it.’ And so on, all the way around his staff.” A belated search uncovered the fact that it was still in the possession of legislative clerical personnel who were preparing it for signature. Such a staff goof would have been inconceivable with Briscoe’s predecessors.

The examples, large and small, can be multiplied. The small ones are the most inexplicable. When a group of schoolchildren raised the money to build a greenhouse stocked with state flowers, they wrote each state’s governor asking for seeds. A Briscoe aide wrote back, “Governor Briscoe regrets that we are not properly staffed to gather bluebonnet plants for distribution”—despite the fact that the Texas Highway Department has plenty of bluebonnet seeds, which it scatters along the medians.

Middle-level employees who brought some Capitol experience to the Briscoe administration have left, frustrated by the unprofessional atmosphere. Says one, a veteran of three decades of staff work for politicians ranging from conservative to semi-liberal: “All new governors have problems; that’s not unusual. But they [Briscoe’s people] didn’t seem to want to learn, or take advice. They seemed to be afraid and suspicious of the press and anyone who had been around the Capitol before. It’s not my job to set policy; I’m just a professional, and I want to do a good job carrying it out once somebody sets it. It wasn’t that I disagreed with the policy at all; it’s that there wasn’t any policy.”

Politicians deal with each other’s staffs all the time, and the experience does not ordinarily produce ill feelings; that is what makes Briscoe’s staff operation unusual. Politicians who want to work with the governor’s office go away shaking their heads. “Briscoe’s people are bothered by the vicissitudes of their responsibilities; it upsets them to have to do things. I nearly had fistfights with those sons-of-bitches when I went to talk to them,” grouses one state representative who doesn’t lose his temper easily.

The frustration is not confined to legislators. Heavyweight conservative lobbyists, including Searcy Bracewell of Houston, have had persistent difficulty with the governor’s organization. Says a fellow lawyer who has watched Bracewell’s efforts: “He can’t get Briscoe on the phone, he can’t get him to move, and so he does what everybody does—he calls Bob Hardesty or [Secretary of State] Mark White, the two people up there who know what they’re doing. It’s now gotten to the point, however, that you can’t get Hardesty or White. The line’s too long. Because nobody talks to The Man, and the guy has surrounded himself with clonkheads.”

Without exception, the most hair-curling criticisms are reserved for George Lowrance, a young San Antonio attorney who is in the key position of handling the governor’s appointments to state boards and commissions. Everything is fine as soon as we clear it with your senator, Lowrance tells prospective nominees, who know as well as he does that the custom of senatorial courtesy allows a senator to block confirmation of any objectionable gubernatorial appointee living in his district. Lowrance then calls the senator and says something on the order of: We’ve talked to Mr. So-and-so, and we’re ready to appoint him to such and such. Do you have any objection? If the nomination then falls through, the disappointed nominee knows good and well why, and the senator catches hell. This technique deprives the senator of any graceful way to forestall a nomination. It is another illustration of the way Briscoe’s operation flouts the usual civilities of politics. Says one veteran senator: “Preston [Smith] used to do this kind of thing every now and then; it was his way of punishing a senator for something. Briscoe’s people do it as a matter of course.”

The obvious question is, Why does Briscoe tolerate this kind of staff? The answer is, Because the only thing he really wants them to do, they do well. They protect his image.

Not only do they shield him from the politicians, the press, and an inquiring public, they also produce a blizzard of paper designed to give the appearance of activity where there is none. For all their lack of political skill, they know exactly how to flimflam the press. Announcements of Briscoe’s official nominations and other ceremonial doings are issued periodically, complete with quotes he never said; these find their way in due course to the state’s daily and weekly newspapers, where, presto! he appears as busy. The system has been perfected to the point where he could be dead, and no one might know for weeks.

One key image is always put forth in Briscoe’s speeches: that he is a decisive, firm, and forthright man. It is a rare address that does not contain at least one, “I firmly believe,” and the incidence of phrases like “I strongly believe” and “I feel very strongly” is usually high enough to take on the aura of cliche. His listeners are reminded of the “tasks” and “decisions that must be made,” requiring “all my energies” for such “pressing duties.” Like the Dr Pepper crate that John Tower’s aides conceal behind a podium so that he can stand on it and look taller, Briscoe’s speeches represent a well-devised effort to obscure the impolitic truth about him. Firmness: it says so right here. The average voter who knows almost nothing about state government except what he reads in the papers or sees in a ten-second TV clip can be satisfactorily hoodwinked by that kind of talk, in precisely the same way he fails to pick up the fact that John Tower is five feet six inches tall.

