Do you know what happens to a human body in the desert? If it’s fresh, the intestines eat themselves out. The body swells, the lungs ooze fluids through the nostrils and mouth, and the decaying organs let out a cocktail of nauseating gases. Sometimes, scavengers leave their mark: a gnawed leg, a missing shoulder. Eventually, all that is left is a pile of white bones. But there is a cruel trick the dry weather will sometimes play on a corpse. It will dehydrate the skin before the bacteria can get to it, producing a mummy—a blackened girl with skin dry as cardboard, baring her teeth like a frightened animal.

In February 1996 a seventeen-year-old girl named María Guadalupe del Río Vázquez went shopping in downtown Ciudad Juárez and vanished into thin air. Days later, her body was found in the desolate mountains of the Chihuahuan Desert—raped, strangled, her left breast mutilated. As girls continued to disappear, residents of the city formed bands and scoured the mountains for more bodies. The state police picked up the corpses—seventeen in all, an epidemic of murder—and quickly scurried away, leaving behind clothing, locks of hair, shoes curled like orange peels. The girls’ hands were bound with their own shoelaces. All of the victims resembled each other: pretty, slim, medium to dark skin, long, straight dark hair. In a country that privileges men, whiteness, and wealth, these victims were female, brown, and poor. In a city that resents immigration and anything else from central and southern Mexico, these young women who had come to the northern border hoping to find work were social outcasts, strangers without names—especially now that they lay in silence in the sand, looking just like the ones before and the ones who would follow.

The deaths in the mountainous desert region known as Lomas de Poleo confirmed the worst fears of the women of Juárez: that something sinister had overcome their city. Beginning in 1993, there had been an unusual number of news reports in Juárez about the abduction and murder of women, an anomaly in Mexico. The grisly discoveries in the desert signaled that the worst crime wave in modern Mexican history had entered a new and more intense phase. Today, the toll of women who have been murdered in the past ten years is more than three hundred, staining the reputation of the country’s fourth-largest city worldwide. Some of the women were murdered by their husbands and boyfriends. Other killings seemed to be random acts of violence. Around a third of the victims, however, were teenage girls whose deaths appear to be connected to a cryptic and chilling kind of serial killing. This crime is indisputably solvable: Evidence has been scattered like bread crumbs all over the crime scenes, but the state authorities have jailed no one who truly seems responsible. Be it incompetence or a cover-up, the lack of credible prosecution in these cases is perhaps the most blatant—and certainly the most baffling—illustration of the nearly flawless record of impunity that characterizes the Mexican justice system.

Who would commit such crimes? Juárez brims with rumor and suspicion. A serial killer with government protection is an obvious possibility. The indifference of the authorities charged with investigating the murders has focused suspicion on themselves. Maybe it’s the Juárez police, some people say. They drive those white pickups with the campers, where they could easily hide a rotting body or a pile of bones, and they’re always prowling around the shantytown of Anapra, on the edge of the desert, peering out their windows. The Chihuahua state police zoom about in sleek, unmarked SUVs capable of navigating the rugged desert terrain. Recently, federal investigators speculated that fourteen of the killings might be linked to an organ-smuggling ring.

Or maybe it’s the drug dealers. The desert is, after all, their country, a frontier on the fringe of globalization. Between dips in the mountains, you glimpse El Paso to the north, its downtown towers gleaming like teeth. The Rio Grande cut through the mountains and created a valley that would in time birth the most densely populated border region in the world. But in Lomas de Poleo, there is only the sand and the desert scrub and a sea of trash—empty jugs, shabby toys, broken toilets, an unwound cassette of English lessons, plastic bags clinging to the brush like confetti. A frail man picks his way through a dumpster. An occasional small truck rattles off into the distance. They say that at night, this becomes the realm of gang members and drug runners, an army of men hauling their illicit goods into the United States. Rumor has it that if you wander far enough into the disorienting maze of primitive roads that have been scratched out of the sand, you will come upon a crude runway and a marvelous ranch with a swimming pool. If anybody sees you there, you should say you got lost and quickly turn around.

The obvious questions—who, why, how—remain unanswered. The abductions occur in mysterious moments, in quick, ghastly twists of fate that nobody seems—or at least wants to admit—to have witnessed. Most recently, they have transpired in the heart of the city in broad daylight. Some people believe the girls are taken by force, while others think it is more likely that the victims are lured by a seemingly innocent offer. A few mothers have said that their daughters disappeared a day or two after being approached about a job. Only one thing can be said with certainty, and it’s that in Juárez, Mexico, the most barbarous things are possible.

