His name was Ezequiel Amaya Escobar, although no one knew who he was when his body was discovered one morning last August under a mesquite tree. He was lying five and a half miles from the nearest paved road, in a stretch of South Texas scrubland that Spanish explorers once called El Desierto de los Muertos, or the Desert of the Dead. The austere landscape, which extends from Kingsville to Raymondville, is a patchwork of ranches that includes two of the largest in the country: the King Ranch, to the north, and the Kenedy Ranch, to the south. A Border Patrol checkpoint stands roughly in the middle, on U.S. 77, and Ezequiel had died trying to walk around it. When he was found, his head was resting on his backpack, as if he had stopped in the wilderness to take a nap. He almost looked alive; he had thick black hair that fell just below his ears, and his face was soft and round. But his lips were cracked, his eyes wide open. He was thirteen years old.

What little is known about Ezequiel sits in a white banker’s box in a storage room of the Kenedy County courthouse, in Sarita, wedged between the more than one hundred case files of other undocumented immigrants who have died near the checkpoint trying to make their way north. His death never made the newspaper. According to a typewritten report from the sheriff’s department, he had been classified, at first, as a “John Doe” until he was identified by his mother, whose phone number he had written, in indelible ink, on the label inside his T-shirt. He had come all the way from Honduras. His friend, fifteen-year-old Jesús Edgardo Marcia Abrego, had told investigators that Ezequiel had lagged behind the group they were traveling with as they trekked through the brush. After more than a day on foot, he started to show signs of heat exhaustion. He began to vomit as he struggled to keep up, and as the hours wore on, he had convulsions. That evening, he dropped to the ground and stopped breathing. “Jesús said he gave him mouth-to-mouth, but he did not respond,” the report states. “He wasn’t able to feel a pulse and saw that his eyes had rolled up into his head and he knew that [Ezequiel] was dead.”

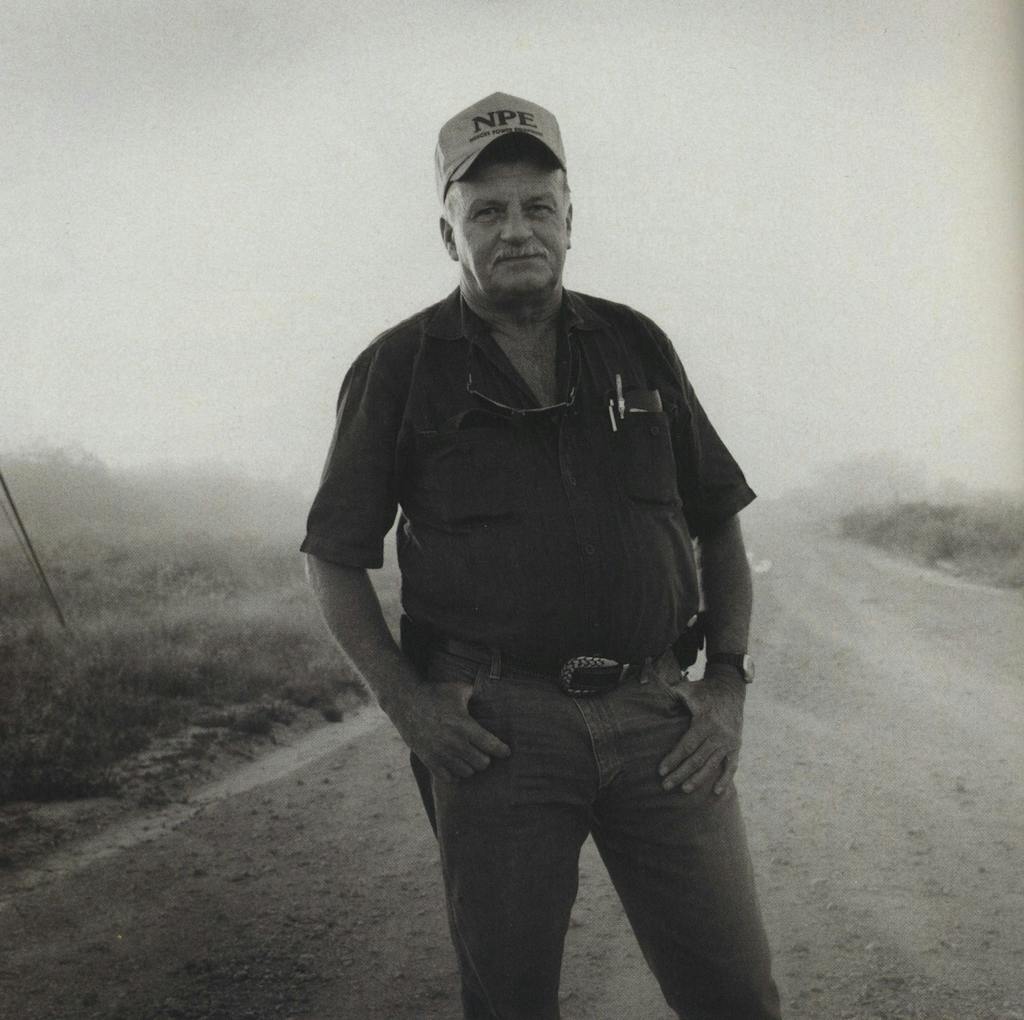

Donald Strubhart was the man who had found him. In late June I went to see Strubhart at the ranch he manages, Cielo de Cazadores de Codorniz. The property, which shares a fence line with the King Ranch, sprawls across 125 square miles of sand dunes and catclaw and scrub brush. Strubhart, who is 58, gave me a warm handshake and suggested that we talk while he made his rounds. The air was hot and dry and still that morning, and as Strubhart eased his pickup out of the driveway and began to head south, we passed some Longhorns napping in the shade. His quick blue eyes were shaded from the glare by a ball cap from a local farm-equipment company, and his salt-and-pepper hair poked out from under it. As he drove, he began to talk about the staggering number of people who had passed through the property in the spring. “From Easter until the beginning of June, it seemed like there was an exodus out of Mexico,” he said. “There were days in May when all I did was call Immigration. We spent most of our time repairing fences that had been tore up, and then more people would come through. Seemed like it would never end.”

A doe froze in her tracks, startled by the rumbling of his diesel engine. Strubhart continued on, and after a while, he rounded a bend and pulled the truck over to the side of the caliche road. He walked a few paces and then stopped at a mesquite tree. “This is where I found him,” he said, and fell silent. He used the edge of his boot to nudge an empty, rusted can of Sterno that lay on the ground. Sunlight filtered through the branches above him. “I’ve worked on this ranch for ten years, and in that time, I’ve found five people dead,” he said. “This one hit me harder than all the others. I spent a little over a year in Vietnam, and this boy carried me back. American boys died over there for no reason, and it made me sick. And that’s what I feel about this boy—he died for no reason. Eventually I’ll get over what I saw in Vietnam, but I don’t know if I can get over this kind of thing.”