Briscoe’s staff members have successfully promoted this flattering image of their man, but otherwise the governor’s effort to turn his office over to political amateurs has been a failure of awesome proportions. What began back in 1972 as a vogueish attempt to portray himself as a leader who was independent of all those . . . well . . . nasty political forces that has disgraced Texas soon went awry; you cannot conduct an essentially political job by relying on people who are aggressively proud of their ignorance about things political. Beginning early in 1973, the accumulating avalanche of failures—staff failures—produced in the members of the Briscoe administration not a recognition that something might be wrong with them, but rather the firm belief that something was wrong with everybody else—all those tricky politicians out there who were laying traps, the political system itself. Says one state representative: “They react like you’re trying to put something over on them any time you want to discuss anything. You have to strain to convince them you’re being honest. They act like some country bumpkins who’ve come to town and think everybody they meet is trying to sell them the Congress Avenue Bridge; they’ve got that ‘ain’t no flies on me’ attitude.” Every failure reinforced the garrison syndrome that now dominates the Briscoe inner circle.

The conventional wisdom in state government today is to yearn for the return of “real politicians” to the governor’s office. Memories are short; the answer is not so simple. Is it easy, today, to forget the sinister mood that hung over the Capitol during the time when Briscoe’s most expertly “political” rival, Ben Barnes, was Lieutenant Governor: a mood (as those who knew it will remember) of deception and intrigue and spyings and knifings and things-are-not-what-they-seem which emanated not from Barnes personally but from the clique that surrounded him. When the Texas Observer headlined Barnes’ fall with DING-DONG THE WITCH IS DEAD, Capitol employees shared a sense of relief that was more than ideological. Briscoe’s staff is incompetent, but they do not deliberately generate an atmosphere of intimidation and fear. They are just part of the joke.

Briscoe’s foremost amateur—the person who, all things considered, is perhaps the ablest and certainly the most influential figure in his administration—is his wife, Janey. A bright woman who holds a masters’ degree in education, she enjoys being First Lady visibly more than her husband enjoys being governor. As a beauty queen at the University of Texas in the forties, the daughter of an Austin grocer, she found and married the soft-spoken rancher’s son from Uvalde. Her relationship to him soon transcended the usual devotions of a political spouse. When he became a state representative in the 1950s, she often sat beside him on the floor of the House. More recently, former members of the governor’s staff tell of seeing her sitting cross-legged on the floor of his office, opening his mail; it is widely believed that she answers much of it. She has her own department in the governor’s office called the First Lady’s Volunteer Program, complete with its own letterhead and five employees. The extent to which she hovers over him at public gatherings has become a familiar anecdote around the Capitol; “she protects him,” says an old-line lobbyist, “like she’s afraid he’s going to explode.” They are so inseparable that on one rare occasion when she was forced to leave his side for a few minutes—when he was ushered into the Oval Office to discuss energy policy with Richard Nixon while she waited outside—the Houson Chronicle considered the fact newsworthy enough to warrant a separate article headlined WHITE HOUSE SPLITS UP THE BRISCOES.

Her obvious devotion to her husband is never more evident than during his speeches. She will sit on the dais, turned at whatever angle is required to let her face him directly, and watch transfixed. Connoisseurs of this phenomenon say that on occasion as long as eleven minutes have gone by without her looking away. She nods gently when he is about to make a good point. Often she leads the applause; during his addresses to the Legislature, she has repeatedly interrupted him with clapping that gradually spread to the rest of the audience.

A Republican official who came down from Washington to attend Nelson Rockefeller’s White House Conference on Domestic Policy Issues in Austin last November found Janey’s performance during her husband’s address hard to take. “It was sort of creepy, really. It looked more like a mother watching her child get an award at a high school assembly than any sort of husband-wife relationship I’ve ever seen.” As a matter of fact, she has sometimes startled men in the macho world of Texas politics by referring to Dolph as “our boy.”

Her conduct has given rise to the pervasive rumor that Janey wears the pants around the governor’s office. That point of view got its quintessential nationwide airing in a 1975 Newsweek article captioned “Boss Lady”; it suggested that Janey “is really the governor of Texas—her husband, Dolph, just happens to have his name on the door.” It made Dolph furious. Bristling, but all the while keeping a fixed smile on his face, he told reporters that most Texans, including himself, don’t read Newsweek, “and those that do probably don’t pay any attention to it, like I don’t. I have no further comment.” Reporters have never seen him as upset about anything else.