The sun shimmers over downtown Juárez like white linen, but I have learned to march down its streets staring at the ground or ahead with icy, distant eyes. To do anything else is to acknowledge the lusty stares from men of all ages who stand at the corners of the city’s busy thoroughfares waiting for nothing to happen. So begins the taunting. A skinny man with red eyes lets out a slow whistle through clenched teeth. Two young boys look at me, look at each other, and nod with a dirty grin. From among a group of men huddled on the steps of a shop, one calls out, “¡Una como esa!”—One like her!—and the rest burst out laughing, their mustaches spreading gleefully across their faces as they watch me walk by. This is everywhere in urban Mexico, I remind myself, but knowing what I do about the fate of women in Juárez, their glares begin to feel more predatory. I watch my feet skitter on the pavement and, with every step, wish I could shed these hips, this chest, this hair. To walk through downtown Juárez is to know and deeply regret that you are a young woman.

If not one case has been resolved in ten years, only two explanations are possible: Law enforcement is either inept or corrupt.

Juárez, though, is a city of young women. They run its shops; they keep its hundreds of factories humming. In 1964 the United States terminated the Bracero guest-worker program with Mexico and deported many of its laborers, dumping thousands of men along the Mexican side of the border. In an effort to reemploy them, the Mexican government launched the Border Industrialization Program, which prodded American manufacturers to assemble their products in northern Mexico using cheap labor. The plan succeeded, but its main beneficiaries turned out to be women, who, it was determined, would make better workers for the new factories, or maquiladoras, because of their presumed superior manual dexterity. Word spread throughout Mexico that thousands of assembly-line jobs were cropping up in Juárez, and the nation’s north quickly became the emblem of modernity and economic opportunity. In the seventies, factory-sponsored buses rumbled into the heartland and along the coasts and returned with thousands of hungry laborers. Among them were many single women with children in tow, who, aside from landing their own jobs in the maquilas, began to staff the throngs of stores and restaurants that proliferated to satisfy the new consumerism of Juárez’s formerly cash-strapped population.

And so, if the working women of this border city had once earned reputations as prostitutes or bartenders, they now earned paychecks as factory workers, saleswomen, police officers, teachers—a few even as managers and engineers in the concrete tilt-ups that were constructed all around town to house around four hundred maquiladoras. For anywhere from $4 to $7 a day, they assembled automotive parts and electronic components and made clothing. Of the girls who couldn’t afford to go to college—which is to say, the vast majority—some took computer classes, where they learned to use Microsoft Word and Excel so that they might become secretaries and administrative assistants. Juárez, after all, is a city that places a high premium on skills such as knowing how to use computers and speak English. Even in its most impoverished desert neighborhood, a dazed collection of impromptu homes stitched together from wood pallets, mattresses, cardboard boxes, and baling wire, I saw a tiny brick shack with a dozen mismatched chairs planted outside and a hand-painted sign that promised “Clases de inglés.“

But the migration was too fast, too disorganized. The population shot up to an estimated 1.5 million. Gone was the charm Juárez had possessed in the thirties, when its valley bore succulent grapes, or in the forties, when the music of Glenn Miller and Agustín Lara never stopped playing on Juárez Avenue, even as its neighboring country went to war. It was one of Mexico’s biggest blunders to have planted its largest industrial experiment in the desert, in a city separated from the rest of the country not only symbolically, by its distinctly North American feel, but also physically, by the stunning but unforgiving Juárez Mountains. Cardboard shanties began to dot the landscape. Sewage spilled onto the streets. Power lines reproduced like parasites. Today, radio talk-show hosts ramble on about the ways in which immigrants ruined their beautiful community. I asked a well-bred young man what he felt were the virtues of his hometown, and despite a genuine effort, all he could name were the swank, cavernous clubs where the rich kids spend their weekends consuming alcohol by the bottle.

Even as the maquiladoras have begun relocating to China in the past two years, the reputation of Juárez as a city of opportunity lingers in impoverished rural Mexico. Inside the city, however, Mexico’s economic vulnerability is exposed like raw flesh. The city is filled with broken people who crack open with the most innocent of questions. I met a woman from Zacatecas who lives in Anapra with her husband and three daughters in a minuscule house that they built out of wood pallets and thatched with black roofing material. They possess one bed, no refrigerator, and a tin washtub for bathing. State officials offered them this sliver of land, but the sliver is in the desert mountains, where life is not “beautiful,” as the woman’s brother had sent word home; it’s shivery cold and always covered in a thin film of orange dirt. When I asked her how she liked living in this colonia along the city’s northwestern frontier, the woman’s smile quivered and a puddle of tears instantly dribbled to her chin.

Still, the worst part about Juárez, she told me, is the threat of violence that hangs over the sprawling city like a veil of terror. For just a short distance from her home, the bodies of girls who resemble her own sixteen-year-old Ana have appeared in the desert. Lured to their deaths—perhaps by promises of a job?—they lie abandoned like the heaps of trash that fleck this interminable sea of sand.