He looked out over the ranch, which a lack of rain had turned dry and brown. “A child died out here, under this tree,” Strubhart said. “I don’t have the answer to what we should do about people coming over the border. All I know is no one should have to die this way.”

NINETY MILES NORTH OF THE RIO GRANDE, the Sarita checkpoint is the last threshold that undocumented immigrants must cross after leaving Brownsville behind. Some manage to slip through, hidden in the traffic headed north—squeezed inside unventilated tractor trailers, crates of watermelons, piñatas, suitcases, car trunks. But most pay a coyote, a smuggler, to guide them around the checkpoint, walking for as many as four or five days through the desert. They bypass the town of Sarita, a small, dusty, unincorporated community on the Missouri Pacific railroad line where a solitary yellow traffic light blinks over the highway. Just 417 people live in Kenedy County, and it is possible to drive through Sarita, its only town, without seeing a soul. There are no cafes, no gas stations, no convenience stores. Judging from my first pass through town, Sarita seemed to be inhabited by two little boys on bicycles, who circled the courthouse, and a stray dog.

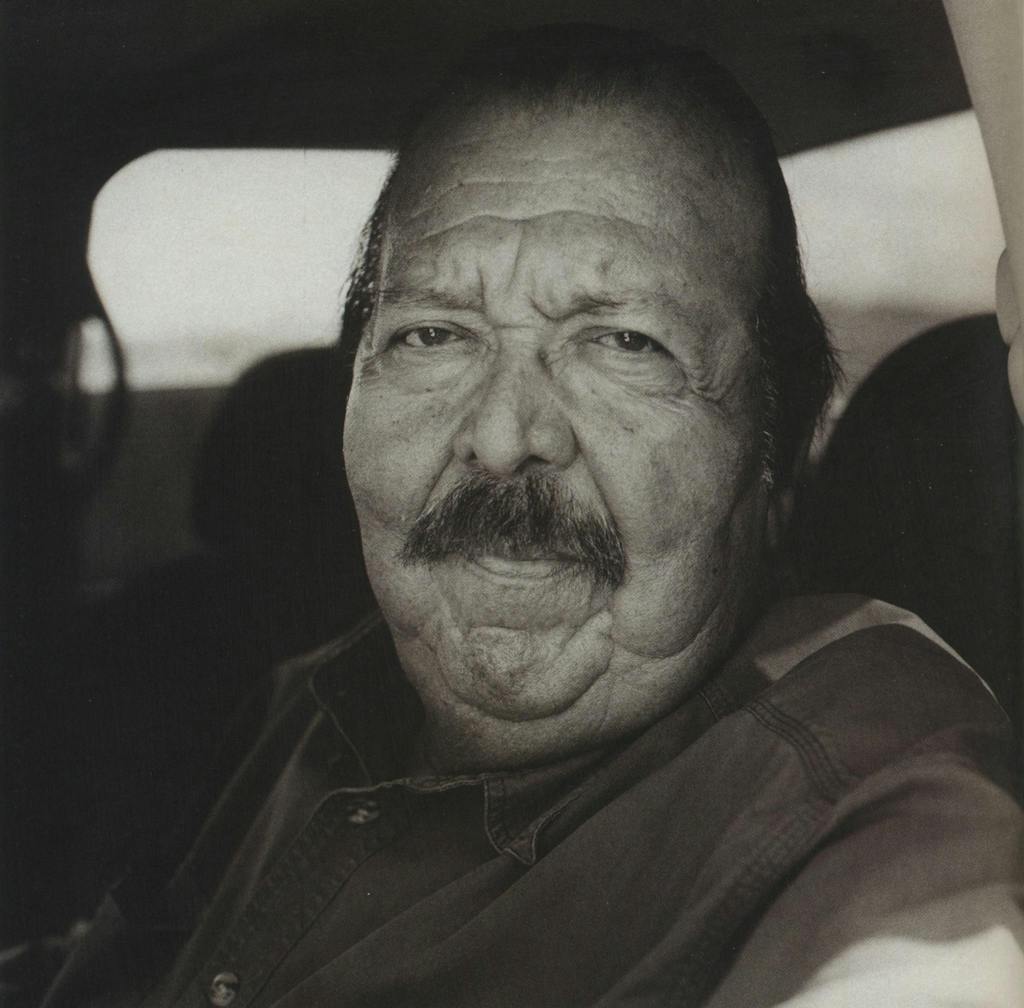

To the east, behind a series of locked gates on the Kenedy Ranch, is a cemetery where immigrants who have died while crossing this land are buried. I asked Rafael Cuellar Jr., the former Kenedy County sheriff, if he would take me there one afternoon in July. Cuellar, who stands six feet three, is known around town as Junior, and he has a hangdog face and a gentle, kindly manner. At 68, he is hard of hearing and his legs are crippled by diabetes; he shuffled out of the courthouse to meet me with the help of a cane. He had joined the sheriff’s department in 1978 and served as sheriff from 1990 to 2000, when this area became one of the deadliest passages for undocumented immigrants in the nation. “I think I found sixty dead, and I think I saved about the same,” Cuellar told me as we turned past a gate on the Kenedy Ranch, down a sandy, unpaved road that threaded through the salt grass. “The nineties is when they started dying on me. Before then, they used routes around the checkpoint that were closer to Highway 77. The more immigration officers who came down here, the farther from the highway they went. And the farther you get from the highway, the more dangerous it becomes.”

As sheriff of the fourth-least-populated county in the nation, Cuellar had coaxed stray cattle off the road and investigated oil field theft, but nearly all his work, in one way or another, involved undocumented immigrants. He and his deputies had to recover the dead. Bodies turned up all over the county, found by ranch hands, Border Patrol agents, hunting guides, and oil field workers. Some had been deceased for a few hours; others were only bones. There was the twelve-year-old boy whom Cuellar was never able to identify. The woman from Peru who died just a quarter mile from the highway. The man who was so overcome by the heat that he tore his clothes off before he died. Regardless of the season, the dead kept coming. “In the summer the sand is at least a hundred degrees, and they would walk in it until they couldn’t stand up anymore,” he said. “In the winter they would die from the cold. And when the temperature was normal, they would get hit by the train. They would sleep in between the tracks because they thought it would protect them from snakes. They would use the rail as their pillow, and we would have to pick up the pieces.”