The news media, in their fascination with the Janey phenomenon, have looked through the wrong end of the telescope. She is exactly what he has insisted she is: his “partner.” And the most significant thing about their partnership is not that Janey wields so much influence, but that Dolph wields so little. How can a man seek a position of power, achieve it, and then ignore it? Or if Dolph is not doing that, what is he doing? The question is far more intriguing than Janey’s role, which after all has been quite perceptively explored by Shakespeare in Macbeth.

If the strange crew that occupy Briscoe’s office were in fact carrying out some sort of conscious program, no matter how ill-conducted, one could at least feel there was some useful purpose to what is going on. But they aren’t; and there isn’t.

The Briscoe administration’s program—or what would be the administration’s program if it had one—can best be viewed as a pyramid. At the broad base are his ghostwritten speeches, which recite problems, priorities, and things that need to be done, all carefully spelled out to buttress the necessary appearance of activity. The best of them are excellent. His two “State of the State” addresses in 1973 and 1975 were cogent, occasionally eloquent, explorations of Texas’ condition. During the ensuing legislative sessions, however, his administration ignored or mishandled most of what he had said and backtracked on much of the rest. That, then, is the middle of the pyramid: what his staff actually does.

After Briscoe called for action to import water to the High Plains, including passage of water development bonds, his staff was so unconcerned about the necessary legislation that they dumped the entire matter, including the selection of a sponsor, into the lap of Lieutenant Governor Hobby. A legislator carrying a bill to permit the admission of oral confessions into evidence (one of the key planks in the governor’s anti-crime package) asked Briscoe aides for help in passing it but could recall nothing to indicate they had actually done so. With great fanfare in his 1975 address, the governor announced the creation of a special toll-free long distance telephone assistance service called TEX-HELP, the aim of which was “to make government more available and more open” to anyone “who needs assistance or information involving state government.” The toll-free number is 800-292-9600 but unless you live in Austin you won’t find it in your local telephone book.

Quite apart from the question of whether Briscoe’s administration has selected the right goals is the question of whether they have pursued them in a way calculated to achieve results. Consider the 1975 session’s dominant issue: school finance. At the end of the previous session, Briscoe hired respected educational consultant Richard Hooker, who worked for eighteen months and produced a school finance plan that was theoretically admirable but politically unrealistic. As submitted to the legislators, it entailed substantial tax increases at the local level and it was geared, in the words of one top education expert, “to walk all over the TSTA” [the Texas State Teachers Association, whose political muscle is legendary]. Having thus misread the politics of the 1975 Legislature, the governor’s people then proceeded to refuse any compromises—“which would have helped a lot at several points,” says the expert. “It was obvious very early that the bill was going nowhere in the House, yet no effort was made to modify it to meet the objections and try to salvage something.” The governor himself, who had been extremely supportive of school finance reform in his pre-session speeches, failed to assemble the legislative leadership for a personal selling-job that might have rescued his otherwise doomed bill. The version that finally passed was hastily put together in the Senate during the last two weeks of the session, and though the governor was by then willing to compromise, very little of his original proposal was left.

The real question is what Briscoe himself has wanted done. That, then, is the pyramid’s tiny tip: the issues in which he as an individual, not as an “administration,” has taken a direct, discernible personal interest. What does he himself really want to do?

The answer given by many who have observed and worked with him most closely is, virtually nothing. “I really don’t know of a single piece of legislation he’s taken a personal interest in,” said former Speaker Daniel. “No new taxes,” said current Speaker Clayton, “but that’s all I can think of.” Although Briscoe is popularly regarded as a conservative, his personal political “program” is not so much conservative as it is reactive.

What does he react to? Politicians who have dealt with him agree on two things:

• He resists anything that he interprets as diminishing the power of the governor’s office, regardless of how trivial it may be; and

• If he is ever directly confronted over something, even by accident, he fights hard to avoid losing.

The result has been that a high proportion of the issues in which he has involved himself personally have not been ones that he chose, but rather ones that were thrust upon him by others. Trying to discern a program in all this is impossible; there is none.

The three major displays of gubernatorial arm-twisting in the last session came on the Coordinating Board bill and the confirmation of his appointees Walter Sterling and Hilmar Moore. In the confirmation cases, two of his long-time personal friends were opposed by Senate liberals; he generated a ferocious counterattack to put the liberals down. In the other case, he expanded the power of the Coordinating Board (dominated by his own appointees and chaired by his close friend Harry Provence) against the indignant opposition of the University of Texas regents.

