“The squawling [sic] kitten flopped into the pool. A big alligator lifted its jaws, closed like a vice, and the screaming cat was bitten in half. ‘There’s more to come, my pets!’ Big Joe Ball shouted, as the drunk-crazed crowd roared in appreciation. And he next tossed a puppy into the bloody pool!!”

—from a vertical file in the San Antonio Public Library

In the photograph Joe Ball pauses on a beach, wearing one of those old-fashioned bathing suits. His right hand grips an open whiskey bottle at his belly, as if between sips, and his left holds what appears to be a pair of binoculars. He’s standing barefoot in white sand next to weedy brush, like the kind that grows in the dunes along the Texas coast. He’s handsome in a roguish way and looks at the camera with either a squint or a sneer—it’s hard to tell which. If you didn’t know Joe Ball’s history, you might think he was just another old-time party boy, a genteel William Faulkner look-alike whooping it up. If, however, you’ve heard the legend of Joe Ball, his close-cropped hair and cramped face make him appear sordid, murderous. He looks like, on this day or one like it, he could get his girlfriend drunk, entice her to look off into the distance, shoot her in the head, bury her in the sand, and then return home to his bar, his waitresses, and his alligators. And that is just what Joe Ball did.

He was a bootlegger and a gambler, a scion of the richest family in tiny Elmendorf, about fifteen miles southeast of downtown San Antonio. He was, they say, a ladies’ man who had his way with the waitresses at his bar, and when they got pregnant, he got rid of them. Sometimes by alligator. When deputy sheriffs finally caught up with him, in September 1938, they dug up the dismembered corpse of one of his barmaids, dug up the girlfriend in the sand, and hauled away the gators. Ball became known as the Bluebeard of Texas, the Butcher of Elmendorf, and Alligator Man, and his story—told and retold in various newspapers, true-crime magazines, and books—caught the fancy of anyone who was ever fascinated by how low people could go, how much deeper the pit of human infamy could be dug. It was impossible to figure the final death count, so many women had come and gone through Ball’s doors over the years, but the total was at least five. Seven or eight. Twelve. Twenty. Twenty-five. This, it would seem, makes Joe Ball one of the first modern serial killers.

The facts in Ball’s story vary wildly with the source, from the number of victims to the names of the principals to what the witnesses saw. This is especially so online, where Web sites like the Wacky World of Murder and Homicidal Heroes treat Ball as if he were an early rock star, the Chuck Berry of serial killers. It’s almost as if they are rooting him on. Indeed, Ball is often hailed as mythic kin to Ed Gein, the Wisconsin weirdo who, in the fifties, killed people and dug up and flailed corpses and wore their skin—the guy on whom Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre were based. (It should come as no surprise that Hooper’s second movie, Eaten Alive, concerned a deranged Texas hotelier who fed his guests, including a pretty prostitute he hacked to death with a rake, to an alligator he kept in his yard.) Was Ball truly, as one site insisted, “one of the U.S.’s greatest nutcases”? Or was he, as other modern maniacs have defended themselves, merely misunderstood?

In San Antonio I found shades of the truth. Because the men from the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office who cornered Ball are dead, I asked their successors in an e-mail if any kind of written history of the department had survived from the thirties. No, replied a corporal there, but his great-grandfather had been the sheriff of neighboring Wilson County. “I heard Joe Ball was a black man,” he wrote, “and he would kill the waitresses and throw their bodies in a pond behind his place.” I went to the San Antonio Public Library and asked a librarian in the Texana-genealogy department if she had any files on the Ball family. She drew a blank until I said that the best-known member was a reputed serial killer. “Oh,” she said cheerfully, “this is the guy with the alligator farm?”

Well, not exactly, but close enough for a legend like Joe Ball’s. His tale is proof, once again, that people see what they want to see. Especially when it involves flesh-eating alligators.