Cuellar’s great-grandfather had come from Mexico in the late nineteenth century. His grandfather was a ranch hand on the Kenedy Ranch until he was eighty, and his father was a foreman there for fifty years. Cuellar, who had worked security on the ranch, used his familiarity with the land to help find the missing. “We would get anonymous calls from Corpus or Houston that someone in a group had been left behind,” he said. “They would give very general information, like, ‘She was by a windmill, two hours from the checkpoint.’ We had to look with bad information, but sometimes we got to them when there was still a chance to save them. Sometimes we couldn’t, and we’d find a skull three months later.” The dead were often arranged as reverential still lifes by a sibling or a friend who was with them at the end. Hands were folded across chests. Voter registration cards were laid out beside them. Crosses made from tree branches stood above them. Holy cards rested on their chests, the Virgin of Guadalupe clasping her hands in prayer over them. One woman dug her own sister’s grave, using a plastic jug she had cut in half and her bare hands.

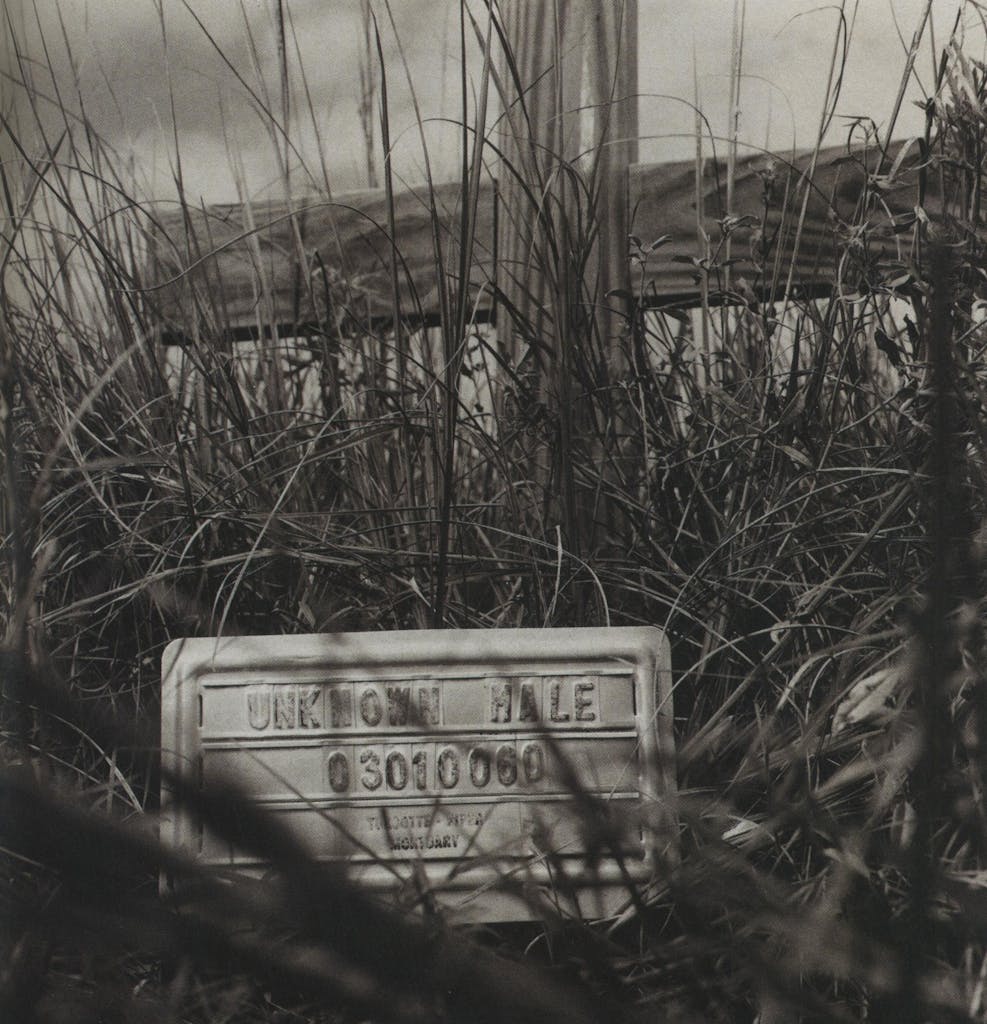

“I used to ask people why they would risk so much to come here,” Cuellar told me, as he turned down another sandy road, a long way from where we had started. “One man told me that his family was dying of hunger over there, and he could make enough money for food over here.” He handed me a set of old keys to unlock the last ranch gate. I swung it open, and he drove through. We were close to Baffin Bay, and thunderheads hung in the sky over it, to the east. The salt air was thick and humid. Cuellar steered his pickup past an old wire fence, into the cowboy cemetery where many of the Kenedy Ranch’s vaqueros and ranch hands have been laid to rest. It was a wild, shaggy place overgrown with sunflowers and grape vines. “My grandfather is buried over there,” Cuellar said, gesturing toward the section to the west where the old tombstones stood. “And over there,” he said, motioning to the east, “is where we bury the immigrants that can’t be identified or whose families never come for them.”

Thirty-four plain pine crosses stood on the east side of the cemetery. Aluminum markers, driven into the dirt in front of them, offered whatever meager information there was: “Unknown skeletal remains.” “John Doe.” “Unknown Male.” “Female Unknown.” The salt grass had grown high around the markers, and I had to kneel down and push back the undergrowth to read them. Cuellar stayed behind in his pickup, staring out at the paupers’ graves. As sheriff, he had made sure that the immigrants who were laid to rest here had received a proper burial, with a priest, if he could find one. The pallbearers were usually himself, his chief deputy, the mortician, and his assistant. “See the space right here, between the crosses?” he asked when I got back into the truck, pointing to a gap in one row. “We exhumed the body of a seventeen-year-old boy after we tracked down his family through the Mexican consulate. Eighteen or twenty years ago, he had run east from the checkpoint at night, and he got lost. I found his body a week later. He had fallen back on his legs, kneeling, and he died like that.”

Cuellar turned in his seat to look at the newest cross, beneath which grass had just started to grow. A long, empty space for future graves ran south of it to the cemetery fence. “There are going to be more crosses there by the end of the year,” Cuellar said. “That row is going to fill up, and we’ll have to start another. And there’s no way we can stop it, as long as they have nothing to eat over there.” He shook his head as he looked out at the pine crosses, and then the sky beyond it, which was growing dark. He turned the key in the ignition. “We should go,” he said. “The rain is coming.”