Anything that erodes executive power is likely to meet his personal opposition; he is more interested in keeping power than in using it. A provision in the new constitution that would have made gubernatorial appointments expire after February 1 of odd-numbered years, thereby eliminating “midnight” appointments by an outgoing governor, was regarded as a plot hatched in Bill Hobby’s office to snatch away Dolph’s rightful future powers. An uncontroversial bill revising the rules governing emergency medical leaves for penitentiary inmates—which had the support of prison officials and the Board of Pardons and Paroles—was vetoed; it had taken away the governor’s existing (but practically never used) authority to countermand those leaves.

If there is anything that characterizes Briscoe’s relations with the rest of state government, it is this petty insistence on preserving abstract power. At times it seems that not only does he not want to do anything himself, he does not want anyone else to do anything. There are those who see the hand of Janey in all this, protecting her husband from imagined threats to his authority; others see the hand of his staff, unable to distinguish between power that matters and power that doesn’t. But the truth may be that Dolph himself, the soft-spoken son of that two-fisted rancher, is behind it: proving to any doubters that he is not some weak-kneed Milquetoast who lets others get the best of him. Remember those speeches: he is a man of firmness.

Insofar as Briscoe has a personal program, this idea of forbidding things is its dominant motif. Forbidding people to take away his power, forbidding them to get the best of him; and above all . . . forbidding any new taxes. That is the one continuing policy year-in-year-out which elicits his whole-hearted enthusiasm. It is the sole irrefutable accomplishment of his three years in office. One illustration will suffice to show the depth of Briscoe’s attachment to this, his single monument:

Texas has never imposed a tax on refineries; legal authorities agree this could be done, and one state (New Hampshire) has already done so. The tax would get passed along to the customers who buy the refineries’ products, of course, but because so much of the nation’s petroleum is refined in Texas, a majority of those customers are out-of-state; thus, whatever share of the tax they pay, Texas gets to keep, free and clear. It is, all things considered, a nifty way to skim off for the benefit of home folks some revenue from the petroleum that passes through or from our state. A refinery tax is potentially a huge moneymaker: the Legislative Budget Board has estimated that a rate of a penny a gallon would yield a billion dollars per biennium—about the same as a state income tax. During the 1975 session, Speaker Clayton, Lieutenant Governor Hobby, and House Ways & Means Chairman Joe Wyatt brought up the idea of a refinery tax with Briscoe. Clayton inquired whether the governor would consider signing one if another existing source of revenue, like the sales tax, were reduced by an equivalent sum—an exchange that would actually lighten the tax burden Texans must carry. Briscoe said no because it would be—that’s right—a “new” tax.

The shibboleth, No New Taxes, and its corollary, Cut Back Government, call to mind California Governor Jerry Brown. The controversy between traditional liberals and traditional conservatives today has essentially degenerated into little more than a dispute over who should get the government’s money. Though Briscoe’s more sophisticated Austin critics may not want to believe it, both he and Brown are in touch with a genuine, and rising, public desire to restrain government’s apparently limitless growth, a desire that may be the coming thing in contemporary politics. The difference is that Briscoe’s understanding stops with the crabbed assumption that the best government governs least, while Brown perceives that even the best government has limits to what it can accomplish. Briscoe concludes “it is not the duty or function of government to solve all the problems that exist in today’s society”; Brown concludes “there are problems that cannot be solved. . . . There may be no solution other than acceptance.” One philosophy reflects unconsidered dogma; the other, the experience of the past 40 years of American life. Briscoe is satisfied to cut back the number of problems that government should feel a responsibility to help solve; Brown is sobered by the realization that when government tries to solve problems it may be powerless to succeed. Given the complexity of the times, Brown’s view has the ring of truth and Briscoe’s, though superficially similar, is merely an archaism.

Another difference, of course, is that Brown is trying to act on his discovery, while Briscoe is largely just talking about it. Neither on taxes nor on controlling governmental growth has Briscoe faced the issues directly. He has not been tested on his tax pledge because the state’s anticipated deficits in 1973 and 1975 were unexpectedly cancelled by a windfall of extra oil and gas tax dollars produced by the higher petroleum prices, by federal revenue sharing and social services reimbursement, and by inflationary increases in sales tax revenue: none of which he had anything to do with. His idea of forestalling a future tax increase by squirreling away part of the plump 1975 surplus into a working capital reserve account came to naught because legislators instinctively hate to leave money lying around on the table unless they are absolutely forced to, and Briscoe, true to form, failed to roll up his sleeves and play the tough politics required to force them. As a result, state fiscal experts anticipate “a tax bill of unprecedented size”—that means, around a billion dollars—in 1977.