Blink and you’ll miss Elmendorf, especially if you’re heading south on U.S. 181 and thinking about the beaches at Port Aransas or Corpus Christi. Most people speed right by the small town (population: 664) just outside the San Antonio city limits sign. If you turn west toward Elmendorf, you’ll drive through a couple of miles of scrubby fields, wide-open pastures, mobile homes, and mobile-home subdivisions. Many of the double-wides are nice, with tailored yards and pretty gardens. Their mailboxes reveal the town’s makeup: Garcia, Ramos, Guerrero. Elmendorf is about two thirds Hispanic, and it is pretty poor. Nobody ever photographed it for a tourist brochure. Many of the roads in town are gravel. The main intersection, at FM 327 and Third Avenue, has a stop sign and a hair salon. Just behind the intersection is a hand-drawn sign; on one side it advertises Tony’s Bar and Grill and on the other it shows a caricature of an alligator in a baseball cap with a bat on his shoulder that reads “Gators.” Nearby are Roy’s Place and DeLeon’s Grocery, which have been in business for seventy years. The Elmendorf Lounge used to be here, but now it’s out on 181.

The town was incorporated in 1963, and its first mayor was Raymond Ball, Joe’s brother. But it has had a troubled history of late. Elmendorf developed a reputation as a speed trap in the seventies, and in 1983 the mayor resigned, as did two successive police chiefs who were accused of submitting false documents to a state agency. In 1987 the mayor and a council member walked out of a meeting because of a disagreement; they resigned and later tried to come back, but the council wouldn’t let them. In 2000 the mayor and four council members, including Richard “Bucky” Ball Jr. (Joe’s nephew), were indicted for violating the Texas Open Meetings Act (a misdemeanor). The town got water lines laid only three years ago, and sewer lines are still in the works. Most of the commerce—restaurants, gas stations, antiques stores—is carried out on U.S. 181, which leads the rest of the world to pass Elmendorf by.

There’s plenty of action, though, at St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church, the largest and oldest church in town. Inside the parish hall on any weekday morning you’ll find a crowd of elderly people from the area, there to hang out with friends and eat a free lunch provided by the Texas Department on Aging and the City of San Antonio. On a good morning there are eighty, about half Mexican American, half Anglo. Some of the women start playing Mexican-train dominoes at ten-thirty; others spend their time visiting at the five lines of tables strung together cafeteria-style. The program has been going on since 1973. The first manager was a Mrs. Michael Ball.

I sat there for several mornings in the spring, pretending to understand Mexican-train dominoes and asking the seniors about Joe Ball. Everyone here knows the name; some actually remember the man. Lawrence Liedecke was fourteen in 1938. He used to sneak into Ball’s yard to see the gators. He said Ball was a good shot and that he could shoot a bullet through the mouth of a beer bottle or hit a coin in the air. But he was mean. “We were afraid of him,” remembered Pollie Merian, who is 88 years old. “He’d get mad and kill you.” Townspeople were suspicious of Ball even before his death, she said. “He was a dirty rat. He had some black people there; he treated them so mean.”

Locals take a certain hushed pleasure in talking about the town’s most infamous son, even if they don’t always get the facts right. “They found two bodies on the beach somewhere,” said Jesse Bayer, who lives in nearby Floresville. “But they never found any other bodies. He fed them to the alligators, what I hear. I don’t know how many.” I asked Alex Saucedo, who also grew up in Floresville, if he thought Ball had fed his waitresses to his gators. “Oh, yeah!” he said brightly. Someone at the table said it was a matter of the women all being whores, disappearing, moving on like whores do. I nodded, pretending to understand. Ultimately, Liedecke is skeptical about the bloody body count. “Too many liars,” he said. “I think there really were two.” But nobody knows for sure? He shrugged. “Oh, yeah.”

I walked outside to the large graveyard, where most of the headstones were decorated with colorful flowers. I thought Joe Ball’s grave would be off in some corner, hidden by neglect. But his is the first grave you see when you walk in the gate from the church: “Joseph D. Ball, Jan. 7, 1896–Sept. 24, 1938.” He’s next to his father, Frank X. Ball. Balls lie all over this cemetery.