Disculpe, señorita . . .” I turned toward the male voice that came from behind me and saw a dark-skinned, round-faced man in his thirties striding in my direction with a large basket of candies wedged between his neck and shoulder. He was heavyset, clad in light-brown slacks, a white, long-sleeved shirt with blue pinstripes, and a green windbreaker.

It was lunchtime, and I had walked out of a restaurant to return a call to a source on my cell phone, leaving behind three journalists with whom I’d been roaming the city. Diana Washington Valdez, an El Paso Times reporter who has been chronicling the Juárez women’s deaths, had thought I should meet an attorney who is defending one of the government’s scapegoats for the murders. But when we had rattled the wrought-iron gates of his office, there had been no reply. We had decided to wait at a small restaurant next door, and since a peal of music was issuing from a nearby television, I had gone outside to return the call. After I’d finished, I’d dialed my sister’s number.

He looked rather humble, and this, I thought, was confirmed by the apologetic smile he wore, as if he were sorry to be intruding for something as mundane as the time or how to find a street. I half-smiled at him. “Hold on,” I told my sister. I was about to save him the trouble of asking by telling him that I was not from around here when he spoke once more.

“Are you looking for work?”

Journalists and activists and sociologists trying to explain the loss of hundreds of women in such violent ways have constructed a common narrative. The story tells that when the immigrants came to Juárez from the countryside, they brought with them traditional Mexican ideas about gender. Women were to stay home, obey their husbands, and raise their children. But when wives and girlfriends and daughters began earning their own paychecks, they tasted a new independence and savored it. They bought nice things for themselves. They went dancing. They decided when bad relationships needed ending. In many cases, because unemployment rates for men were higher, women even took on the role of breadwinner in their families. The men saw their masculinity challenged and lashed out. Their resentment, uncontained by weakened religious and community bonds, turned violent, into a rage that manifested itself in the ruthless killing of women. This story has become so popular that when I interviewed the director of the Juárez Association of Maquiladoras, he recited it for me almost as though he were delivering a pitch at a business convention.

Yet the violence in Juárez—against men as well as women—is at its barest a criminal act and the direct by-product of the lack of rule of law in the Mexican justice system. Killers know that the odds are overwhelming that they can get away with murder. Nationally, only two in every one hundred crimes are ever solved, including cases that are closed by throwing a scapegoat in jail. There are no jury trials, and it is easy to influence a judge with money. If not one of the Juárez girls’ cases has been properly resolved in ten years, only two explanations are possible: Law enforcement is either inept or corrupt. Most people believe both are true.

“I got to witness the inefficiency,” says Oscar Maynez, the chief of forensics in Juárez from 1999 to 2002. Maynez has been involved in the cases of the murdered women of Juárez from the beginning. In 1993, as an instructor at the state police academy, he was skimming criminal files to use in his class when something disturbing grabbed his attention: In three separate cases, it appeared that three young women had been raped and strangled. Fearing that a serial killer might be on the loose, he created a psychological profile of the killer. When he approached his superiors with the report, however, every one of them, including the Juárez police chief and the deputy attorney general in the state capital of Chihuahua, dismissed its importance.

Maynez left his job a year later to pursue a master’s degree in Washington, D.C. When he returned to reorganize the state crime lab, in 1999, he was greeted by a growing pile of women’s remains, along with case records and forensic evidence, all of it hopelessly confused. Though some of the bodies still had vital clues embedded, the lab had never done any follow-up on those that had appeared between 1993 and 1999, including DNA analyses of the rapists’ semen. Maynez was certain now—and the thought enraged him—that either a serial killer or a well-funded criminal ring was systematically targeting Juárez’s youngest and poorest women. And yet, six years after his initial findings, neither the local nor the state authorities had made an effort to pursue an investigation according to Maynez’s profile.

In early November 2001 eight female bodies were found in a cotton field across a busy street from the maquiladora association’s air-conditioned offices. Five of them had been dumped in an old sewage canal, the other three in an irrigation ditch. Most followed a similar modus operandi: hands bound, apparently raped and strangled. Two days after the first corpses were found, Maynez and his crew began their work, dusting for evidence with tiny paintbrushes. As they did so, a man drove up in a bulldozer, saying that he’d been ordered by the attorney general’s office to dig up the area to search for more bodies. Maynez sent him off to work elsewhere, preserving the crime scene.

Just a few days later, the police presented an edited videotape confession of two bus drivers who said they had killed the women, naming each of the eight. It seemed odd that the murderers would know the complete names of their victims—middle names, maternal and paternal names. When the accused were admitted to the city jail, it became obvious that they were scapegoats and had been forced to confess, for they showed multiple signs of torture, including electrical burns on their genitals. The cost of defending them turned out to be quite high. In February 2002 one of the two lawyers who was representing the drivers was shot and killed by state police officers as he drove his car; they say they mistook him for a fugitive. (An investigation was conducted, but the officers were never charged.) And a few days after the national human rights commission agreed to hear the drivers’ cases, one of them mysteriously died in custody while undergoing an unauthorized surgery based on forged documents for a hernia that he had developed from the torture.