Briscoe’s attempts to control governmental growth have largely consisted of cutting back the number of employees in the various branches of the governor’s office from 510 to 336, a plan that sounds like a good start until one notices that many of them have simply been shifted to other slots in state government. The Comprehensive Health Planning Unit, for example, was moved from the governor’s office to the Department of Health last year. Many former employees of the governor’s defunct Office of Information Services, a computer-coordinating bureau, now work for Comptroller Bob Bullock, who estimates that 95 per cent of the original group are still on the state payroll somewhere. Bullock says he has even received letters from the governor’s top aides asking him to hire people they are trying to unload.

Briscoe’s hiring freeze has produced some queer results. For example, it has prevented the replacement of many departing employees whose salaries are paid by federal grants instead of state taxes (some sections of the governor’s office are more than 90 per cent supported by federal money). While this technique is at least saving some tax money, even if it isn’t state tax money, its usefulness as a means of reducing the federal budget is akin to Lyndon Johnson’s thrifty penchant for turning off the White House lights. And because federally salaried positions carry a 15 to 20 per cent bonus payment directly to the state for overhead expenses, each new vacancy takes more money away from the people who remain to carry on the operation. The reductio ad absurdum of all this was reached when the growing shortage of full-time secretarial and clerical personnel forced some departments to hire part-time “Kelly-Girl”-type assistants, who hour-for-hour are more expensive than the employees they have been brought in to replace. The upshot, admits Briscoe’s budget director Dicky Travis, is that the actual cost of running the governor’s office has gone up, not down.

No wonder, then, that morale among the surviving employees has been plummeting for months. By January, surreptitious job-hunting was widespread.

Briscoe’s meat-cleaver attack on governmental growth shows how simplistic his understanding of the state’s entrenched bureaucracy really is. Whatever governor eventually does prune down its size will succeed only by first using his personal leadership to win broad public support for the inevitably bitter and protracted fight. Though the Texas electorate may soon be skeptical enough of big government to grant that support, Briscoe has shown no inclination to invoke the governor’s personal leadership for that battle or for anything else.

It should go without saying that Briscoe should be judged on the (basically conservative) things he wants to do, rather than on the (basically liberal) things his most vocal critics would prefer him to do. But you do not secure a niche in the pantheon of conservatism by botching conservative goals.

To stand back and contemplate the ongoing fiasco that is the Briscoe administration is to find oneself asking how such a remarkable political phenomenon could occur. 1972 is easy to explain: Sharpstown: a broke, liberal woman for a runoff opponent: a fluke. But what about 1974? Not why did Briscoe defeat Farenthold; that is easy. But why did he have no other opponent? Not Hobby, not Hill, not Armstrong, no one. If Briscoe and his people were so hopelessly overwhelmed by their job that the office was in a permanent condition of collapse, why did the conservative business interests—whose political clout is great and who after all can no longer enjoy the luxury of a government that does nothing—not find someone to take Briscoe’s place?

The answer is that although the discontent with Briscoe runs wide among conservatives, it does not run deep: he was safe on taxes, and he was safely in office keeping out some liberal who, in the business community’s eyes, would have been worse. Since a second term has traditionally been automatic for Texas governors, the effort to unseat him would have been prodigious, and it might have failed. Why bother? They could live with him; and at least he was, in his idiosyncratic way, predictable. “Predictability is very important for business,” says one lobbyist. “Briscoe is a no-motion guy, which is an identifiable result, and you can predict and go forward based on that result. That far outweighs the down side of no access when you need him.”

So they kept him; they kept the man who wasn’t theirs, who was a front man for nobody; the man who drove them up the wall, predictably. He was a fluke, but he was a useful fluke. And when he gave his fund-raising dinners they turned out by the hundreds, more than had ever turned out for anyone in Texas before; and they told him Dolph, you’re great.

But as soon as he was gone they laughed at him; laughed at their accidental good luck to have someone like that around: not just what we’d have wanted, you know; pretty weird in fact; but safe, that’s the main thing, safe. Tell him he’s great; he’ll never catch on.