Frank X. Ball built Elmendorf, which had been established in 1885 by Henry Elmendorf, who would later become the mayor of San Antonio. This was cotton country, and Ball borrowed some money and built a gin to process the crop. The railroad put a depot in town, and Elmendorf cotton—as well as pottery, bricks, and tile made at a local factory—was exported to the rest of the world. A school opened in 1902. By the late twenties the town was thriving, with general stores, a hotel, a doctor’s office, meat markets, a confectionery, and a couple of cotton gins. “My daddy said there’d be cotton wagons two miles up the old highway,” remembered Bucky, whose father, Richard, was Joe’s brother. “Elmendorf was a jumping town way back then.”

And Frank Ball was rich. He began buying and selling farms, especially when they got cheap during the Depression. He opened a general store, from which he sold everything from caskets to shoes. He built the first stone home in the area, and he and his wife, Elizabeth, had eight children, many of whom became pillars of the community. Frank Junior became a school trustee in 1914. Raymond opened a new grocery store, which also held the post office; his wife, Jane, would become the postmaster.

Their second child, Joe, was no politician. He was, however, good with guns. “My uncle could shoot a bird off a telephone line with a pistol from the bumper of his Model A Ford,” Bucky said. Ball joined the Army in 1917 to fight in the Great War. In his official Army photo he looks pale and innocent, as a lot of Americans did who went off to fight for democracy. Ball saw action in Europe, according to Bucky, received his honorable discharge in 1919, and returned to Elmendorf.

Joe may not have followed in his father’s footsteps, but he learned something from him about business. Just as people needed a gin to process their cotton, they needed, well, gin. And whiskey and beer. As Prohibition settled in during the twenties, Ball became a bootlegger. “He drove all around the area,” said Liedecke, “selling whiskey to people out of a big fifty-gallon barrel.” Ball was about six feet tall and 160 pounds, according to Elton Cude Jr., whose father, a Bexar County deputy sheriff, helped investigate Ball and later wrote about him in a book titled The Wild and Free Dukedom of Bexar. “He wasn’t near as good-looking as they describe in those detective magazines,” said Cude Jr. “He could be dangerous.” In the mid-twenties Ball began hiring, off and on, a young black man named Clifton Wheeler to help around the house and the business. Wheeler was a handyman, but he did a lot of Ball’s manual labor and dirty work. According to many, Wheeler lived in fear of Ball. Liedecke says that Ball would shoot at Wheeler’s feet to make him dance the jitterbug. As expected, Ball’s nephew has a different image of Joe based on the stories his father told him. “He was always kindhearted,” Bucky told me, remembering a tale about his uncle paying for a poor Mexican American couple to go to the doctor to have their baby. “He did things like that a lot of times.”