To date, eighteen people have been arrested in connection with the murders, including an Egyptian chemist named Abdel Latif Sharif Sharif, who arrived in Juárez by way of the United States, where he had lived for 25 years. He had accumulated two convictions for sexual battery in Florida. Sharif, who has been jailed in Mexico since October 1995, was accused by Chihuahua state prosecutors of several of the Juárez murders but convicted of only one. Though the conviction was overturned in 2000, a state judge ruled in favor of the prosecution’s appeal, and Sharif remains imprisoned in Chihuahua City.

Judging from the lack of evidence, none of those eighteen individuals has been justly charged or convicted. The biggest testament to this is the fact that the murders continue unabated. At a press conference in jail in 1998, Sharif divulged information he had received from a police officer who claimed that the person behind the killings was Armando Martínez, the adopted son of a prominent Juárez bar owner. Sharif’s source, Victor Valenzuela Rivera, said that he had overheard Martínez bragging about the murders at the Safari Club, one of his father’s bars and a place frequented by police officers and narcotraficantes. Valenzuela insisted that Martínez, who also goes by Alejandro Maynez, had said he was being protected by government officials and the police and that he had bragged about his involvement in the trafficking of drugs and jewelry. The following year, Valenzuela repeated this account before several federal legislators and reporters; again, there were bloody repercussions. After Irene Blanco, the woman who had defended Sharif in court, demanded that the press investigate the allegations against Martínez, her son was shot and nearly killed by unknown assailants. The police say the shooting was drug-related; others blame police officers themselves. Martínez’s whereabouts are unknown.

Valenzuela’s testimony was not the only suggestion that the murders might be linked to the drug world. In 1996 a group of civilians searching for women’s remains in Lomas de Poleo came upon a wooden shack and inside it an eerie sight: red and white votive candles, female garments, traces of fresh blood, and a wooden panel with detailed sketches on it. On one side of the panel was a drawing of a scorpion—a symbol of the Juárez cartel—as well as depictions of three unclothed women with long hair and a fourth lying on the floor, eyes closed, looking sad. A handful of soldiers peered out from behind what looked like marijuana plants, and at the top there was an ace of spades. The other side showed similar sketches: two unclothed women with their legs spread, an ace of clubs, and a male figure that looked like a gang member in a trench coat and hat. The panel was handed over to Victoria Caraveo, a women’s activist, who turned it in to state authorities. Though the incident was reported by the Mexican papers, today government officials refuse to acknowledge that the panel ever existed.

As Oscar Maynez sees it, the problem with the Mexican justice system begins with “a complete absence of scruples among the people at the top.” The criminologist says that the state crime lab has become merely an office that signs death certificates. In the case of the eight girls’ bodies discovered in 2001, Maynez told the El Paso Times, “We were asked to plant evidence against two bus drivers who were charged with the murders.” Though the drivers were prosecuted, their evidence file, Maynez says, remained empty. Frustrated, he resigned in January 2002. Because it has become his life’s mission to save Juárez—or at least reduce its death toll—he is still intent upon getting his job back some day. The only chance of this happening is if the National Action Party (PAN) retakes control of the state.

If I was not able to escape, how much would I have to suffer before being killed? Was this it? Had I really gambled it all for a story?

But the PAN-controlled federal government isn’t doing much to solve the Juárez murders either. Some of Chihuahua’s top leaders a decade ago now sit in the highest ranks of President Vicente Fox’s administration. In December 2001 federal legislators formed a committee to investigate the issue; it has yet to release a report. The bad blood between political parties and the long history of turf wars between state and federal law enforcement groups have prevented any sort of interagency cooperation, a key to solving difficult crimes in the United States. (On one of my trips to Juárez, I watched news footage of a mob of men pummeling each other—it was the state and federal police, fighting over who was supposed to protect the governor of Chihuahua when he flew into the city.) Early this March, the federal attorney general finally sent his investigators to the border, and in May they announced their intention to reopen fourteen of the murder cases as part of an investigation into organ smuggling.