Whatever Dolph Briscoe’s muse may be, the cumulative effect of his behavior has been to deny him, as governor, the unequivocal respect that had come his way spontaneously in private life. Can he not know that? A poignant reminder of the change was the celebrated “Orville Drall” caper last legislative session, in which a simulated press release from a fictitious state representative of that name announced the introduction of a resolution declaring Dolph Briscoe legally dead. Yes indeed: everyone got a good laugh over that one, including (they say) the governor himself; but when he was alone with his thoughts that night, what then? Did his memory roam back to Uvalde; and those first parades; and what it had all meant then, so long ago?

II

Why does Dolph Briscoe want to be governor? Years ago, he himself gave this answer: “You just go through life one time. I think you should try to do everything you can, serve wherever you can.” A man does not, however, pursue something as hard-to-get as the governorship merely to fulfill Duty’s abstract call; he seeks it for some reason. And the unavoidable fact about Briscoe is that none of the traditional reasons men go into politics seem to apply to him.

Executive command? He does not relish it in the manner of a Roosevelt, a Kennedy, a Johnson; his lackadaisical attitude toward his own appointments suggests he does not relish it at all.

A program? He has none, save for a small handful of taboos, of don’ts, of forbidden things like No New Taxes; after three years he has yet to develop and work for a coherent set of legislative enactments.

The pomp and ceremony of the office? He seems indifferent to it. He is feted at his speeches, to be sure, but he often drives away in a red Ford, not the official Lincoln Continental limousine. He seldom socializes at the mansion, rarely has parties at which he, the governor, could bask in adulation. When critics call him another Preston Smith, they could not be further from the truth. The two men are profoundly unalike: Preston loved the usufructs and fanfare of the governorship, reveled in them as much as Dolph ignores them. Briscoe is, in the currently fashionable language of the political science fraternity, a classic “passive-negative” executive. Not only does he not do anything, he seems to have no fun not doing it.

Money? Not a chance. A $65,000 salary is not exactly opulence for a multimillionaire, and if there is anything the Briscoes didn’t need, it was another house. Besides, as their old friend Zeke Zbranek opined, “Ol’ Dolph had a pretty good car when he came.” And the idea of pilfering from the public purse is abhorrent to what everyone agrees is Briscoe’s scrupulous personal honesty. Whatever else Dolph Briscoe may be, he is not a crook.

Political kingfishery? He has shown no interest in securing a place as a party boss, as, say, Shivers did; the State Democratic Executive Committee, which he controls, is down to one secretary and is deep in debt.

Cronyism? Analysts of the Texas governorship have remarked that the most noticeable characteristic of the state’s chief executives since Reconstruction is that they have been front men for other interests. (As someone once remarked of Ben Barnes, the young state representative from De Leon whom the Connally-Johnson Democratic establishment groomed to preserve their control of the Capitol until Sharpstown and Briscoe upset their plans: “They interviewed a lot of people for the job, and Ben Barnes got it.”) Briscoe, by contrast, is not just another front man for corporate business interests; they are frustrated by him personally, even though they are not especially unhappy at what he does. He is a fascinating anomaly in modern Texas politics.

It is not hard to discern definite personal reasons, however, that induced him to put a gubernatorial construction on Duty’s call. His father’s deathbed wish was for young Dolph to become governor. Friends remember the older man as a “backwoods Joe Kennedy” who bred his son from childhood for that office, and the father’s influence is so strong today, 22 years after his death, that Dolph still puts Jr. after his own name. Beyond that, of course, there was the prestige of the office itself. The Texas governorship has been the terminal political achievement of those who hold it, a kind of pinnacle in itself; to Price Daniel in 1958, it was worth leaving the U.S. Senate for. In Texas the governorship is something.

It has prestige, and Briscoe has always gone after the prestige spot—an objective that has less to do with any specific set of goals than with the luster of the position attained, rather like being the titular chairman of a charity fund drive. Precisely: First of the Bankers, First of the Ranchers, and finally First of All the Texans. The crown of a career.

Then too, there is Janey. Not only does she have an abiding interest in things political, she also has plainly drawn vicarious pleasure from her husband’s lifelong ascent in status and esteem—which (alas) was taking place in the relative obscurity of a small South Texas town. For Janey, who grew up in a salt-of-the-earth social-climbing family surrounded by, but not part of, Austin’s tantalizing political and social whirl, marrying Dolph was marrying up. And getting Dolph elected governor was the great escape: a ticket out of Uvalde and back to her hometown in triumph—not merely a ticket of admission to that world she had seen as a child, but admission to the very top of it, able to ordain what that world would be.