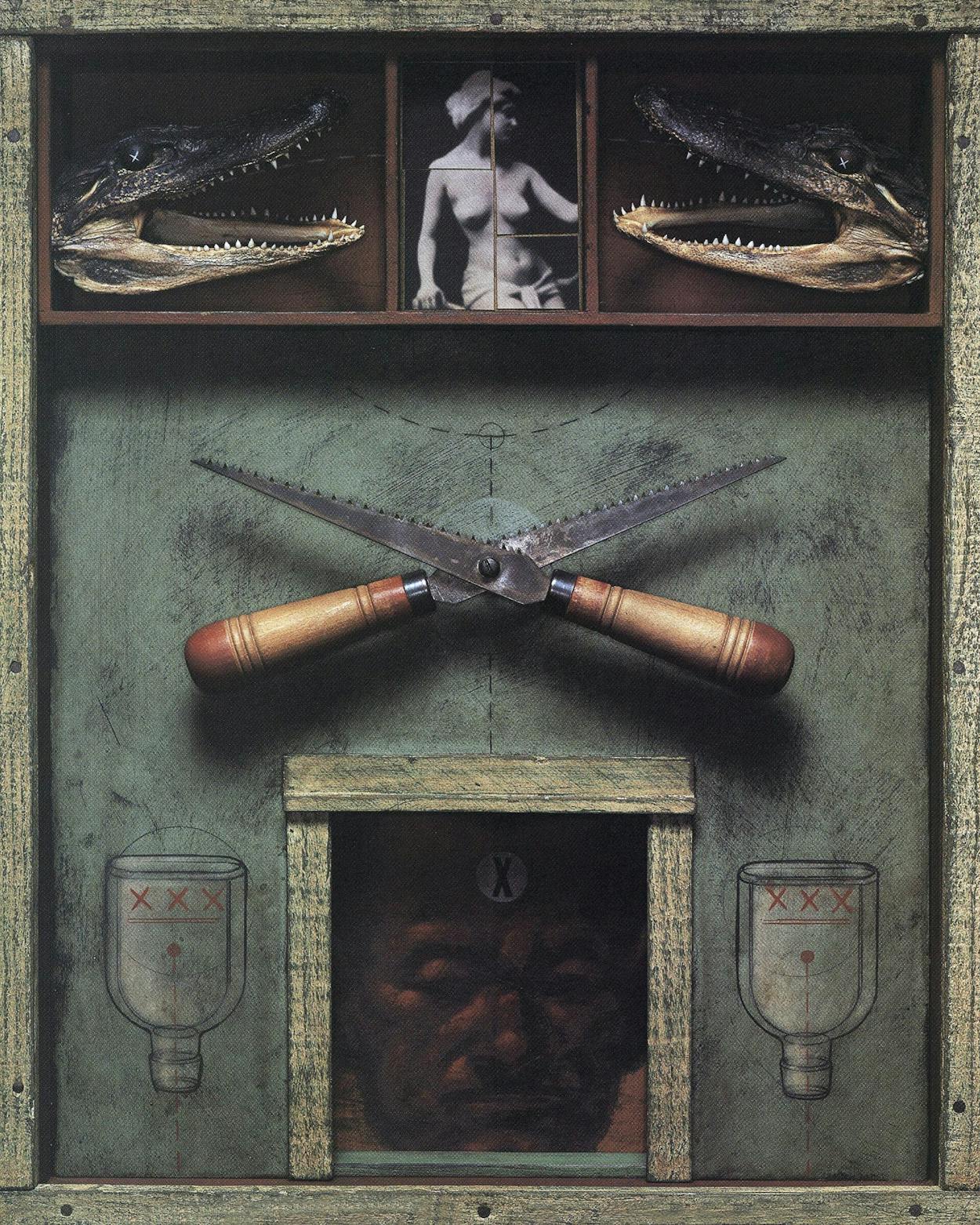

After Prohibition, Ball opened a tavern. In the back were two bedrooms and up front was a bar, a player piano, and a room with tables, where the men drank and played cards. Sometimes Ball hosted cockfights. At some point he went to one of the nearby low-water areas where alligators were occasionally seen, caught some, and put them in a concrete pool behind the tavern. He strung wire ten feet high around the pool. Perhaps he loved alligators, or perhaps he just knew how to bring in customers. “It was common knowledge that every Saturday night a drunken orgy occurred. . . .” wrote Cude in his book. “Any wild animal, possum, cat, dog, or any other animal without an owner helped make the show a little better. Get drunk, throw an animal in and watch the alligators.” Ball hired women, dance-hall girls, to wait tables. It was the Depression, hard times, and women came through Elmendorf, looking for work. Some stayed, and some just seemed to disappear.

Hazel Brown stares straight into your eyes. She is all confidence and dangerous beauty and looks like one of those hard-bitten starlets in Hollywood in the forties, like Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia, whose gruesome 1947 murder was never solved. Maybe it’s just the age of the photo or the era in which it was shot. It’s easy to see how Joe Ball fell in love with her.

Before her, Ball had fallen for other waitresses. In 1934 or so he met a woman from Seguin named Minnie Gotthardt, also known as Big Minnie. Big Minnie was, according to Cude, “a bossy, displeasing, and obnoxious person.” But Ball liked her—she ran the bar with him and Wheeler and had no fear of the drunks. At some point, though, Ball began seeing barmaid Dolores “Buddy” Goodwin, who was fifteen years his junior. She fell in love with him, even after one night in the spring of 1937 when he threw a bottle and hit her in the face, giving her a scar that ran from her eye to her neck. By then Brown, who was from McDade and known as Schatzie, was working at Ball’s. She was also young, only 22, and popular with the customers. She and Buddy became friends. Big Minnie, though, didn’t like Buddy one bit and wasn’t afraid to show it.