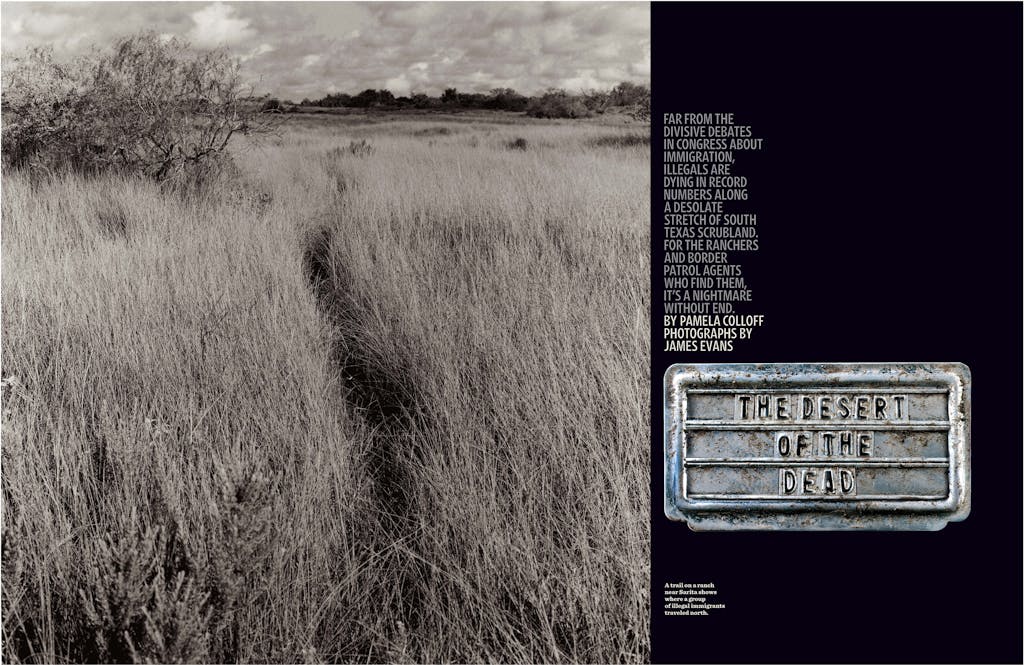

“LOOKS LIKE A LOT OF TRAFFIC went through here last night,” Strubhart told me one morning as he studied a patch of earth on the north side of Cielo de Cazadores de Codorniz. “I’d say it was a group of about twenty-five people. See the grass, how it’s flattened?” He was stooped over, inspecting an area by the side of the road that had caught his attention. The tall prairie grass lay at an angle, some of it flush with the ground. The trail continued on for a distance, as if a group of people had trampled through it single file.

“They funneled through here,” Strubhart said as we started to follow the path. “They must have been walking after the rain, and it rained yesterday at noon. See the dirt from their shoes? See how it sticks to each blade of grass? If they had passed through here before the rain, it would have washed the dirt off. They probably crossed late last night or early this morning.” We continued on until we had reached a mesquite thicket. “When they walk through this part of the ranch, they’re following the gas pipeline, over there,” he said. “It runs north from McAllen all the way to Chicago. It’s on all the coyotes’ maps.” He ducked under mesquite branches and followed the trail. “I’m guessing they took this little detour because they got spooked by something, or they were trying to avoid the sensors,” he said. “You know Immigration puts sensors in the ground so they can tell where illegals are walking?” He bent over to examine a sun-bleached jawbone with two prominent, pointy bottom teeth—“Javelina,” he announced—and then resumed his search, his eyes trained on the ground. “Looks like one person walked out here and checked that everything was clear, and the rest followed him back to the pipeline,” he said.

We continued the conversation back in his truck, and as we talked, he made his way through the property, eyeing the fence line to see where it needed fixing, stopping at each windmill to make sure that the trough beside it held plenty of water. Every now and then he spotted something that needed his attention, and he hopped out to tinker with a feeder or adjust a water pump. “The ranch is eight miles across, and there is a trail every mile or so,” he said. “The coyotes use different paths; it just depends where Immigration is putting pressure on them. When a group has to cross a caliche road, the last person wipes his footprints out with a branch. So I look to see if there are brush marks on the road.” He knew the terrain well enough that he could tell where they had been, not only by the plastic bags and water jugs and cast-off clothes they left behind but also by the way they altered the landscape. “I could tell you if someone had broken a limb off that tree, just like you’d notice if you came home and someone had moved a piece of furniture in your living room,” he said.

As Strubhart drove, he would stop occasionally to lift his binoculars; squinting into them, he would fall silent, studying the wildlife from a distance—a white-tailed buck, a flock of wild turkeys, a nilgai antelope. Cielo de Cazadores de Codorniz, which means “Quail Hunter’s Heaven,” is the private hunting preserve of a retired banking executive, and it falls to Strubhart and his ranch hands to keep its wildlife flourishing until deer season. Just as Strubhart keeps track of how many does are dropping fawns, so he notes the progress of immigrants through the ranch; as we talked, he stopped to pick up a blue oxford shirt that lay, incongruously, in the middle of the wilderness. “The largest group we ever had come through here was fifty-four people,” he said. “Usually it’s groups of twenty people, or five or six. Most groups have kids in them. We see a lot of pregnant women who want to give birth on this side of the river. I’ve seen mothers carrying infants that still had their umbilical cords.” Strubhart sighed and studied the road ahead. “Last week, I came across a group of twenty-two kids who were walking with a guide, and I called Immigration,” he said. “Not a one of them was older than fifteen.”

Dust kicked up behind Strubhart’s truck as we headed deeper into the ranch. “The coyotes have GPS systems, night-vision goggles, cell phones, hand-drawn maps,” he continued. “They’re professionals. They have scouts they send through this country. They watch when Immigration goes up and down the highway, and they know when the shift changes happen.” The mechanics of human trafficking, he explained, were as clever as they were mercenary, with a skilled coyote charging each undocumented immigrant anywhere from $1,200 to $1,500. Each coyote has a crew, he explained, and each crew has a driver who drops the group off in the brush somewhere south of the checkpoint. “You can see them at sunset—a whole carful of people bailing out into the brush,” he said. “Sometimes they leave the bail-out cars by the side of the road with the doors hanging open.” Another member of the crew takes them into the brush, Strubhart said, and guides them past the checkpoint to a predetermined spot. Then a driver picks them up by the side of the road and takes them to stash houses in cities farther north.

“The coyotes know how hard the trip is, but they paint a pretty picture for these people,” Strubhart said. “You can tell by what they’re carrying that they have no idea what they’re getting into. They’ll bring a toothbrush and toothpaste but no antibiotics, no soap, no clean clothes, nothing they can doctor themselves with. They wear cheap tennis shoes that fall apart. By the time we find them, they’re crawling with ticks. They’ve run out of water, so they’re drinking from the troughs. They’re carrying plastic jugs that are full of brown water.” Strubhart lit a cigarette and cracked his window open, slowly exhaling into the hot air outside. He looked tired in the morning light. “When I went to Vietnam, I saw real poverty,” he said. “Most people have no idea what it means to live in a place with no education, no opportunity. The Vietnamese had nowhere to go. Mexicans have somewhere to go, so they come here instead of making their own country better. And as long as they can find jobs here, they’ll keep coming. I’m not for or against them. It’s just hard seeing how much some of these people suffer.”