All of these things doubtless motivated Dolph to run for governor; but are they enough? Does a shy, aloof rancher really leave the wild solitude of the place he loves and endure two state-wide political campaigns and the vexations of Austin in order to please his wife, add another feather to his cap, and lay to rest the ghost of his father? There must be more. What is it? “The reason,” said a former state official as he turned in his swivel chair and gazed for a long time at the stark winter scene outside his window, “is that he enjoys the power.”

The power?

The power. “He enjoys the power that sets him apart. The lofty pedestal. Being above the crowd, able to deal with people as you please with no accountability. That kind of power. Not the other kind.”

He saw my puzzlement. “Let me tell you a story,” he said. “Dolph and I were friends back in the fifties. I admired him, and when he retired from the Legislature because his father had died, I wrote him a letter regretting it, telling him how sorry I was to see him leaving public life and how I hoped he’d be able to come back some day. We kept up a good personal relationship for years after that; I used to go down to Catarina [Briscoe’s ranch headquarters] and fish with him. Naturally, when he became governor we didn’t see as much of each other. But one day I was cleaning out some papers in my office and I ran across a copy of that old letter. I decided to send it to him, along with a little note about the old days and how he had come back after all—not just come back, but come back as governor. Dolph never acknowledged it at all.”

He was not angry. He was hurt; you could tell the difference easily in his eyes. You understood he knew the note was unimportant by itself; you understood without his saying so that it had been meant to say, Dolph, we were together long enough ago for these pages to turn yellow, and I am still your friend. There are tokens that pass between men as affirmations of friendship. This was one.

There is nothing unique about this type of story. Kind personal notes from men as prominent as two former governors have gone unanswered. The more one looks, the more one finds that the distinguishing mark of his relations with the political and social world of Texas has been to emphasize that he is set apart—to do things that remind others he is dealing with them as he pleases. Many of his most inscrutable actions can be explained, at least in part, as a way of saying two things to other people: “I Don’t Need You,” and “Whether You Like It or Not, You Have to Wait on Me Now.” That represents the exercise of power in a very special sense.

It helps explain his failure to greet the legislative delegations on the first day of each session; politics, for all its infighting, is soothed by a network of ritual courtesies among politicians, which are precisely the things Briscoe spurns. It helps explain the unanswered inquiries from legislators asking if he has any objection to their bills. It helps explain the appointments that go unfilled while impatient committees and agencies cool their heels. It helps explain his chilliness toward people who offer him advice, especially old friends; and the phenomenon, often noted, that he subsequently goes out of his way to show he is ignoring it. It helps explain his indifference to almost everything the Legislature does except those that challenge his supremacy or dilute the power of his office.

It helps explain, too, why he would assemble the Capitol press corps for an announcement of his intention to have weekly press conferences and then let 61 days elapse without one. He knows they will arrive incensed, knows someone will stand up and asking, fuming, “Governor, since you said you’d see us every week, why . . .”—but you can finish the question yourself, as he could. Ah, the press; they are all so predictable; they perform on cue, his cue, turn on the lights and watch them go nuts. It’s been eight weeks or so, shall we invite them back for another show? Let’s do. Meanwhile they never catch on; they just chase him around to Rocksprings and line up their friends to block the doors, where he can smile politely as though nothing is wrong and give a few nonresponsive answers. There’s nothing they can do about it, and it’s fun to watch.

The contrast between Briscoe’s unvarying politeness in person and his passive rudeness when he is safely cloistered away from human contact has left many of those who deal with him confused. They begin by telling you what a “nice man” the governor is, but if you visit long enough they finally confide some chilling personal story which contradicts that—some strange sad puzzling recollection over which their memory eventually trips, which they offer to you uncomfortably, tentatively, apologetically, in the form of a confession. “Although he didn’t acknowledge my letter pledging my future cooperation,” said a bewildered Forrest Smith months after Briscoe had deposed him from the Texas Youth Council, “I assume he did get it and appreciates it.” “I don’t know what the situation is,” said a former governor who had written two personal notes. “I never heard anything again, but everything is friendly whenever I see him.” Did you ask him about the letters in person? “Yes. . . . He was friendly but unresponsive.”

Unanswered letters from ordinary citizens could be passed off as bad staff work; letters from prominent people, old friends, former governors, no. Forrest Smith’s story of letters ignored and phone calls unanswered was in the newspapers; a staff that could shield the governor from knowledge of that would have to be dealing with a man who could not read. No, he knew; and he made his choices.