That summer, Big Minnie disappeared. Ball told people that she was pregnant in a Corpus Christi hospital; Wheeler heard Ball tell someone she was going to have a “nigger” baby. She must have skipped town in a big hurry, though, because she left all of her clothes behind. In September Ball married Buddy, and he revealed to her his secret, that he had taken Minnie to the beach and killed her. She wouldn’t make any more trouble for them. Buddy told Schatzie about Minnie’s demise. She told her a couple of times. In January 1938 Buddy’s left arm was cut off and stories flew around Elmendorf that Ball’s crazed alligators had torn it off or that Ball had cut it off and fed it to them. (In fact Buddy had lost the arm in a car wreck.) In April Buddy disappeared. By then Joe was seeing Schatzie. And then she disappeared too.

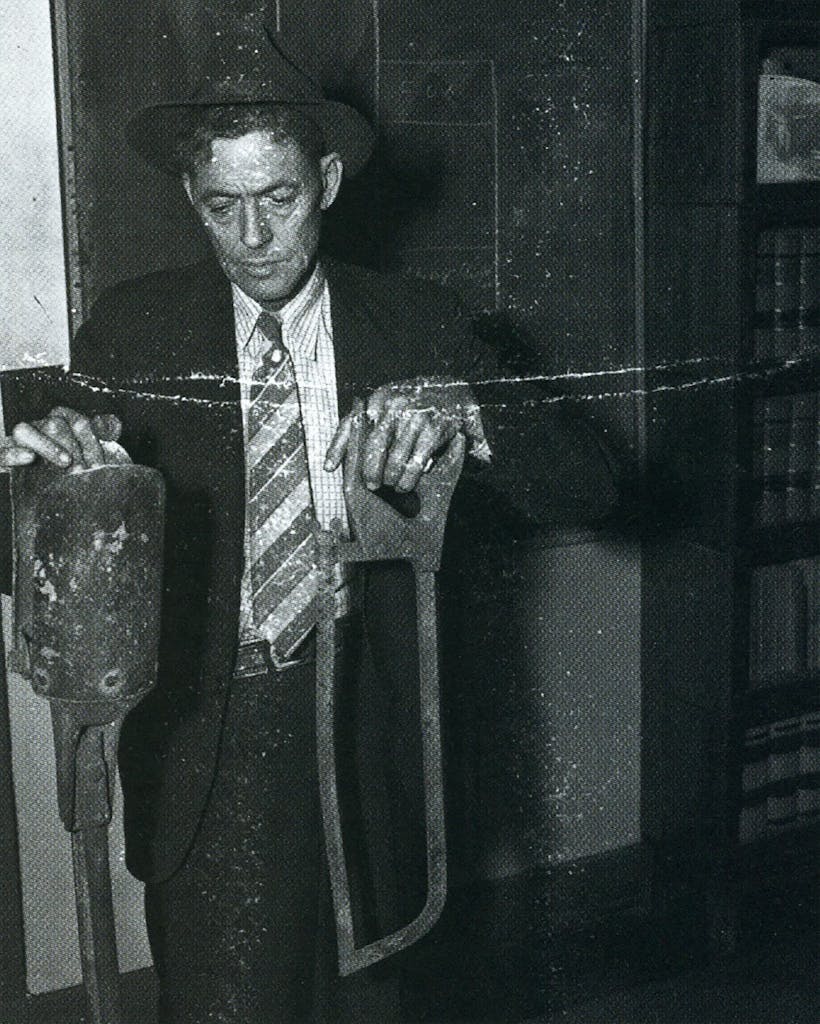

On September 23, 1938, an old Mexican American man approached Bexar County deputy sheriff John Gray, who was dove hunting in Elmendorf, and told him about a foul-smelling barrel covered in flies that Joe Ball had left behind his sister’s barn. It smelled, he said, like something dead was inside. Enough women in Ball’s world had disappeared that the next day Gray and deputy John Klevenhagen drove out to talk to him. Klevenhagen, who would later become a Texas Ranger, was a hunting buddy of Ball’s; he was as good a shot too. They went to the barn, but the stinky barrel was gone. They drove to the bar about noon and talked to Ball, who denied knowing anything about it. But when they all returned to the barn, his sister corroborated the old man’s story. That was enough for the deputies, who told Ball they were taking him to San Antonio for questioning. Ball asked if he could first be allowed to have a beer and close down his place. The sheriffs agreed, and the trio returned to the bar. Ball got a beer, took a few sips, went to his register, opened it, and then pulled out a .45 from under the counter. He waved it at Gray and Klevenhagen, who yelled, “Don’t!” and went for his own pistol just as Ball turned his and pointed it at his heart. He pulled the trigger and fell dead on the barroom floor.