Activists in Juárez and El Paso believe that the only way the murders can ever be solved is for Mexican federal officials to invite the American FBI to investigate, but historically, neither side has seemed eager for this to occur. Nationalism runs high in Mexico, and the country’s leaders do not want Americans meddling in their affairs. In El Paso, officials like outgoing mayor Ray Caballero hesitate to offend their peers in Chihuahua. Caballero, who has had little to say publicly about the murdered women, told me, “For me to come out and make one pronouncement does not solve the problem.” Perhaps circumstances are changing. This spring his office announced the creation of a hotline that will allow people in Juárez to report information to the El Paso police, who will then turn it over to investigators in Chihuahua. In late April, two deputies of the Mexican federal attorney general asked the FBI to collaborate with them on their investigations of the Juárez murder cases and the Juárez drug cartel. FBI agents have also been training Mexican prosecutors and detectives in Juárez and El Paso.

Are you looking for work?”

My heart stopped. I knew that line, knew it immediately. My eyes, frozen, terrified, locked onto his. “N-n-n-o,” I believe I stuttered, but the man spoke again: “Where are you from?” His eyes crawled down my body and back up to my face. I was wearing leather boots, a black turtleneck, and fitted jeans—the last pair of clean pants I had managed to dig out of my suitcase that morning. And I regretted it immediately, because they might have been appropriate for trekking in mountains but not, I realized now, for walking around downtown. My heart was back, pounding furiously. Only then did I notice that as I had talked on the phone, I had absentmindedly paced half a block away from the restaurant’s door. At that moment, there was nobody within sight, not even a single officer from the police station next door. I tried to envision the scenarios, tried to imagine some chance of safety. Would he ask me to follow him somewhere? Would someone drive up out of nowhere and force me into a vehicle? Did I have control of the situation or did he? If I darted toward the restaurant door, would I startle him, causing him to reach over and grab me? If I screamed, would my sister, who was now dangling by my thigh on the other end of a cell phone—listening, I hoped desperately, to this conversation—be able to help? Would Diana and the others inside the restaurant hear me over the music? If I was not able to escape, how much would I have to suffer before being killed? Was this it? Had I really—and the brief thought of this made me sad—gambled it all for a story?

For a few infinite seconds, nothing, and everything, was possible. But as my heart began to slow down and my mind sped up, I thought of another possibility. “I’m from El Paso,” I said.

Irma Monrreal lives in a dust-tinged neighborhood known as Los Aztecas. The streets are unpaved, lined with tiny cement homes that peek out from behind clumsy cinder-block walls. Her home on Calle Grulla, which she bought on credit for $1,000, originally consisted of one room, in which she slept with seven children, but her eldest sons constructed another two rooms. Like so many immigrants in Juárez, Irma had hopped on a train and headed to the border with visions of prosperity flitting about in her head. In the fields of her state of Zacatecas, she had earned $3 a day hoeing beans and chiles. The big talk those days was of the factories in Juárez, where one could make nearly three times as much money. Since she and her husband had separated and her two eldest boys, who were thirteen and fourteen years old, would soon be needing jobs, she moved to Juárez and altered her sons’ birth certificates so that they could immediately begin work in the maquiladoras.

Though Irma had a bundle of children to care for, she was closest to her third-youngest, Esmeralda, a blithe girl with a broad, round face and an unflinchingly optimistic attitude. At fifteen, she had completed middle school and was determined to keep studying so that someday she might work in a big place—like the airport, she told her mother—and earn lots of money. She was an excellent typist. She didn’t date or spend much time with friends, but she was extremely close to her little sister Zulema, who was four years younger. The two pretended that they were television stars or models, and on special occasions they attended mass and treated themselves to lunch. When nighttime set in, they dreamed in bunk beds.

The only thing Esmeralda desired even more than an education was to have a quinceañera and to wear, like every other girl in Juárez who turns fifteen, a white gown to her rite-of-passage celebration. Her mother, who earns about $30 a week at a plastics factory, was saving up what she could to pay for the party, but Esmeralda felt the urge to pitch in. When an acquaintance asked Irma if she could borrow her teenage daughter to help around the house, Esmeralda pleaded with her hesitant mother to say yes, promising that she would work only up until the December 15 ceremony.

A week went by, and Esmeralda was excited, chatty. One evening she confided to her mom that a young man who was a few years older than she and who worked at the printshop where she had ordered her invitations had asked her out to lunch. She seemed deeply flattered that someone would notice her, but Irma admonished her not to take any offers from strangers. Her daughter promised that she wouldn’t. A second week passed. Esmeralda would finish working at about four o’clock and head straight home, arriving well before Irma departed for her overnight shift at the maquiladora.

But a few days later, something went terribly wrong. At four-thirty, there was no sign of Esmeralda. Then it was five o’clock. Then six. At ten minutes to seven, Irma was forced to leave for work, but she asked her other children to watch for their sister. In the factory, she punched her time card and began talking to God silently.

The night dragged. When her shift was finally over, at seven in the morning, Irma rushed home to see her daughter’s face, but her world imploded when her children opened the door: Esmeralda no llegó. The girl had vanished.