To prove how tough the journey is, Strubhart took me to a well-traveled area near a deer blind, a sandy slope studded with prickly pear and huisache, a few miles from the highway. “Try walking that little hill, just so you can see what it’s like,” Strubhart suggested, and I did. The sand was as loose and fine as sugar, and it shifted under my boots. Each step required effort, and after a few minutes, my legs started to ache. The air was thick and humid, and the heat was unbearable. “Imagine doing that for a couple of days with a twenty-pound sack on your back,” Strubhart said when I returned, short of breath. “They’ll get in this sand and it will spill into their shoes. Pretty soon they’ve got some unbelievable blisters. Then their feet get so swollen that they can’t get their shoes back on. We find people out here, barefoot. When they can’t walk anymore, the group leaves them behind.”

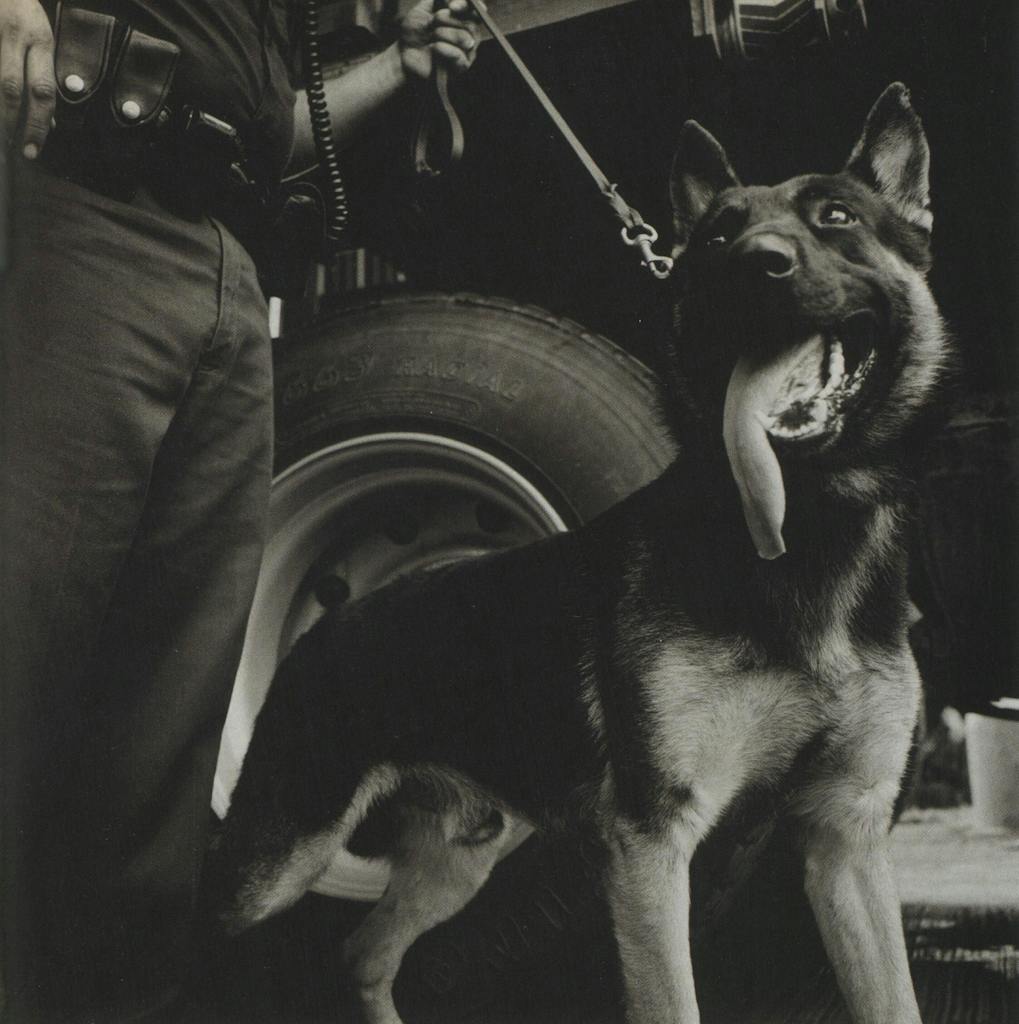

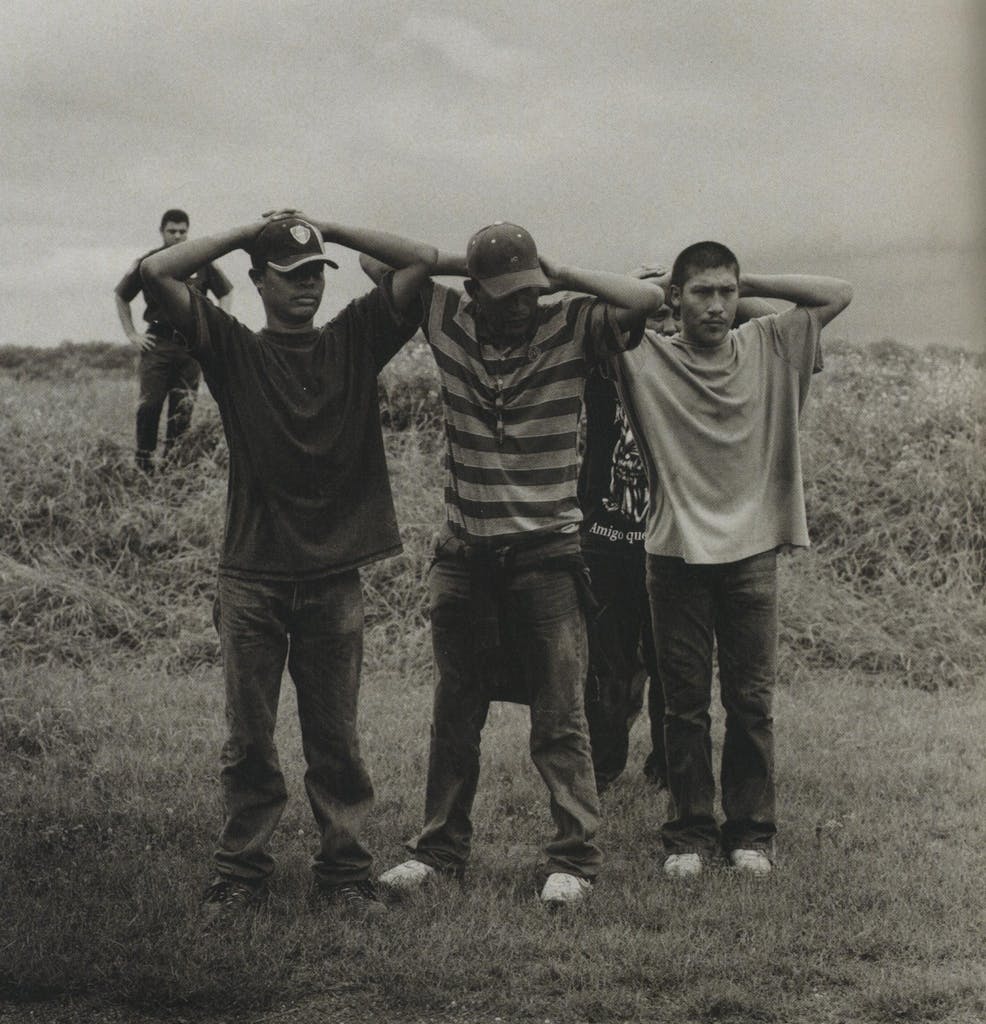

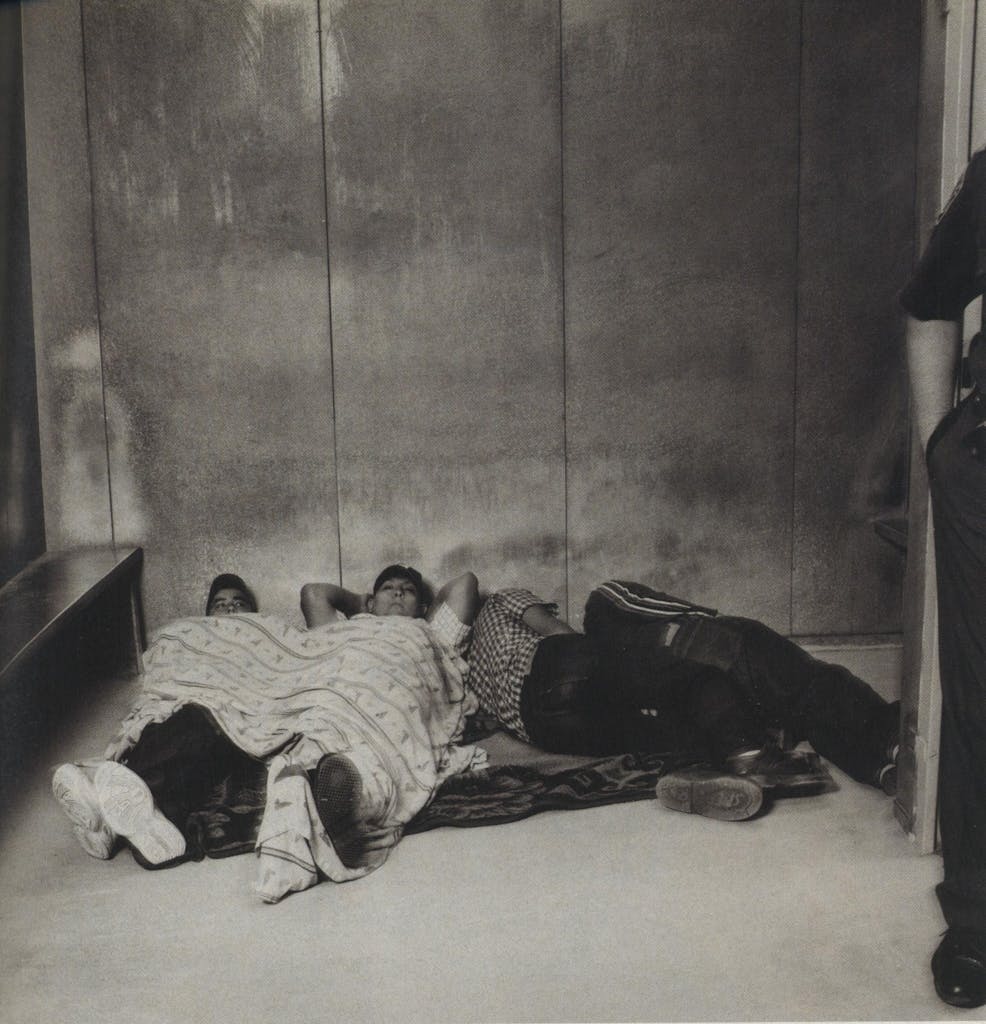

THE CHECKPOINT SOUTH OF SARITA, which I visited one morning in July, hardly looked like the kind of place that so much human drama revolves around. The traffic stop, demarcated by orange pylons, sits next to a brightly lit Border Patrol office, where three Mexican nationals waited for their paperwork to be processed. A line of cars trickled by. I watched as a succession of drivers—oil field workers, truckers, green card holders, college students returning from South Padre Island—was waved through, answering the question “Are you a U.S. citizen?” as a dog trained to sniff out contraband circled their vehicle. A few were pulled over for more-rigorous inspections, but it was a slow morning, and they yielded nothing. Most of what happens here takes place not at the checkpoint but around it, on the ranchland that extends beyond the highway. The Border Patrol deploys many of its agents out in the