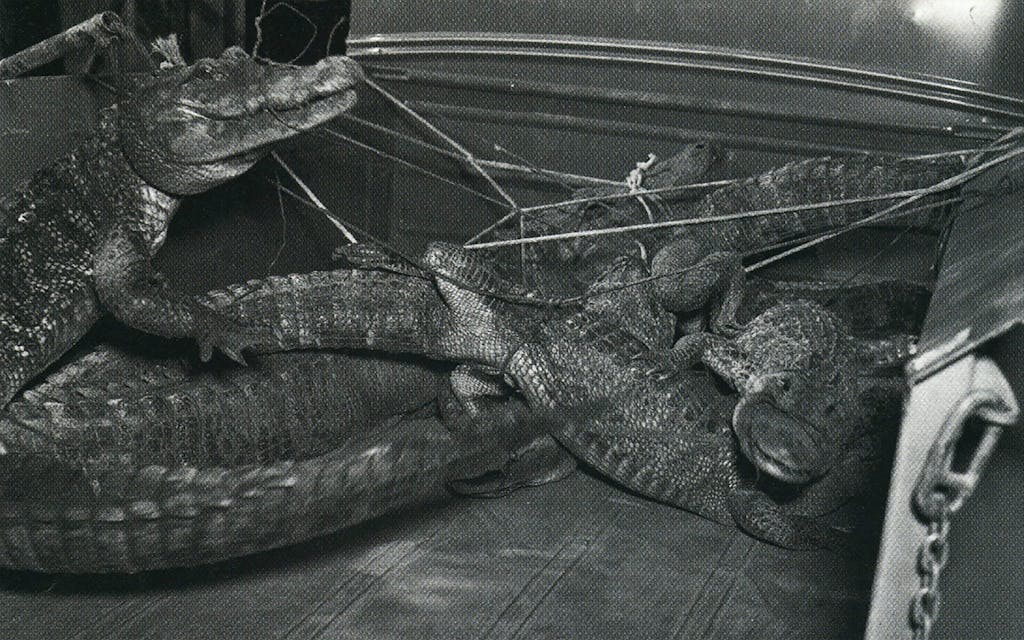

Four other deputies, including Cude, descended on the tavern. They checked the five gators (one large and four small) in their pond, which was surrounded by rotting meat. They found an ax matted with blood and hair. Their first theory was an obvious one, that the fearsome drunk had killed and mutilated his wife and other victims and fed them to the alligators. The cops talked about other disappearances, including two missing barmaids and a sixteen-year-old boy who hung out at Joe’s. Perhaps the Saturday night feeding frenzies had just been a cover for Sunday night murders. Maybe the old bootlegging barrels now held alligator food.

But then Wheeler, who had been taken by sheriffs to San Antonio, spilled the beans. Schatzie had fallen for someone else, he said, one of the bar’s customers, a guy with a home and a good job. She wanted out, but Ball wouldn’t hear of it. When she threatened to tell the police about Big Minnie, he killed her. And now the handyman knew exactly where Schatzie was. He took the sheriffs back to Elmendorf, about three miles from town, on a bluff some three hundred feet from the San Antonio River. By the light of a campfire, he began to dig. Blood bubbled up in the dirt, and the odor became unbearable. Wheeler pulled up two arms and two legs and finally a torso. The sight and smell were so bad, wrote Cude, “the sightseers ran in all directions and started heaving and up-chuking [sic].” Wheeler was asked where the head was, and he pointed to the remains of another campfire. After careful sifting, cops found a jawbone, some teeth, and finally some pieces of the skull that had once held the pretty face of Hazel Brown.