During the following ten days, Irma sometimes wondered whether her mind hadn’t just taken a crazy turn. Her Esmeralda. How could this be happening? At night, she was overwhelmed with terror as she speculated where the girl might be, what she might be going through at that very moment. To lose a family member and not know what has happened to her is to live an existential anguish of believing fiercely and at the same time losing all notion of truth. I spoke with a psychologist at a Juárez women’s crisis center who said that she finds it almost impossible to help the relatives of disappeared people heal because they are unable to discount that their abducted family member is either dead or alive. In El Paso I met Jaime Hervella, a Juárez native who runs a small accounting and consulting business as well as an organization for relatives of the disappeared on both sides of the border. “It’s the worst of tragedies,” he said, motioning with his waxlike hands over a cluttered desk. Then his bifocals fogged up, and he wept suddenly. “I just can’t handle talking to the little old women, the mothers. Morning comes and they implore God, the Virgin, the man who drives the dump truck. Nighttime falls and they are still asking themselves, ‘Where could my child be?’ And the hours pass in this way, and the sun begins to disappear.”

As she scavenged her memory for clues, Irma recalled the young man who had invited her daughter to lunch and immediately sent her son to look for him. But the owner of the printshop said he’d left his job. He refused to give any more information. After several visits herself, Irma finally persuaded the shop owner’s son to tell her where their former employee lived. She found the little house, but it was locked; she banged on the door, the windows, screaming loudly in case her daughter was inside, listening. Esmeralda had told her mother that the young man had asked her for her schedule and that he had wanted to know whether her mom always walked her home from work. As Irma circled the house, the man arrived. She explained who she was and asked if he knew anything about her daughter, but he brushed her away, saying that he was married.

A few days later, a co-worker at the maquiladora asked Irma if she’d heard the news: Eight bodies had been found in a couple of ditches at the intersection of Ejército Nacional and Paseo de la Victoria. Could one of them be Esmeralda? Next came the phone call from the state prosecutor’s office, asking her to identify the body. At the morgue, however, Irma was told it was too gruesome to view. She would have to obtain signed permission from the prosecutor’s office. They offered to bring out the blouse that was on the corpse when it was found; Irma’s heart collapsed when she glimpsed the speckled yellow, pink, orange, and white. It was the blouse that Esmeralda’s older sister Cecilia had sent from Colorado, where she had moved to with her husband.

Yet there was still that lingering doubt, so Irma requested the permit to see the body. Fearing the shock would be too great for their mother to bear, her two eldest sons insisted on identifying it themselves. When they arrived home from the morgue, they were silent, their heads hung low.

“So?” Irma asked anxiously. “Was it your sister?”

But the response was hesitant, brittle: “We don’t know.”

“What do you mean, you don’t know?!” Irma sputtered.

“It’s just that . . . she doesn’t have a face.”

The words shattered on the floor like a Christmas ornament. She burst: “But what about her hair—was it her hair?!”

“It’s just that she doesn’t have any hair,” came the grief-stricken reply. “She doesn’t have any ears. She doesn’t have anything.”

The corpse presumed to be Esmeralda’s was one of the three found on November 6, a day before the other five were discovered a short distance away. All of the bodies were partially or wholly unclothed, some with their hands tied. But unlike the other girls, most of whom had been reduced to mere skeletal remains, Esmeralda’s state of decomposition was particularly grisly and perplexing. She was missing most of the flesh from her collarbone up to her face. The authorities suggested that the rats in the fields had had their share, but Irma noted—and Oscar Maynez, the chief of forensics, concurred—that it would have made more sense for them to feast on the meatier parts of her body. The mystery deepened when the forensic workers took hair and blood from Esmeralda’s mother and father and sent them to a laboratory in Mexico City. Even when DNA samples from the parents who had identified clothing were compared with those from the girls wearing the clothing, the results came back without a match. This opened up two possibilities: Either the samples had been grossly contaminated or, even more eerily, the murderers were switching clothes with other, as yet unfound, victims.