brush, where they track the movements of groups of undocumented immigrants using night-vision goggles, infrared scopes, and sensors and by “cutting sign,” or reading the ground for tracks. On busy days, agents apprehend hundreds of “brush walkers,” whom they bring to the checkpoint and question. More and more, though, it is the checkpoint 22 miles to the west, in Falfurrias, that is recording the greater number of undocumented immigrants. “If you want to see what’s really going on, go to Fal,” one Border Patrol agent advised.

There are only two major highways out of the Rio Grande Valley: U.S. 77, which runs north through Sarita, and U.S. 281, which runs north through Falfurrias. For the past few years, the Border Patrol has concentrated on slowing illegal crossings in Brownsville, and coyotes, in turn, have turned their attention west, ferrying more undocumented immigrants out of McAllen on 281. To get around the checkpoint, they have taken increasingly remote routes, and though apprehensions in the region have dropped, the number of deaths has soared. In the Border Patrol sector that includes Sarita and Falfurrias, 30 undocumented immigrants died crossing in 2002. In 2006 that number had shot up to 81. (The Border Patrol tracks fatalities by fiscal year, which runs from October to September.) This year alone there were 245 rescues, nearly double what there were in 2004. “There’s a lot more at stake now,” Agent J. J. Garcia told me at the Falfurrias checkpoint. “As the Border Patrol gets bigger, it becomes harder to cross the border. We have more cameras, more agents, more sensors in the ground. We’ve got the National Guard assisting us. By the time people get this far north, they have invested a lot of time and money in getting where they’re going. If they’re from El Salvador or Honduras, they may have been traveling for months. They’re going to do whatever it takes to get around the checkpoint.”