Wheeler told how, after a night of heavy drinking, Ball had asked him to load up the car with blankets and beer; Joe had a saw, an ax, and a posthole digger with him, as well as his pistol. They went to his sister’s barn, stopping along the way to drink, and then picked up the fetid 55-gallon iron barrel, which they took to the river. Ball forced Wheeler at gunpoint to dig a grave, and they opened the barrel. Out came Brown’s body. Wheeler refused to help Ball dismember the corpse, so he tried to do it himself. But he got so enraged when one of her hands got in the way of sawing off her head that Wheeler reached over and held Brown’s hand, and then helped further, holding her arms and legs while his boss sawed. They each got sick to their stomachs, so they drank some more beer and then buried the corpse, though they threw the head, as well as her clothes, on a campfire. As dawn broke, they sat around and drank beer and then drove back to the bar.

Wheeler also solved the mystery of Big Minnie. The previous June, Ball told Wheeler to pack the Model A Coupe and be sure to stow plenty of whiskey and beer. Then he took Minnie and Wheeler to Ingleside, near Corpus Christi. Ball found a secluded area and, after a little swimming and a lot of drinking, asked the doomed Minnie to take her clothes off. Wheeler made himself scarce, but when Ball called for more whiskey, Wheeler noticed that his boss had his pistol by his side. Ball pointed off in the distance, and when Minnie turned her head to look, he shot her in the temple. Wheeler was shocked, but Ball told him he had no choice—she was pregnant and he was seeing Buddy. The two buried her in the sand and drove back to Elmendorf.

Police officers questioned Wheeler about other women, and they found a packet of letters as well as a scrapbook with photos of dozens of women. This, said chief deputy sheriff J. W. Davis, “might lead to the discovery of one or a dozen more murders.” The San Antonio papers wrote of the disappearance of more than a dozen barmaids, including “Stella,” who had had a fight with Ball about Big Minnie. The sheriffs also had a theory that Ball was dealing narcotics and that it would have been a “simple matter” to put the dope in bottles and store it in the gators’ lair. They drained the pool but found no drugs.

Three days after Ball’s suicide, the police began digging in the sand four miles southeast of Ingleside. They took heavy machinery and hired local laborers, and people with nothing better to do—sometimes hundreds of them—came and watched. A local merchant set up a stand and began selling cold drinks. The crowds swelled. “Excitement and rumors ran high,” reported the San Antonio Light: Other dunes looked suspiciously like burial mounds and mysterious shapes were seen walking around at night. Finally, on October 14, they found the remains of Big Minnie, well-preserved in the deep, cold sand.

Meanwhile, the police had located Buddy in San Diego, where she had fled from her husband and gone to be with her sister. Two weeks later Klevenhagen and Gray brought her to San Antonio. On the way they stopped in Phoenix and found one of the women listed as “missing” from the tavern. Buddy later said that Wheeler told her that on her last night on earth, Schatzie, who didn’t know Buddy was in San Diego, had accused Ball of killing her, just as he had killed Big Minnie. Schatzie badgered Ball until he flew into a rage. “After a while,” said Buddy, “Joe hit her with his pistol, and I reckon that killed her.” He shot her too, just to make sure.

In the aftermath, the alligators went to the San Antonio Zoo, and Wheeler received two years in jail as an accessory. He got out and opened his own bar in town but soon left and was never heard from again. And Joe Ball’s legend bloomed. The pulp press had a lot to do with it. True Detective, the monthly bible of sordid true crime, found his story irresistible and wouldn’t let it go, returning often to the sensational tale of the murderous ladies’ man, dozens of hapless ladies, unborn children, mutilation, kitties and puppies, and of course, alligators starved for human flesh. Hungry gators sold magazines, just as Ball had used them to sell beer, but the facts in the stories sometimes came from the writer’s imagination. Elton Cude Jr. said, “My father called them once and asked, ‘Where’d you get those stories?’ According to one story, my dad was the roughest, toughest manhandling deputy sheriff in Bexar County history. Well, he wasn’t like that, though he did throw some drunks out of a bar occasionally.” Bucky told me about his aunt Madeline, Joe’s sister, who sued True Detective several times for their imaginative versions of Uncle Joe. “I don’t know if she ever collected,” he said. “She didn’t need the money.”