He enjoys the power. Yes: the power to make people worry about him, to need to know what he thinks, to beseech him a bit; the power to ignore those who think they know the answers; the power to ignore his friends. For all these reasons, his behavior on the proposed new constitution was utterly predictable. Not merely that he opposed it, but that he waited so long to say so. In the same way that he had dozed through the Constitutional Convention of 1974—resisting every invitation to participate until, on third reading of the Legislative Article he abruptly produced a list of surprise objections that forced everyone to stop and change things according to his demands—Briscoe concealed his opposition to the constitution until the last possible moment. He had a right to take whatever position he chose, and there were adequate reasons for him to oppose it; but no one can read his statement without realizing that he did not give those good reasons, nor even particularly care what they were. He was against it regardless of the reasons—partly, at least, because Hobby, Hill, Armstrong, Daniel, Calvert, Hutchison, and all the rest had banded together for it. He set them up for the fall; for two years he said things that sounded like endorsement for constitutional revision, set up applause lines for it in his speeches, sounded like he was for it but never quite said so. He let them all climb out on a limb, from which precarious perch they regularly reminded him that new state constitutions do not pass these days, anywhere, unless the governor puts his full weight behind them. They climbed without him, and three weeks before election day he sawed the limb off. Immediately, just like those press conferences, the howl went up. One legislator fired off a three-page letter, dismantling the governor’s arguments as though he were picking wings off flies, and drawing himself up to full height to huff: “Your statement is . . . a personal affront to the Legislature and every member elected to serve in the House and Senate.”

Exactly so, just what it was intended to be. The constitution failed, you see; without his support, it failed. They thought they knew so much: but in the end, they needed him.

Briscoe’s behavior ultimately reveals why he wanted to be governor. It is the behavior of a man who had everything which should have conferred the undisputed highest status—vast wealth, award after award, more land than perhaps any other Texan—but who still was not quite part of the inner circle of the Texas political and social establishment. He was everything in Uvalde, but in a sense that just made things worse: knowing that your position has begun to lose its luster when you get past San Antonio, and that by the time you get to Houston and Dallas, where the movers and shakers are, you are just a very rich, very nice South Texas rancher. The contrast was inescapable. Status, after all, is not a matter of hobnobbing with the rich and powerful, which Briscoe could do any time he chose, but rather of the subtle way the rich and powerful hobnob with you: whether they regard you as one of them. As much as Briscoe was admired by those people, it never quite occurred to them that he was one of them. And he knew it.

Worse still, he knew he was real landed gentry, someone who came by his land rightly, who had it before he entered politics: not like the Connallys and the Johnsons and the rest who got theirs afterwards. As landholders they were the imitators; he was authentic. They were parvenus, but they captured the status that eluded him.

For him, the governorship was a way to clinch that last full measure of respect. It is the one position that is by definition, unambiguously, the First Citizen of Texas; and whoever occupies it has pre-eminence. Briscoe’s lingering hope that establishment circles would somehow recognize his achievements and anoint him voluntarily had begun to fade in 1962, when Connally received the nod, and was dashed for good in 1968, when he felt his turn had come and they followed Locke and Carr and Hill and Smith instead. That was the moment of truth, the end of his most fundamental illusion, and it came as a terrible shock. From then on he knew he could count on no one but himself, that he would have to get the governorship and that last full measure of respect entirely on his own. He is a different man now than he was in 1968; more than any other reason, that is why. “They may not think I belong at the top,” his attitude became, “but if I ever get there they are going to have to come to me.” People who think like that usually do not get to be governor; but 1972, as luck would have it, was an unusual year.

Briscoe ascended to the governorship with certain profoundly anti-establishment feelings: anti the politicians, anti the conservative business establishment’s leaders (but not its goals), anti the people for whom the social whirl was everything. What part Janey may have had in shaping these feelings—who can say? The administration in which she plays such a leading role, however, manifests them pervasively, starting with the staff of amateurs that surround the governor. The choice of a complete unknown like Calvin Guest as chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee has emphatically reminded the political establishment that they no longer control the game. Searcy Bracewell’s calls go unreturned; political appointments go to Uvaldeans who pose no latent threat of put-down. If there is any social power in Austin greater than the power to decide who is invited to the governor’s mansion, it is the power to decide who is not invited there. Under the Briscoes not only are the parties few and far between, but also old personal friends in Austin—friends close enough to have made regular annual visits to Catarina for years before Dolph and Janey moved to town—remain coldly and inexplicably uninvited inside the mansion’s door. To invite the social establishment would be to risk the chance their acceptance might still be withheld, somehow, in spite of everything; to invite plain old friends would be an admission that you were still, somehow, no better than their equals. It is lonely at the top.