The Border Patrol has been so overwhelmed by the number of undocumented immigrants in medical distress that it has stationed its own search-and-rescue team in Falfurrias. “We’re trying to save lives, whether we’re apprehending people in the brush or treating them,” said Agent Alejandro Garcia, when I asked him whether his job as a medic worked at cross-purposes with the Border Patrol’s mission. “You don’t think about whether they’re illegal when they’re hurt; they’re human beings.” I was tagging along with Garcia and two of his colleagues, Isaac David and Jose Puebla, as they patrolled U.S. 281. Just over an hour passed before a call came across the radio about a rollover accident in a secluded stretch of ranchland twenty miles northwest of the checkpoint, on Texas Highway 339. The dispatcher reported that there were at least eight people in the Suburban and that two were believed to be dead. “We’re seeing more of these kinds of accidents,” David shouted over the roar of the Humvee as he steered us, at top speed, toward the scene. “It’s usually an older vehicle, and the shocks are worn. A smuggler is picking up a group that has walked through the brush, or dropping one off, and they’re in a rush to get out of there, so they’re driving too fast. No one is buckled in. When you hear numbers like that—eight adults in a Suburban, this far out—you can be pretty sure we’re talking about a group that is being smuggled.”

When we arrived at the scene, on the heels of a local EMS unit and the sheriff’s department, the accident was even worse than the dispatcher’s report had let on: Fourteen passengers had been riding in the Suburban, and all of them had been thrown. People lay in the grass on either side of the two-lane highway. Blankets had already been draped across the faces of the three who were dead. The Suburban was beached on its side, next to a frayed tire that had split open. Strewn across the pavement were empty water bottles and cans of Red Bull, sneakers and soiled clothes. One man sat in a daze as blood seeped from his forehead. The only sound was that of a woman moaning as EMTs struggled to stabilize her. David and Puebla ran to assist another young woman, whose legs were bent at odd angles; her right shin bone protruded from her skin, and her eyes were squeezed shut, as if she were concentrating on the pain. “¡Mis piernas!” (“My legs!”) she screamed when David wiggled her toes. The medics administered oxygen and an IV and tried to keep her calm. Her hair was dirty and matted; she hadn’t bathed in a long time. When David asked her when she had last eaten, she whispered that it had been three days.

A justice of the peace, an older man in a white straw hat, pulled on latex gloves and began to catalog the dead. A DPS investigator took photos. The injured were loaded into ambulances, including the woman David and Puebla were working on. Her lungs had begun to fill with fluid, and her blood pressure had dropped precipitously low. “I need to get her to a hospital, quick,” an ambulance driver said before peeling off. The injured woman, like several others in the group, had come from El Salvador. “These people had been walking for a long time,” said Alejandro Garcia, as we watched the ambulance race down the highway. “They did it the hard way. They walked all the way out here so we wouldn’t find them. They had made it. It all came down to a blown tire.”

EXCEPT FOR A TOUR OF VIETNAM that began in 1968, Donald Strubhart has never lived farther than the neighboring county, where he grew up on a dairy farm outside the town of Riviera. He was the oldest of thirteen kids, and Spanish was spoken often enough at home that he was the only Anglo placed in a remedial English class when he started elementary school. “I was twelve or thirteen before I saw an immigration officer,” he said. “In the fifties there were maybe two or three of them in all of Kleberg and Kenedy counties. There were more game wardens back then. Mexican nationals would come to our house tired and hungry. They would work for us for five or six days, and we would feed them and give them a place to stay. The women would wash clothes and help around the house. The men repaired water lines and fence lines; they would feed and milk the cows. They slept in the barn because that was all we had. Once they were fed and rested and back on their feet, they went north to make more money.”

Strubhart was drafted when he was nineteen, and he served as an Army Ranger with military intelligence, tracking the Vietcong through the jungle on long-range reconnaissance patrols. “Eighteen of us went, and three of us came back,” he said. He had been captured after being knocked out by a concussion grenade and was tortured until he was rescued, three days later, by his fellow Rangers. He returned home with seven Purple Hearts and no job prospects. He married Dee Deanda, a pretty brunette from the South Texas town of Agua Dulce who was a waitress at a local cafe, and after he had worked construction and cowboyed for a while, he started his own home-repair business. Strubhart loved to hunt and work outdoors, and the solitude of living on a ranch appealed to him. After he grew his repair business into a successful construction company, he left it behind to manage Cielo de Cazadores de Codorniz. He built the ranch house himself, out of cedar, and he and Dee moved to a more modest house next door.

At the time, Border Patrol initiatives in El Paso and San Diego were having some success, and traffic was shifting to more-desolate crossing points, which led north through places like Kenedy County. Strubhart was stranded in the middle, left to find the sick and the lost who stumbled out of the brush. The ones who were in the worst shape made their way to the house. “Dee and I came back from town a few years ago, and a thirteen-year-old girl—she didn’t weigh seventy pounds soaking wet—was lying in our driveway, next to the dogs,” Strubhart said. “She’d been lost out here for three days and three nights. She was scared to death; she couldn’t hardly breathe. She’d been drinking dirty water out of the troughs, and her clothes were torn and filthy. She was from El Salvador, and she was trying to get to her brothers who lived in North Carolina. Her daddy had sold some cattle so she could cross. It was raining, and she was shivering when we found her. We sat her down on the porch, and Dee put the girl’s head in her lap and tried to calm her down.”

Strubhart calls the Border Patrol whenever he sees undocumented immigrants passing through the ranch, and he is grateful for the help, but he is unsure what effect they have on the number of people crossing through the property. “When we go quail hunting, we have pointers—the best hunting dogs in the world—and they don’t find but twenty percent of the coveys,” he said. “And we know where the coveys are. Immigration has told me that they think they catch about ten percent of people coming through here.”

Dee keeps extra rosaries on hand to give to the occasional strangers who wander up her driveway so they can have a source of comfort when they are taken to the checkpoint. She shows them what kindness she can. “Last October an illegal was limping along the fence line,” she told me. “He was an older man from Mexico, I’d say in his mid-fifties. He was tired and his shoes were falling apart. He asked if it was okay if he could sit under that tree, in the shade. I fixed the man some sandwiches and tea. I gave him a pair of socks and an old pair of sneakers my son outgrew. Was that illegal? Should I not have helped him? A grown man had asked me for permission to sit in the shade. These things stay with you.”

What stays with Strubhart are the things that Dee never saw—the teenager who was eight months pregnant who lay in the dirt, abandoned by the group she had been traveling with. The woman he found cowering in the grass with an infant. The bodies he kept discovering. “I found an older man who died from a rattlesnake bite,” he said, when I asked him about the others, besides Ezequiel Amaya Escobar, he had come across. “There was a nineteen-year-old boy who had been dead for three days, who died from dehydration; I was by myself when I saw buzzards on him. I found another boy, who tried to cross the lake and drowned. He was floating on the shore. Six years ago I found a human skull. It wouldn’t surprise me if we found only half the people who’ve died out here. I’ve looked with Immigration for three bodies that illegals have told us about—people they say died out here—who we never found.”