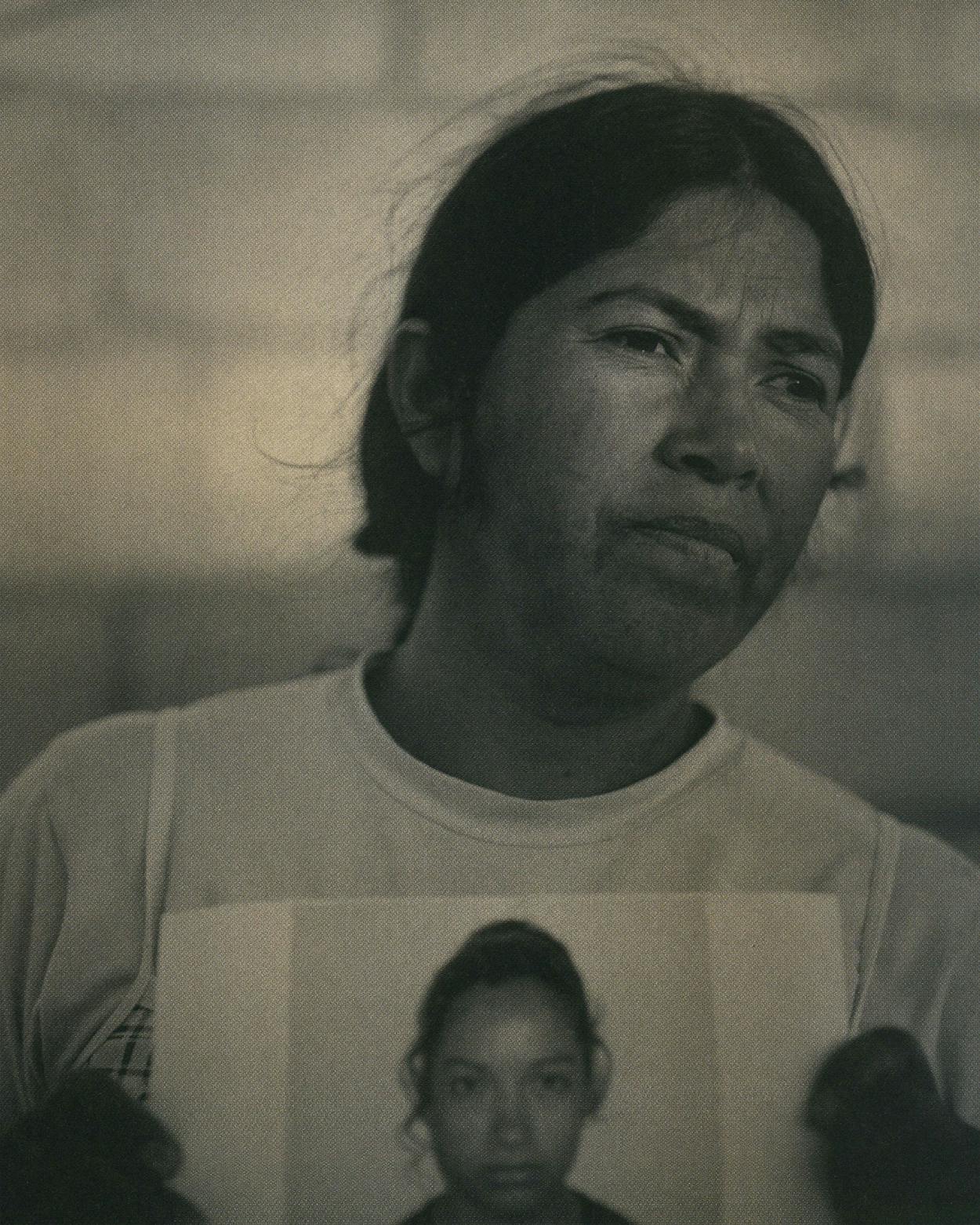

“Why?” Irma cried out as I sat with her one wintry afternoon in her tidy home, which is crammed with curly-haired dolls and deflated balloons and stuffed animals her daughter had collected—the last traces of happiness left in her little house. “Do they want to drive me crazy or something? Is it her or isn’t it?” In a silver frame on top of a brown armoire, Esmeralda sat squeezed into a strapless red top, her shoulder-length hair dyed a blondish brown. She was laughing irresistibly—cracking up—but across from the photo, Irma slumped in her chair in blue sweats and a denim shirt, her body heaving uncontrollably as I listened, speechless. “Why does God let the evil ones take the good ones away? Why the poor, if we don’t bring any harm on anybody? Nobody can imagine what this trauma is like. I go to work and I don’t know if my children are going to be safe when I return. It’s a terror that’s lived day by day, hour by hour.”

Like numerous stories I had heard from other victims’ families, Irma’s included the lament that her family has fallen apart as her children struggle to confront the tragedy of losing their sister and try to assign blame. Unable to channel their newfound hate, they have begun hating each other. Her eldest sons have stopped talking to her. Zulema, who refuses to sleep in her bunk bed now, attempted to kill herself and her eight-year-old brother with tranquilizers a doctor had prescribed for Irma. Defeated, the woman spoke with the shame of a child who has discovered that she has made an irrevocably wrong choice. She wished, with all her might, that she had never made that fateful decision to come to Juárez. “They’ve destroyed my life,” she said with vacant eyes and a flat voice, once she had regained her composure. “I don’t believe in anything anymore. There is a saying that one comes here in search of a better life, but those are nothing but illusions.”