Other pulp magazines picked up the distorted story and so did books like The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers and America’s Most Vicious Criminals. Eventually the tale made its way to Web sites, where anyone can write history. So the hype kept building and the mistakes repeating: how Ball shot himself in the head, how his handyman was named Wilfred Sneed, how Sneed said that he had cut up twenty women, how chunks of human flesh were found in the pool. In retrospect, it’s hard to tell whom to trust. For example, according to a 1938 article in something called the Sheriff’s Association Magazine, that mysterious packet of letters found by the police contained one from Big Minnie telling Ball, “I am still willing to break up you and Buddy, if it is the last thing I do . . . Uncle Henry and I are going to take you to jail as soon as he gets here. I am going to testify as to what I know . . .” About what? Bodies? Gators?

There were plenty of other tales too, including the oft-told one of an old man who, in 1932, had stumbled onto Ball pitching a woman’s body into the pool. According to local lore, Ball threatened the man into leaving town; he fled to California and returned only after Ball was dead. Others claimed to have seen Ball throwing pieces of human flesh into the pit. Ultimately, of course, it’s impossible to prove he didn’t. Even though most of the “missing” women were accounted for (usually in San Antonio), some never were. And even though no human remains were found in the alligator pond, that didn’t mean Ball didn’t clean them up. And even though Wheeler, the only eyewitness to Ball’s crimes, never said anything about the alligators, that didn’t mean he didn’t know how to keep his mouth shut when he had to. With Ball, it was easy to believe the worst. It still is. Take one violent, sadistic drunk known for throwing stray pets to his alligators, add a one-armed missing wife, one hacked-up girlfriend and another buried in the sand, who knows how many stray women coming and going—you do the math. Six, ten, a dozen, two dozen barmaids hacked up. Gator food.

Buddy tried to set the record straight in a 1957 interview. “Joe never put no people in that alligator tank,” she said. “Joe wouldn’t do a thing like that. He wasn’t no horrible monster . . . Joe was a sweet, kind, good man, and he never hurt nobody unless he was driven to it.” Referring to the scar on her face, she said, “He didn’t even mean to cut me. He was throwing the bottle at another guy.” There were just two murders, she said. Elton Cude Jr. agrees, as did his father, who in a 1988 interview said, “I don’t think those alligators ate a human body of any kind.”

Bucky, of course, agrees too. Contrary to expectations, he has a sense of humor about the tale that has blackened his family name. Truthfully, he has no choice. When Bucky was training with the Green Berets in North Carolina in 1959, a friend’s mother, who lived in New Jersey and knew his last name, sent her son a comic book that told the horrifying tale of Joe Ball and the alligators. Bucky, who at seventy wears a jet-black pompadour and looks like an old rockabilly, chuckled as he remembered their shock when he said, “That was my uncle.” In April Bucky and his wife, who barrel race in their spare time, were in Giddings. “This friend of mine saw me and said, ‘Hey, Ball, did you bring your alligator with you?’ ” In truth, alligators aren’t that unusual in this part of South Texas, said Bucky, who remembers a stuffed one in the Floresville courthouse when he was a kid. “They get in the San Antonio River,” he told me. “I saw four over in Braunig Lake recently. They like that still water.” Bucky said his uncle probably got his from around Graytown, about three miles from Elmendorf, in the lowlands, where they go to lay eggs.

Bucky has his uncle’s World War I portrait and a 48-star flag given to the family after his death. He keeps them in a glass case in his living room. The 24-year veteran goes to counseling at Brook Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston and thinks his uncle’s experience in the war had something to do with his actions afterward. “My dad told me that after my uncle came back from the war, he was different. I guess what you see and do comes back to you. My counselor tells me your brain’s like a tape, and this stuff is on your brain. It’ll never go away.”

There wasn’t much Army counseling during the Depression, and Joe Ball probably wouldn’t have taken it anyway. He didn’t seem to be the type to talk about his feelings. Or maybe that’s just the myth talking.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Crime

- San Antonio