IN SARITA I HEARD ABOUT Deyanira Gallegos Tapia, a 24-year-old undocumented immigrant who had lost her legs in a train accident near the ranch. A Univision reporter in McAllen named Victor Hugo Castillo had taken an interest in her case, and he put me in touch with her husband, who had made the journey with her and who was living in the Valley.

Alejandro Sedano Gutiérrez met me one afternoon in Weslaco, neatly dressed in a button-down shirt and slacks, his jet-black hair combed smooth against his forehead. Deyanira had gone to Mexico with her mother for an extended visit to see her family, he explained, but in her absence, he agreed to tell me her story. Deyanira had come from the village of Chignahuapan, near the industrial city of Puebla, Alejandro said, where she had supported herself and her six-year-old son by making Christmas ornaments for $18 a week. Her father, who was a police commander, had been murdered when she was a teenager. Alejandro and Deyanira had started dating when he came to Puebla to see relatives; he was already living in the U.S., washing dishes in a restaurant in Missouri. Deyanira’s half-brother, Andrés, had gone north as well and was living in Houston. Both men had slipped across the border years before without any problems. Andrés was visiting family in Puebla last spring, and when he and Alejandro were ready to head back to the U.S., Deyanira decided to join them. She asked her mother to look after her son, promising to come back for him once she had gotten settled up north.

On April 13, 2005, Alejandro said, they all took a bus to Reynosa. They paid a coyote $350 to drive them to the river and guide them across, paddling on a raft to the opposite bank when the coyote’s lookouts on the Texas side said it was safe. From there, they were loaded into a station wagon and driven to a motel in McAllen, where they waited for four nights. A coyote said she would take them to Houston for $1,500 apiece, and Alejandro helped pay Deyanira’s way with money he had saved washing dishes. “The coyote said she would drop us south of the Sarita checkpoint,” Alejandro told me in Spanish. “She told us we would walk around the checkpoint for four hours and then get picked up. Andrés never told us this was a different coyote than the one he had used before.” They were driven up U.S. 77 and let out along a dirt road by some railroad tracks. The coyote came with them. “She walked with us for about four hours,” he said. “She pointed at some lights and said that was the checkpoint. She said she would pick us up once we had walked around it, and she left at about two a.m.” By dawn, they knew they had been tricked; the lights were distant radio towers. “Andrés said, ‘The checkpoint shouldn’t be much farther,’” Alejandro explained. “He said, ‘Let’s keep walking.’”

And so they walked. “Five nights we were out there,” Alejandro said. “We would walk at night and sleep during the day. When we saw Immigration, we would hide under mesquite trees. We ran out of water the second day. Food was gone by the third. I had a map, but I couldn’t figure out where we were.” Only later did he understand that they had been dropped off in Raymondville, a full fifty miles south of Sarita—not the four-hour trip they had been promised. “We started drinking from the troughs,” Alejandro said. “The water had algae on it, but we were thirsty. At night, you could hear the coyotes howling.” They prayed for food, and on the fourth day, as if by divine intervention, they found two cans of beans, two cans of corn, and a can of mandarin oranges on the well-worn footpath they followed. On the fifth day, they saw a train that had slowed for long enough that they thought they could jump onto it, and they started to run toward it. “I grabbed onto the ladder on the side of the train,” Alejandro said. “Deyanira was next, but it sped up and her left hand slipped. The train started moving faster and she was knocked off balance. When I saw her falling, I jumped off. Both her legs were cut off. The train never stopped.”

Alejandro stared at the floor, and his shoulders sagged as he sat in silence. He pulled a worn piece of paper out of his pocket, reinforced with Scotch tape, that was beginning to come apart at the folds and handed it to me. At the top it read “You are an alien present in the United States who has not been admitted. … Notice to appear in removal proceedings under section 240 of the Immigration and Nationality Act.” He had a hearing soon, he explained, which would determine whether he would be able to stay in the U.S.; Deyanira was waiting to find out if she would be able to return at all. She was confined to a wheelchair and was dependent solely on her family. He had already received a hospital bill for $114,000, he said, which he was working to pay off. He had bought a twenty-year-old truck with pressure washers and had started a mobile car wash business that was making enough money to support them both—money he hoped to use to buy her prosthetics so she could walk again. “Deyanira tells me I can’t ask God why this happened, that we have to accept it,” Alejandro said. “We kept the can of oranges we found, as a reminder. It’s a sign that, as hard as things are for us, the hand of God is always there.”

“IF I GET UP AFTER THE SUN RISES, I feel like I missed the whole day,” Strubhart told me on my last visit to the ranch. “I like watching the world come alive.” We were facing the eastern sky, sitting on the back porch with his daughter, Melissa Webb, who is the ranch’s bookkeeper, and her seven-year-old, Lexy, waiting for the sun to come up. Strubhart had wanted me to see daybreak on the ranch before I headed home because it is the best time, he said, to be at Cielo de Cazadores de Codorniz. He was as cheerful and energized as I had seen him, though it was only six in the morning, and he stared out into the pitch-black wilderness as if he were awaiting a virtuoso performance. As the light started to break across the sky, he leaned forward in his chair so as not to miss a detail. “When the bobwhite quail mate in the spring, it’s like listening to a symphony,” he said.

The sky eased from black to gray. “Usually the coyotes are yelping and hollering and singing to each other by now,” Strubhart said. “I guess they must have gotten their stomachs full last night.” He dragged on a cigarette that glowed in the gloom. “Now you can hear the chicharros—the cicadas—getting started,” he said, as the silence gradually filled with a clattering sound. Strubhart handed me a pair of headphones that he used during hunting season when he worked as a guide. They had directional microphones that amplified sound, and through them, I could hear the cacophony of the ranch at dawn—or what seemed like each cicada, each feather that rustled, each twig that broke under the weight of a deer. “There’s a scissortail,” Strubhart said, pointing. “And a whistle duck … Do you hear the mourning doves? … That’s a female quail calling a male.” A doe ambled up to a feeder about fifty yards away, and then more deer began to emerge from the shadows, five of them in all. “You need to listen for when the turkeys come off the roost,” he said. “When they start squawking, they sound like a bunch of old ladies.”

The sky brightened, and ranch hands began turning their pickups into the drive. “Yesterday morning I drove down this road at daylight, and I saw where seven groups had crossed,” Strubhart said. “The smallest group had six in it and the largest had twenty-five. After a rain, you can really see their tracks. The first set of tracks were about four hundred yards from here. Then, at one mile, there were two groups. At two miles, two more. The farthest ones I saw were six miles in.” He pointed toward the headphones, which his granddaughter had placed over her ears and was listening to, enthralled. “I’ve been out here at night with those, listening for varmints, and I’ve heard people talking in Spanish,” Strubhart said. “They’ll be six hundred yards away, and you never can see them, but you can hear them talking.” He stared out into the ranch. Somewhere in the distance, people were making their way north.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Mexico

- Longreads

- Illegal Immigration

- Border Patrol