Irma eventually claimed the body, she says, so that she would “have somewhere to cry.” Instead of determining whether more lab work needed to be done, the authorities instantly handed it over. They never interrogated the suspicious young man Irma had reported, and in a tasteless act of disregard for her daughter, they ruled that the cause of the young woman’s death was “undetermined,” even though it seemed apparent that she had been strangled. On November 16 Irma buried the corpse, using the quinceañera savings to pay for the $600 coffin.

Soy de El Paso,” I said to the man outside the restaurant. I held my breath. I remembered what Diana had told me when we first met to talk about the story: “They know who to leave alone. They leave the Americans alone. They leave the rich girls alone, because there might be trouble. The other girls? A dime a dozen.” And yes, his interest faded instantly. “I’m sorry,” he said, still bearing his apologetic smile, though somewhat more sheepishly. “I—I just saw you holding that piece of paper so I thought maybe you were looking for a job. Sorry.” He turned around and began to walk away.

I was still frightened, but now that I felt a little safer, the journalist in me began to return. “Why?” I called out nervously. “Do you know of a job?” He turned around and stared at me. “I hire girls to work at a grocery store,” he said. His eyebrows crinkled. “Where are you from?” Shaking my head, I stammered, “Oh, no—I’m from El Paso. My friends are waiting for me inside this restaurant.” I brushed past him in a hurry, skipping up the restaurant’s steps and to the table where the rest of the group was finishing their meal. Diana was gone. I took my seat. My legs, my hands, trembled violently.

“You’ll never guess what happened to me,” I said in a shaky voice. The others fell silent and looked at me with interest. “I just got offered a job.” As the words spilled, one of the group nodded slowly. “You fit the profile,” she said. When I described the man to her, she said that he had walked into the restaurant earlier, while I was on the phone. He had chatted with the woman who was cooking, taken some food, and left.

I jumped from my chair and stepped over to the counter. “Excuse me, señora,” I said to the woman at the grill. “Do you know the man who just came in a few minutes ago?” “Not very well,” she replied. “At night he guards the lawyer’s office next door and by day he sells candies on the street.”

At that moment, something blocked the light from the doorway. I turned around and found myself face to face with the same man from outside, this time without his basket. He looked nervous. “Let me buy you a Coke,” he offered. “No, thanks,” I replied firmly. Then I asked him, “Do you really have a store?”

“You’re a journalist,” he said, “aren’t you?” His question caught me by surprise. I turned toward my table, then back to his intense gaze. “I—I’m here with some journalist friends,” I stuttered. “No,” he said forcefully, “but you’re a journalist, aren’t you?” It was obvious that he knew. “Well, yes, but I’m just here accompanying my friends, who are working on a story.” His tone softened. “Come on, let’s sit down. Let me buy you a drink. En confianza.” You can trust me. “No,” I repeated, “I’m with my friends and we’re leaving.” I walked back to the table. Diana had returned, unaware of what had transpired. Later I would learn that she had gone to the lawyer’s office, encountered the candy man, and told him she was with a group of journalists who wanted to see his boss. But with the man standing there, all I wanted to do was get away. We all gathered our belongings and hurried toward the door. “The lawyer says he’ll be here tomorrow, if you want to see him,” we heard the man call out to us. I never turned back.

That night, safe in El Paso, I stared at the ceiling in the darkness of my hotel room and replayed the afternoon’s events over and over. My family had worried when I told them that I was going to write about the women of Juárez, even after I assured them that plenty of other journalists had done so safely. But you, they shot back, as if I’d missed the most obvious point, you look just like those girls. I thought of how much care I had taken not to go to Juárez alone, even if it had meant sacrificing my journalistic independence. And yet, in that one brief instant I had let my guard down, and I had been approached by someone mysterious. I will never know for sure if that was it—if, as I have told colleagues I felt at that moment, I really touched the story, my own life colliding with those of the girls whose lives I had been hoping to preserve. What I do know is this: that I had felt my heart beat, the way they must have felt it beat too.

As I thought this, warm tears spilled down the sides of my face and trickled into my ears. And I realized that I was crying not for myself, but for the women of Juárez—for the girls who had died and for the mothers who survived them. They say that whenever a new body is found, every grieving mother relives her pain. I was crying for the girls who had stayed on the other side of the border. For the ones who couldn’t leave their reflections on paper and run far, far away, as I was going to do. I cried because I realized how easy it would have been to believe the man who approached me; because I understood that the girls were not naive, or careless, or as a former attorney general of Chihuahua once said, asking for it. They were simply women—poor women, brown women. Fighters, dreamers. And they weren’t even dreaming of all that much, by our standards: a secretarial job, a bedroom set, a fifteenth-birthday party. A little chance to live.

I cried because of the absurdity of it all, because it was possible for a life to be worth less than a brief taste of power. I cried thinking of how we had failed them.