The Gulf of Mexico’s coral reefs are in hot water—quite literally. A new study from researchers at Rice University, the University of Texas at Austin, and Louisiana State University found that as sea-surface temperatures rise because of climate change, and as waters turn more acidic by absorbing more carbon dioxide, coastal reefs could collapse in the coming years.

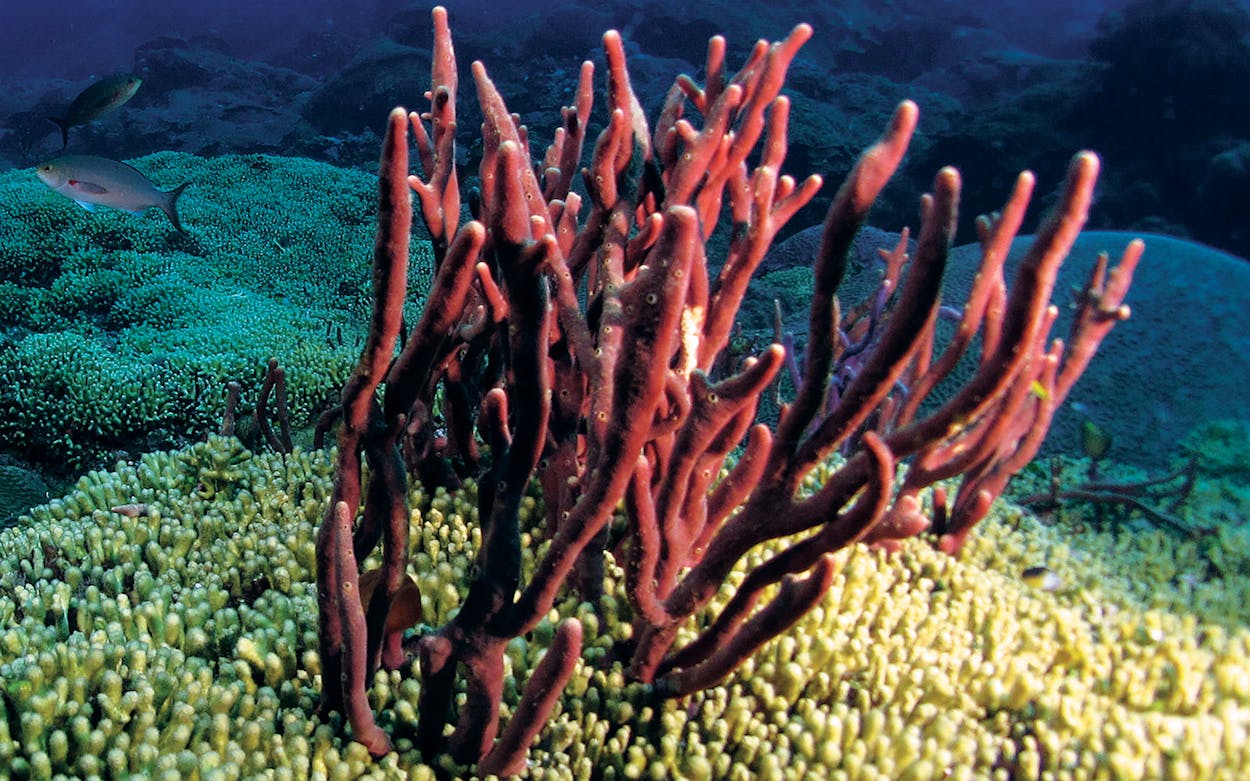

The shallow-water reefs in the Gulf, like Texas’s Flower Garden Banks reefs about a hundred miles offshore from the Texas-Louisiana border, support a complex ecosystem of marine life. Divers can witness schools of butterfly fish and eels darting between coral and sea sponges that bloom in shades of orange, yellow, and purple. Comb jellies drift overhead, as do creatures like sharks, stingrays, and sea turtles.

But corals are extremely sensitive creatures. If the water is too warm or too cold, if there’s too much sunlight filtering through, or if there is an excess of nutrients in the water, they begin to die. First, they expel the algae that live in their tissues and sustain them. Then they turn white, a phenomenon known as bleaching. Soon after, the reef can’t support the surrounding marine life.

The Gulf’s reefs have been shrinking rapidly for decades. Most of them are in “poor or fair condition” today, according to the study, which was published in Frontiers in Marine Science. But the added stress of climate change could prove catastrophic, triggering a series of negative events. For example, as the Gulf waters warm, stronger hurricanes form. Those winds can cause upwelling, bringing colder water and a harmful concentration of nutrients into the reefs. And as the coral die off, the coast loses an important natural barrier that can help protect shorelines—and thousands of coastal residents—from flooding, storm surges and erosion.

“We could solve some of the anthropogenic problems right now,” said Sylvia Dee, the study’s lead author and a professor and climate scientist at Rice University. When it comes to runoff and oil spills, better environmental regulation and enforcement could go a long way. But in terms of climate change, “there’s some level that we are already committed to,” she said. “Even if we dramatically reduced carbon emissions today, it’s like a train with no brakes.”

The study suggests that carbon dioxide levels would have to stabilize at 2005 levels in order to “avoid widespread degradation.” In November of this year, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere hovered at about 410 parts per million. In 2005, that number was just shy of 380. Greenhouse gases can persist in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, heating up the planet as long as they’re present. Short of a miracle, or some feat of geoengineering, it’s a pretty bleak picture for coral reefs around the world.

There’s some evidence that coral reefs have survived in increasingly hot and acidic waters before. Hundreds of millions of years ago, the climate resembled the future we’re facing. Although major reefs across the oceans collapsed, some species proved resilient. But corals, like most organisms alive today, adapt and evolve over centuries, if not millennia.

The rate of climate change today, and its effects on rising sea temperatures, is happening drastically faster than at any other point in Earth’s history. Making matters worse for coral, migration isn’t a viable survival strategy. While animals—and even some plants, whose seeds are transported by those animals, or the elements—can attempt to find greener and cooler pastures, coral reefs are held captive in an increasingly hostile marine environment.

“Humans are leading the way for this species destruction,” Dee says. “You can visit these beautiful [marine sanctuaries like Flower Garden Banks] today, but that might not be an option for people in a hundred years.”

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly stated that fishing isn’t allowed in the Flower Garden Banks sanctuary. In fact, fishing by traditional hook and line is permitted. The story has been updated.